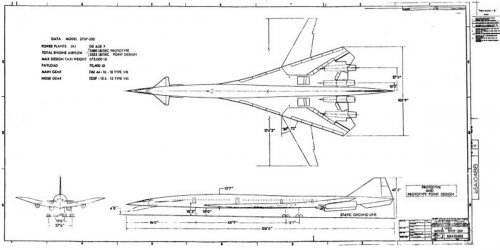

More specifically, the 2707-dash-nothing original swing-wing/no canards version.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

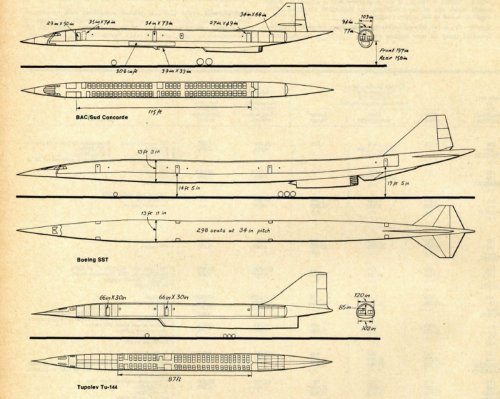

US Supersonic Transport (SST) Program 1960-1971

- Thread starter Orionblamblam

- Start date

- Joined

- 3 June 2006

- Messages

- 3,094

- Reaction score

- 3,954

That enthusiasm for speed was first reflected in Life magazine. Even before the XS-1 flew, Life had gotten wind of the NACA’s impending assault on the sound barrier and asked Langley’s aerodynamicists what a supersonic airliner of the future might look like. John Stack got a group together to lay out a commercial supersonic aircraft using 1947 state-of-the-art technology. The design they produced for the magazine, pictured in figure 1.1, featured R. T. Jones’s swept wings on a bullet-shaped, X-1–like body. A large turbojet engine in the tail provided power for takeoff and landing, but turbojets were not powerful enough to pierce the sound barrier so the group added rocket engines in detachable pods that would drop away once the aircraft was supersonic. Above Mach 1.2, ramjets in the wing roots took over and powered the plane. But the design had a range of only 1,500 miles, permitting it to fly the famed New York to Havana casino run but not much else. And it could carry only ten passengers, hardly enough to provide economical operation.

[Attachment]

The design was the beginning, however, of an effort that aeronautical engineers both at the NACA’s labs and in the aircraft manufacturers’ design groups returned to repeatedly during the next decade. While supersonic transportation was at best a distant dream in 1947, it represented an obvious future outcome of the quest for higher speeds and altitudes, and as engineers developed new knowledge about supersonic flight, they revisited the SST issue to see how much closer to the dream they had come. The next assessment of the state of SST art was published five years later, following a concerted attempt by the NACA, the Air Force, and the Navy to produce jet-powered aircraft capable of supersonic speeds.

Source: High-Speed Dreams: NASA and the Technopolitics of Supersonic Transportation, 1945-1999, By Erik Conway, 2005

Hi folks,

I know, this concept is before the 1960's, but I couldn't find a suitable topic.

Dear mods, please feel free to edit or move this post to another topic.

- Joined

- 26 May 2006

- Messages

- 34,873

- Reaction score

- 15,734

Great find my dear Rolf,

and I knew from while,my dear Scott wanted any info about it;

http://up-ship.com/blog/?p=16898

and I knew from while,my dear Scott wanted any info about it;

http://up-ship.com/blog/?p=16898

blackkite

Don't laugh, don't cry, don't even curse, but.....

- Joined

- 31 May 2007

- Messages

- 8,819

- Reaction score

- 7,692

B2707-300 Mockup in Hiller museum. Now in Boeing Seattle.(Under the restration?)

Attachments

Apteryx

ACCESS: Confidential

- Joined

- 28 September 2007

- Messages

- 157

- Reaction score

- 48

The Boing SST mockup has has nine lives!

I visited the Kissimmee museum, of which it was the centerpiece, back in 1980. It was pretty impressive, featuring a good deal of cutaway structure. The museum's owner had also rounded up a Convair Sea Dart and a B-25, but the balance of the "exhibits" were basically salvaged junk. I had the exhibit hall to myself.

I visited the Kissimmee museum, of which it was the centerpiece, back in 1980. It was pretty impressive, featuring a good deal of cutaway structure. The museum's owner had also rounded up a Convair Sea Dart and a B-25, but the balance of the "exhibits" were basically salvaged junk. I had the exhibit hall to myself.

- Joined

- 31 May 2009

- Messages

- 1,154

- Reaction score

- 671

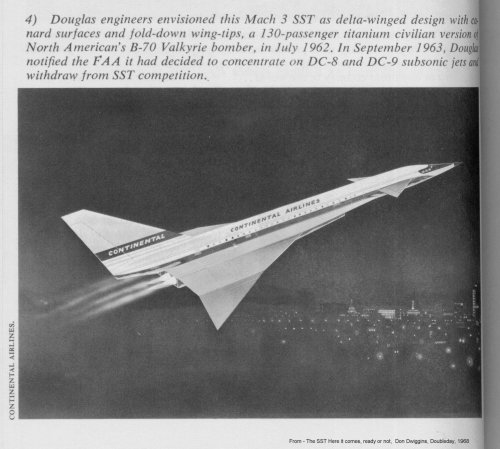

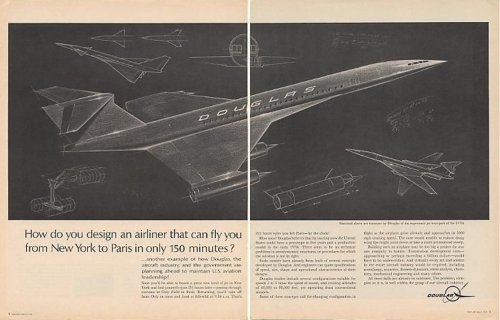

Douglas Model 2229 SST factory model. This airplane was designed in co-operation with North American Aviation / Los Angeles Division. Note similarities to WS-110A (XB-70): fold-down wingtips for compression lift, canards, grouped engine (4-pack) with variable intake ramps and retractable high-speed windshield, among others.

(Photos by Chad Slattery)

(Photos by Chad Slattery)

Attachments

Forty pages in, & finally here it is..

View: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s1jrIbXTnak

& it has to have got more air-time than any of the FAA projects..

& it has to have got more air-time than any of the FAA projects..

blackkite

Don't laugh, don't cry, don't even curse, but.....

- Joined

- 31 May 2007

- Messages

- 8,819

- Reaction score

- 7,692

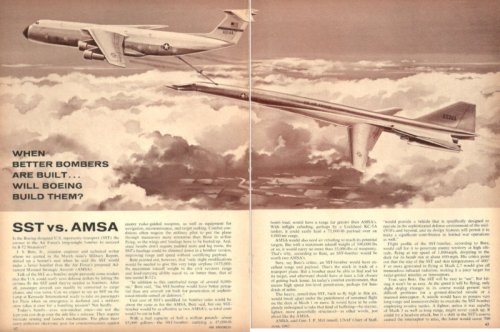

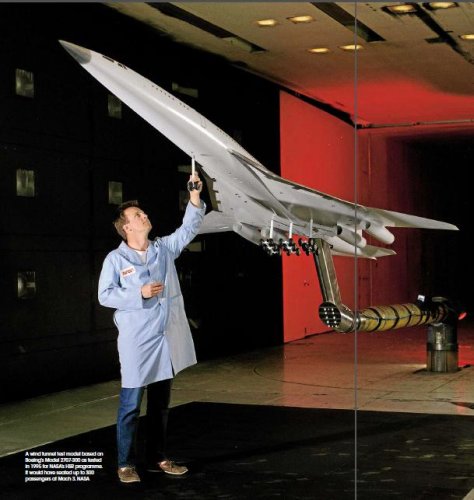

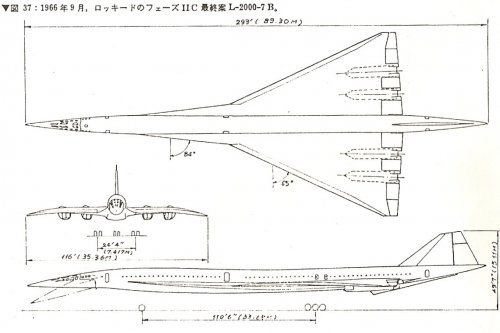

Hi my dear hesham. I tried to read this picture's text.

"A wind tunnel test model based on Boeing's Model 2707-300 as tested in 1995 for NASA's HSR program. It would have scaled up to 300 passengers of Mach3. NASA."

I feel that this model had a double delta wing. Little different from B2707-300's wing.

"A wind tunnel test model based on Boeing's Model 2707-300 as tested in 1995 for NASA's HSR program. It would have scaled up to 300 passengers of Mach3. NASA."

I feel that this model had a double delta wing. Little different from B2707-300's wing.

Attachments

- Joined

- 25 June 2009

- Messages

- 14,749

- Reaction score

- 6,114

For some reason I hadn't been on this topic for the past six months and there are some real treasures here, especially the Douglas 2229!

Thanks a lot to blackkite for all the efforts.

I have my doubts about the veracity of that Convair SST in military guise. Looks like a not-very-well-made PS job to me.

Thanks a lot to blackkite for all the efforts.

Orionblamblam said:circle-5 said:I don't think that last image was SST material.

Actually, it was. I have the Convair diagrams of the thing around here, somewhere. That's the first time I've seen that done up in USAF duds... the same painting is usually shown sans military logos.

I have my doubts about the veracity of that Convair SST in military guise. Looks like a not-very-well-made PS job to me.

archipeppe

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 18 October 2007

- Messages

- 2,431

- Reaction score

- 3,149

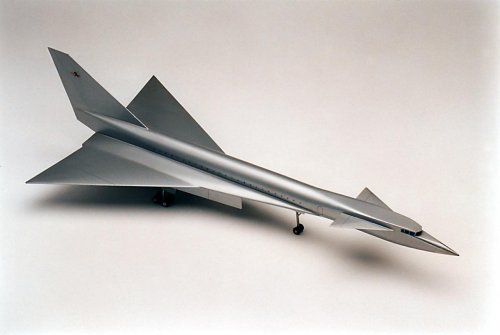

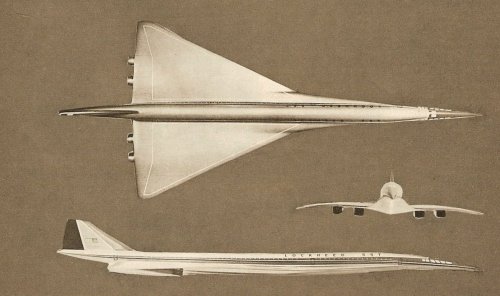

Douglas or Tupolev??

blackkite

Don't laugh, don't cry, don't even curse, but.....

- Joined

- 31 May 2007

- Messages

- 8,819

- Reaction score

- 7,692

Tupolev!!??archipeppe said:Douglas or Tupolev??

MaxLegroom

Why not?

- Joined

- 28 December 2013

- Messages

- 161

- Reaction score

- 49

Considering the similarities of the middle picture to the Tu-22 bomber, that could have been a design Tupolev was considering for their SST. The artwork itself also seems different from the style used in American proposals...

- Joined

- 26 May 2006

- Messages

- 34,873

- Reaction score

- 15,734

MaxLegroom said:Considering the similarities of the middle picture to the Tu-22 bomber, that could have been a design Tupolev was considering for their SST. The artwork itself also seems different from the style used in American proposals...

That's right Max.

archipeppe

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 18 October 2007

- Messages

- 2,431

- Reaction score

- 3,149

hesham said:MaxLegroom said:Considering the similarities of the middle picture to the Tu-22 bomber, that could have been a design Tupolev was considering for their SST. The artwork itself also seems different from the style used in American proposals...

That's right Max.

I agree, indeed the nose of all three aircrafts has a strong resemblance with Lockheed L-2000's one....

- Joined

- 25 June 2009

- Messages

- 14,749

- Reaction score

- 6,114

blackkite said:The body of U.S. SST is full of beauty without an equal.

A matter of taste, as usual. I personally think it looks weird and twisted. I prefer the Lockheed and NAA projects, not to mention of course the Tupolev and Concorde!

blackkite

Don't laugh, don't cry, don't even curse, but.....

- Joined

- 31 May 2007

- Messages

- 8,819

- Reaction score

- 7,692

blackkite

Don't laugh, don't cry, don't even curse, but.....

- Joined

- 31 May 2007

- Messages

- 8,819

- Reaction score

- 7,692

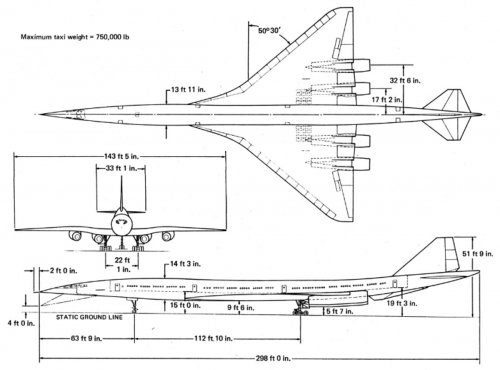

Or is not found so.

It is a bold design.

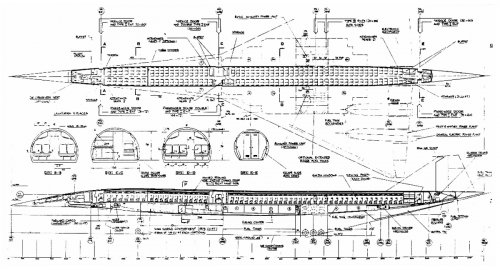

B2707-300 had horizontal tail stabilizer which required long tail.

The caudal portion would be bounded in order to secure the ground clearance at the time of taking off and landing.

It is a bold design.

B2707-300 had horizontal tail stabilizer which required long tail.

The caudal portion would be bounded in order to secure the ground clearance at the time of taking off and landing.

- Joined

- 25 June 2009

- Messages

- 14,749

- Reaction score

- 6,114

archipeppe said:Douglas or Tupolev??

With regards to your question, which may or may not have been asked in joke, here is a 1963 ad and an article which both clearly show the designs to be Douglas...

Attachments

MaxLegroom

Why not?

- Joined

- 28 December 2013

- Messages

- 161

- Reaction score

- 49

I agree, in a way, in that the top was clearly a McDonnell-Douglas proposal, and the bottom clearly Douglas designs, but the middle one looked like little relation to the others, and even the style of the artwork was very different from what was often used for American design proposals.

As for the SST designs, I'm beginning to wonder if we didn't throw away the best chance of success with the NAC60 design being eliminated at the end of phase I. While I'd have to research this design further, which I am beginning to do, it would be hilarious for this to have been the case.

As for the SST designs, I'm beginning to wonder if we didn't throw away the best chance of success with the NAC60 design being eliminated at the end of phase I. While I'd have to research this design further, which I am beginning to do, it would be hilarious for this to have been the case.

blackkite

Don't laugh, don't cry, don't even curse, but.....

- Joined

- 31 May 2007

- Messages

- 8,819

- Reaction score

- 7,692

Thanks for rare model! Perhaps North American could became a good SST maker, because they already established how to design mach 3 super cruising big aircraft at the day. I imagine that it's very hard to design mach 3 cruising aircraft even now.

- Joined

- 4 July 2010

- Messages

- 2,514

- Reaction score

- 3,090

That is one sexy SSTcircle-5 said:North American Aviation Model NAC-60 factory presentation model.

djfawcett

With Enough Power, Anything Will Fly

- Joined

- 16 December 2012

- Messages

- 274

- Reaction score

- 422

I believe the best chance of the US having a SST was with Lockheed. If Boeing initial concept was the 2707-300,

and were selected, there is a good bet the aircraft would have been built. The NAA NAC-60, if selected, also had a reasonable

chance of being built. The idea that the technology existed to develop a swing-wing design of that size was just plain wrong.

and were selected, there is a good bet the aircraft would have been built. The NAA NAC-60, if selected, also had a reasonable

chance of being built. The idea that the technology existed to develop a swing-wing design of that size was just plain wrong.

'Plain wrong'?

Why? - What is wrong with the idea, Barnes-Wallis had plenty of good ideas, including this..

If you mean that the technology of the day wasn't up to it, do check F-111 & B-1.

& note also - the Mach 3 capable XB-70 also featured large movable flying surfaces..

Why? - What is wrong with the idea, Barnes-Wallis had plenty of good ideas, including this..

If you mean that the technology of the day wasn't up to it, do check F-111 & B-1.

& note also - the Mach 3 capable XB-70 also featured large movable flying surfaces..

blackkite

Don't laugh, don't cry, don't even curse, but.....

- Joined

- 31 May 2007

- Messages

- 8,819

- Reaction score

- 7,692

Hi!

You should say that a design of the Boeing 2707-200 is bad rather than a swing-wing is bad.

It is a mistake to have installed the engine in the horizontal stabilizer.

By this thing, the weight of the horizontal stabilizer increased and the weight increment became remarkable conjointly with adoption of the swing-wing.

When engines installed to the main wing, some portion of wing root bending moment due to lift is cancelled by the weight of engines.

But when engines installed to the horizontal tail stabilizer, this merit disappeared. And the distance between center of gravity and horizontal stabilizer is shortened and trim drag become large. And longitudinal moment of inertia become large, low speed controlability is poor and card is needed.

You should say that a design of the Boeing 2707-200 is bad rather than a swing-wing is bad.

It is a mistake to have installed the engine in the horizontal stabilizer.

By this thing, the weight of the horizontal stabilizer increased and the weight increment became remarkable conjointly with adoption of the swing-wing.

When engines installed to the main wing, some portion of wing root bending moment due to lift is cancelled by the weight of engines.

But when engines installed to the horizontal tail stabilizer, this merit disappeared. And the distance between center of gravity and horizontal stabilizer is shortened and trim drag become large. And longitudinal moment of inertia become large, low speed controlability is poor and card is needed.

djfawcett

With Enough Power, Anything Will Fly

- Joined

- 16 December 2012

- Messages

- 274

- Reaction score

- 422

Actually, I should have elaborated further. If you notice, I said a swing-wing on that size aircraft. Both of the aircraft referenced by JAW are

far smaller than the 2707-200. The material technology simply did not exist at that point in history to keep the pivot structure of the size required

light. Bottom line, Boeing and NASA rolls the dice and lost.

As far as engine placement, unless the engines are outboard of the pivot point on the wing, there is little gain in loading from their mass.

Not commonly known, one of the primary reasons for the addition of the canard on the -200 was to reduce the fuselage bending moment.

The aircraft's length had grown to the point that the fuselage started to become rediculously heavy.

far smaller than the 2707-200. The material technology simply did not exist at that point in history to keep the pivot structure of the size required

light. Bottom line, Boeing and NASA rolls the dice and lost.

As far as engine placement, unless the engines are outboard of the pivot point on the wing, there is little gain in loading from their mass.

Not commonly known, one of the primary reasons for the addition of the canard on the -200 was to reduce the fuselage bending moment.

The aircraft's length had grown to the point that the fuselage started to become rediculously heavy.

blackkite

Don't laugh, don't cry, don't even curse, but.....

- Joined

- 31 May 2007

- Messages

- 8,819

- Reaction score

- 7,692

Thanks. Following explanation for SST engine installation is my misunderstanding. I imagined subsonic transport engine and wing.

When engines installed to the main wing, some portion of wing root bending moment due to lift is cancelled by the weight of engines.

But when engines installed to the horizontal tail stabilizer, this merit disappeared.

When engines installed to the main wing, some portion of wing root bending moment due to lift is cancelled by the weight of engines.

But when engines installed to the horizontal tail stabilizer, this merit disappeared.

blackkite

Don't laugh, don't cry, don't even curse, but.....

- Joined

- 31 May 2007

- Messages

- 8,819

- Reaction score

- 7,692

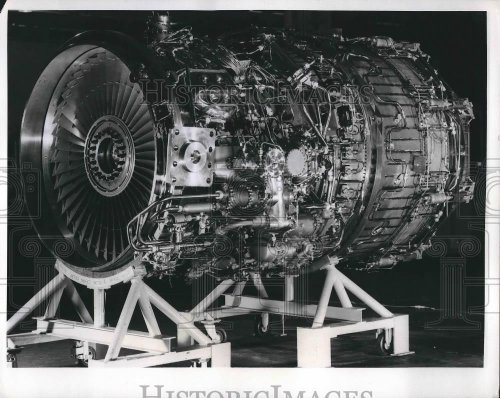

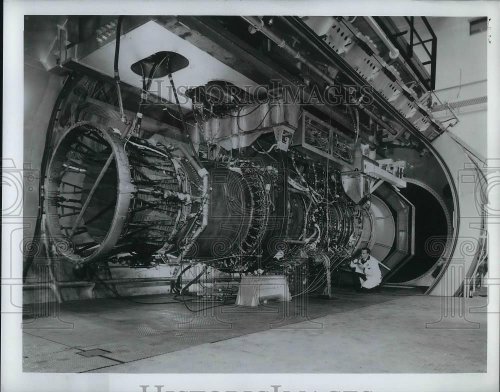

Hi!

Attachments

-

P&W JTF17.jpg141.6 KB · Views: 188

P&W JTF17.jpg141.6 KB · Views: 188 -

GE4 J5.jpg134 KB · Views: 213

GE4 J5.jpg134 KB · Views: 213 -

L2000 cabin mockup.jpg157.2 KB · Views: 798

L2000 cabin mockup.jpg157.2 KB · Views: 798 -

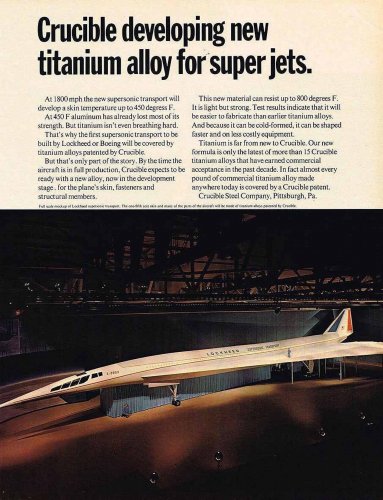

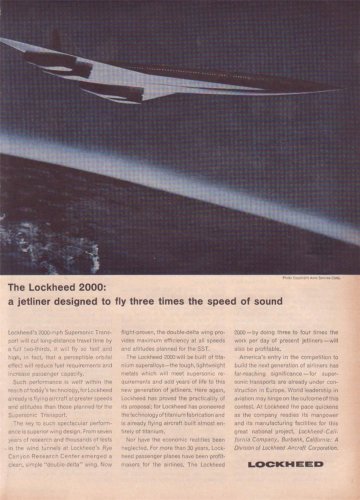

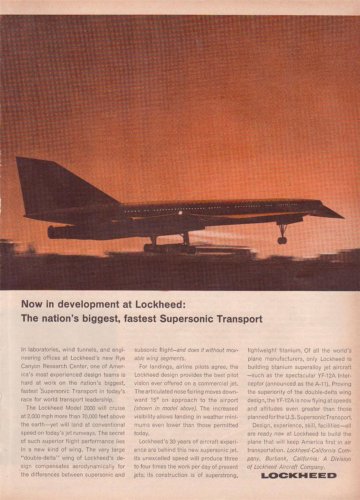

Lockheed sst pamphlet 4.jpg450.2 KB · Views: 875

Lockheed sst pamphlet 4.jpg450.2 KB · Views: 875 -

Lockheed sst pamphlet 3.jpg521.8 KB · Views: 937

Lockheed sst pamphlet 3.jpg521.8 KB · Views: 937 -

Lockheed pamphlet 2.jpg386 KB · Views: 1,015

Lockheed pamphlet 2.jpg386 KB · Views: 1,015 -

L2000 pamphlet.jpg455.4 KB · Views: 1,090

L2000 pamphlet.jpg455.4 KB · Views: 1,090

Merv_P

ACCESS: Confidential

- Joined

- 29 July 2006

- Messages

- 115

- Reaction score

- 17

blackkite said:

Another mid-60s concept, similar to the fifth picture down, via "2001". I know there's only so many ways to configure a flight-cabin but the influences from that period are clear.

Attachments

Similar threads

-

FLIGHTS OF FANTASY: The Lockheed L-2000 SST in airline service

- Started by Sentinel Chicken

- Replies: 9

-

Could the US have built an SST?

- Started by uk 75

- Replies: 35

-

-

-