HERZLIYA, Israel — To convince Israel and its supporters in Congress that the White House truly “has its back” with respect to threats posed by Iran, US President Barack Obama and top Cabinet officials have repeatedly flagged the fact that Israel is the exclusive regional recipient of the F-35, America’s premier stealth strike fighter.

“Indeed, Israel is the only nation in the Middle East to which the United States has sold this fifth-generation aircraft,” Obama wrote in a letter last month to Rep. Jerold Nadler, a New York democrat representing the largest Jewish district in the country.

Some military and political leaders in Israel are pushing to make that regional exclusivity permanent.

Earlier this month, seeking to sway support in Congress for the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) with Iran, Secretary of State John Kerry used nearly identical language as Obama.

In a Sept. 2 letter to lawmakers, Kerry cited F-35s to Israel as a key manifestation of the administration’s commitment to preserve Israel’s so-called qualitative military edge (QME) against regional foes.

“Israel’s first F-35 aircraft will be delivered in 2016, making it the only country in the region with a US fifth-generation fighter aircraft,” Kerry wrote.

And at an Israeli Independence Day celebration last May, Vice President Joe Biden told hundreds gathered at the Israeli Embassy in Washington to thunderous applause: “Next year, we’ll deliver to Israel the F-35, our finest, making Israel the only country in the Middle East with a fifth-generation aircraft. No other.”

Now, as pressure mounts on Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to jettison his battle with the White House and accept the president’s offer to fortify Israel’s QME well into the future, experts here and in Washington are urging him to put Obama to the test.

Beyond billions of dollars in additional grant aid and a menu of military modernization needs, experts here said Netanyahu should squeeze out definitive assurances that Israel will remain the exclusive regional operator of the F-35 for years to come.

How long?

“Forever,” quipped retired Maj. Gen. Amos Gilad, the Israeli Defense Ministry’s longtime director of policy and political-military affairs who leads QME-related talks with the Pentagon and State Department.

In a Sept. 7 exchange following a conference address here, Gilad refused to say whether a Mideast moratorium on F-35 exports will be an agenda item in bilateral talks on bolstering Israel’s QME. “They said officially that they won’t sell to anybody [in the region] but Israel,” Gilad told Defense News.

But when pressed for how long Israel expects those commitments to remain in place, Gilad said, “It’s all pertaining to negotiations, and it’s all very complicated. I can’t comment on this subject.”

US Sen. Tom Cotton, junior Republican senator from Arkansas, was similarly cagey when asked during a visit here earlier this month about Israel’s interest in indefinite exclusivity to the F-35.

“I don’t want to discuss specifics, but obviously Israel’s QME depends on what it has when compared against what neighboring countries have. There’s been a lot of talk from this administration about preserving Israel’s edge. But talk is cheap, especially when it comes to the Middle East.”

He added, “I and most members of Congress are 100 percent committed to action — not talk — that will maintain and improve Israel’s QME.”

Amos Yadlin, a retired Israel Air Force major general who directs the Tel Aviv-based Institute for National Security Studies, is a prominent voice in favor of immediate re-engagement with Washington to mitigate political, strategic and operative risks inherent in the nuclear deal with Iran.

“Obviously one of the ways we can work bilaterally to bolster QME and manage risks of the JCPOA is to preserve Israel’s exclusive status with regard to F-35,” Yadlin told Defense News.

That said, he noted that Washington’s allies in the Arabian Gulf also require and deserve US security assurances as a result of the nuclear deal with Iran.

“Balancing the need to preserve and reinforce our QME while, at the same time, answering legitimate concerns of the [Gulf Cooperation Council] will be something of a fine art,” Yadlin said. “Very careful thought and coordination will be required as we move forward.”

When asked about Israel’s interest in maintaining a regional monopoly on the F-35, an Israel Air Force project manager — one of the first pilots selected to fly the fifth-generation fighter — said those types of discussions were well above his pay grade.

“I don’t know what is or isn’t a subject of discussion at the political level. All I can say is I believe the US will not give for the foreseeable future this airplane to countries that can be a problem to Israel.

“If they do, the consequences will be that we won’t have an edge,” the IAF officer said.

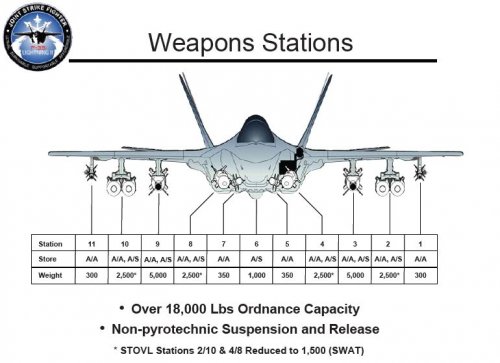

In a recent briefing in Washington, F-35 program executives from Lockheed Martin, prime contractor for the stealth strike fighter, said the program has tremendous growth potential. Much like the Lockheed Martin F-16 program, which has produced more than 4,000 jets in four decades, executives projected a similar worldwide market for F-35s in the coming 40 years.

“Last year was the 40th anniversary of the F-16. … There’s no reason to believe that the F-35, 40 years from now, we won't be talking about a program of more than 4,000,” said Steve Over, Lockheed Martin director for F-35 International Business Development.

That said, Over insisted that the firm did not yet have licenses to market F-35s among GCC countries. “We’re definitely not out there marketing F-35s indiscriminately throughout the world,” he said.

“This is a national security issue of the highest order,” said Mike Howe, the company’s F-35 director for Israel and Europe. “We will not get ahead of our government in any way with respect to future sales to other countries.”

Eyal Ben-Reuven, a retired Israeli Army major general and lawmaker from Israel’s opposition Zionist Union party, said the Knesset’s Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee to which he belongs is not yet privy to details of the security enhancements Israel plans to secure from Washington. But he said an Israeli request to maintain a long-term Mideast monopoly on the F-35 seemed “highly prudent and reasonable,” given the instability and unpredictability of the region.

“In the last five years, all the intelligence sources, methods and means have completely failed to anticipate the ramifications of the Arab Spring. Not us, not the Americans, nobody predicted what happened in Syria, Libya, Yemen. So today, Saudi Arabia seems stable, but tomorrow, who knows?” Ben-Reuven said.

Efraim Inbar, a professor of Bar Ilan University and veteran Mideast security specialist, said he was doubtful if Washington would be willing or able to commit to a long-term Mideast moratorium on F-35 exports. Citing “enormous political and economic pressure to come” by the US defense industry and its traditional Mideast customer nations, Inbar warned that F-35 sales in this region could trigger the next big battle between a future US administration and Israel.

“The US government managed to sell F-15s to Saudi Arabia despite tremendous pressure from Israel and our friends on Capitol Hill. What’s to say it will be any different with F-35?” Inbar said.

A former Israeli defense official noted that Saudi Arabia was approved to receive its first F-15s in 1978, less than three years after the Israel Air Force. With F-16s, the gap between Israel and Egypt — its Camp David peace partner — was less than two years, while Jordan was authorized for F-16s in 1996, a year after it signed a peace treaty with Israel.

“If we want a sense of what’s in store for us, it’s worthwhile looking back at the F-16 program. It took less than 10 years for it to go to Bahrain and UAE, then it spread to Oman, Morocco and now they’re flying it in Iraq. Who’s next, Lebanon?”

The former official declined to be quoted by name, as he occasionally advises Israel’s MoD on matters of strategic cooperation with Washington.