The Marine Corps triumphantly declared its variant of the F-35 combat ready in late July. In the public relations build-up, the recent demonstration of its performance on the USS Wasp was heralded as a rebuttal to the program’s critics. But a complete copy of a recent memo from the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation (DOT&E)—obtained by the Project On Government Oversight through the Freedom of Information Act—reveals that a number of maintenance and reliability problems “are likely to present significant near-term challenges for the Marine Corps.”

The Marine Corps named this demonstration “Operational Test One,” but it turns out it wasn’t actually an operational test, “in either a formal or an informal sense of the term.” To count as an operational test, conditions should closely match realistic combat conditions. But DOT&E found the demonstration “did not—and could not—demonstrate that Block 2B F-35B is operationally effective or suitable for use in any type of limited combat operation, or that it was ready for real-world operational deployments, given the way the event was structured.”

The details buried inside the report’s annexes also show just how much trouble the crew faced in attempting to keep the F-35s selected for the demonstration flightworthy. Before the demonstration even began the Marine Corps had to swap out one F-35B with another “due to a fuel system fault that would have been impractical to fix at sea given the maintenance workload.” In combat, not only would this kind of replacement be impractical, it would likely be impossible.

Unrealistic Tests

To further explain how the demonstration was not a realistic operational test, DOT&E offered a laundry list of other artificial advantages present in the demonstration:

A relatively empty flight deck, without over 20 additional aircraft that make up the rest of the Air Combat Element (ACE). DOT&E notes that there are “additional complications that the presence of the other aircraft and personnel from the ACE would inject into the F-35B operations and maintenance.&rdquo

The absence of key combat mission systems, since they were either not installed or not cleared for use. Specifically, the nose apertures for the infrared Distributed Aperture System, which provides missile launch warning and situational awareness to pilots, were not installed. Night vision camera use was restricted to elevations above 5,000 feet. And only limited radar modes were available for some of the Block 2B aircraft. Critical warfighting systems like these cannot operate without advanced software which was unavailable at the time of the demonstration. These systems will not be fully integrated into operational aircraft until the block 3F software is ready in 2017 at the earliest. If these systems had been available, they would likely have added additional maintenance burdens.

For the software that was installed, DOT&E noted that degradations that would have to be addressed in combat “were often ignored during this event, as long as the aircraft were able to safely conduct the event’s limited training objectives.” This meant that in some instances, planes were flown when they were not fully combat ready.

The aircraft were not cleared to carry any ordnance. This was hardly surprising, in part because the F-35B will not be able to fire its gun until 2019.

“Significant assistance from embarked contractor personnel” on maintenance support. Lockheed Martin, Pratt & Whitney, and Rolls Royce all provided Field Service Engineers (FSE). These personnel were embarked aboard the USS Wasp along with the uniformed maintainers. The number of individuals varied from day to day, but the report notes there were approximately 80 contractor civilians participating during the test. Such personnel would likely not be available during actual combat operations.

Due to an unreliable logistics management system—named the Automatic Logistics Global Sustainment (ALGS) system—crew used “[n]on-operationally representative [supply system] workarounds” to support the program, including for basic tasks such as fueling. The Marine Corps was able to support the aircraft only with “several ad hoc supply actions to obtain spare parts…that could not have been accomplished in a timely or a practical manner when operationally deployed.” This includes staging several extraordinary parts runs using MV-22 aircraft specially staged for the purpose. Even with all of these advantages, DOT&E found “it was difficult for the Marines to keep more than two to three of the six embarked jets in a flyable status on any given day.” In combat conditions, DOT&E wrote, it only gets “substantially tougher” for the aircraft to deploy.

Poor Test Results

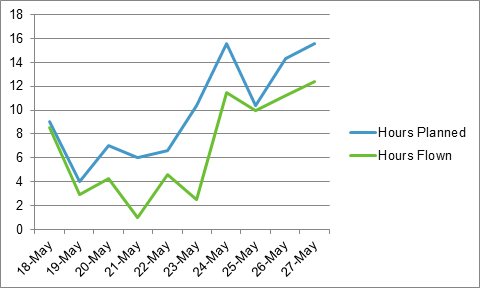

The F-35Bs used for the demonstration were never able to achieve the planned number of flight hours over the 10 days of flight operations due to various maintenance issues. The report compares planned flight hours and hours actually flown for each day of flight operations; hours flown were only 70 percent of those scheduled. Here is how the planes performed, as detailed in Annex B of the report:

Monday, May 18 – Hours flown: 8.5; Hours planned: 9.0

Tuesday, May 19 – Hours flown: 2.9; Hours planned: 4.0

Wednesday, May 20 – Hours flown: 4.3; Hours planned: 7.0

Thursday, May 21 – Hours flown: 1.0; Hours planned: 6.0

Friday, May 22 – Hours flown: 4.6; Hours planned: 6.6

Saturday, May 23 – Hours flown: 2.5; Hours planned: 10.4

Sunday, May 24 – Hours flown: 11.5; Hours planned: 15.6

Monday, May 25 – Hours flown: 10.0; Hours planned: 10.4

Tuesday, May 26 – Hours flown: 11.2; Hours planned: 14.3

Wednesday, May 27 – Hours flown: 12.4; Hours planned: 15.6

DOT&E Flight Operations Chronology chart

Data from DOT&E "Annex B — Flight Operations Chronology"

Maintainers aboard the ship had their hands full during the test. One aircraft lost a “turkey feather” retaining pin in the engine when the plane first landed aboard the ship. This rendered the aircraft Not Mission Capable (NMC), an acronym which is repeated over and over again in the report.

The appendices obtained by POGO also show that maintenance problems grounded the planes throughout the demonstration. As examples of the problems encountered, at the conclusion of flight operations on May 20, three of six aircraft were down for maintenance. Four of six aircraft were out of action on the evening of May 22. On Saturday, May 23, the squadron commander cancelled two planned missions to give maintenance crews more time to complete aircraft repairs.

The report shows the unusual lengths used to resolve some of the issues. For example, one plane needed a replacement fuel boost pump. None were available on board, so one was flown in from Norfolk Naval Air Station on an MV-22 Osprey. Maintainers attempted to install the replacement part, but they found it had been damaged at some point either before or during shipping. Three more identical parts were later shipped to ensure at least one undamaged part would be available.

In another example, one of the F-35B’s needed a replacement voltage regulator to return to mission capable status. The part was unavailable locally, so one was flown from Fort Worth, Texas, out to the USS Wasp within 18 hours. The authors of the report noted, “This level of support should not be expected as normal for combat deployments once away from the continental United States.”

Extraordinary measures like these were only feasible for this test because it was conducted a relatively short distance off the east coast of the United States—a luxury DOT&E found unlikely to be available to commanders in combat: “The use of helicopter and MV-22 aircraft to fly maintenance equipment from ship to shore to support the maintenance of divert aircraft will not always be available in a timely manner during real-world operational deployments.”

The Marine Corps and Lockheed Martin anticipated issues of this sort and made special arrangements to support this event. The report notes the Marine Corps placed several MV-22’s on standby to conduct logistics runs for the test. Further, Lockheed Martin had prioritized support for the deployment “very highly.” It positioned contractors at various bases across the country to rapidly move needed parts through the system. This is hardly surprising, since it was in Lockheed Martin’s interests to do everything possible to see that this demonstration went as smoothly as possible.

Support crews had to resort to other extraordinary measures to keep the planes flying and to meet timeline expectations. The F-35 has often been described as a “flying computer.” The plane’s computers generate massive amounts of logistics data, which needs to be transferred off the planes and transmitted back to their home stations. Crews on the ground found the Autonomic Logistics Operating Unit could not handle the 400 to 800 megabyte data downloads quickly enough to meet the timeline. For purposes of comparison, that’s 3 to 6.5 hours of YouTube videos. After trying to transfer the files through several military computer networks both aboard ship and at military facilities ashore technicians finally resorted to driving off base and using commercial Wi-Fi. They had to burn the data to CDs, and then manually upload it to the Wasp squadron operating units to move the necessary files. Once those files were uploaded, they found “numerous errors” including missing files and inconsistencies between home station and deployed files that had to be corrected remotely by Lockheed Martin database administrators in Orlando and Fort Worth.

The report points out that there were also a number of other issues that arose over the course of the demonstration that were not included as potential maintenance work orders, including radio, radar, and Electro-Optical Targeting System (EOTS). Maintenance crews “made no attempt to fix these during this detachment.”

While there is nothing unusual about military equipment requiring maintenance to remain operational, the number of mechanical and electronic maintenance problems during this short period of time, and on such a highly publicized event, is remarkable. A readiness rate of 80 percent for a squadron of 6 aircraft is needed to meet combat needs according to Michael Gilmore, Director of Operational Testing & Evaluation. During this demonstration, the F-35 struggled to maintain even a 50 percent readiness level.

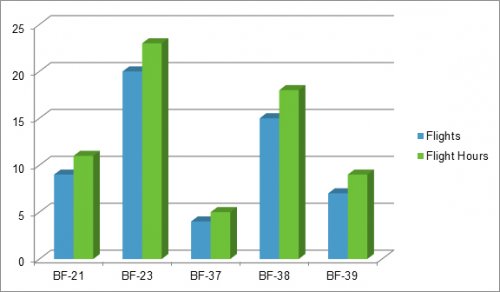

DOT&E noted that the reliability of the aircraft used in the demonstration varied widely. One plane in particular, BF-37 seemed useful only to test the skills of the embarked maintainers. It flew only one actual mission during the test, and even that brief flight required an emergency diversion to Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point. In fact, only two of the planes, BF-23 and BF-38, could be relied upon to remain airworthy. The majority of the demonstration’s flights were made by this pair. The reliability of the 5 planes used throughout the entire 11 days of the demonstration are illustrated in the chart below.

DOT&E Annex D – Daily Flight Activity

Data from DOT&E "Annex D – Daily Flight Activity"

The reliability and operational availability of an aircraft is important in terms of combat readiness and for training purposes. Even the best aircraft in the world is useless without a skilled pilot. The only way to develop better pilots is to have them fly as often as possible in conditions replicating those they will face in combat as possible. The USS Wasp operational test, which seems no more than a PR exercise, simply confirmed that beyond the highly publicized questions regarding the F-35’s combat effectiveness, more pressing issues remain about its basic reliability. If the most expensive weapons system in history can’t even get off the ground often enough to train pilots adequately, then all the money spent on it has been wasted.

Despite this poor showing, the Marine Corps still declared its variant of the F-35 ready for combat in July. It’s worth keeping in mind the major combat capabilities missing from the F-35B’s just-declared IOC. The Marine Corps’ statements to the press note that the early operational F-35Bs do not have the new night-vision helmet, the Small Diameter Bomb II, GAU-22/A four-barrel 25mm Gatling gun essential for even minimal close support of ground troops, or the ability to stream video and simultaneously fuse sensor data from four aircraft. As we’ve written before, Block 2B was supposed to be the first block to have any claimed combat capability, but even this capability was not ready for the F-35s in the IOC test due to deficiencies identified in testing that cannot be resolved until later blocks. Now the first system to have “Full Operational Capability” (FOC) will be Block 4, currently scheduled to be declared fully capable in 2022—assuming no further schedule slips in the intervening seven years.

Traditionally, declaring IOC has depended upon completing combat-realistic testing, as was the criteria for the F-22’s IOC declaration in 2005. The Marine Corps admits the “initial” deployments are several years down the road. F-35Bs will not be deployed to Okinawa until 2017 at the earliest, and won’t be deployed on amphibious assault ships until 2018. It’s clear that the F-35B’s IOC declaration does not establish that any necessary combat capabilities have actually been achieved. It simply establishes that the Joint Strike Fighter Program Office and the Marine Corps were doggedly determined to reap the public relations benefits of meeting their artificial IOC deadline—even if in name only—no matter what.