Jack Northrop founded what is now the Northrop-Grumman Corporation, after several false starts, in August 1939. Northrop was the preeminent aerodynamicist of his time, and the greatest intuitive aerodynamicist that ever lived. He had designed the wings for such aircraft as the Lockheed Vega and Douglas DC-3. His main intent in starting his own company was to put into production the ultimate, aerodynamically most efficient aircraft of all - the flying wing. This work culminated in the B-35 flying wing of 1945, and its jet-powered conversion, the B-49.

The B-35 was in a competition with the B-36 to provide the Air Force with an intercontinental-range bomber. From a technical point of view, there was no comparison between the two aircraft. The B-35 was three times more aerodynamically efficient. For the same mission (a 10,000 pound atomic bomb to a 10,000 mile range) the B-35 was 2/3 the size. But Northrop was a tiny company, with its only production experience being wartime production of the P-61 Black Widow. This was a night fighter, based on the Lockheed P-38 twin-boom layout, but with Northrop aerodynamics. It was produced in very limited numbers. Stuart Symington, the powerful head of the Senate Armed Services committee, called Northrop into his office. The B-35 would go into production, he said, but only if Northrop would license the design to Consolidated Vultee for production. Convair had a mile-long government-owned plant in Dallas, Texas, that needed to be filled with work now that the war was over and B-24 production terminated.

Northrop said he couldn't do that to his staff. He returned to California, and ordered the B-35 drawings destroyed and tooling spiked. He retired, believing his flyng wing dream to be over, in 1952.

The B-49 proved that the flying wing design could be equipped with jet engines and be even more aerodynamically successful. If the B-35/B-49 had gone ahead, the US government would still be flying them today, and entire generations of B-36, B-47, B-52, and B-1 bomber aircraft would have been unnecessary.

Instead, in 1980, after a forty-year meander, the US government once again returned to the ultimate aircraft. For stealth reasons the design had to be fitted with a jagged trailing edge. But to make sure the point was not lost, Northrop engineers made sure the B-2 had the same wingspan, to the inch, as the B-35. Permission was obtained to show Jack Northrop the then highly secret B-2 just before he died.

Meanwhile, under the direction of an ex-Rand Corporation whiz kid, T V Jones, Northrop carved a modest place for itself in the military aircraft market. It developed the F-5 lightweight fighter for a US Army close air support requirement. The Army's 'Jeep Carrier' concept never went ahead, but the US Air Force bought over a thousand of the T-38 trainer version. Seemingly indestructible, they are expected to continue into service into the mid-21st Century. The F-5A and F-5E fighter versions of the aircraft went into production for the export and military aid market. This kept Northrop afloat in the 1960's and made export fighter aircraft its main business area.

Northrop Corporation again faced off against its nemesis, now part of General Dynamics, in the early 1970's. Northrop had spent years identifying the optimum lightweight export fighter, taking into account the requirements of users in the Benelux countries, Spain, Australia, and Canada. The Northrop P-530 would have two engines, like the F-5A and F-5E, but greater range and weapons capability.

Then the Air Force, smarting from having to fly oversized F-4E fighter bombers against cheap lightweight MiG-21's over Viet Nam, announced a requirement for a lightweight fighter. Northrop modified its P-530 design and was selected, together with General Dynamics, to build a prototype of the design for a fly-off. The Northrop YF-17 was superior to the General Dynamics YF-16 in almost every way, but that same mile-long plant in Dallas needed to be fed. After the B-36, the Texas Congressional delegation had kept the plant filled with a succession of disastrous medium bomber designs - the B-58, then the F-111. After that experience, the Air Force turned to North American for its B-1 bomber. General Dynamics had no experience with combat fighters, having last built delta-winged F-106 interceptors in the 1950's. Nevertheless they won the Lightweight Fighter competition - the deal of the century, it was called - and with it, the NATO orders for the Benelux countries.

As part of the Deal of the Century, General Dynamics was to have received orders for a carrier-launched version of the fighter for the US Navy. But the Navy had other ideas. Instead it ordered the Lightweight Fighter competitors to team with traditional naval fighter vendors and propose navalized versions of the F-16 and F-17. General Dynamics teamed with Texas-based Vought, and Northrop was forced into bed with McDonnell-Douglas (McAir). Northrop management would not make the same mistake that Jack Northrop made, resulting in the B-35 never going into production. They swallowed their pride and let McAir take over lead production and design responsibility for the Northrop design. A fateful agreement was drawn up. If the McAir/Northrop team won the contract, McAir would build 60% of the airframe (by cost) and Northrop 40%. However, for any sales of the 'land based version' of the aircraft, the percentages would be reversed. Northrop would make 60%, and McAir 40%.

In the end, the Texas delegation and Pentagon supporters of commonality could not get the US Navy to accept the F-16 design. The McAir/Northrop design had the dual engines, which the Navy liked for safer overwater operations, and was superior aerodynamically. The F-16, designed for landing on long Air Force concrete runways, could simply not be slowed down enough to meet the Navy's carrier landing speed requirement. The F-17, derived from the Northrop short-field export design, easily met the low landing speed and precise controllability requirements of the Navy. So McAir got the contract, and the F-18 was born.

But problems developed in Northrop's sales for the land-based version. This was actually going to be a substantially different aircraft form the Navy's F-18. It would have a different airframe, lightened by removing the provisions for landing on carriers. The landing gear would be different and lighter for the same reason. A whole different range of avionics, suitable for export, would be fitted. Northrop had a launch customer for the aircraft - the Shah of Iran. He was willing to pay the billion-dollar nonrecurring cost to develop the design. The way would then be clear for sales to Spain, Australia, and Canada. These were the countries for which the P-530 had been designed in the first place, big countries needing a fighter with dual engines and long range.

But the Shah of Iran was overthrown in the 1979, killing off the F-18L's chance of being developed. In the end, the basic Navy F-18 version was sold to the P-530's main target customers - Canada, Spain, and Australia.

But there was still a truly awesome perceived market for a lightweight fighter foreseen at the beginning of the last decade of the cold war. As part of the competitive struggle between the Soviet Union and the United States, and as a necessary prestige object in the new post-colonial developing world, vast numbers of fighter aircraft had been delivered in the 1960's. Furthermore, America learned the same lesson in Vietnam that they had learned in Korea - that their high-tech heavyweight fighters were vulnerable to lower-tech, shorter-range, but higher-performance air defense interceptors built by the Soviet Union. In the post-Korean world this lesson resulted in the F-104 and F-5, which were not taken up by the US Air Force but instead exported in vast numbers to US allies and developing countries on concessionary terms. The equivalent Soviet aircraft was the MiG-21. There were thousands of these in service, and they would need replacing in the last two decades of the twentieth century.

While the P-530/F-17/F-18 family was Northrop's prime candidate for future export business, Northrop had also been looking at improvements to the F-5E fighter. As early as 1975 a single-engined version of the F-5 using the F-18's F404 engine was studied. This could be part of an F404-engined 'high/low' F-18L/F-5X fighter mix similar to the USAF F-15/F-16 mix using the J100 engine. Others within Northrop wanted any improved F-5E to retain the traditional twin-engined layout, using two Garrett business jet engines equipped with an afterburner.

By the late 1970's Taiwan was embroiled in a series of difficult discussions with the United States about its future aircraft requirements. In the past the United States had fully supported Taiwan, but after the reapproachment with China by Nixon subsequent US administrations played a delicate balancing act of supporting Taiwan's defence needs while somehow minimizing offense to China. Taiwan had rejected an Israeli offer of Kfir C-2 aircraft for the Taiwanese fighter requirement, even though the US had given Israel clearance to sell the aircraft with the American General Electric J79 engine. But Taiwan had an absolute need to be able to fire all-weather radar-guided AIM-7 air-to-air missiles. So instead it wanted American F-4 aircraft, or eventually F-16 or F-18L fighters. None of these were acceptable to the US State Department, which saw even an early model F-4 as detrimental to negotiations with the People's Republic of China.

This led the US Department of Defense to ask Northrop to look at adapting the F-5E, already produced under license in Taiwan, to carry the AIM-7. But the basic F-5E equipped with the AIM-7, and with a radar similar to that used on the F-16A, suffered such performance degradation that the Taiwanese were not interested in it. Since Northrop was already looking at different engine combinations for a higher performance F-5X, the Department of Defense asked the company to select an airframe/powerplant combination that could accommodate the Sparrow. The F404 single-engine solution was found to be the most efficient alternative and was selected by Northrop chief designer Welko Gasich in June 1978.

Northrop CEO, T V Jones, had been a wunderkind from Stanford who had extensive contacts with the California elite. Jones lived in Bel Air, with enough acreage to grow grapes (producing one of the world's most exclusive vintages). The corporate headquarters was in one of the towers in Century City, with loft offices, and decked out with enough Islamic and modern art to look like a wing of the LA County Art Museum. Jones had paid his dues to the California Republican Party, taking the fall when it was discovered he had handed over $40,000 cash to Nixon aide Maurice Stans for use as hush money for the Watergate burglars. Jones was somewhat inconvenienced, having to step down a while as CEO, but was back at the helm at the time Carter was in power, busy wheeling and dealing again.

The Carter administration was desperate to build public support for its SALT-II strategic weapons treaty, which was in serious trouble with Senate Republicans. They solicited support from the aerospace industry, and Jones dutifully provided it., even though it meant getting into bed with Alan Cranston, liberal California Senator and long-time bane of the aerospace industry. Evidently in exchange, Carter pronounced an export fighter policy that curtailed the export potential of the F-16, and favored the F-5G.

The Carter administration ruled that, outside of NATO, Japan, and Australia, the United States would only export aircraft that were 'modifications of an existing aircraft' and 'not as good as US front-line aircraft'. This ruled out export of the new General Dynamics F-16 lightweight fighter to what was its planned main market. Furthermore, any such export aircraft had to be developed with the company's own money, not taxpayer funds. Under the Carter administration, the F-20 (then called the F-5G - a 'modification' of the existing F-5E) fell into this category because it was better than an F-5E (not a US front-line fighter) and was therefore presumed not to be as good as the F-16. Carter had cleared sale of the F-5G to Taiwan in principle, and Northrop began development using its own funds on that basis.

In response to Carter's directive General Dynamics produced a crippled version of the F-16, the F-16/79, for export outside NATO. This was the basic F-16, but equipped with a J79 turbojet rather than the more modern F100 turbofan of the basic F-16. This reduced the aircraft's climb, turning performance, and range. But the F-16/79 retained most of the F-16's avionics suite, which was after all what made the aircraft most potent. It really shows the lack of understanding within the Carter administration of modern technology that an aircraft with a moderately inferior acceleration, but the same avionics, would be considered 'crippled'. And of course General Dynamics made sure that the F-16/79 could be quickly converted to use the F100 'at a future date' (wink-wink - e.g. as soon as this silly Carter administration was out of office). But still, a fighter equipped with a single engine of the same type that earned the F-104G the name 'Widow Maker' found little interest among the air forces of the world.

When Reagan entered office, it would seem that the glory days had come for Northrop. Holmes Tuttle and the rest of Reagan's southern California kitchen cabinet from his Sacramento governor days held major influence in the new administration. The promise seemed fulfilled when Northrop landed the immense but deep-black contract for the B-2 stealth bomber. To be developed in complete secrecy, 100 of these bombers, invisible to radar, were to be built. They would bring the Soviet defense establishment to its knees by making its entire air defense system - the expensive crown jewel of the Soviet defense forces - totally obsolete.

Soviet air defense was based on an enormous web of radars, which led Soviet interceptors and surface-to-air missiles to intercepts with incoming American bombers. The B-2 was not invisible, but its radar signature was so small that it had to be within a few miles of a Soviet radar station to be detected. It could avoid known stations. Using radar detectors which could determine the direction of Soviet radars long before they could see the aircraft, it could also avoid mobile or unmapped stations. The B-2 was the cornerstone in Reagan's strategy to destroy the Soviet Union by making its offensive and defensive forces obsolete.

The B-2 was also important to Norcrafters because it was to mark the final triumph of John Northrop, the company's founder. Northrop's B-35 flying wing would finally go into production, thirty years later, in the guise of the B-2. It was not coincidence that the wingspan of the two aircraft was identical.

So it would seem that Northrop's golden days lay ahead. But Washington is not run by dictators. Other political forces were pulling in other directions. In January 1982, under pressure from China, Reagan personally vetoed the Taiwan deal for the F-5G. The aircraft had lost its launch customer. But the administration still backed Carter's export policy half-heartedly at first. The F-20 was proposed as more 'appropriate' and 'cost effective' for countries like Jordan, Egypt, and Turkey.

But General Dynamics saw the opportunity to finally be clear of Carter's goody-two-shoes edict restricting export of the F-16 to developing countries. The US Air Force began actively undermining the marketing of the F-20 through the back door. The Air Force had a vested interest in getting the F-16 widely exported and sold in massive numbers. More foreign customers for the F-16 would increase the production rate, take the aircraft down the learning curve, and make the aircraft much cheaper for the US Air Force to purchase for its own needs. Furthermore, widespread use of the aircraft by nominal allies around the world gave the Air Force a kind of reserve worldwide F-16 logistics network. Allies' ground equipment and handling facilities could be used for supporting quickly-deployed American aircraft in an emergency.

The Air Force exploited its position as a government entity to easily market the F-16. Under arcane American weapons export laws, Northrop had to submit every scrap of marketing literature, even glossy brochures that only contained information that had already been published worldwide in Aviation Week, Flight International, or Jane's, to a lengthy US government review. It could take months before approval was granted, on a case-by-case basis, to provide technical information on the F-20 to prospective customers. Air Force officers, on the other hand, could and did just hand over requested F-16 technical information to interested countries immediately, without any government approvals.

It also seemed to these countries, regardless of the technical and logistics merits of the two aircraft, that those being offered the F-20 were being told they were second-class allies, not deserving to fly the fighter that was the choice of the US Air Force. When the Reagan administration agreed to supply the Air Force version of the F-16 to Venezuela for delivery in 1983, it was the death knell for the F-20.

Reagan had also boosted F-16 production to astronomic levels as part of his defense buildup. This drove the aircraft down the learning curve and brought the price down to $ 8 million per aircraft, the same as the F-20. The F-20 now only had an advantage in technical excellence, and a logistics and fuel cost 1/3 less than the F-16. But the same gush of funds was allowing the Air Force to begin development of the F-16C. This version would be fitted out with all-digital avionics (although not a laser INS at first). It would be available by the late 1980's, and have the full backing of the US Air Force. So that would remove the technical lead of the F-20. All that was left was the logistics cost argument. Northrop attempted to address this by guaranteeing the price per flight hour to prospective customers - for twenty years (this drama is detailed below).

Another stab in the back was the decision to let Israel use foreign aid funds from the Camp David agreement to pay for development of the Lavi, a lightweight fighter that was a direct competitor to the F-20. Northrop already saw Israel's hand behind the effort to stop the sale to Taiwan and have the Taiwanese buy Israeli Kfir fighters instead. It was illogical and galling that Northrop, an American company, would be told it had to invest its own funds in development of a fighter export aircraft, while at the same time Israel would be given US taxpayer funds to develop a competitor. The logic eventually was apparent even to the US Congress, and in the end, after the F-20 was dead, the Lavi was canceled as well.

But the morass of Chinese politics led to another contradiction. Northrop began receiving calls from its contractors in 1982 that the US government had secretly contracted with General Dynamics to develop a fighter for Taiwan in replacement for the prohibited Northrop F-20! And they were going to use the avionics developed for the F-20 by Northrop and it subcontractors in the new aircraft. Imagining Northrop's vast clout in Washington, they demanded that something be done. The sense of utter betrayal ran deep through the F-20 project staff and vendor community.

The Reagan administration had publicly prohibited Northrop from selling a fighter developed with its own funds to Taiwan, then secretly arranged for Northrop's competitor to develop a replacement. The fighter being developed by General Dynamics for the Taiwanese used F-16 aerodynamics (a belly inlet), but instead of a single F404, the twin Garrett turbofans-with-afterburner engine layout that many within Northrop had originally favored for the F-20. General Dynamics had selected the F-20's General Electric radar, Honeywell laser inertial gyro system, the Bendix displays for the Taiwanese fighter.

The triptych was perfect when, in the 1990's, the US government secretly allowed mainland China to develop Israel's Lavi design as the F-10. Perhaps there was a secret agreement all along to let each side - China and Taiwan - secretly develop a fighter based on Western technology?

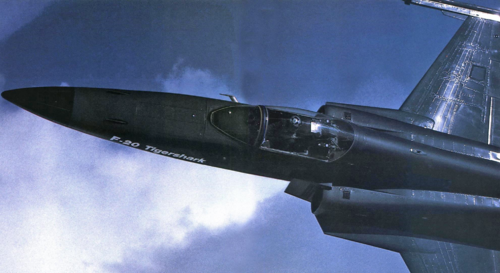

Northrop doggedly continued in its attempts to sell the fighter despite these mutliple setbacks. GG1001, the first 'engine change only' F-5G aircraft, began flight test in August 1982. In November 1982, with Carter's 'modification of an existing aircraft' fiction no longer required, the USAF agreed to redesignate the aircraft the F-20. Bahrain signed on as the first customer the same month. GG1001 demonstrated outstanding reliability. By the end of April 1983 it had logged 240 flights, including evaluation flights by 15 pilots from 10 potential customer nations. In August 1983 GI1001, the second F-20 and the first with the new digital avionics, joined GG1001 in flight test. It proved equally stable and reliable. Only a month later it flew twelve simulated air-to-air sorties in one day at Edwards Air Force Base, demonstrating both reliability and surge capability.

Through 1983 and 1984, with the aircraft flying and proving itself, sales prospects looked up. South Korea was exploring production in Korea of the F-20 as part of comprehensive development of its aerospace industry under its F-X program. Northrop made an unsolicited proposal to Saudi Arabia for 150 aircraft. The US Navy was looking for a new agressor aircraft to simulate Soviet MiG-29's. GI1001 made a 2308 mile unrefuelled transcontinental flight in December 1983 in a demonstration of its range capability. A month later GG1001 and GI1001 had completed 500 test flights, and they were joined in May 1984 by GI1002, a second all-up avionics aircraft. The high point came at the Farnborough Air Show in September 1984, when the amazing maneuverability demonstrated by the F-20 in its flying display made it the hit of the show. GG1001 and GI1001 flew on from Britain on a round-the-world tour of prospective customers.

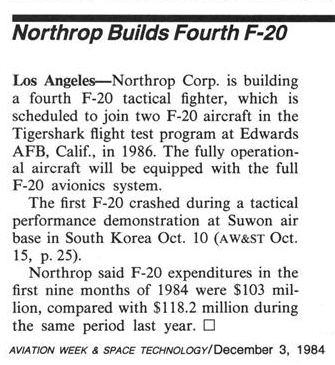

Then the tide turned against the aircraft. GG1001 crashed in South Korea on October 10, killing Northrop pilot Darrell Cornell. In January 1985 the Navy picked the F-16 rather than the F-20 for the aggressor role. General Dynamics had been able to make a price offer far below Northrop by having the Navy's F-16's engines and avionics supplied from existing government inventory, so the Navy only had to buy the airframes.

An investigation of the Korean crash cleared the F-20 of any mechanical or design fault. It was found that Cornell had blacked out due to excessive G's pulled in the acrobatic demonstration routine. During 1985 talks with Korea intensified and proposals became more detailed. By this time the production version of the F-20 being offered had many upgrades to the original configurations flying - improved radar, increased fuel, more powerful engine, new mission computer, electromechanical flaps, jet fuel starter, on-board oxygen generation - the list went on and on. The changes were made to ensure that the F-20 could now beat the F-16C in each and every performance category, while still being cheaper to buy and own.

But these changes all required an indefinite extension of the Northrop-funded aircraft development and test program. It was clear it would be some time before Seoul would be ready to sign a deal. T V Jones attempted to force the issue politically by making an unsolicited proposal in April 1985 to equip the Air Force with 396 F-20's at a guaranteed acquisition and maintenance cost well below the F-16.

After various political permuations, this was transormed into a competition between the F-16 and the F-20 for what the Air Force dubbed its 'Air Defence Fighter' requirement. This was to be versions of the aircraft equipped with AIM-7 and AMRAAM radar-guided missiles that would have to intercept and shoot down Soviet bombers in case of an attack on the United States. The F-20 had already demonstrated a successful shoot-down of a drone using an AIM-7 in February 1985 - a capability the F-16 did not possess.

Meanwhile GI1001 crashed in May 1985 at Goose Bay, Labrador, killing Northrop test pilot Dave Barnes. Barnes had been practicing his acrobatic routine at a stop on the way to the Paris Air Show. The cause was again eventually found to be pilot black-out due to the intense maneuvers, but the accident cast a pall on the struggling program. The remaining GI1002 aircraft made an appearance at the Dayton Air Show in July, and by May 1986 completed the 1500th flight of an F-20 aircraft. Northrop selected systems subcontractors and began construction of GI1003, which would be the first aircraft to include all of the new features promised to the Air Force and South Korea. A cost proposal for 120 aircraft was made to South Korea in April 1986 and the Air Defence Proposal was made to the Air Force for 180 aircraft.

On 31 October 1986, Halloween, the Air Force informed Northrop that the F-16C was selected for the Air Defence Requirement. But on the same day Northop was informed that it had been selected to design and build a prototype of the F-23 Advanced Tactical Fighter (Lockheed was selected to build a prototype of their competing F-22 design). The next day Northrop announced it was halting active development of the F-20, although it would continue to market the aircraft.

Did Northrop's highest management secretly agree to sacrifice the F-20 as part of a deal to get the B-2, the Have Blue, the TR-2, Tacit Rainbow, and a welter of other high-tech stealth programs in the 1980's? Was it sacrificed in order to get the F-23 development? The reality of any such deals are lost to history now.

After the decision was made to terminate development of the F-20, measures were taken to ensure the program could be resurrected. There was still hope of selling the entire drawing package and tooling to a foreign country, which could then complete development of the aircraft with Northrop assistance. In the months after the termination, all the paperwork associated with the F-20 was carefully stored, and the administrators and engineers documented where they had left off so the work could be resumed. The unfinished GI1003 aircraft, the flightworthy GI1002, the numerous fabricated and purchased components and systems of other aircraft, the tooling and test equipment, were all put in air conditioned storage.

The head of F-20 avionics subcontracts and a cost accountant toured the country for six months, negotiating termination settlements with Northrop's vendors and co-developers. As part of these settlements, Northrop would receive royalties on future sales of that portion of the vendor's equipment it had developed at its own expense.

The first and most likely launch customer was still South Korea. "This deal has been cleared all the way through the Blue House", the Korean equivalent of the White House, assured a new set of Northrop marketeers. Indeed, it developed later that Northrop had paid millions of dollars in bribes to South Korean officials to ensure the F-20 would be resurrected in Korea. But the deal never developed. The officials were removed from power, and the bribes were uncovered. Northrop not only did not sell the aircraft but ended up paying substantial fines and being publicly disgraced.

Another potential customer was India. India had always been held at arm's length by the US government, but the F-20 was a good alternative to India's indigenous Light Combat Aircraft development. It had been proposed to India as early as 1984. In late 1991, after rejecting an offer from the Americans to transfer F-5E tooling and production to India, the F-20 was considered again. Northrop offered to transfer GI1002, GI1003, the tooling, drawings, and know-how to India. But the talks got nowhere, and were finally abandoned (details). Last ditch talks with Pakistan and other countries also led nowhere. Northrop shortly thereafter gave up marketing the aircraft. The tooling and work in progress were destroyed, GI1002 was handed over to the California Museum of Science and Technology for display, where it remains to this day.

By then the Berlin wall had come down and the Cold War ended. The international advanced weapons market that it had fueled collapsed utterly. Used F-16's and MiG-29's became available for very little money . Export of fighter aircraft stalled completely. Old fighter aircraft were replaced at a ratio of only one new aircraft for every three older ones. The number of active combat aircraft in the world declined from 37,600 in 1990 to under 27,400 by 2005. The number of fighter aircraft declined from 23,400 to 17,200. In the face of the availability of inexpensive, modern fighter aircraft surplus to the Cold War powers, the demand for new aircraft virtually evaporated. So perhaps it was actually a stroke of luck for Northrop that the F-20 did not go through after all.

Northrop itself, in the defense consolidation of the 1990's, positioned itself as a high-tech weapons integrator and abandoned the aircraft design and export market. It acquired Grumman, and paradoxically some of its 'enemy' subcontractors on the F-20, such as Westinghouse. By 2005 it was the third largest defense contractor, having survived with its own name at the top of the masthead while its larger competitors had passed into history. Arch-rivals General Dynamics, McDonnell-Douglas, Grumman, Vought, Fairchild, Martin, and North American Rockwell - all were absorbed into the big three of Boeing, Lockheed, and Northrop. If the F-20 was a stalking horse to divert the competition while Northrop secretly, stealthily obtained dominance in the new technology market, then the plan worked.

But Northrop remained the company that survived but somehow never built anything. It still lost every design competition (its F-23 advanced tactical fighter design lost to Lockheed's F-22, even though everyone agreed yet again the F-23 was aerodynamically superior; B-2 production was terminated after only twelve aircraft had been built, at enormous expense). But the modern Pentagon has perfected the art of spending billions in designated congressional districts without ever actually delivering anything or getting anything into production.

The F-5S, an early version of the F-20 with a large wing for better short-field performance, was proposed as an alternative to the Saab Gripen to Sweden. The Gripen went into production, but only 153 were built for the Swedish Air Force in the period 1993 to 2005, compared to the 225 (plus 178 export orders) originally expected to be delivered in 1991 to 2001. Export sales were possibly representative of what the F-20 could have expected, and these developed poorly indeed. By 2006 only a handful were sold to South Africa, and possibly a few others leased to Hungary, in the face of fierce competition from the F-16C, MiG-29, Rafale, and Typhoon.

The Indian LCA turned into one of the most drawn-out development programs in history. Originally 150 were to be delivered in 1994 to 2001. India briefly considered purchasing the F-20 design and tooling in 1991, but reaffirmed its originally decision to proceed with a completely indigenous airframe and engine. So the first prototype did not fly until 1997. By 2005 only three prototypes were flying and production was years away.

The Lavi was resurrected in China as the F-10, which first flew in 1996. Development proceeded slowly, but by 2005 there were a handful flying and the way seemed clear for large-scale production to begin. As the Chinese aerospace industry developed further in the 21st Century, the Lavi might have been the seed that would destroy the aircraft industries of the West.

The Taiwanese ACF went into production in 1994 as the Ching Kuo, a flying counterpart of the twin-engined F-5X version of the F-20 favored by some traditionalists within Northrop. The program remained fairly secretive, but it seems the aircraft could not be considered very successful. By 2005 Taiwan had completed production after delivering only 130 aircraft. It was still seeking to purchase Typhoons, Rafales, or F-16s to match mainland China's license-built Su-27 and F-10/Lavi fighter aircraft types. The situation of thirty years earlier had not changed.

South Korea did not purchase the F-20 after the Blue House scandal, but instead bought more F-16s. However under the F-16 sales agreement they also developed a light 'trainer' aircraft powered by a single F404 engine dubbed the T-50. Production began in 2006 and the T-50 seemed a good contender to replace the T-38 in world trainer inventories.

The F-16 fulfilled its promise as the Fighter Deal of the 20th Century. By 2005 over 4,000 had been built (as against an original projected market of 3,000), and production continued into the indefinite future. The aircraft was no longer lightweight, having been loaded down in each successive version with more avionics and equipment, requiring more fuel, in turn requiring more powerful engines, which in turn required even more fuel. The mold line was interrupted by the lumps and bumps of conformal fuel tanks. A welter of avionics versions were operated by each customer. The price had bottomed out at $ 8 million at the high production rates of the F-16A/B version. This was the price the F-20 was competing against. But that price skyrocketed again to $ 23.3 million an aircraft as soon as the F-20 was canceled and the F-16C version introduced.

Even in the early 1980's the word was out that the F-16A was plagued with premature maneuvering flap cracking and wing fatigue problems. The F-16 had been designed to the maneuver life G-profile of the F-4E, the Air Force's air combat fighter at the time the F-16 was designed. But the fly-by-wire system of the F-16 allowed the pilots to pull incredibly high-G maneuvers with massive rates of onset. The pilot needed only to pull the joystick full back, and the unstable aircraft was commanded immediately into an 8 G turn, snapping the unwary pilots head back in the reclining seat (resulting in injury in many cases). The wing just wasn't designed for such repetitive maneuvers, and by the late-1980's it was apparent that all F-16A/B aircraft would require expensive wing replacements or retirement.

Once the F-20 was out of the way, the problem became public. Instead of paying to upgrade the aircraft to the design 8,000-hour airframe life, the Air Force scrapped virtually all of the 792 F-16A's and B's it had bought in the 1980's after just a decade of service. In the post-Cold War rundown, and the acquisition of over 1400 F-16C/D's, no one noticed. The aircraft retired included the low-ball F-16N Navy agressor and all but 24 of the F-16 ADF versions that had beaten out the F-20.

Just at the end of the F-20's brief saga the NATO states began development of fighters designed to match or exceed expected Soviet next-generation fighters. The French began development of the Rafale. The other major europeans states began development of the Euofighter Typhoon. With the competitive pressure of the Cold War removed, development was agonizingly slow. Test structural articles for the Eurofighter could be seen at European factories in 1988, but the first aircraft didn't fly until 1994, and production deliveries of limited versions of the aircraft would not begin until 2006. Compare this 20-year development cycle with the 20-month cycle of the F-20A.

The US Air Force next-generation-fighter was the stealthy Advanced Tactical Fighter. On the same Halloween night the F-20 was canceled, Northrop won a contract to build its F-23 prototype of the ATF. General Dynamics built its F-22 in competition. History tiresomely repeated itself. General Dynamics won the competition, with a design clearly inferior in every respect. There were stories that a bomber or reconnaissance version of the F-23 had secretly gone into limited production, but as of 2005 no such program had been publicly revealed.

The development of the F-22 was also incredibly protracted in the absence of cold war competitive pressure. It took 10 years from go-ahead decision to first flight of a production-representative aircraft, compared to 18 months for the F-20. It was another 10 years to first production delivery. By then the aircraft cost so much that the original planned delivery of 648 aircraft in the 1992 to 1998 period had shrunk to 120 in the 2007 to 2012 period, after which production would cease.

Historically each twin-engine fighter engendered a lightweight fighter using one of the same engine. This never happened according to plan, although it might as well have (F-4/F-104; F-15/F-16; F-18/F-20). Similarly the F-22's engine was used in a single-engine, not-quite-as-stealthy, hopefully-less-expensive fighter, the F-35 Joint Strike fighter. This was to be a return to the abominable F-111 concept - a single aircraft that was supposed to serve as an interceptor, fighter, bomber; in vertical-takeoff, conventional takeoff, and carrier-launch versions; built for the Navy, USAF, and Marines, with supposed vast export potential. The same countries that had been export launch customers for the F-16 bought into the F-35 as a next-generation replacement (in preference to the Eurofighter, which had no particular stealth credentials and represented no significant improvement over the F-16C).

But the United States had continued to fund weapons system development at cold-war levels through the 1990's while the rest of the world had not. That meant that the United States weapons technology had become costly but vastly in advance of that of other nations. The Americans jealously tried to protect this lead by refusing export of key technologies. By 2005 the F-35 was inevitably behind schedule, over budget, and its export potential in crisis. The main thing saving it was the incredible expense of the F-22, making the F-35 looking like a cheaper alternative. The cost and delays of the American 'next-generation' aircraft meant the F-15, F-16, and F-18 would remain into production well into the 21st Century, probably as much as 50 years after development had begun.

The T-38, F-5A and F-5E aircraft built by Northrop proved so durable and reliable that they needed no replacement. A variety of countries offered avionics upgrades and would inexpensively zero-time the airframes. Of the original US Air Force buy of 1189 T-38's, over 670 were still flying in 2005. Upgraded with modern avionics, they were expected to continue to meet USAF training needs until 2050 - by which time the airframes would be approaching 100 years old. Of 1199 F-5A/B aircraft delivered in the 1960's, 280 were still flying. Of 1350 F-5E aircraft, 530 were still flying. Avionics upgrades were available from Canada, Israel, the United States, Germany, Singapore, and Korea. Airframe updates could be conducted in Canada, Spain, Israel, Singapore, Korea, or Taiwan. No other fighter or trainer aircraft designed in the 1950's continued in service in such numbers, with the exception of the Russian MiG-21. Northrop had put itself out of the fighter business by building a design so classic, so durable, so correct, that it could not be replaced.