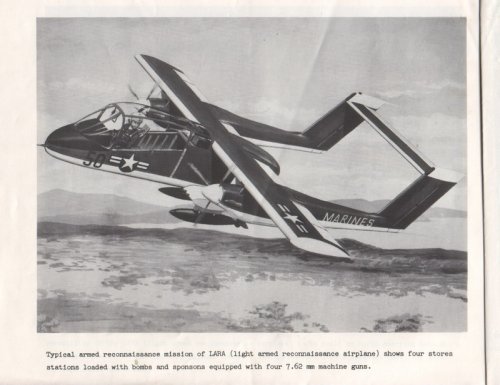

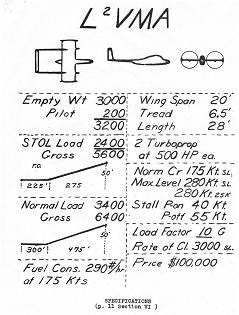

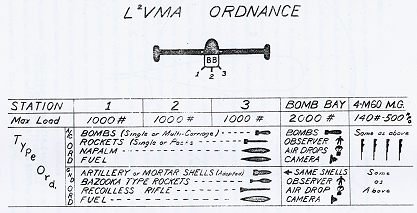

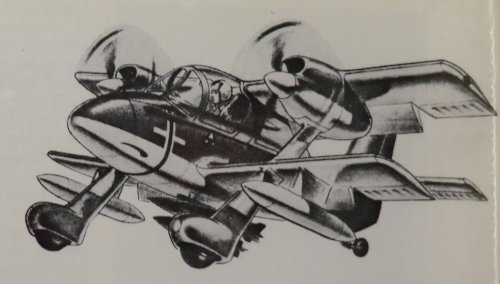

To cover the low end, WWII performance, I asked for a plane that could dive bomb like a Stuka or an SBD, maneuver like an SNJ/AT-6, and was as fast and strong as a Corsair. To be able to operate with supported troops, I asked for a small, easily supported and relatively inexpensive airplane, able to land and take off near a typical Battalion CP. For this requirement we came up with a wingspan limited to 20ft and a landing gear tread of 6.5ft for operating from roads, short take off and landing for small fields, and a backup seaplane capability. We aimed at the use of ground ordnance and communications to save weight, size and logistics without compromising (and possibly improving) close-in effectiveness. I also asked for ordnance near the centerline for accuracy, the best possible visibility, a seat for an observer and a small bomb bay for tactical flexibility.

I got these requirements from various sources. The dive bombing was based on my experience with the utility of this tactic and the notable results that had been achieved by aircraft like the Stuka and SBD. The AT-6 maneuverability was based on observation of Air Force airborne forward controllers (FACs) flying this type in Korea. My experience with the Corsair had impressed me with the value of its speed and strength for survivability against ground fire, and its ability to go fast or slow as the situation required, had been very effective. The P-38 had demonstrated the advantage of centerline guns for accuracy. Visibility and a back seat were needed for target acquisition and situational awareness. The bomb bay derived from the experiences of a Marine TBF torpedo bomber squadron during the Okinawa campaign (they flew almost three times as much as the fighter-bombers because their bomb-bays were in demand for so many "special" missions). The use of ground type ordnance was based on the fact that these weapons were tailored to their targets and should provide the maximum effect for their weight and logistic cost.

This was asking for a lot and, as experience ultimately showed, was essentially impossible in a normal "system" airplane. We were not designing a normal system airplane, however, and as we made our trade-offs we gave up a lot of what was standard because it wasn't absolutely required for the mission. This included things like ejection seats; aviation type navigation and communication equipment; and especially the single engine performance, fuel and equipment requirements associated with airways instrument flight.

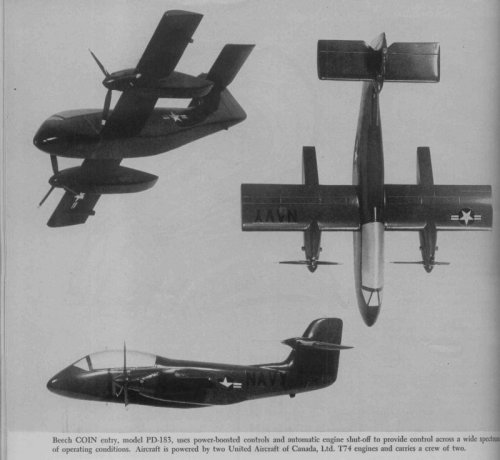

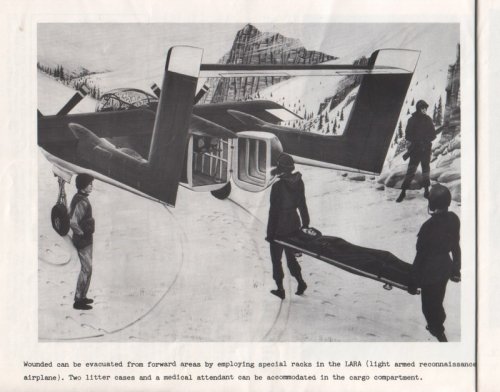

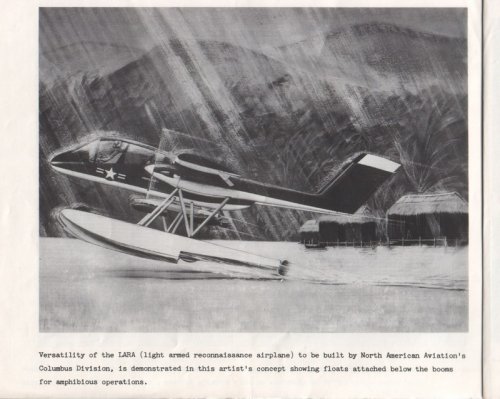

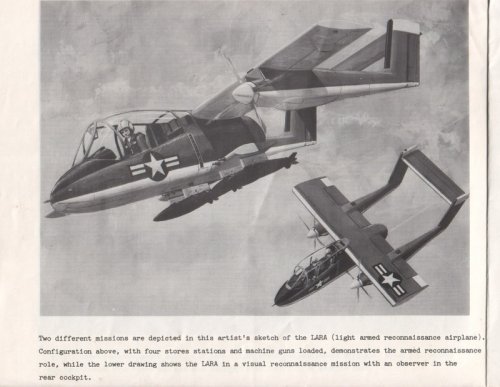

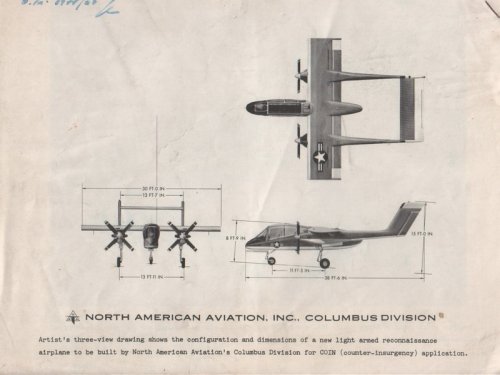

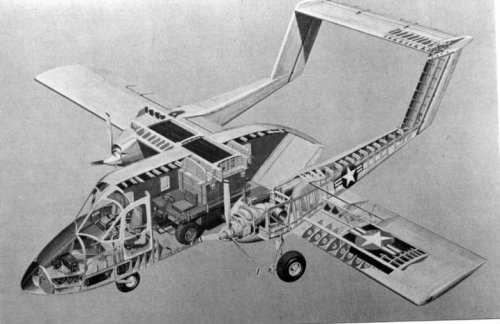

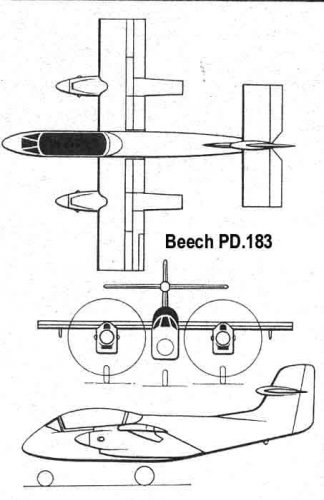

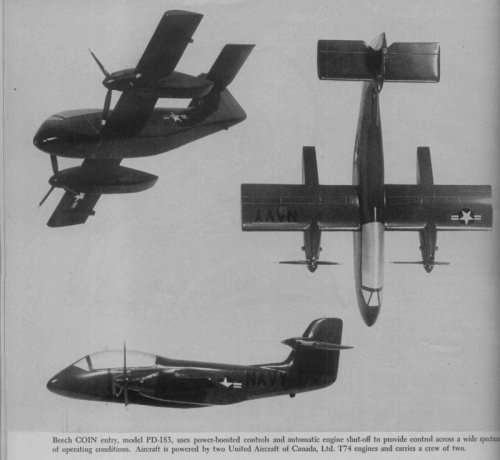

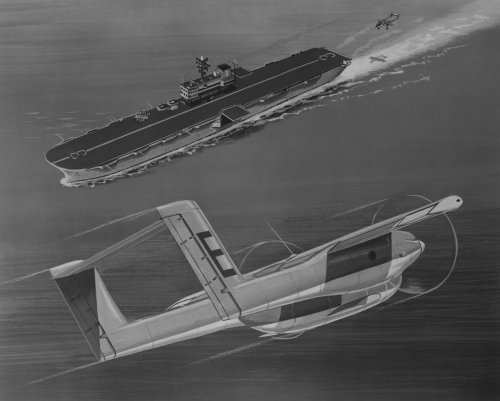

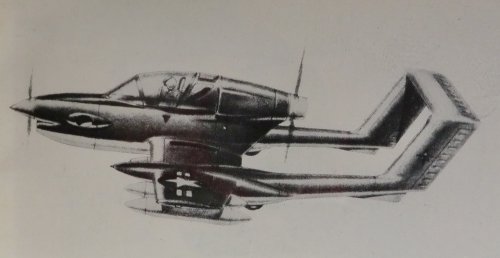

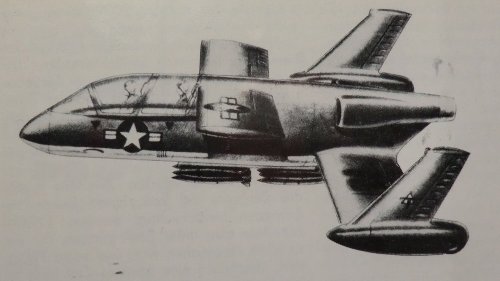

The design we came up with was definitely not "normal," but it could hopefully do tactically useful jobs that nothing else could do. To be able to operate near the supported troops it was small, with a wingspan of only 20ft and a tread of 6.5ft. to allow operations from dirt roads where even helicopters were restricted. It could take off and land over a 50ft. obstacle in only 500ft. and was to use ground ordnance and communications. The additional flexibility of water-based operations with retractable floats was also considered feasible. It had two turbo-prop engines in a twin boom configuration which allowed both internal and external ordnance carriage near the centerline. Weight empty was 330lbs; for STOL operations the weight was 5800lbs. and for runway operations the weight went up to 6600lbs. For "low end" performance top speed at sea level was between 265kts and 285kts depending on the load, and the stall speed was around 40kts. It had two seats, good air-to-air and air-to-ground visibility and a canopy that could be opened in flight for better visibility at night. It also featured 400lbs of armor and could pull up to 10 "G." It had taken a long six months, but we thought that the design was feasible, and that if built, could support revolutionary advances in CAS.