We should consider that drone technology is in its early stages of development, there has not yet been time or money to integrate it with artificial intelligence or quantum computing systems, a superweapon does not necessarily have to be big... we have not yet been able to defeat either the cold virus or the mosquitoes.

What is the best aerodynamic configuration for a fighter aircraft?

- Thread starter Ronny

- Start date

- Joined

- 11 March 2012

- Messages

- 3,244

- Reaction score

- 3,170

In the long run, I suspect that naval ships will carry a handful of standard electronic auto-pilots and use 3D printers to produce a variety of airframes for different missions. Just print up a new airframe and slip in the auto-pilot.Yes, but even UAV can have different aerodynamic configuration

View attachment 758642

During the early stages, you need long-endurance, high-altitude airframes to carry sensors high to surveil the largest area.

Once you figure out where the target is, you can send in faster low-altitude drones, etc.

Once you decide that this is a humanitarian mission, you can chose the high-bulk fuselage and install short-range wings since you only need to loft bags of rice past the first set of broken bridges.

- Joined

- 11 March 2012

- Messages

- 3,244

- Reaction score

- 3,170

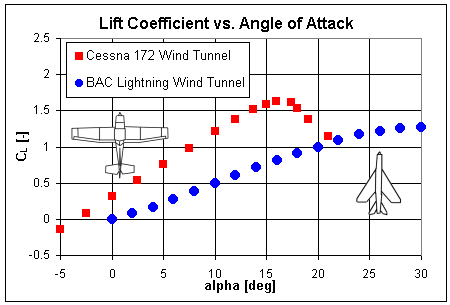

Delta wings' aerodynamics are far more complex than they appear to the naked eye.View attachment 758760

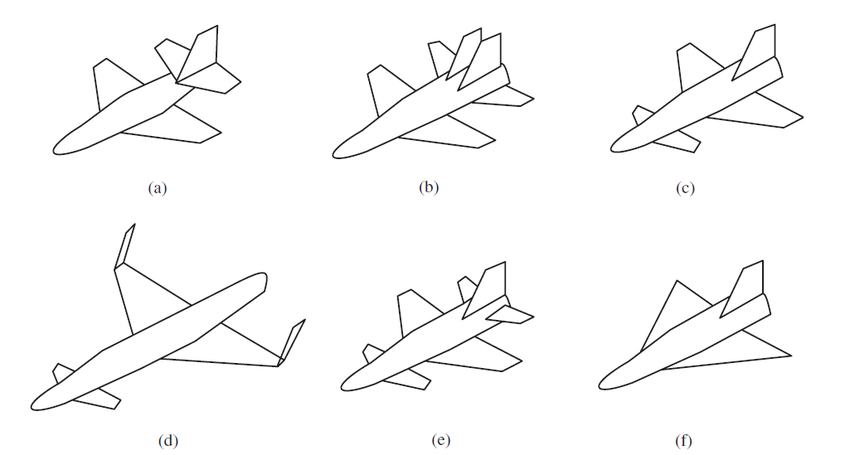

In My opinion these are the best configurations for modern 5th generation fighters.

Why Su-57?

Levcons do not generate the drag canards do and still control vortex position and aerodynamic center of lift position and are good for stealth.

Has TVC nozzles reducing the size of all moving vertical tails

The weapons bays on the lower part of the wing LEX, also reduces loss of lift and add space for a weapon

basically work as dropped wintips but carry a weapon

View attachment 758770

Widely separated engines improve TVC nozzles and add space for fuel and weapons and still generating fuselage lift.

It still has a horizontal tail, allowing good roll control when coupled with TVC nozzles

On Su-75 the lack of horizontal tail improves weight reduction and the extra area reflecting radar waves but still has an intake with a lower bump for the DSI intake by wrapping the intake lip around the fuselage.

For a 4th Generation

View attachment 758766

For a third generation

Rafale undoubtedly the best design because the close coupled canards assure the Delta wing LEX has extra strengthened vortices with some control, the intakes are simple fixed types but the semi ventral semi under the wing shape is good for sideslip and high AoA, definitively the most beautiful 4th generation fighter.

View attachment 758767

why? simple the best supersonic wing with the lowest radar signature for a third generation fighter was J-35 Drakken, the intakes were low drag and hided the engine fan compressor blades well.

(The Drakken wing is appearing again in the modern 6th generation designs)

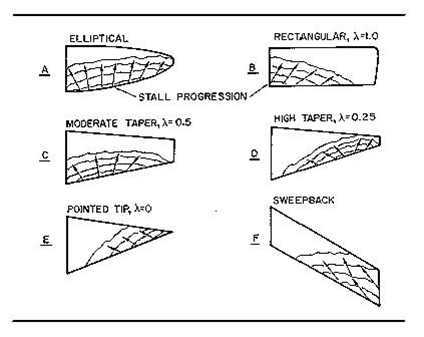

Sweep angle and leading edge radius can radically change airflow.

Consider how the first generation Mirages and Convairs needed conically-tapered leading edges to achieve their full potential.

Even on the diminutive Dyke Delta adding drooped cuffs to the outer leading edges dropped the landing speed by 6 knots. That made a big improvement for a small, fast airplane approaching a short runway.

Then look at the SAAB Draken's double-delta which looked promising, because it offered far greater internal volume. Internal volume is important when trying to hide bombs and extra fuel away from the prying eyes of radar. But Draken suffered from deep stalls because the steeply swept front chines continued producing lift long after the moderately-swept outer wing panels were stalled.

SAAB adopted the opposite form of leading edge sweep on their Viggen with shallow sweep on the inner wing panels, but steeper sweep on the outer wing panels. The break in the leading edge produces a vortex that helps tailor airflow over the main wing at steep angles-of-attack. The Indian TEJAS and latest Sukhoi 57 have similar cranked leading edges, plus leading edge flaps to further tailor airflow.

Canards and conventional tails will soon disappear as they reflect waaaay too much radar energy.

Vertical tails will disappear from sixth generation fighters because they reflect faaaaaaar too much radar energy.

While canards offer maneuverability advantages, I predict that future generations will be single-surface diamond wings with a variety of control surfaces. Just as deltas have little aerodynamic advantage over swept wings .... deltas simplify transferring structural loads from one wing-tip to the other wing-tip via a straight rear spar.

Diamond wings offer little structural advantage over deltas, but they do allow mounting tail control surfaces farther away from the center-of-gravity which improves their leverage/tail moment arm (see Su-57).

Eventually movable control surfaces will be replaced by blown surfaces that have smaller radar returns.

F-14ATomcat

ACCESS: Secret

- Joined

- 26 May 2024

- Messages

- 423

- Reaction score

- 730

I agree, unless there is a radar advance that renders stealth useless ( I think physics will not allow stealth to be viable for long) I think Drones, high speeds are the way to go.Delta wings' aerodynamics are far more complex than they appear to the naked eye.

Sweep angle and leading edge radius can radically change airflow.

Consider how the first generation Mirages and Convairs needed conically-tapered leading edges to achieve their full potential.

Even on the diminutive Dyke Delta adding drooped cuffs to the outer leading edges dropped the landing speed by 6 knots. That made a big improvement for a small, fast airplane approaching a short runway.

Then look at the SAAB Draken's double-delta which looked promising, because it offered far greater internal volume. Internal volume is important when trying to hide bombs and extra fuel away from the prying eyes of radar. But Draken suffered from deep stalls because the steeply swept front chines continued producing lift long after the moderately-swept outer wing panels were stalled.

SAAB adopted the opposite form of leading edge sweep on their Viggen with shallow sweep on the inner wing panels, but steeper sweep on the outer wing panels. The break in the leading edge produces a vortex that helps tailor airflow over the main wing at steep angles-of-attack. The Indian TEJAS and latest Sukhoi 57 have similar cranked leading edges, plus leading edge flaps to further tailor airflow.

Canards and conventional tails will soon disappear as they reflect waaaay too much radar energy.

Vertical tails will disappear from sixth generation fighters because they reflect faaaaaaar too much radar energy.

While canards offer maneuverability advantages, I predict that future generations will be single-surface diamond wings with a variety of control surfaces. Just as deltas have little aerodynamic advantage over swept wings .... deltas simplify transferring structural loads from one wing-tip to the other wing-tip via a straight rear spar.

Diamond wings offer little structural advantage over deltas, but they do allow mounting tail control surfaces farther away from the center-of-gravity which improves their leverage/tail moment arm (see Su-57).

Eventually movable control surfaces will be replaced by blown surfaces that have smaller radar returns.

I like the Rafale configuration, that is in my opinion the ideal configuration, but the trend is for tailess aircraft that to be honest are ungainly aircraft, the aerodynamic controls are the best, thrust vectoring reduces thrust,, unless they develop some anti gravity propulsion system, aerodynamic controls are no going to disappear.

All the flying doritos are crap, the ideal fighter always will need speed and agility, laser or high energy weapons could change that, but any technology has advantages and cons.

This the way i would design a fighter, LEVCONs, Draken style wings and Thrust vectoring

Last edited:

- Joined

- 3 June 2011

- Messages

- 18,297

- Reaction score

- 12,113

Yep. A bit like saying the F-102 had the same wing as Concord.Superficially looking similar is not the same as "basically the same". The flow physics is significantly impacted by multiple other features e.g. leading edge sharpness, LE crank location, TE crank location, fences, LE devices etc.

The wings are very very different with different performance

C0de.R.E.A.M.

Code Rules Everything Around Me.

- Joined

- 28 January 2025

- Messages

- 27

- Reaction score

- 32

Hmm... well if we’re throwing real-world limitations out the window, Variable Swept is hard to beat in my opinion. It gives the best of both worlds - high lift at low speeds and sleek efficiency at high speeds. Unlike fixed-wing designs that are always a compromise, VG lets you adapt in real time depending on mission needs. It’s why the F-14 excelled in both dogfighting and long-range interception.

The only reason we don’t see VG anymore is cost, weight, and maintenance headaches, but if we’re ignoring all that, why not go for the most versatile aerodynamic design.

On the other hand, if we consider and include real-world limitations, like production cost, maintenance, complexity and the desired stealth, then I think the best aerodynamic configuration would likely be close coupled canards (like the Eurofighter Typhoon and J-20). They also enhance supersonic agility, helping the aircraft maintain control at high AoA, and can be stealth-optimized better than long-arm canards. That’s why modern fighters like the Typhoon, Rafale, and J-20 use them, it’s a good mix of aerodynamics, efficiency, and real-world maintenance/feasability.

If the goal is supersonic cruise efficiency and sustained high-speed flights then long-arm canards (Saab Gripen) would be good too, although they tend to increase RCS more than close-coupled.

The only reason we don’t see VG anymore is cost, weight, and maintenance headaches, but if we’re ignoring all that, why not go for the most versatile aerodynamic design.

On the other hand, if we consider and include real-world limitations, like production cost, maintenance, complexity and the desired stealth, then I think the best aerodynamic configuration would likely be close coupled canards (like the Eurofighter Typhoon and J-20). They also enhance supersonic agility, helping the aircraft maintain control at high AoA, and can be stealth-optimized better than long-arm canards. That’s why modern fighters like the Typhoon, Rafale, and J-20 use them, it’s a good mix of aerodynamics, efficiency, and real-world maintenance/feasability.

If the goal is supersonic cruise efficiency and sustained high-speed flights then long-arm canards (Saab Gripen) would be good too, although they tend to increase RCS more than close-coupled.

F-14ATomcat

ACCESS: Secret

- Joined

- 26 May 2024

- Messages

- 423

- Reaction score

- 730

Variable geometry wing are not needed today, because they want the less moving parts and less fuselage discontinuities, thus they are looking for tailess cranked deltas or similar designs.Hmm... well if we’re throwing real-world limitations out the window, Variable Swept is hard to beat in my opinion. It gives the best of both worlds - high lift at low speeds and sleek efficiency at high speeds. Unlike fixed-wing designs that are always a compromise, VG lets you adapt in real time depending on mission needs. It’s why the F-14 excelled in both dogfighting and long-range interception.

The only reason we don’t see VG anymore is cost, weight, and maintenance headaches, but if we’re ignoring all that, why not go for the most versatile aerodynamic design.

On the other hand, if we consider and include real-world limitations, like production cost, maintenance, complexity and the desired stealth, then I think the best aerodynamic configuration would likely be close coupled canards (like the Eurofighter Typhoon and J-20). They also enhance supersonic agility, helping the aircraft maintain control at high AoA, and can be stealth-optimized better than long-arm canards. That’s why modern fighters like the Typhoon, Rafale, and J-20 use them, it’s a good mix of aerodynamics, efficiency, and real-world maintenance/feasability.

If the goal is supersonic cruise efficiency and sustained high-speed flights then long-arm canards (Saab Gripen) would be good too, although they tend to increase RCS more than close-coupled.

The Mirage family exemplifies well this trend

In the 1960s the Mirage family evolved in what was basically "the same fuselage" but different wings types.

If you look at the Mirage 3, Mirage G, Mirage F1 or Mirage NG, you can see why they went for Mirage 2000 in the 1970s

VG wings increase weight that basically using the same fuselage still will give you higher wing loading

Ideally a horizontal tail and less swept wing than a delta wing still gives the most conventional configuration that gives the most conventional control and allows less loss of main wing lift.

However due to stealth tailless cranked deltas are now chosen.

Variable geometry wings are well suited for large aircraft like Tu-160 or B-1B that require fast speeds, fast cruise speeds and STOL, this can not be achieved with the current flying wings B-21 or B-2.

Tu-160 can do attacks from far away distances and still survive.

Canards and delta wing configurations are the best in terms high speed, excellent agility specially if the fuselage is lighter, so F-14 can not compete with rafale, a lighter fuselage can out turn the F-14 simply because it has a very light fuselage and low wing loading

Cutaway

ACCESS: Restricted

Would a folding-wing configuration (IE: XB-70 Valkyrie) have the same capability as a variable geometry wing for a fighter aircraft?

No, XB-70 configuration is optimized for cruising at high Mach speed. Swing wing is supposed to be optimized at wide range of speed: high lift at low swept angle, low drag at high swept angleWould a folding-wing configuration (IE: XB-70 Valkyrie) have the same capability as a variable geometry wing for a fighter aircraft?

F-14ATomcat

ACCESS: Secret

- Joined

- 26 May 2024

- Messages

- 423

- Reaction score

- 730

For a decade and a half, many fighter tacticians have stressed the paramount importance of being able to sustain a high turn rate at high Gs. The rationale was that with such a capability, enemy aircraft that cannot equal or better the sustained turn rate at high Gs could not get off a killing shot with guns or missiles.If the objective is high speed cruise and carrying lots of bombs then perhaps an updated F-16XL cranked delta. The F-16XL's disadvantage was less maneuverability.

With developments in missiles that can engage at all aspects, and as a result of having evaluated Israeli successes in combat, the tacticians are now leaning toward the driving need for quick, high-G turns to get a “first-shot, quick-kill” capability before the adversary is able to launch his missiles. This the F-16XL can do. Harry Hillaker says it can attain five Gs in 0.8 seconds, on the way to nine Gs in just a bit more time. That’s half the time required for the F-16A, which in turn is less than half the time required for the F-4. The speed loss to achieve five Gs is likewise half that of the F-16A.

All of these apparent miracles seem to violate the laws of aerodynamics by achieving greater range, payload, maneuverability, and survivability. Instead, they are achieved by inspired design, much wind-tunnel testing of shapes, exploitation of advanced technologies, and freedom from the normal contract constraints.

The inspired design mates a “cranked-arrow” wing to a fifty-six inch longer fuselage. The cranked-arrow design retains the advantages of delta wings for high-speed flight, but overcomes all of the disadvantages by having its aft portion less highly swept than the forward section. It thus retains excellent low-speed characteristics and minimizes the trim drag penalties of a tailless delta.

Although the wing area is more than double that of the standard F-16 (633square feet vs. 300 square feet), the drag is actually reduced. The skin friction drag that is a function of the increased wetted (skin surface) area is increased, but the other components of drag (wave, interference, and trim) that are a function of the configuration shape and arrangement are lower so that the “clean airplane” drag is slightly lower during level flight, and forty percent lower when bombs and missiles are added. And although the thrust-to-weight (T/W) ratio is lower due to the increased weight, the excess thrust is greater because the drag is lower – and excess thrust is what counts.

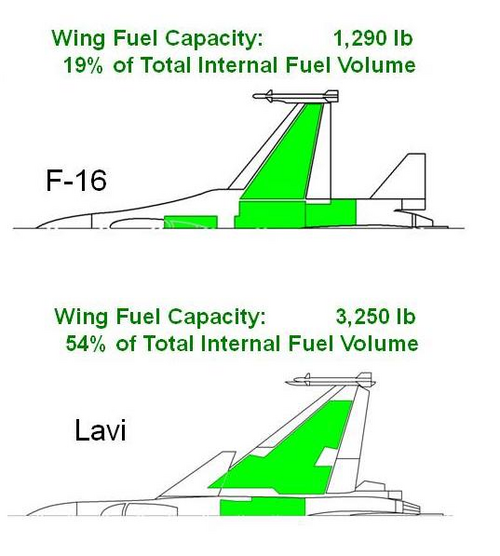

The larger yet more efficient wing provides a larger area for external stores carriage. At the same time, the wing’s internal volume and the lengthened fuselage enable the XL to carry more than eighty percent more fuel internally. That permits an advantageous tradeoff between weapons carried and external fuel tanks.

Through cooperation with NASA, more than 3,600 hours of wind-tunnel testing refined the shapes that Harry Hillaker and his designers conceived. More than 150 shapes were tried, with the optimum design now flying on the two aircraft at Edwards.

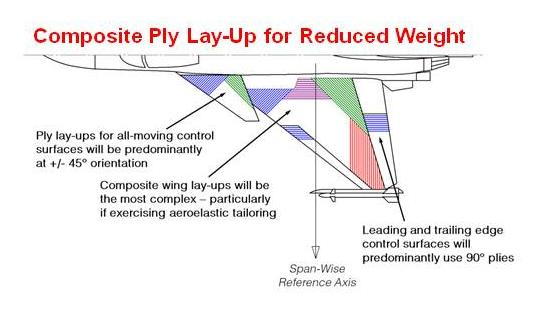

As an additional technology, the XL’s wing skins are composed of an advanced graphite composite material that has a better strength-to-weight ratio than aluminum, is easier to form to the compound wing contours, and has higher stiffness to reduce undesirable flexibility effects.

Two features of the basic F-16 played an important part in readily accommodating what appears to be a drastic change in configuration. First, the modular construction of the airframe allows major component changes with local modification only. And second, the redundant quadriplex fly-by-wire flight control system has the inherent ability (one of its strongest features) to accommodate configuration changes readily.

The modular component construction permitted the addition of a twenty-six-inch “plug” between the center and aft fuselage components to carry the additional wing loads, and a thirty-inch “plug” between the cockpit and inlet component to accommodate the increased wing chord (length). Each “plug” is added at an existing manufacturing splice or mating point.

Finally, since the design and fabrication was entirely a company project, the design team was not constrained by irrelevant requirements and specifications. As Harry Hillaker puts it: “Every piece on this aircraft earned its way on.” That design freedom kept the team concentrating on achieving “performance objectives” in this derivative of the F-16.

Late in 1980, General Dynamics approached the Air Force’s Aeronautical Systems Division for cooperation and support in flight-testing the design. USAF supplied the two test aircraft to be modified to the F-16XL configuration, two turbofan engines, a new two-place cockpit, and funding for the flight-testing. A Pratt & Whitney F100 engine powers the single-seat F-16XL; its sister two-place aircraft is powered by a General Electric F110 derivative fighter engine.

The Revolutionary Evolution of the F-16XL | Air & Space Forces Magazine

This dual role fighter candidate has one foot in the present ad one foot in the future.

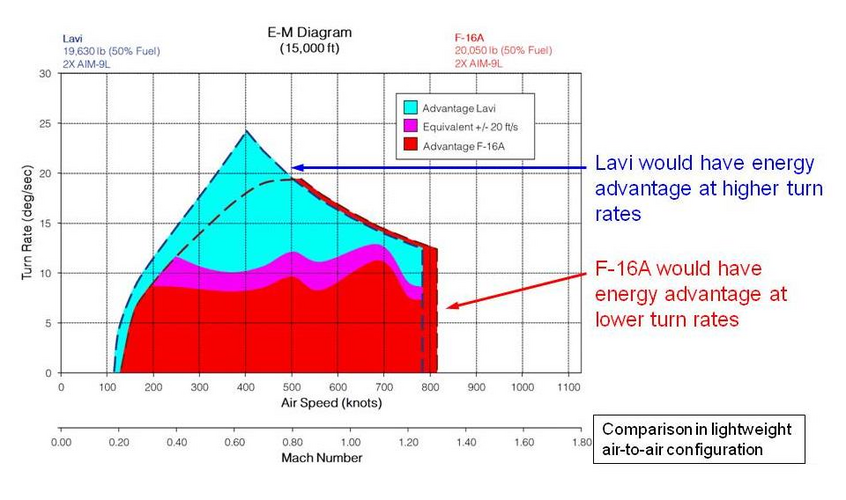

Although the flight performance envelope was not completely explored, it seems probably that the Lavi would have been at least the equal of the F-16C/D in most departments, and possible even superior in some. It had been calculated that the Lavi could reef into a turn a full half second quicker than the F-16, simply because a conventional tailed fighter suffers a slight delay while the tailplane takes up a download, whereas with a canard fighter reaction is instantaneous. By the same token, pointability of canard fighters is quicker and more precise. Where the Lavi might really have scored heavily was in supersonic maneuverability, basically due to the lower wave drag of a canard delta.

Thrust-to-weight ratio: 0.94 at normal take-off weight. Wing loading: 302 kg/m2 at normal take-off weight and 523 kg/m2 at maximum take-off weight. Sustained air turning rate: 13.2o/s at Mach 0.8 at 4,757 m. Maximum air turning rate: 24.3o/s at Mach 0.8 at 4,757 m. Take-off distance: 305 m at maximum take-off weight. G limit: + 9 g.

Israel Aircraft Industries (IAI) Lavi

Encyclopedia of Jewish and Israeli history, politics and culture, with biographies, statistics, articles and documents on topics from anti-Semitism to Zionism.

On this basis, we might expect the unstable Lavi, with its much lower wing loading and unstable aerodynamics to have great ITR, while the Tigershark ITR would be reduced compared to the Lavi and the F-16. Both the F-16 and the Tigershark benefit from wing leading edge strakes, and, notably, all aircraft claim to be able to operate up to a 9g structural limit. The real issue here is for how much of the flight envelope is this capability available, and how much energy will be lost in such a manoeuvre.

On sustained turn rate, the trade-offs are more complex, but it is apparent that the F-16/79 is likely to be handicapped by its lower thrust to weight ratio. Note that the thrust used is a short-term power plus mode. At normal thrust, the F-16/79 has a thrust to weight ratio of around 0.75. The low aspect ratio of the Lavi, and its slightly lower thrust-to-weight ratio are likely to reduce STR, but the much lower wing loading will counter this to some extent.

Thrust to weight ratio is particularly important, as a high thrust to weight ratio will enable high energy manoeuvrability. This will allow a turning fight to be readily taken into the vertical, and, in BVR combat will allow rapid cycling between engagement, missile release, disengagement, acceleration and re-engagement. Of these four aircraft, the F-16C has a definite advantage in energy manoeuvrability, and the F-16/79 will be at a disadvantage.

The Table below presents some limited data for the four aircraft. The data reflect what could be gleaned from the web, and is not fully defined, in that aircraft configuration, altitude and Mach number are not generally available to fully define the quoted figures. As all aircraft claim to be capable of generating 9g, the small variation in ITR figures probably reflects differing altitude or speed conditions, although the higher value for the Lavi may reflect both its low wing loading and its unstable aerodynamics. The ITR for the F-16/79 is based on the assumption that the aircraft can reach the same CLmax, and has the same structural limits as the F-16. The F-16/79 would lose energy much faster than the F-16 due to its much lower thrust.

It is notable that the higher thrust to weight ratio of the F-16C gives a significant benefit in Sustained Turn Rate – the figure noted comes from a dataset that suggests the F-16 is structurally limited in STR as well as ITR. The slightly higher ITR figure is at a lower speed, where the aircraft is lift-limited rather than g-limited. The impact of the low thrust of the F-16/79 is evident in comparison of its sustained turn performance with the F-16, and the F-20 Tigershark achieves similar STR, the higher thrust to weight ratio somewhat offsetting its higher wing loading. It should not be forgotten that the Lavi was really well ahead of its time in aerodynamics, control system and mission system design. Its nearest equivalent would probably be the Gripen, which made its first flight in December 1988, some 2 years after the Lavi.

F-20 versus Lavi: The Tigershark, the Young Lion and the Viper

This is a story about US foreign policy and its intersection with aerospace. The relevant period is the ‘80s, but the interweaving of US industrial, trade, defence and foreign policy settings can b…

Last edited:

lastdingo

Blogger http://defense-and-freedom.blogspot.de/

1 - so can truck trailers, which win the cost efficiency comparison hands downFighters are much weaker than SAM in defense but much stronger in offense:

1- They can attack ground targets with immunity if using long range cruise missiles.

2- They can deal with nap of the earth targets easily because they can fly at high altitude

3- Force concentration is significantly easier with fighters because they can relocate quickly

2 - IF they can fly high. Fighters cannot at the Ukrainian front because area air defences don't permit it

3 - the munitions need to be relocated as well, so missiles launched out of ISO cpntainers compete well

Dassault by the mid-60's explored delta, swept and VG in close succession.

The Mirage V (delta) passed its fuselage to the F1 (swept) itself a 0.80 Mirage F2 / F3... which passed their fuselage to the Mirage G. Finally the 2000 returned to the Mirage III delta except with FBW.

Sukhoi, too, explored similar variations.

The Mirage V (delta) passed its fuselage to the F1 (swept) itself a 0.80 Mirage F2 / F3... which passed their fuselage to the Mirage G. Finally the 2000 returned to the Mirage III delta except with FBW.

Sukhoi, too, explored similar variations.

F-14ATomcat

ACCESS: Secret

- Joined

- 26 May 2024

- Messages

- 423

- Reaction score

- 730

The Mirage Family is similar to the F-16 Family.Dassault by the mid-60's explored delta, swept and VG in close succession.

The Mirage V (delta) passed its fuselage to the F1 (swept) itself a 0.80 Mirage F2 / F3... which passed their fuselage to the Mirage G. Finally the 2000 returned to the Mirage III delta except with FBW.

Sukhoi, too, explored similar variations.

The Mirage started with Deltas, and ended with Deltas, from Mirage 1 to Mirage 4000.

But also had foreign derivatives such as the Kfir and Cheetah

The F-16 to F-16XL and Lavi,, IDF Ching Kuo and Mitsubishi F2 are also YF-16 derivatives

These two families show different aerodynamic configurations that suit well this topic.

Personally I like the Mirage 4000 the most and Rafale is also a mirage derivative basically a very improved Mirage 4000.

Aircraft need to get lighter, lighter materials, higher thrust engines with lower fuel consumption, add the Delta canard and you get the most practical configuration.

However F-16XL and Lavi achieved higher ITR than F-16As but in STR still F-16A/C were competitive

Lavi - An Engineer's Perspective

The Lavi fighter program was the largest weapons development effort ever undertaken by the State of Israel - embodying a unique, Israeli ...

SAAB did something similar from the Cranked delta compound delta Draken to Gripen

At supersonic speeds, and especially as Mach number increased beyond 1.2,the cranked-arrow wing offered improved lift to drag characteristics at both cruise and moderate angles of attack compared to the others. At supersonic speeds and at higher lift conditions,the cranked-arrow wing was equal tothe other candidates in the improvements it offered compared to the baseline F-16. Drag with the cranked arrow wing during wings-level acceleration in 1-g flight was comparable to that of the baseline F-16, the equal weight composite, and the canard delta, and it was significantly better than that of the forward-swept wing.At Mach 2.0, only the canard-delta and cranked-arrow planforms showed the potential to provide increased L/D. Both of these planforms were comparable in terms of cruise efficiency at all speeds from Mach 0.9 toMach 2.0. The canard-delta and the cranked arrow were equal to the baseline F-16 at Mach 0.9, and their L/D ratios were better across the entire supersonic speed range.GD studies also indicated that the spanwise location of the wing crank had a significant effect on subsonic and transonic lift-to-drag ratios. The cranked-arrow wing could be optimized to retain a subsonic efficiency (as measured by L/D) that was closely comparable to that of the F-16. An additional advantage was its very significant design and integration advantages. These included a greatly increased wing areathat provided much more volume for additional fuel and an increased wing chord that allowed for efficient conformal weapons carriage. However, studies and analyses of the competing wing planforms conclusively showed that the cranked-arrow wing traded off sustained maneuver capability for decreased drag during 1-g acceleration, better L/D at supersonic speed, a

Last edited:

- Joined

- 29 November 2010

- Messages

- 1,772

- Reaction score

- 3,469

I'm surprised we don't see more fighter jets with a lambda wing.

it was proposed on McDonnell Douglas' JAST proposal, BAe Replica, among others.

it was proposed on McDonnell Douglas' JAST proposal, BAe Replica, among others.

- Joined

- 11 March 2012

- Messages

- 3,244

- Reaction score

- 3,170

That extended center trailing edge has many of the same pitch stability-and-control advantages of a conventional configuration, but is more stealthy because it is missing a few yards/meters of wing trailing edge and tail leading edge to reflect radar returns.I agree, unless there is a radar advance that renders stealth useless ( I think physics will not allow stealth to be viable for long) I think Drones, high speeds are the way to go.

I like the Rafale configuration, that is in my opinion the ideal configuration, but the trend is for tailess aircraft that to be honest are ungainly aircraft, the aerodynamic controls are the best, thrust vectoring reduces thrust,, unless they develop some anti gravity propulsion system, aerodynamic controls are no going to disappear.

All the flying doritos are crap, the ideal fighter always will need speed and agility, laser or high energy weapons could change that, but any technology has advantages and cons.

View attachment 760508

View attachment 760510

This the way i would design a fighter, LEVCONs, Draken style wings and Thrust vectoring

A secondary benefit is the longer center chord lends a larger Reynolds Number that helps improve lift-to-drag ratios. See Baranby Wainfain's Facetmoble to better understand how low aspect-ratio deltas fly.

F-14ATomcat

ACCESS: Secret

- Joined

- 26 May 2024

- Messages

- 423

- Reaction score

- 730

Thanks, I think Draken in many ways was ahead of its time, at least in aerodynamics and in some way stealth.That extended center trailing edge has many of the same pitch stability-and-control advantages of a conventional configuration, but is more stealthy because it is missing a few yards/meters of wing trailing edge and tail leading edge to reflect radar returns.

A secondary benefit is the longer center chord lends a larger Reynolds Number that helps improve lift-to-drag ratios. See Baranby Wainfain's Facetmoble to better understand how low aspect-ratio deltas fly.

I think each design bureau they try to think priorities, once they decide priorities go for the most compromising configuration modern aircraft are going for pure stealth and little performance,

In the 1980s Gripen or Rafale were going for speed and a decent maneuverability.

The F-15 and F-14 were designed with speed in mind and maneuverability in mind.

The most important in any aircraft is highest lift, lowest drag and highest thrust but that is speed and altitude dependent, I mean it depends in terms of what materials are used and what engines specific fuel consumption and payload requirements they have.

I mean If I would not care for stealth I would go for F-18A just for aesthetics.

If I am honest I hope better radars render stealth useless because modern fighters in my opinion are getting uglier by the minute and are going for pure stealth.

The only stealth fighter I like is F-22 and to some Su-57 since it is a Flanker/Fulcrum with stealth but with balance, not to much stealth regardless people criticize them, they still look cool to my eyes, but the rest well I do not like them very Much.

My favorite canard delta wing is Lavi followed by Mirage 4000, of course at my 53 years of age, I still prefer MiG-29 or F-14 as my favorite jet fighters.

If i would say by time line I would say in the 1940s my ideal fighter would be P-51 or Yak-9. followed by Do-335 as heavy fighter.

Of early jet age my favorite fighter would had been He-162.

in the 1950s my ideal fighter was A-5 Vigilante well not a fighter but still my favorite 1950s aircraft but as a fighter F-11 tiger, but I think the most practical aircraft of early 1950s was the F-101 Voodo and MiG-15.

In the 1960s well perhaps the F-4E was the best

In the 1970s Aj-37 Viggen and F-14, 1980s MiG-29

In the 1990s well the Rafale and in the 2000s F-22

But I am honest all aircraft have beauty and wisdom

Last edited:

F-14ATomcat

ACCESS: Secret

- Joined

- 26 May 2024

- Messages

- 423

- Reaction score

- 730

That extended center trailing edge has many of the same pitch stability-and-control advantages of a conventional configuration, but is more stealthy because it is missing a few yards/meters of wing trailing edge and tail leading edge to reflect radar returns.

A secondary benefit is the longer center chord lends a larger Reynolds Number that helps improve lift-to-drag ratios. See Baranby Wainfain's Facetmoble to better understand how low aspect-ratio deltas fly.

I think the best fighter it will depend in the needs, time period and the technical solutions in terms of efficiency in performance versus costs but for example in the 1940s I think the best solution for a heavy fighter was the Do-335, I mean what a smart idea, most fighter used engines on the wings.

The reason I like F-14 well is because the aircraft is an entire flying surface and the VG wing makes it look more organic, more alive like a bird that opens its wings

The Flanker, Fulcrum or Felon have followed that philosophy and I like the Draken because for a wing tailess aircraft with little drag it is the most practical from my point of view because even the intakes are part of the wings and the compound delta solution was ahead of its time

I mean the design is pretty smart, the MiG-15 also was very smart design

The intake ducts were quite smart, allowing for a fighter that basically the air intake ducts surrounded the cockpit and allowed a very small cross section.

i mean for a 1950s aircraft was a very smart design a jet engine with wings and a cockpit.

I mean other jet aircraft with a Pitot intake were beautiful like J-29 Tunnan, but MiG-15 was in my opinion the most practical

On Tunnan and F-86 the intake duct was under the cockpit, well perhaps the air flow was better, cleaner perhaps but the cross section was bigger, and on Tunnan the fuselage fairing ended on a separated tail

So I think designs always have good ideas, personally I always have liked Swedish aircraft Viggen is my favorite Swedish aircraft, and while I have some Finnish ancestry, very little only 3% and I can say some of my genes are related to Sweden to some degree since Finland once was part of the Swedish empire , so well I have always like Swedish aircraft but my DNA test made me a bit happy.

Last edited:

Shaman Harris

ACCESS: Confidential

- Joined

- 26 March 2025

- Messages

- 51

- Reaction score

- 23

Long arm canard,to eat the Americans at retaining energy,so long F-16 E-M theory

F-14ATomcat

ACCESS: Secret

- Joined

- 26 May 2024

- Messages

- 423

- Reaction score

- 730

Interesting but I think the problem with aircraft are the specifications, the flight envelop, and the configuration chosenLong arm canard,to eat the Americans at retaining energy,so long F-16 E-M theory

Each configuration has advantages and disadvantages.

Supersonic aerodynamic characteristics of canard, tailless, and aft-tail configurations for 2 wing planformsAerodynamic characteristics of canard, tailless, and aft tail configurations were compared in tests on a general research model (generic fuselage without canopy, inlets, or vertical tails) at Mach 1.60 and 2.00 in the Langley Unitary Plan Wind Tunnel. Two uncambered wing planforms (trapezoidal with 44 deg leading edge sweep and delta with 60 deg leading edge sweep) were tested for each configuration. The relative merits of the configurations were also determined theoretically, to evaluate the capabilities of a linear theory code for such analyses. The canard and aft tail configurations have similar measured values for lift curve slope, maximum lift drag ratio, and zero lift drag. The stability decrease as Mach number increases is greatest for the tailless configuration and least for the canard configuration. Because of very limited accuracy in predicting the aerodynamic parameter increments between configurations, the linear theory code is not adequate for determining the relative merits of canard, tailless, and aft tail configurations.

Supersonic aerodynamic characteristics of canard, tailless, and aft-tail configurations for 2 wing planforms - NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS)

Aerodynamic characteristics of canard, tailless, and aft tail configurations were compared in tests on a general research model (generic fuselage without canopy, inlets, or vertical tails) at Mach 1.60 and 2.00 in the Langley Unitary Plan Wind Tunnel. Two uncambered wing planforms (trapezoidal...

installed in front of the main wing, which is like installing a huge horn headlight and is easily noticed in

dark and open areas. This is because, for the movable canard, the gap caused by the movement between

it and the fuselage is directly exposed to the radar detection in front of the aircraft, increasing the

possibility that the RCS characteristics of the fuselage are detected simultaneously [5]. But for the

horizontal tail, which is located behind the main wings, the main wing blocks approximately most of the

gaps that are prone to exposure risks when the horizontal tail moves, which greatly reduces the

possibility of being detected by radar from the front. Therefore, conventional layout aircraft are ahead of

canard layout aircraft in stealth

the difficulty is the combination of facts in the design it self

Last edited:

Similar threads

-

Questions regarding the shape of the Me 262 and Focke-Wulf 187 fuselage.

- Started by ThePolishAviator

- Replies: 22

-

-

-

-