saintkatanalegacy

Little Miss Whiffologist

- Joined

- 31 March 2009

- Messages

- 718

- Reaction score

- 17

wow, great rib model!

thanks

thanks

This photo comes from a vast archive of Original AP, UPI and various other news service photos.

Wire Photo. 10x8. 1/14/1969. Washington, DC. Artist's concept of the Navy's new supersonic, carrier-based fighter, the F-14A. Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corp. has been selected as prime contractor. The F-14A will be a two-place aircraft with tandem seating and will be equipped with Pratt & Whitney TF30-P-12 afterburning turbofan engines. Present plans call for first flight in early 1971 and operation with the fleet in 1973.

EEP1A said:The picture I posted as MDD 225 was taken from Japanese magazine AIREVIEW March 1969, but erroneously captioned "winning design of F-14A by Grumman".

On the next issue, the mock up photos of the real Grumman design was published but still saying that "the rendering of the last month issue was one of the designs studied by Grumman but the mock up shows the final design."

Cheers,

EEP1A

The F-15N Sea Eagle was a proposed variant of the F-15 Eagle as an alternative to the F-14 Tomcat in Navy service.

During the development phase of the Eagle, the US Navy was instructed in July 1971 to take a look at a possible navalized version of the Eagle, provisionally designated F-15N. At that time, the Navy was satisfied with its Grumman F-14A Tomcat, which was then in its flight test phase, and was less than enthusiastic about a "Sea Eagle", unofficially known as "Seagle".

The navalized F-15N Sea Eagle initial proposed version was estimated to weigh 2300 pounds more than the F-15A.[1] The US Navy was not impressed with this F-15N version since it would be unable to carry or launch the AIM-54A Phoenix long-range missile.

The F-15N-PHX was another proposed naval version capable of carrying the AIM-54 Phoenix missile. The F-15N and F-15N-PHX featured folding wingtips, reinforced landing gear and a stronger tail hook for shipboard operation.[1]

The US Senate briefly revived the carrier-based Eagle idea in March 1973. However, the Navy decided instead to go with a mix of F-14 Tomcats and F/A-18 Hornets, and the F-15N was never ordered.

overscan said:http://www.secretprojects.co.uk/forum/index.php/topic,2.msg38901.html#msg38901

Fast forward 2 years and what ever became of those diagrams? They'd sure come in real handy for my GD-44 3d project...Orionblamblam said:Some greatly reduced (15% of original size) snips of some Convair Model 44 diagrams I came across. The full-rez, complete versions of these may or may not wind up for sale, but for now the full rez versions are "embargoed."

Admiral Connolly: I would like to answer your question this way Mr. Price, by saying the VFX-2 is the VFAX. We would not produce another plane.

Source: The Pentagon Paradox. The development of the F-18 Hornet” by James Perry Stevenson (ISBN 1557507759), Shrewsbury, 1993"On 19 June, 1973, Deputy Secretary of Defence Clements, proposed a fly-off

between a nasalized version of the F-15 Eagle, which he designated the 'F-15N',

and a light-weight version of the Grumman F-14 Tomcat (one without 1,000 to

1,300 pounds of AIM-54 Phoenix missile avionics), which he called the 'F-14D'.

Clements proposed building two copies of each airplane at a cost of $250

million. Even though he proposed taking the funds from other Navy programs, the

Navy supported this prototype program - officially.

A month latter, based on Spangenberg's claim that the cost would not be

$250 million, as Clements said, but $367.8 million for the four aircraft, the

Senate Tactical Air subcommittee rejected Clements's idea as too

expensive"

MANDATED COMMONALITY: NAVY AIR COMBAT FIGHTER

Competitive prototyping has since been embraced verbally by vira.

ttlly everyone concerned with the weapon systems procurement process,

and of course it has also been put into use 'though rarely extended

into the full-scale development phase). The first two post-1966 programs

to feature competitive prototypes, the Air Force's A-X and Lightweight

Fighter (LWF) programs, have been subjected to some preliminary

analysis at Rand and elsewhere. More interesting in the context of

this report is the Navy's search for a lightweight, low-mix tactical

aircraft.

The outstanding characteristic of Congress's role in what has become

the F-18/A-18 program is its insistence on a course of action that

has necessarily restricted competition for the contract award. The

insistence has taken the form of denial of Navy requests for funding

of new design competitions of its own and attempted consolidation of

the Air Force and Navy efforts to arrest their declining inventories

of fighter aircraft. Specifically, the report of the conference committee

on the FY 1975 DoD Appropriation Bill contained this directive:

The Managers are in agreement on the appropriation of $20,000,000

as proposed by the Senate instead of no funding as proposed by the

House for the VFAX aircraft. The conferees support the need for

a lower cost alternative fighter to complement the [Navy's] F-14A

and replace F-4 and A-7 aircraft; however the conferees direct

that the development of this aircraft make maximum use of the Air

Force Lightweight Fighter and Air Combat Fighter technology and

hardware. The $20,000,000 provided is to be placed in a new program

element titled "Navy Air Combat Fighter" rather than VFAX.

Adaptation of the [yet-to-be] selected Air Force Air Combat Fighter

to be capable of carrier operations is the prerequisite for use

of the funds provided. Funds may be released to a contractor for

the purpose of designing the modifications required for Navy use.

Future funding is to be contingent upon the capability of the

Navy to produce a derivative of the selected Air Force Air Combat

Fighter design.

This section examines this episode by pinpointing the times when competition

might have been considered and identifying the considerations

that militated against its use.

The Navy's air superiority, combat air patrol, and intercept roles

are performed by the F-14 Tomcat. The high cost of the F-14A and its

Phoenix weapon system contributed to (and then in turn was exacerbated

by) contractual difficulties with the prime contractor (Grumman Corp.)

and stimulated the Navy's search for a low-cost fighter to bolster its

declining force level. In 1973, Deputy Secretary of Defense William

P. Clements proposed that prototypes of a stripped-down F-14A (called

the F-14X), a Navy version of the F-15 Eagle (designated the F-15N),

and a stripped F-4 Phantom be developed as possible alternatives to

follow-on F-14s. This proposal, involving an initial request of $150

million and a total cost of either $250 million (the estimate of Secretary

Clements) or over $367 million (the estimate of George A. Spangenberg),

was denied by the Senate Armed Services Committee as "too

costly and of questionable value." A committee statement accompanying

the FY 1974 DoD Appropriation Authorization Bill when it was reported

to the Senate floor read:

The committee believes the Navy should examine the potential of a

completely new aircraft as a possible alternative to the F-14 in

the out-years. The Navy should obtain proposals to determine if

a smaller and presumably cheaper aircraft can be designed to serve

as an air superiority fighter to complement the F-14. Once this

determination has been made, the committee desires to receive the

Navy determination, including the costs of such alternatives as

well as a technical evaluation.

Competition in the Acquisition of Major Weapon Systems:

Legislative Perspectives

November 1976

Michael D. Rich

F-15N "Sea Eagle"

Last revised March 4, 2000

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

During the development phase of the Eagle, the US Navy was instructed in July of 1971 to take a look at a possible navalized version of the Eagle, provisionally designated F-15N. At that time, the Navy was perfectly happy with its Grumman F-14A Tomcat, which was then in its flight test phase, and was less than enthusiastic about a "Sea Eagle".

The navalized F-15N was estimated to weigh some 2300 pounds more than the USAF F-15A. The Navy was unhappy about the fact that the F-15N aircraft would be unable to carry or launch the AIM-54A Phoenix long-range missile. Inclusion of this missile would have increased the weight even further. Consequently, the F-15N proceeded no further than the concept stage.

The US Senate briefly revived the carrier-based Eagle idea in March of 1973. However, the Navy decided instead to go with a mix of F-14 Tomcats and F/A-18 Hornets, and the F-15N was never ordered.

Sources:

McDonnell Douglas Aircraft Since 1920, Volume II, Rene J. Francillon, Naval Institute Press, 1990.

Combat Aircraft F-15, Michael J. Gething and Paul Crickmore, Crescent Books, 1992.

The American Fighter, Enzo Angelucci and Peter Bowers, Orion, 1987.

F-15 Eagle, Robert F. Dorr, World Airpower Journal, Volume 9, Summer 1992.

F-14D said:I'd like to throw out a few thoughts here,, for what they're worth. Since they touch on so many posts, and I'm not that good at splicing in multiple quotes, I'll just fire away:

1. F-15N operating an Essex (actually Ticonderoga class), while F-4 and F-14 couldn't, according to McAir. Well, of course they'd say that. In point of fact, the F-14 had a requirement to operate from those same carriers as well; that was the reason for its very low approach speed. However, that requirement was dropped because a) the Gov't failed to deliver an engine of the specified thrust and weight that made it feasible. b) It was clear in the early '70s that this class of carrier wasn't going to be with us for many more years anyway, so it wasn't worth the trouble and expense to have this capability. There was also the issue with both aircraft of the "Yellow Gear" on such a small carrier.

2. F401 dying through lack of funding. Technically correct, but there's more to it than that. The Air Force at this time was encountering developmental problems with the F100. Reliability in the test program was not up to snuff and the engine was not taking well to rapid changes in fuel flow. The F100 engine at this point in time was more critical to USAF than the F401 was to the Navy. Although the F401 was the engine around which the F-14 was designed and provided the thrust levels and sfc benefits to allow the F-14 to meet its design specifications, the Tomcat was flying successfully with the TF30. Without the F100, though, there could be no F-15. USAF knew that given enough time they would solve the early F100 problems. In fact, they eventually did in the next decade (partly by derating the engine), but at this juncture it didn't look like Congress was going to give them the necessary time. One of the most critical tests was the 150 hour run, wherein an F100 would have to run for 150 hours without failing. Congress had made it clear that without passing this test funding for the F100 would disappear, and the Eagle would remain grounded. Published reports at the time were somewhat confusing about the definitive 150 qualification test. According to some reports, on the critical test the engine was closely monitored and if certain key components appeared that they were about to fail, the test was suspended, the component replaced, and then continued. The F100 engine passed the test. Once the F100 passed the 150 hour qualification test the Air Force was no longer responsible for reliability and endurance improvements in the common core. At this point the Navy was on its own, and had to accept the core in its current state. Any desired core improvements would have to be funded solely by the Navy. The Navy took a look at what it would cost to bring the core up to an acceptable level of reliability and performance to bring the F401 into service and decided it just wasn't worth it, and so abandoned the engine in April, 1974. It wasn't until the arrival of the F110 that the Tomcat got the engine around which the plane had been designed. It has also been said that it wasn't until the arrival of the F110 that Pratt got serious about improving the F100's reliability and performance.

3. F-15N vs F-14 wing loading. It appears when deriving those numbers, you used the figure of 565 ft2 for the lifting area of the Tomcat. This ignores the entire tunnel area, which is a lifting body that adds 443 ft2 once the wings sweep. Using the full lifting area would give a ratio of 68, not 122 for the F-14 vs 94 for the F-15. This is one of the reasons that an F-14 at comparable T/W ratios outturned the F-15 (unless the TF30s were acting up in the F-14, unless the F100s were acting up in the F-15).

4. F-15 doing a loop at 150 knots IAS. Yes, it probably can, under the right conditions and at a safe altitude, but keep in mind that going up it’s under full a/b, not a normal condition on approach, and on the other half it’s going down rapidly, also something you probably wouldn’t want to do with the ocean filling your windscreen. The ability to do this would really have no relevance to landing on a carrier, as would a stalling speed that’s partly achievable due to downward thrust at extreme AoAs.

5. F-15N itself. Without massively redoing the wing and control surfaces I would find it hard to believe that the -15N would have an approach speed of 120 knots. Keep in mind the even the “light” F/A-18A, which was designed to be carrier compatible from the get-go can’t do that. Also, you have to keep the nose where you can see the MLS and deck. Lots of a/c can fly really slow if you point th nose at the stars. F-14 is something like 45 knots. Hey, the Mig-29 and SU-27 can do zero! In any case, the original impetus for the -15N was a push by McAir to try and sell more of their planes (can’t blame them). The “flyoff” idea was never serious, IMHO, but a way to placate Congress. It would cost a fortune to do, and while valuable would only mostly tell you what you already knew. ,Just assume that both planes would do what their manufacturers promised. What do you learn? Actually, there was sort of a “flyoff” once-the second Iranian fighter order (under the Shah). Both the F-15 and F-14 were involved. The F-15 flew first and gave its usual eye-watering performance and there were some really neat shots of it making its really tight turns as it headed back onto the base for the next maneuver. The F-14 flew next, and essentially matched the Eagle’s performance (with couple of extras thrown in), with one notable difference: it was able to do all that within the airfield’s perimeter. This was a contributing, but not the only factor in why Iran bought the F-14 on both buys. As an aside, one of the big reasons there weren’t more F-14 export orders is that except for Iran, the US wouldn’t allow the aircraft to be exported (although they probably would have made an exception of the UK).

In any case, in order for the F-15N to be a viable concept the Navy would have to relax its requirements to whatever the -15N was capable of (shades of the Hornet!). Range and endurance, sensor performance, etc. . Because of the funding issues (mostly caused by the Gov’t) the F-15N was at least considered, but what really doomed the idea was that it would have cost more to “navalize” and equip the Eagle for the Navy than the amount of the funding issues with the F-14, and you would have ended up with a less capable, less versatile aircraft. No reflection on the Eagle, just that’s why the Tomcat cost more (along with production rates). Also, there was really no need to take on a new aircraft with a more expensive, unreliable engine when the Navy already had a less-expensive unreliable engine of its own.

Because of this and due to massive and effective lobbying by the light fighter lobby, it was decided to develop a “Naval Air Combat Fighter”, as the Air Force was doing because of pressure over the cost of the F-15. Not too far into that, Congress weighed in and decreed that the NACF would be required to be a derivative of the USAF’s ACF.

F-14D said:zen said:The F-15N was rated by McAir as suitable for down to CVA-19 (Essex) carriers which the F-4 and F-14 weren’t.

Wow!

No mean feat if true.

Does this mean a dry thrust launch?

And one wonders about recovery of any large, heavy and fast aircraft on such short angled decks as on the modernised Essex types.

Has someone mentioned TO and L speed for this F15N?

In order to operate from a Essex/Ticonderoga, the launch would have to be dry thrust or minimum a/b because if nothing else the flame arrestors on the catapults couldn't handle what came out of the back of the jet at max a/b. On the Forrestal and later CVs, the arrestors were modified to be water cooled for the F-14, so the problem would be even more for a higher thrust engine. There wasn't room in the Ticonderogas, I believe, for this gear. The idea for the smaller carriers was that you would never go off the deck on a Ticonderoga with four + AIM-54s, it would be an AIM-7/AIM-9 loadout. The was intended to have as much thrust a military power as the TF30 did in max a/b, and that's how the goal would be achieved. When the F401 died, that dram tically impacted the ability to operate from the smaller carriers. Even though it was lighter, I'm not sure you could have gotten an F-15N off the deck except with a dramatically reduced payload without using a/b, even if you could have gotten it on the deck.

BTW, an F/A-18 couldn't operate from those smaller carriers either.

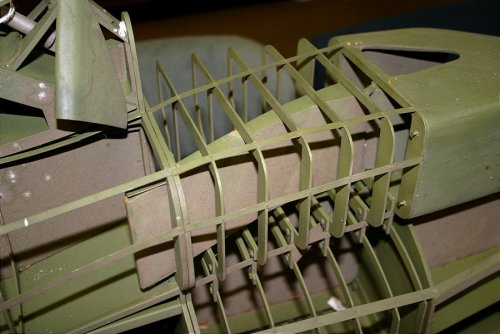

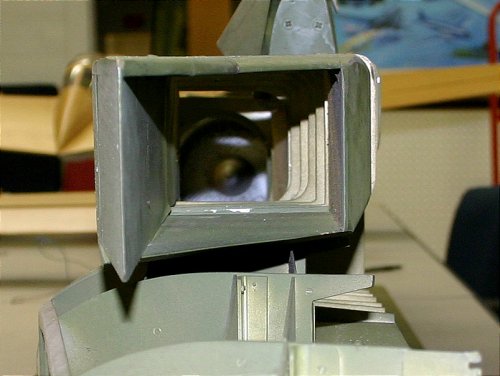

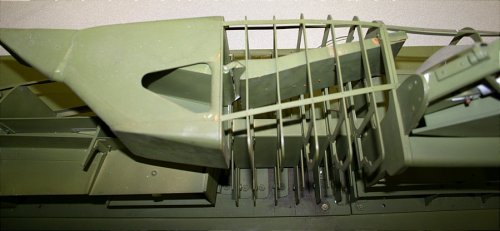

PaulMM (Overscan) said:Seems expensive for a reasonably small and crude model, but I guess its worth what someone will pay.

PaulMM (Overscan) said:It might be something like these deck spotting models - size and level of detail is comparable I think. This model for sale has folding tailplanes I think?