Cost Worries Could Derail Plan for Next Bomber to Be Unmanned: U.S. General

May 10, 2012 By Elaine M. Grossman Global Security Newswire

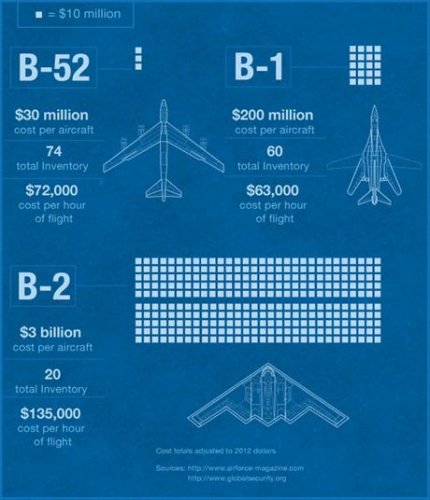

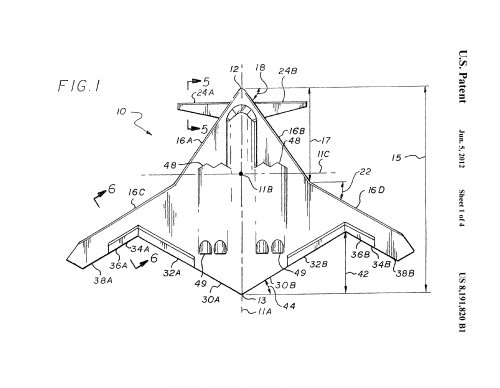

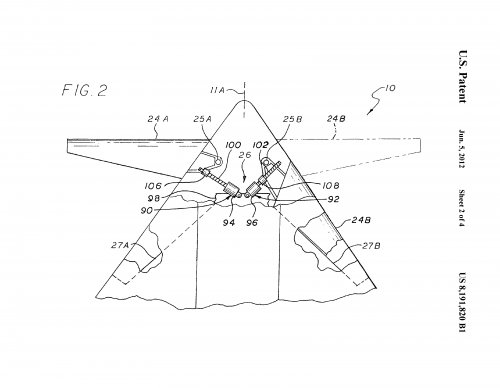

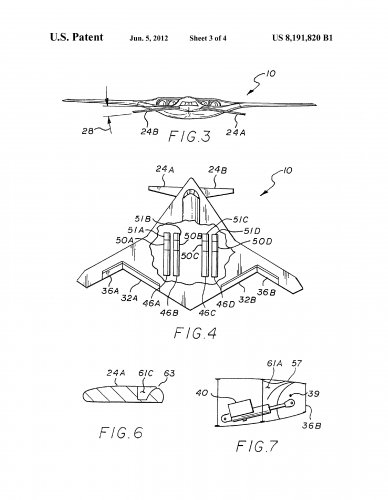

A U.S. B-2 strategic bomber, shown in January. Building an unmanned version of a future bomber aircraft could be unaffordable, the head of Air Force Global Strike Command signaled on Thursday (AP Photo/Mark Terrill). WASHINGTON -- Making the nation’s future bomber aircraft capable of flying by remote control could prove unaffordable, a senior U.S. Air Force general said on Thursday (see

GSN, April 26). Cost considerations are “probably going to make it difficult to afford an unmanned solution up front,” Lt. Gen. James Kowalski, who heads the Air Force Global Strike Command, told a breakfast event audience on Capitol Hill. “I think that would be a real challenge for industry.” This was a surprising revelation about a planned key feature of the Air Force’s top-priority, new weapon system: the ability for a Long Range Strike aircraft to be “optionally manned,” flying either with or without a pilot in the cockpit.

Defense Department leaders have imposed a $550-million-per-unit cost cap on the service’s next-generation stealth bomber, which is to be capable of operating inside hotly contested enemy airspace. The price ceiling is part of a broader effort to curb long-term military spending. The Air Force’s top officer, Gen. Norton Schwartz, has said his service understands that if the new bomber exceeds the half-a-billion-dollar price tag, the program risks being canceled (see

GSN, March 1). The first such aircraft is to be fielded during the 2020s, according to the service. “Right now we’re going through that process of determining [the bomber’s required performance] parameters,” Kowalski said. “I think what we will discover is that [cost] may, in fact, be what drives us in terms of the trade space on manned and unmanned [capability].” For years, the Air Force resisted embracing unmanned aircraft, preferring instead the extra measure of awareness and control that pilots might bring to the cockpit. Service leaders have since warmed to the benefits offered by remotely piloted drones, particularly given the central role these aircraft have come to play in gathering intelligence and targeting extremists abroad. “That’s a great idea if you want to save some money up front,” Hans Kristensen, who heads the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Program, said of the Air Force move to reconsider a pilotless version of the bomber. “There’s no doubt it would cost more to have both pilots and unmanned -- you have double capability.” If the Air Force must choose between a manned or unmanned version of the bomber, it is no surprise that it would opt for maintaining a capacity for pilots onboard, he said.

“There are just too many missions for which it would be inconceivable to kick the pilot out of the cockpit, nuclear delivery being one of them,” Kristensen said. One long-valued benefit to a nuclear-armed bomber is that, unlike a missile, it could be recalled while en route to its target; a preprogrammed drone, by contrast, could potentially diminish the role of human judgment or control. Not every issue expert supports this potential scaling back of the bomber’s capabilities. Baker Spring, a national security policy research fellow at the Heritage Foundation, called a manned-only Long Range Strike bomber a “bad idea.” “The Air Force should be permitted to explore the full range of options,” he told

Global Security Newswire. “This points out why the Obama administration’s projected defense budgets, even absent sequestration, are inadequate.” The 2011 Budget Control Act mandates a roughly $450 billion cut in defense spending over the next decade. That amount could more than double under the sequester process if lawmakers do not by the end of this year reverse the legislation’s demand for $1.2 trillion in additional government-wide reductions. For the bomber aircraft, Spring speculated that the “cost of exploring the option of an unmanned version could be relatively modest. Under certain circumstances, I could see it adding less than 2 percent to the total acquisition cost for the program.” Air Force officials have not said how expensive the overall program might be or how many aircraft they would seek to buy. Based on the per-plane cost limit, Spring estimated that the price to procure 100 of the new bombers could run roughly $50 billion. “Anybody who thinks that’ll be the final price is going to be very surprised,” Kristensen opined. Kowalski, whose Louisiana-based command oversees nuclear-capable bombers and ICBMs, also defended his service’s decision to certify the future bomber first for conventional operations, and only later allow the aircraft to deliver nuclear munitions.

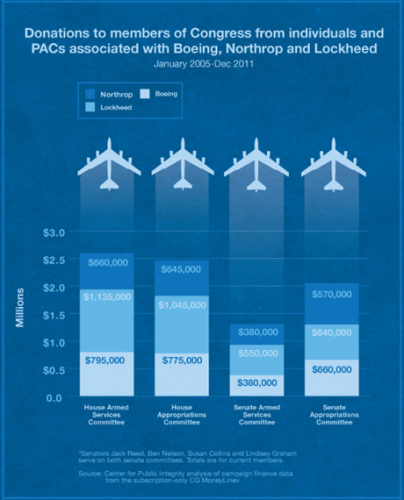

The House Armed Services Committee this week prepared a fiscal 2013 defense authorization

bill for debate on the chamber floor that would instead require the nuclear-capable bomber to gain Defense Department certification for potential use in atomic combat upon initial fielding. Kowalski said this would be a more expensive path and could delay getting a vital conventional capability in hand.

“If you look back at the history of our bombers … none of them came off [production lines] and were certified in both nuclear and conventional” missions when first introduced into the fleet, even during the Cold War, the three-star general said. “I don’t think it’s unreasonable to say, ‘Well, if we’re going to have it come off the line and be certified in one or the other first, what is probably the most pressing?’” said Kowalski. “I look at the range of military operations that the combatant commanders want, and I say probably conventional is the most pressing.”