tRY SEARCHING UNDER naca 1958 SPACECRAFT DESIGNS.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

US Lifting Bodies Studies - START (ASSET/PRIME), FDL, X-24, etc.

- Thread starter Archibald

- Start date

archipeppe

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 18 October 2007

- Messages

- 2,427

- Reaction score

- 3,119

flateric said:Another FDL-5 mock-up pic

Wonderful!!

This shot is really UNSEEN to me!!

Many thanks flat....

- Joined

- 27 May 2007

- Messages

- 676

- Reaction score

- 43

archipeppe said:flateric said:Another FDL-5 mock-up pic

Wonderful!!

This shot is really UNSEEN to me!!

Many thanks flat....

How long before this makes rounds and ends up with some people thinking it is a real craft?

airrocket

Dreams To Reality

awesome

Just came across a folder of stuff I printed off of Astronautix.com back in 2001 before I had a computer at home. I looked through it and thought I'd double check to see if the stuff had been updated but strangely there was a lot I couldn't find (big site though it could be buried somewhere there?!) So I've scanned the images and here they are...

Regards,

Barry

Regards,

Barry

Attachments

- Joined

- 13 August 2007

- Messages

- 8,367

- Reaction score

- 10,750

note the last picture is a fake from Internet

this Gemini "lifting body" is model after ASSET

this Gemini "lifting body" is model after ASSET

So that's why it disappeared :

Chiz for that.

Barry

Chiz for that.

Barry

antigravite

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 25 April 2008

- Messages

- 836

- Reaction score

- 258

hesham said:Hi,

unknown lift body.

*Not* unknown. That's Martin's Dyna Soar entry, as designed by Hans Multhop.

Attachments

- Joined

- 26 May 2006

- Messages

- 34,685

- Reaction score

- 15,517

XP67_Moonbat

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 16 January 2008

- Messages

- 2,268

- Reaction score

- 524

Good call. I was just going to remark that Bill Rose's book shows it being Lockheed's 301 for the X-24C.

- Joined

- 1 April 2006

- Messages

- 11,337

- Reaction score

- 9,981

This is (un)complete zoo of NASA Langley hypersonic research aircrafts studied.

'Figure shows four of the prinicipal configurations that were tested[..].

Structures, thermal protection, scramjet engine integration and aerodynamic performance

across the speed range were among the requirements which shaped each configuration.

The configurations are shown in the chronological order in which they were conceived

but do not necessarily reflect continuing trends in design.

The first and third configurations were generated in-house at Langley, while the second

was heavily influenced by cooperation with the Air Force X-24C program (Martin Marietta X-24C? - Flat.).

The fourth configuration was generated by a contractor to provide an alternate approach (Lockheed X-24C - L-301?- Flat.) (an additional alternate approach was also generated by a contractor under Air Force sponsorship (Rockwell HYTID - Flat.)

The first , third , and fourth configurations are airplane - like in character, whereas the second has features more in common with a high cross-range reentry vehicle. Although similar in overall design and purpose, these four configurations provided quite different problems from a fluid dynamic and heating standpoint."

Source

AIAA-81-1145

A survey of heating and turbulent boundary layer characteristics of several hypersonic research aircraft configurations

LAWING, P. L., NASA, Langley Research Center, Transonic Aerodynamics Div., Hampton, VA

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Thermophysics Conference, 16th, Palo Alto, CA, June 23-25, 1981

'Figure shows four of the prinicipal configurations that were tested[..].

Structures, thermal protection, scramjet engine integration and aerodynamic performance

across the speed range were among the requirements which shaped each configuration.

The configurations are shown in the chronological order in which they were conceived

but do not necessarily reflect continuing trends in design.

The first and third configurations were generated in-house at Langley, while the second

was heavily influenced by cooperation with the Air Force X-24C program (Martin Marietta X-24C? - Flat.).

The fourth configuration was generated by a contractor to provide an alternate approach (Lockheed X-24C - L-301?- Flat.) (an additional alternate approach was also generated by a contractor under Air Force sponsorship (Rockwell HYTID - Flat.)

The first , third , and fourth configurations are airplane - like in character, whereas the second has features more in common with a high cross-range reentry vehicle. Although similar in overall design and purpose, these four configurations provided quite different problems from a fluid dynamic and heating standpoint."

Source

AIAA-81-1145

A survey of heating and turbulent boundary layer characteristics of several hypersonic research aircraft configurations

LAWING, P. L., NASA, Langley Research Center, Transonic Aerodynamics Div., Hampton, VA

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Thermophysics Conference, 16th, Palo Alto, CA, June 23-25, 1981

Attachments

- Joined

- 1 April 2006

- Messages

- 11,337

- Reaction score

- 9,981

Following is excerpt from a beautiful paper by Curtis Peebles

"The X-43A Flight Research Program: Lessons Learned on the Road to Mach 10"

(full-text document available here http://hdl.handle.net/2060/20070021686)

Chapter gives quite an clear timeline of hypersonic projects considered by NASA and DoD in 1970s

I've added links to various programs already depicted at SPF to make a picture wider.

NHFRF

The development of the airframe-integrated scramjet came at a time of little

interest in such advanced concepts. The 1970s saw the end of NASA’s Apollo program,

and a halt in U.S. manned spaceflights for half a decade. The unmanned planetary

missions approved in the late 1960s and early 1970s were launched, but proposed

advanced follow-on flights failed to gain approval.

Aeronautical research experienced a similar decline. The X-15 program ended in

1968. The lifting body program was still under way in the early 1970s, with research

flights by the HL-10, X-24A, and M2-F3 vehicles, but its end was approaching. The final

lifting body was the X-24B. This was actually the X-24A fitted with a modified longnose

delta fuselage. This shape had two applications. It gave a better cross-range

capability to a vehicle re-entering from orbit, and could also be used by a hypersonic

cruise vehicle powered by advanced air-breathing engines. Flight tests of the X-24B

began in 1973 and ended in 1975; bring the lifting body program to a close.

The end of the X-15 research and the winding down of the lifting body programs

left a void in aeronautical research. The development of a new hypersonic vehicle had

wide appeal within both the Air Force and NASA. In 1972 the Air Force Flight Dynamics

Laboratory (FDL) proposed delta-wing test vehicle that would fly at speeds between

Mach 3 to 5. The following year, the FDL offered a plan for an Incremental Growth

Vehicle, so named because it would initially fly at Mach 4.5, but then be upgraded to

reach Mach 6, and finally Mach 9. At the same time, Langley Research Center engineers

had ideas of their own. Their initial vehicle concept was the Hypersonic Research Facility

(HYFAC) which was designed to reach a top speed of Mach 12 – twice the X-15’s

maximum speed. This was followed in 1974 by a proposal for a less exotic vehicle, called

the High-Speed Research Aircraft (HSRA), with a top speed of Mach 8.

All of the FDL and NASA proposed concept vehicles had provisions for testing of

air-breathing propulsion systems. The proposals differed in their research goals, however.

The FDL vehicles focused on designs that would be suitable for military roles such as

interception, reconnaissance, or strike. The NASA proposals were for long-range

hypersonic cruise vehicles and space launchers. None of the concepts received official

support to begin development.

This nearly changed with another FDL proposal, which overlapped the more

advanced concepts. At about the time the X-24B made its first flights, the FDL engineers,

who had developed the X-24B shape, began studying a hypersonic version called the “X-

24C.” Two different vehicle concepts were proposed – one with cheek inlets for an airbreathing

engine, and a second powered by an XLR-99 rocket engine. The target speed

would be Mach 5. X-24C program costs were estimated to be around $70 million.

The advantage of the X-24C proposal was that it was largely an “off-the-shelf”

design in terms of shape, equipment, and technology. This made it a much more practical

design than the more complex FDL and NASA proposals. The X-24C gained the support

of Gen. Sam Phillips, the head of the Air Force Systems Command and a former senior

official in the Apollo program.

Both the X-15 and lifting body programs had been run as joint NASA/Air Force

efforts, so it made sense to do the same for the emerging X-24C. In December 1975, a

month after the final X-24B flight, NASA and the Air Force formed an X-24C Joint

Steering Committee. This consisted of the commanders of the Air Force Flight Test

Center and the FDL, and the directors of NASA’s Flight Test Center (now Dryden Flight

Research Center) and Langley Research Center.

Over the next several months, the group moved away from the relatively simple

X-24C concept, toward the larger, more complex vehicles proposed by Langley and the

FDL. The rationale was that a joint NASA/Air Force “research facility” should be

designed to undertake research into a wide range of “pacing technology” in hypersonic

flight, and serve as a focus for U.S. research efforts in the field. This, planners

envisioned, would combine a wide range of research goals into a single vehicle.

The Air Force wanted to test military-related technology experiments –

photography, weapons separation, radome heating, nose tip erosion, thermal protective

systems, and removable fins. Different air-breathing propulsion systems were to be

tested, including integrated rocket ramjets, as well as subsonic combustion ramjets. To do

this, designers moved away from the X-24C shape, toward a design more akin to those of

the Langley concepts. The vehicle would have a modular configuration, with a removable

center section of the fuselage, to accommodate the different experiments. With the

connection to the original X-24C vehicle now gone, the program received a new name.

The traditional X-plane designation was abandoned and replaced with the awkward

“National Hypersonic Flight Research Facility,” (NHFRF, but pronounced “nerf”).

The proposed NHFRF gained favor within NASA, as it fulfilled a number of

research and institutional needs. For the NASA Flight Research Center, the X-24C was a

continuation of the previous three decades of research into high-speed flight, revitalized

the role of aeronautics within NASA, and provided a major role for the center during the

Shuttle era. For Langley aeronautical and propulsion engineers, the vehicle was the

culmination of all their efforts in high-speed flight and air-breathing propulsion system.

They also saw it as a means to “cover the whole hypersonic waterfront and do it before

we’ve lost all the hypersonic talent we developed from the X-15 program.”

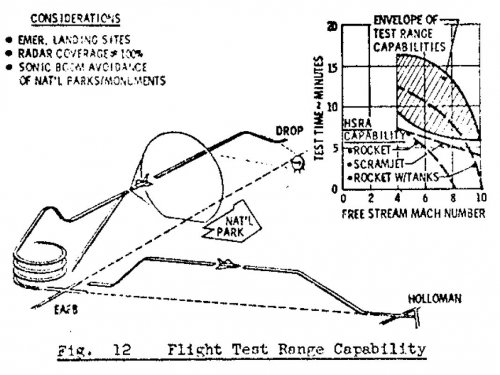

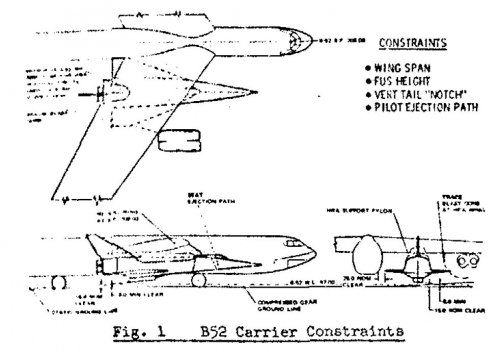

The planned performance of the NHFRF was impressive. After launch from the

B-52B mothership, the vehicle could reach a maximum speed of Mach 8 under rocket

power. It also was designed to cruise at a speed of Mach 6+ for 40 seconds. This was an

extremely demanding requirement. The project engineers envisioned construction of two

NHFRF vehicles, to be used in a 200-flight research program beginning in 1983, and

spanning a decade. This effort was estimated to cost $200 million.

Despite the support for the NHFRF by both NASA and the Air Force, however,

trouble for the project was ahead. Much of NASA’s budget was committed to the Space

Shuttle, and both technical problems and high inflation were causing the program’s costs

to balloon. At the same time, the Air Force was introducing a new generation of fighter

aircraft, against a background of funding cutbacks and poor morale. The increasing

complexity of the NHFRF had, by early 1977, raised the estimated cost to as much as

$500 to $600 million. NASA Headquarters was unwilling to foot the ever-growing bill,

and in September 1977 cancelled the agency’s participation in the project. James J.

Kramer, the acting NASA associate administrator for aeronautics and space technology,

stated that, “the combination of a tight budget and the inability to identify a pressing

near-term need for the flight facility had led to a decision by NASA not to proceed to a

flight test vehicle at this time.” The Air Force could not take over full funding of the

NHFRF, and ended its support for the effort.

Although the X-24B was the last rocket-powered research aircraft to fly, it was

the failure of the X-24C/NHFRF to receive approval that ended the thirty-year era of

rocket planes, flying to ever higher speeds and altitudes. The era had begun in 1946 with

the glide flights of the X-1, in a blaze of publicity. The era ended with a memo, and its

passing went unnoticed. The end of NHFRF dealt a hard blow to morale at the Flight

Research Center, and recriminations soon followed. Some blamed over-management.

Objections were also raised about the 40-second cruise requirement. This added

considerable cost and difficulty to development of the NHFRF. Some argued it would

have been better to build the original X-24C design rather than a more advanced and

complex vehicle designed to be all things to all people.

In retrospect, it seems unlikely that even the original X-24C concept would have

been approved. The reasons were not technical, as with the Aerospaceplane. There would

certainly have been difficulties and setbacks, especially with the more complex NHFRF

concepts, but engineers could have drawn on the technology and experience from the X-

15 and lifting body programs in solving those difficulties. The real problem preventing

the project from gaining support was that the time was simply not right for a project like

the X-24C/NHFRF. At the time, the research focus at NASA was shifting to such projects

as supercritical wing designs, winglets, and digital-fly-by-wire. While a scramjetpowered

vehicle could serve as a second-generation space vehicle, the Space Shuttle had

yet to fly; it was far too early to begin work on a replacement. Finally, the “me

generation” mentality that marked the 1970s was unfavorable to the bold challenges of

flying at high speeds and altitudes that had so captivated engineers in the previous three

decades.

Among the lessons that can be drawn from the X-24C/NHFRF is that it is not

enough for a project to be technically feasible, and that its data would be valuable. As

with the NACA’s research activities, NASA aeronautical efforts were publicly funded

projects. They had to relate to national needs. The supercritical wing designs and

winglets both offered major improvements in fuel economy; a major public and

commercial issue in the wake of the sharp increase in fuel costs in the early 1970s. Flyby-

wire technology opened new possibilities in aircraft design, in that this removed the

need for an aircraft to be inherently stable.

Over the following decades, supercritical wings became standard on business jets,

airliners, fighters, and heavy transports. Winglets appeared on sailplanes, light aircraft,

business jets, airliners, and heavy transports. Virtually all new military and many airliners

built during this period used fly-by-wire control systems. In terms of the impact on

aeronautics, the government research funding provided for these areas was justified.

The “need for speed” and ever-higher altitudes, in contrast, which had been

driving forces in both civilian and military aircraft design, were no longer critical issues.

Supersonic Transports were uneconomical to operate due to high fuel prices. Strategic

bombers now flew at low level to strike their targets, while the emerging stealth

technology was incompatible with supersonic flight. The airliners, fighters, and bombers

built in the latter part of the 20th century all flew within the speed and altitude envelopes

of aircraft built during the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Beyond these public policy issues, another factor was the lack of focus in the

research goals for the X-24C/NHFRF. Trying to accomplish a wide range of goals made

the vehicle more complex, and the heritage from the X-24B shape and systems was lost.

This resulted in rapid cost increases even before the program was approved. In contrast,

with the X-15, the original research goals were limited to high-speed/high-altitude flight.

The vehicle had enough “stretch” built into it to later accommodate scientific and

engineering experiments.

As a result of the failure of the NHFRF to gain approval, nearly a decade would

pass before a major scramjet development effort would again be made. The new effort

was to be much more ambitious, but would still suffer from the same old flaws.

"The X-43A Flight Research Program: Lessons Learned on the Road to Mach 10"

(full-text document available here http://hdl.handle.net/2060/20070021686)

Chapter gives quite an clear timeline of hypersonic projects considered by NASA and DoD in 1970s

I've added links to various programs already depicted at SPF to make a picture wider.

NHFRF

The development of the airframe-integrated scramjet came at a time of little

interest in such advanced concepts. The 1970s saw the end of NASA’s Apollo program,

and a halt in U.S. manned spaceflights for half a decade. The unmanned planetary

missions approved in the late 1960s and early 1970s were launched, but proposed

advanced follow-on flights failed to gain approval.

Aeronautical research experienced a similar decline. The X-15 program ended in

1968. The lifting body program was still under way in the early 1970s, with research

flights by the HL-10, X-24A, and M2-F3 vehicles, but its end was approaching. The final

lifting body was the X-24B. This was actually the X-24A fitted with a modified longnose

delta fuselage. This shape had two applications. It gave a better cross-range

capability to a vehicle re-entering from orbit, and could also be used by a hypersonic

cruise vehicle powered by advanced air-breathing engines. Flight tests of the X-24B

began in 1973 and ended in 1975; bring the lifting body program to a close.

The end of the X-15 research and the winding down of the lifting body programs

left a void in aeronautical research. The development of a new hypersonic vehicle had

wide appeal within both the Air Force and NASA. In 1972 the Air Force Flight Dynamics

Laboratory (FDL) proposed delta-wing test vehicle that would fly at speeds between

Mach 3 to 5. The following year, the FDL offered a plan for an Incremental Growth

Vehicle, so named because it would initially fly at Mach 4.5, but then be upgraded to

reach Mach 6, and finally Mach 9. At the same time, Langley Research Center engineers

had ideas of their own. Their initial vehicle concept was the Hypersonic Research Facility

(HYFAC) which was designed to reach a top speed of Mach 12 – twice the X-15’s

maximum speed. This was followed in 1974 by a proposal for a less exotic vehicle, called

the High-Speed Research Aircraft (HSRA), with a top speed of Mach 8.

All of the FDL and NASA proposed concept vehicles had provisions for testing of

air-breathing propulsion systems. The proposals differed in their research goals, however.

The FDL vehicles focused on designs that would be suitable for military roles such as

interception, reconnaissance, or strike. The NASA proposals were for long-range

hypersonic cruise vehicles and space launchers. None of the concepts received official

support to begin development.

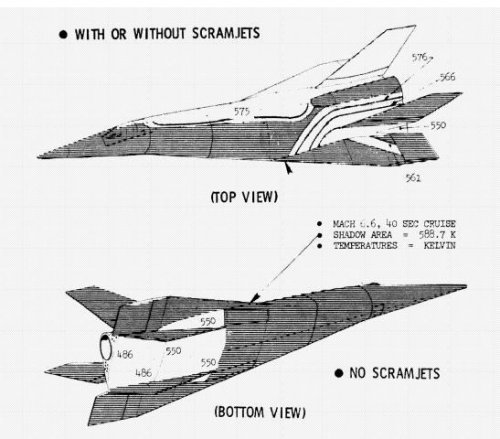

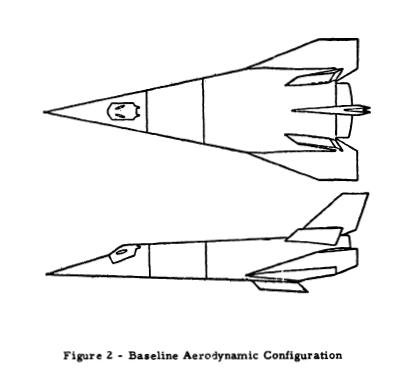

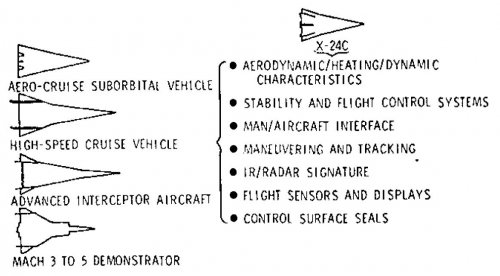

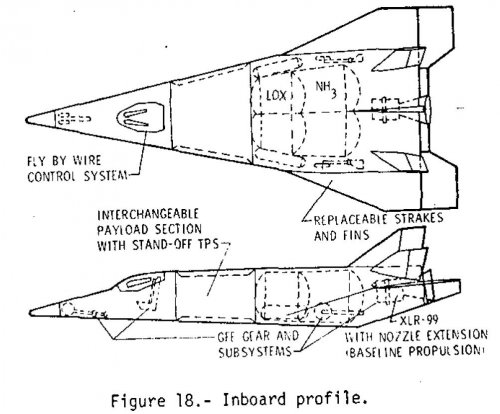

This nearly changed with another FDL proposal, which overlapped the more

advanced concepts. At about the time the X-24B made its first flights, the FDL engineers,

who had developed the X-24B shape, began studying a hypersonic version called the “X-

24C.” Two different vehicle concepts were proposed – one with cheek inlets for an airbreathing

engine, and a second powered by an XLR-99 rocket engine. The target speed

would be Mach 5. X-24C program costs were estimated to be around $70 million.

The advantage of the X-24C proposal was that it was largely an “off-the-shelf”

design in terms of shape, equipment, and technology. This made it a much more practical

design than the more complex FDL and NASA proposals. The X-24C gained the support

of Gen. Sam Phillips, the head of the Air Force Systems Command and a former senior

official in the Apollo program.

Both the X-15 and lifting body programs had been run as joint NASA/Air Force

efforts, so it made sense to do the same for the emerging X-24C. In December 1975, a

month after the final X-24B flight, NASA and the Air Force formed an X-24C Joint

Steering Committee. This consisted of the commanders of the Air Force Flight Test

Center and the FDL, and the directors of NASA’s Flight Test Center (now Dryden Flight

Research Center) and Langley Research Center.

Over the next several months, the group moved away from the relatively simple

X-24C concept, toward the larger, more complex vehicles proposed by Langley and the

FDL. The rationale was that a joint NASA/Air Force “research facility” should be

designed to undertake research into a wide range of “pacing technology” in hypersonic

flight, and serve as a focus for U.S. research efforts in the field. This, planners

envisioned, would combine a wide range of research goals into a single vehicle.

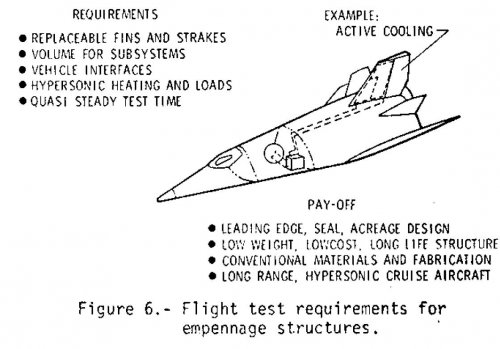

The Air Force wanted to test military-related technology experiments –

photography, weapons separation, radome heating, nose tip erosion, thermal protective

systems, and removable fins. Different air-breathing propulsion systems were to be

tested, including integrated rocket ramjets, as well as subsonic combustion ramjets. To do

this, designers moved away from the X-24C shape, toward a design more akin to those of

the Langley concepts. The vehicle would have a modular configuration, with a removable

center section of the fuselage, to accommodate the different experiments. With the

connection to the original X-24C vehicle now gone, the program received a new name.

The traditional X-plane designation was abandoned and replaced with the awkward

“National Hypersonic Flight Research Facility,” (NHFRF, but pronounced “nerf”).

The proposed NHFRF gained favor within NASA, as it fulfilled a number of

research and institutional needs. For the NASA Flight Research Center, the X-24C was a

continuation of the previous three decades of research into high-speed flight, revitalized

the role of aeronautics within NASA, and provided a major role for the center during the

Shuttle era. For Langley aeronautical and propulsion engineers, the vehicle was the

culmination of all their efforts in high-speed flight and air-breathing propulsion system.

They also saw it as a means to “cover the whole hypersonic waterfront and do it before

we’ve lost all the hypersonic talent we developed from the X-15 program.”

The planned performance of the NHFRF was impressive. After launch from the

B-52B mothership, the vehicle could reach a maximum speed of Mach 8 under rocket

power. It also was designed to cruise at a speed of Mach 6+ for 40 seconds. This was an

extremely demanding requirement. The project engineers envisioned construction of two

NHFRF vehicles, to be used in a 200-flight research program beginning in 1983, and

spanning a decade. This effort was estimated to cost $200 million.

Despite the support for the NHFRF by both NASA and the Air Force, however,

trouble for the project was ahead. Much of NASA’s budget was committed to the Space

Shuttle, and both technical problems and high inflation were causing the program’s costs

to balloon. At the same time, the Air Force was introducing a new generation of fighter

aircraft, against a background of funding cutbacks and poor morale. The increasing

complexity of the NHFRF had, by early 1977, raised the estimated cost to as much as

$500 to $600 million. NASA Headquarters was unwilling to foot the ever-growing bill,

and in September 1977 cancelled the agency’s participation in the project. James J.

Kramer, the acting NASA associate administrator for aeronautics and space technology,

stated that, “the combination of a tight budget and the inability to identify a pressing

near-term need for the flight facility had led to a decision by NASA not to proceed to a

flight test vehicle at this time.” The Air Force could not take over full funding of the

NHFRF, and ended its support for the effort.

Although the X-24B was the last rocket-powered research aircraft to fly, it was

the failure of the X-24C/NHFRF to receive approval that ended the thirty-year era of

rocket planes, flying to ever higher speeds and altitudes. The era had begun in 1946 with

the glide flights of the X-1, in a blaze of publicity. The era ended with a memo, and its

passing went unnoticed. The end of NHFRF dealt a hard blow to morale at the Flight

Research Center, and recriminations soon followed. Some blamed over-management.

Objections were also raised about the 40-second cruise requirement. This added

considerable cost and difficulty to development of the NHFRF. Some argued it would

have been better to build the original X-24C design rather than a more advanced and

complex vehicle designed to be all things to all people.

In retrospect, it seems unlikely that even the original X-24C concept would have

been approved. The reasons were not technical, as with the Aerospaceplane. There would

certainly have been difficulties and setbacks, especially with the more complex NHFRF

concepts, but engineers could have drawn on the technology and experience from the X-

15 and lifting body programs in solving those difficulties. The real problem preventing

the project from gaining support was that the time was simply not right for a project like

the X-24C/NHFRF. At the time, the research focus at NASA was shifting to such projects

as supercritical wing designs, winglets, and digital-fly-by-wire. While a scramjetpowered

vehicle could serve as a second-generation space vehicle, the Space Shuttle had

yet to fly; it was far too early to begin work on a replacement. Finally, the “me

generation” mentality that marked the 1970s was unfavorable to the bold challenges of

flying at high speeds and altitudes that had so captivated engineers in the previous three

decades.

Among the lessons that can be drawn from the X-24C/NHFRF is that it is not

enough for a project to be technically feasible, and that its data would be valuable. As

with the NACA’s research activities, NASA aeronautical efforts were publicly funded

projects. They had to relate to national needs. The supercritical wing designs and

winglets both offered major improvements in fuel economy; a major public and

commercial issue in the wake of the sharp increase in fuel costs in the early 1970s. Flyby-

wire technology opened new possibilities in aircraft design, in that this removed the

need for an aircraft to be inherently stable.

Over the following decades, supercritical wings became standard on business jets,

airliners, fighters, and heavy transports. Winglets appeared on sailplanes, light aircraft,

business jets, airliners, and heavy transports. Virtually all new military and many airliners

built during this period used fly-by-wire control systems. In terms of the impact on

aeronautics, the government research funding provided for these areas was justified.

The “need for speed” and ever-higher altitudes, in contrast, which had been

driving forces in both civilian and military aircraft design, were no longer critical issues.

Supersonic Transports were uneconomical to operate due to high fuel prices. Strategic

bombers now flew at low level to strike their targets, while the emerging stealth

technology was incompatible with supersonic flight. The airliners, fighters, and bombers

built in the latter part of the 20th century all flew within the speed and altitude envelopes

of aircraft built during the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Beyond these public policy issues, another factor was the lack of focus in the

research goals for the X-24C/NHFRF. Trying to accomplish a wide range of goals made

the vehicle more complex, and the heritage from the X-24B shape and systems was lost.

This resulted in rapid cost increases even before the program was approved. In contrast,

with the X-15, the original research goals were limited to high-speed/high-altitude flight.

The vehicle had enough “stretch” built into it to later accommodate scientific and

engineering experiments.

As a result of the failure of the NHFRF to gain approval, nearly a decade would

pass before a major scramjet development effort would again be made. The new effort

was to be much more ambitious, but would still suffer from the same old flaws.

- Joined

- 1 April 2006

- Messages

- 11,337

- Reaction score

- 9,981

As US flying bodies thread starts to look like weird zoo, I'll extract (a little bit later) all X-24C stuff in this separate thread as this craft deserves it's own one IMHO.

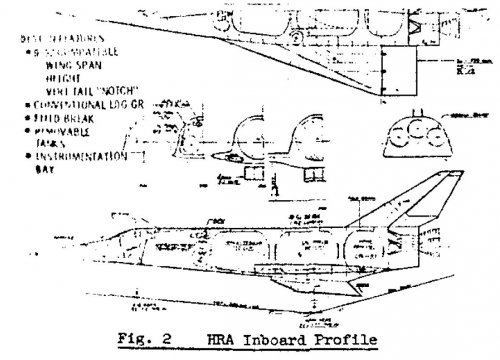

Following are early stages of X-24 evolution up to 1975 - from modified X-24B to something that have only common designation with the vehicle it have started its iterations. Main driving factors were wish to increase speed, sustain given Mach number at this speed for a certain amount of time (= to have appropriate aerodynamics, engine and fuel amount) and to place (in modular way) all the experiments that NASA and (mostly) USAF wanted to carry with the vehicle (including replacable payload section).

I still try to understand the difference between (early) Lockheed's and Martin's entry in X-24C (visible on factory desktop models are just difference in wing/empennage trailing edge). As I understand, Lockheed's X-24C-121 was an early entry, that later transformed to larger X-24C-L301, which already became an NHFRF (National Hypersonic Flight Research Facility).

Following are early stages of X-24 evolution up to 1975 - from modified X-24B to something that have only common designation with the vehicle it have started its iterations. Main driving factors were wish to increase speed, sustain given Mach number at this speed for a certain amount of time (= to have appropriate aerodynamics, engine and fuel amount) and to place (in modular way) all the experiments that NASA and (mostly) USAF wanted to carry with the vehicle (including replacable payload section).

I still try to understand the difference between (early) Lockheed's and Martin's entry in X-24C (visible on factory desktop models are just difference in wing/empennage trailing edge). As I understand, Lockheed's X-24C-121 was an early entry, that later transformed to larger X-24C-L301, which already became an NHFRF (National Hypersonic Flight Research Facility).

Attachments

- Joined

- 1 April 2006

- Messages

- 11,337

- Reaction score

- 9,981

- Joined

- 1 April 2006

- Messages

- 11,337

- Reaction score

- 9,981

This is Rockwell's HRA (Hypersonic Research Aircraft), as it goes from the schematics above, it was 1973 Mach 10 subscale prototype of HSRA.

Attachments

-

Rockwell_1974_HRA_7.jpg125.4 KB · Views: 194

Rockwell_1974_HRA_7.jpg125.4 KB · Views: 194 -

Rockwell_1974_HRA_6.jpg116.4 KB · Views: 216

Rockwell_1974_HRA_6.jpg116.4 KB · Views: 216 -

Rockwell_1974_HRA_5.jpg81.2 KB · Views: 199

Rockwell_1974_HRA_5.jpg81.2 KB · Views: 199 -

Rockwell_1974_HRA_4.jpg112.3 KB · Views: 180

Rockwell_1974_HRA_4.jpg112.3 KB · Views: 180 -

Rockwell_1974_HRA_3.jpg100 KB · Views: 192

Rockwell_1974_HRA_3.jpg100 KB · Views: 192 -

Rockwell_1974_HRA_2.jpg126.3 KB · Views: 204

Rockwell_1974_HRA_2.jpg126.3 KB · Views: 204 -

Rockwell_1974_HRA_1.jpg88.6 KB · Views: 227

Rockwell_1974_HRA_1.jpg88.6 KB · Views: 227

XP67_Moonbat

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 16 January 2008

- Messages

- 2,268

- Reaction score

- 524

I'd buy that for a dollar!

- Joined

- 17 October 2006

- Messages

- 2,393

- Reaction score

- 1,190

BB - Is that not an Isinglass configuration?

Al Draper headed the AF Flight Dynamics Lab post Sputnik. He and his team created ASSET, Model 122, BGRV and the FDL-1 to at least FDL-8 (X-24B). Al had proposed an FDL-7C/D hypersonic glider demonstrator as part of a USAF experimental aircraft program. NASA at the same time was proposing a scramjet demonstrator to congress. Congress is all its wisdom decided that since both flew at hypersonic speeds they could be merged. The result was NHFRT. A project the ruined the Earth circumferential glide of the FDL-7 and ruined the performance capability of a good scramjet design. Al battled hard to save the USAF position but in the end NASA's inability to limit the scope of any project and the impossible compromises imposed by forcing a hypersonic glider into the same moldlines as a scramjet cruiser were too hard to overcome and so overran the budget by that it was canceled.

McDonnell Douglas had a version of the FDL-7 called the Model 176 that was proposed as the support vehicle for the USAF MOL. When the USAF lost all space responsibility the Model 176 was also lost. 10 aircraft and 4 spares were designed to each fly 150 flights over a 15 year lifetime to average 10 flights per year, or a fleet rate of 100 flights per year. The MINIMUN flights to support the 24 person crew was 74.

McDonnell Douglas had a version of the FDL-7 called the Model 176 that was proposed as the support vehicle for the USAF MOL. When the USAF lost all space responsibility the Model 176 was also lost. 10 aircraft and 4 spares were designed to each fly 150 flights over a 15 year lifetime to average 10 flights per year, or a fleet rate of 100 flights per year. The MINIMUN flights to support the 24 person crew was 74.

Attachments

Woody said:That's fantastic Greg. Do you know more accurately which is which and whether any of them actually flew? I was always disappointed by how slow the HL-10 and X-24s were compared to the X-15, did any of this lot do any better?

Cheers, Woody

None of the subsonic glider experiments were designed to fly fast. All the full scale vehicle should have been capable of orbital reentry. Tjhe X-24C would have been a Mach 6 plus test bed. ASSET flew off a Thor booster in excess of 15,000 ft/sec.

Attachments

- Joined

- 1 April 2006

- Messages

- 11,337

- Reaction score

- 9,981

LowObservable said:BB - Is that not an Isinglass configuration?

Was Isinglass designed to be *so* fast?

Some years ago it was a federal offense just to speak or write Isinglass! Absolutely. One was a rocket boosted boost glide with circumferential glide range (about 22,500 ft/sec) and the other a Mach 12 cruiser. A model out of the past.flateric said:LowObservable said:BB - Is that not an Isinglass configuration?

Was Isinglass designed to be *so* fast?

Attachments

- Joined

- 1 April 2006

- Messages

- 11,337

- Reaction score

- 9,981

Well...we have started it about three years ago

http://www.secretprojects.co.uk/forum/index.php/topic,382.0/highlight,isinglass.html

http://www.secretprojects.co.uk/forum/index.php/topic,2867.0/highlight,paul+czysz.html

http://www.secretprojects.co.uk/forum/index.php/topic,382.0/highlight,isinglass.html

http://www.secretprojects.co.uk/forum/index.php/topic,2867.0/highlight,paul+czysz.html

XP67_Moonbat

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 16 January 2008

- Messages

- 2,268

- Reaction score

- 524

Ah, it's the good 'ol HGV again. Always cool.

XP67_Moonbat

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 16 January 2008

- Messages

- 2,268

- Reaction score

- 524

airrocket

Dreams To Reality

yes....FDL lifting body lives on.....

airrocket

Dreams To Reality

The 2D wedge insert is very much FDL and MCD tech. Its merely the FDL-7 shape with a 2D wedge inserted to add internal volume and or additional motors. I'll post the diagram when I have time to look it up. Note 2D has less drag than 3D a very good method to add volume without adding drag. Also instead of designing a new larger propulsion unit for every incremental size increase one merely adds the 2D wedge with more of same size propulsion units...= less development cost and time.

Similar threads

-

-

-

Secret Flight Test History - An Alternate History of the X-24C

- Started by Dynoman

- Replies: 27

-

-