Small Surface Combatant Task Force concepts

- Thread starter Triton

- Start date

- Joined

- 3 June 2006

- Messages

- 3,095

- Reaction score

- 3,972

Edit:

Wrongly, this post was first posted in the topic Littoral Combat Ship - Freedom/Independence

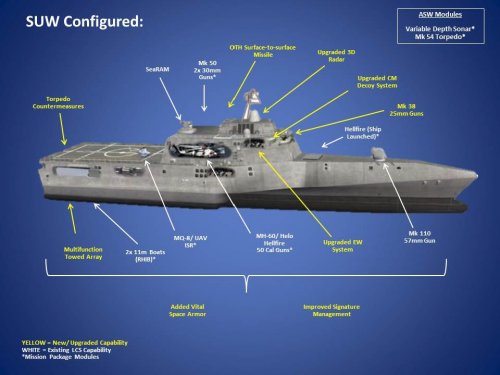

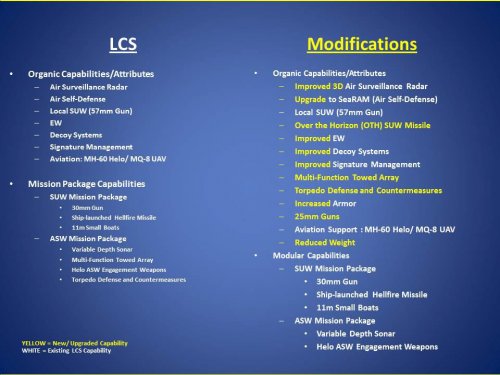

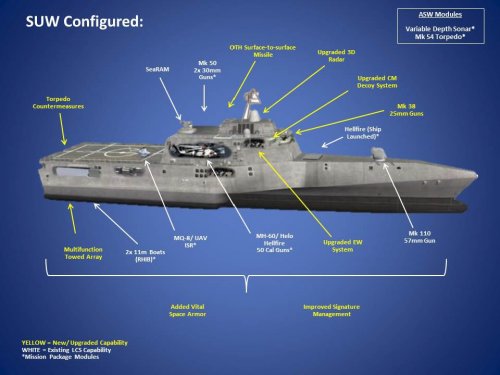

Looks like, the Navy wants that the LCS is changed from a corvette to a frigate.

Links:

http://intercepts.defensenews.com/2014/12/a-closer-look-at-the-modified-lcs/

http://www.defensenews.com/article/20141211/DEFREG02/312110041/Split-Decision-New-US-Navy-Ship

Wrongly, this post was first posted in the topic Littoral Combat Ship - Freedom/Independence

Looks like, the Navy wants that the LCS is changed from a corvette to a frigate.

Links:

http://intercepts.defensenews.com/2014/12/a-closer-look-at-the-modified-lcs/

http://www.defensenews.com/article/20141211/DEFREG02/312110041/Split-Decision-New-US-Navy-Ship

Attachments

I was really hoping that the task force was going to recommend a new frigate.

I'm guessing Torpedo defense includes CAT? (Countermeasure Anti-Torpedo) http://news.usni.org/2013/06/20/navy-develops-torpedo-killing-torpedo

marauder2048

"I should really just relax"

- Joined

- 19 November 2013

- Messages

- 3,157

- Reaction score

- 926

sferrin said:It could be really, really good but if you only have 8 of them on hand (if that) that's a problem. I'd like to know why they couldn't put an 8-cell, SD length Mk41 with 32 ESSMs on board. Seems like that would be a no-brainer.TomS said:I don't think anyone seriously should have expected a new hull design out of SSC. I'm a bit surprised they still aren't fitting VLS of any sort, though. That is going to keep LCS from carrying antiaircraft missiles other than RAM. I hope RAM Block 2 is really, really good.

Can't the RAM launcher be reloaded at sea? I don't know what timeframe they are looking at for these upgrades but ESSM Block 2 wouldn't require the illuminators and would have some OTH Anti-surface capability.

- Joined

- 3 June 2011

- Messages

- 18,379

- Reaction score

- 12,335

marauder2048 said:Can't the RAM launcher be reloaded at sea?

Sure, by hand.

[/quote]

marauder2048

"I should really just relax"

- Joined

- 19 November 2013

- Messages

- 3,157

- Reaction score

- 926

sferrin said:marauder2048 said:Can't the RAM launcher be reloaded at sea?

Sure, by hand.

Are you suggesting that that capability isn't useful?

- Joined

- 3 June 2011

- Messages

- 18,379

- Reaction score

- 12,335

marauder2048 said:sferrin said:marauder2048 said:Can't the RAM launcher be reloaded at sea?

Sure, by hand.

Are you suggesting that that capability isn't useful?

Is that a serious question?[/quote]

marauder2048

"I should really just relax"

- Joined

- 19 November 2013

- Messages

- 3,157

- Reaction score

- 926

sferrin said:marauder2048 said:sferrin said:marauder2048 said:Can't the RAM launcher be reloaded at sea?

Sure, by hand.

Are you suggesting that that capability isn't useful?

Is that a serious question?

Jeez, <b>Snarky</b>ferrin 'twas just a wee query.

The major point is that the RAM launcher can fire a variety of weapons and can be reloaded at sea. The VLS can do the former but can't do the latter.

- Joined

- 3 June 2011

- Messages

- 18,379

- Reaction score

- 12,335

The RAM launcher can fire the RAM missile. The SeaRAM launcher only carries 11 missiles (less if they decide to upgrade to the Block II). That it can be reloaded is pretty much a moot point given how time consuming it is. As for the launcher being able to fire other missiles I've not seen any evidence of it either being tested or deployed that way. Furthermore, if you put other types in the launcher it only reduces the already low number of RAM missiles available for defense.

marauder2048

"I should really just relax"

- Joined

- 19 November 2013

- Messages

- 3,157

- Reaction score

- 926

sferrin said:The RAM launcher can fire the RAM missile. The SeaRAM launcher only carries 11 missiles (less if they decide to upgrade to the Block II). That it can be reloaded is pretty much a moot point given how time consuming it is. As for the launcher being able to fire other missiles I've not seen any evidence of it either being tested or deployed that way. Furthermore, if you put other types in the launcher it only reduces the already low number of RAM missiles available for defense.

http://investor.raytheon.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=84193&p=irol-newsArticle&ID=1684336

It's fired Griffin. And the time taken to reload is dramatically less than the time required to disengage, steam back to port, reload the VLS and then steam back.

- Joined

- 3 June 2011

- Messages

- 18,379

- Reaction score

- 12,335

marauder2048 said:sferrin said:The RAM launcher can fire the RAM missile. The SeaRAM launcher only carries 11 missiles (less if they decide to upgrade to the Block II). That it can be reloaded is pretty much a moot point given how time consuming it is. As for the launcher being able to fire other missiles I've not seen any evidence of it either being tested or deployed that way. Furthermore, if you put other types in the launcher it only reduces the already low number of RAM missiles available for defense.

http://investor.raytheon.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=84193&p=irol-newsArticle&ID=1684336

It's fired Griffin. And the time taken to reload is dramatically less than the time required to disengage, steam back to port, reload the VLS and then steam back.

Which will be a great comfort to those guys valiantly trying to reload that launcher while the antiship missiles are coming in. BTW Griffin weighs about 1/6th the weight of RAM so it's reload time is irrelevant.

marauder2048

"I should really just relax"

- Joined

- 19 November 2013

- Messages

- 3,157

- Reaction score

- 926

sferrin said:BTW Griffin weighs about 1/6th the weight of RAM so it's reload time is irrelevant.

Sure, that version of Griffin. There are others. The main point is that RAM can fire other missiles contrary to your claim.

sferrin said:Which will be a great comfort to those guys valiantly trying to reload that launcher while the antiship missiles are coming in

As opposed to valiantly not being able to reload the VLS? Yeah...trying to break contact to steam back to port in order to reload while under fire sounds far more comforting.

I'm not saying that LCS doesn't need a VLS but it's highly desirable to have complementary capabilities.

donnage99

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 16 June 2008

- Messages

- 1,362

- Reaction score

- 892

This ship doesn't just need weapons, it needs range to exploit its excellent speed's usefulness. There's no point in having the speed when you have to go as slow as the oiler that would accompany you to refuel you half way across the atlantic. But of course, that means building a larger ship that is actually a frigate. This is the painful truth of having to modify a ship that was built around a drastically different vision. I say, dump the freedom class, which is a little cheaper but a tons less capable, and invest that money into modifying the more capable independence class that not only will have decent weapons but range required to be tactically relevant.

- Joined

- 3 June 2011

- Messages

- 18,379

- Reaction score

- 12,335

marauder2048 said:sferrin said:BTW Griffin weighs about 1/6th the weight of RAM so it's reload time is irrelevant.

Sure, that version of Griffin. There are others. The main point is that RAM can fire other missiles contrary to your claim.

Go back and read what I said. And which "others"?

marauder2048 said:sferrin said:Which will be a great comfort to those guys valiantly trying to reload that launcher while the antiship missiles are coming in

As opposed to valiantly not being able to reload the VLS? Yeah...trying to break contact to steam back to port in order to reload while under fire sounds far more comforting.

I guarantee you, having 32 missiles sitting in a VLS would be far more comforting than having 11 (or far less if you had your way) missiles available and being expected to run out on deck to reload while being shot at. LOL

- Joined

- 4 July 2010

- Messages

- 2,516

- Reaction score

- 3,107

Sferrin, I can understand your desire for bigger teeth, but you're skipping a lot of practical considerations. 32 ESSMs in an 8-cell SD VLS is going to run up around 25 metric tons, before radar and combat system upgrades. SeaRAM with 11 missiles is less than 7 metric tons and needs no further additions to the LCS. In a pair of hulls which already have weight problems, another 18+ tons is a dramatic increase. Add in the volume requirements, and either something has to come off or the hulls must be more extensively modified at additional cost.

And on the subject of cost, where has the Hill indicated they would be willing to pay for a significant increase in LCS/SSC cost? This fairly mild upgrade is projected to add about $50 million to each hull, on a ship which Congress already complains is too expensive, within a shipbuilding budget which is already under-funded. Change that $50 million increase to $150 or $200 million and the "more capable" SSC will get cancelled long before it sees the light of day.

And on the subject of cost, where has the Hill indicated they would be willing to pay for a significant increase in LCS/SSC cost? This fairly mild upgrade is projected to add about $50 million to each hull, on a ship which Congress already complains is too expensive, within a shipbuilding budget which is already under-funded. Change that $50 million increase to $150 or $200 million and the "more capable" SSC will get cancelled long before it sees the light of day.

DrRansom

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 15 December 2012

- Messages

- 701

- Reaction score

- 303

To add to Moose's point, it was reported (Breaking Defense, I believe) that the upgrades will actually reduce the ship's weight. That goal would be extremely difficult with an 8 cell VLS. The advantage of cruise missiles is the minimal connection needed to the ship's central systems and no need to upgrade anything other than fire control box and a box launcher.

What I am interested in seeing is the signature reduction, or at least the Navy's plans for that. There was a report about signature reduction on a DDG-51, this would continue that a trend towards that.

Now, I think that the lack of a VLS does lead to a serious problem: no ASROC. If the LCS detects a submarine contact, it must use some helicopter to persecute the target. In bad weather, that may not be possible. If there was a VLS, I think it'd likely be: 4 x ASROC, 16 ESSM.

What I am interested in seeing is the signature reduction, or at least the Navy's plans for that. There was a report about signature reduction on a DDG-51, this would continue that a trend towards that.

Now, I think that the lack of a VLS does lead to a serious problem: no ASROC. If the LCS detects a submarine contact, it must use some helicopter to persecute the target. In bad weather, that may not be possible. If there was a VLS, I think it'd likely be: 4 x ASROC, 16 ESSM.

I'm sorry if this is (slightly) off topic, but since SCS and FCR have been mentioned, does anybody know what happened to the SPY-5 radar offered by Raytheon back in 2009-2010 ?TomS said:sferrin said:It could be really, really good but if you only have 8 of them on hand (if that) that's a problem. I'd like to know why they couldn't put an 8-cell, SD length Mk41 with 32 ESSMs on board. Seems like that would be a no-brainer.

The issue probably isn't the VLS istelf but fire control and the associated combat direction system. Adding 3-D radar is a start, but adding illuminators and the necessary processing and control consoles in the CIC would mean a bunch more complexity (cost) and manning (also cost). I'm sure that's what drove the omission. It just strikes me as incredibly "penny wise, pound foolish."

We've not heard anything about this radar since then and it's now disappeared from Raytheon's website.

Technical failure or just another product that didn't find its market ?

I thought ASROC was out of service?

- Joined

- 3 June 2011

- Messages

- 18,379

- Reaction score

- 12,335

covert_shores said:I thought ASROC was out of service?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fk4p3fVFMZg

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RUM-139_VL-ASROC

- Joined

- 4 July 2010

- Messages

- 2,516

- Reaction score

- 3,107

I think it was just a concept to build off their SPY-3 work on the low end. Since then they appear to have realigned their naval radar work to focus on AMDR and derivatives of it for the time being.Matt R. said:Technical failure or just another product that didn't find its market ?

marauder2048

"I should really just relax"

- Joined

- 19 November 2013

- Messages

- 3,157

- Reaction score

- 926

Moose said:I think it was just a concept to build off their SPY-3 work on the low end. Since then they appear to have realigned their naval radar work to focus on AMDR and derivatives of it for the time being.Matt R. said:Technical failure or just another product that didn't find its market ?

I wonder if it fell down on ITAR concerns since I believe it was intended as a retrofit to the exported Perry class frigates..

Moose said:I think it was just a concept to build off their SPY-3 work on the low end. Since then they appear to have realigned their naval radar work to focus on AMDR and derivatives of it for the time being.Matt R. said:Technical failure or just another product that didn't find its market ?

Hi Moose,

AIUI, SPY-5 didn't share the same technology as SPY-3 (PESA for the former vs GaAs AESA for the latter), was more than a mere concept (a dual-face EDM model was installed at Raytheon's test site, with full system qualification expected by the end of 2010) and wasn't targeted at the same market as AMDR / SPY-3 (SPY-5 was meant for SSCs, large gators & CVs).

marauder2048 said:Moose said:I think it was just a concept to build off their SPY-3 work on the low end. Since then they appear to have realigned their naval radar work to focus on AMDR and derivatives of it for the time being.Matt R. said:Technical failure or just another product that didn't find its market ?

I wonder if it fell down on ITAR concerns since I believe it was intended as a retrofit to the exported Perry class frigates..

Hi Maurader,

It is my understanding that SPY-5 was not only intended as a retrofit for the Perry class frigates, but also as a possible replacement for the Mark-95 CWI used on US gators & CVNs, with which it shared common components like the Mark-73 Mod.3 Solid-State Transmitter (SSTX) and the Mark-30 Mod.0 Integrated Radar Processor (IRP).

- Joined

- 4 July 2010

- Messages

- 2,516

- Reaction score

- 3,107

You probably know more, I wasn't aware SPY-5 was being sold as a GaN radar.Matt R. said:Moose said:I think it was just a concept to build off their SPY-3 work on the low end. Since then they appear to have realigned their naval radar work to focus on AMDR and derivatives of it for the time being.Matt R. said:Technical failure or just another product that didn't find its market ?

Hi Moose,

AIUI, SPY-5 didn't share the same technology as SPY-3 (PESA for the former vs GaN AESA for the latter), was more than a mere concept (a dual-face EDM model was installed at Raytheon's test site, with full system qualification expected by the end of 2010) and wasn't targeted at the same market as AMDR / SPY-3 (SPY-5 was meant for SSCs, large gators & CVs).

My bad.Moose said:You probably know more, I wasn't aware SPY-5 was being sold as a GaN radar.Matt R. said:Moose said:I think it was just a concept to build off their SPY-3 work on the low end. Since then they appear to have realigned their naval radar work to focus on AMDR and derivatives of it for the time being.Matt R. said:Technical failure or just another product that didn't find its market ?

Hi Moose,

AIUI, SPY-5 didn't share the same technology as SPY-3 (PESA for the former vs GaN AESA for the latter), was more than a mere concept (a dual-face EDM model was installed at Raytheon's test site, with full system qualification expected by the end of 2010) and wasn't targeted at the same market as AMDR / SPY-3 (SPY-5 was meant for SSCs, large gators & CVs).

SPY-3 is GaAs AESA.

SPY-5 is PESA.

"NavWeek: Frigate About It"

Feb 13, 2015 by Michael Fabey in Ares

Source:

http://aviationweek.com/blog/navweek-frigate-about-it

Feb 13, 2015 by Michael Fabey in Ares

Source:

http://aviationweek.com/blog/navweek-frigate-about-it

The die is cast and the U.S. Navy has made its big bet – the Littoral Combat Ship (LCS)-Next is going to be an uparmed and uparmored version of the current vessels that the service has redesignated as an FF, or fast frigate.

"These are not ‘L' class ships," Navy Secretary Ray Mabus said last month during his keynote address at the Surface Navy Association (SNA) National Symposium. "When I hear ‘L,’ I think amphib. I spend a good bit of my time explaining what ‘littoral’ is." It is a good time, he says, to re-establish Navy tradition for naming ships properly. "It’s a frigate. We’re going to call it one."

Of course calling it one won’t make it one. Many doubt the idea that that the modified LCS will live up to the true definition of a frigate. But perhaps it's about time to give the Navy a chance to prove out its case. The service brass says it has the ships it wants and everyone can argue over the next few years whether the decision is a good one, but the truth is that only time will tell whether the gamble will be worth it. Indeed, with the new Navy focus on “distributive lethality,” where every ship will be armed up as much as possible, it’s difficult and perhaps impossible now to foresee how the new FFs will fare in the future force structure.

Having said that, it’s also time to clear up a few things about LCS performance thus far that factored into the Navy’s LCS-FF decision.

The Pentagon's Director of Operational Test and Evaluation (DOT&E) says in its recently released annual report: “While offering some improvements in combat capability and survivability (primarily via reduced susceptibility) relative to LCS, the minor modifications to LCS considered by the Task Force and recommended by the Navy Leadership do not satisfy significant elements of a capability concept developed by the Task Force for a modern frigate.”

Navy officials say DOT&E's evaluation was factored into the task force decision process. Such statements imply DOT&E supports the plan – it obviously does not. Navy officials, though, have always questioned LCS detractors, even official government ones, throughout the years. In a common refrain, Mabus told symposium attendees, “I’ve read the stories, like you have, about the problems in the LCS program, but they are all written with data that is a couple of years old. Those claims are based on bad data. Now that we are in serial construction on both classes of these ships the costs keep coming down and they are launching on schedule. When we inherited this program it did have a lot of problems. But in the past five years we have turned it around and these classes have become an acquisition success story and they are now coming in well under the Congressional cost cap.”

In many cases the stories Mabus refers to were based on the reports by the DOT&E, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and other government sources.

There is no doubt that they are well-researched and well-intentioned. But Mabus still has a point, because it is impossible to do these kinds of reports in real time. The studies are snapshots of data and performance at a certain period of time that are analyzed, synthesized and verbalized. Still, these are smart folks doing these reports, and they are still providing valuable and pertinent insight.

Some points of those troubling reports are still valid. “Key unknowns remain regarding how the Navy will eventually be able to use the LCS and how well the ship meets its performance requirements,” GAO says in a report about LCS released this past summer.

GAO based its report on data, interviews and observations about the performance of LCS 1 USS Freedom – the steel monohull variant of the vessel build by Lockheed Martin – in the West Pacific for the 7th Fleet.

“While 7th Fleet officials noted that a benefit of having LCS in theater was that the ship could participate in international exercises, freeing up other surface combatants for other missions, they were still not certain about the ship’s potential capabilities and attributes, or how they would best utilize an LCS in their theater,” GAO says.

It should be noted that LCS 3 Fort Worth is now in the same theater, performing all types of missions and operations, planned and opportunistic, for the 7th Fleet and apparently doing them well. The ship is an improved Freedom-class vessel and the reviews have been much more positive.

However, GAO makes some points that are worth considering. “Fleet users expressed interest in several modifications that they would like to see made to the seaframes and/or mission packages to better suit their needs, based on their experience with the deployment.”

They want a replacement system for an unreliable and poorly performing electronic warfare system called WBR-2000 currently installed on the Freedom variant.

They also want use the MH-60 helicopter to carry sonar buoys on the ship for helicopter use even if the anti-submarine warfare package is not onboard.

They want an intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR)-specific mission package.

According to the 7th Fleet users, GAO notes, “These changes would make LCS more reflective of their theater-specific needs.”

It appears that the FF modifications, planned to be backfitted on LCS vessels, should address some of these concerns. But GAO also worries as much about how the ships are operated as how they are equipped.

The Navy failed to demonstrate certain LCS concepts on the deployment and cannot extrapolate some of the lessons learned across the whole LCS class, GAO says.

In another report on the Freedom deployment, GAO says, “For over 10 years, the Navy has been refining the concept of operations for its newest class of surface warship.”

Part of the problem may be getting the ships out to sea enough to get the necessary data and feel for the ship. There simply has not been enough water under the keel.

“Since the ships have been delivered, USS Freedom has spent 29% of its time under way, while [LCS 2, the Austal USA-built] USS Independence has spent 26% of its time under way,” GAO says.

A ship’s operational concepts define the character of the ship. “Questions remaining regarding LCS’s underlying concepts will, in turn, have implications for the practicality of certain requirements and key differences between the two variants—issues that have the potential to affect future acquisition decisions,” GAO says.

One of the core concepts for LCS has been its low manning – with “low” taking on a relative meaning as time goes by. The core crew of 40 is now already up to 50, and GAO says that still may not be enough.

“Based on our conversations with the crew on the second half of the deployment, they were strained to keep up with some duties even with the additional people,” GAO says.

Sleep is an issue. The officials Navy standard is eight hours of sleep per day – though many ship crews, at some time or another don’t meet that number. The average on LCS is below that, crews told GAO.

The Center for Naval Analyses found that Freedom crews averaged six hours of sleep per day, GAO says, adding, “Some key departments, such as engineering and operations, averaged even fewer.”

Navy officials told GAO sailors do not realistically expect 8 hours of sleep while they are under way and may choose to have more down time rather than sleep.

One of the biggest human-power drains on any ship is maintenance, and LCS is no different. But it’s a bigger headache because of the smaller crew base. “The crew also reported heavy reliance on the mission package crew to conduct seaframe maintenance—which is not their role,” GAO says.

When the mission package crew had to perform its own missions, the LCS sailors had to work even harder to maintain the ship, causing them to become even more fatigued.

Some of the problems have to do with the way maintenance has to be done on the ships. “Members of the combat systems department crew reported that approximately 90% of combat systems spaces are sensitive and therefore require the presence of LCS crew members in the workspace while contractors complete maintenance on department systems,” GAO reports. “Crew members must essentially ‘shadow’ contractors as they perform such basic tasks as changing batteries and cleaning filters.”

The number of shore personnel to support the ship has more than tripled—from 271 to 862—as support requirements have become better understood, according to GAO.

The ship hulls still pose significant acquisition risks for the program, GAO says. “Key among these is managing the weight of the ships. Initial LCS seaframes face limitations resulting from weight growth during construction of the first several ships. This weight growth has required the Navy to make compromises on performance of LCS 1 and LCS 2 and may complicate existing plans to make additional changes to each seaframe design.”

All ships grow heavier over time and the Navy accounts for this with an expected weight allowance. But, GAO says, LCS has significantly lower available margin compared to other ship classes.

One of the reasons for the weight concern has been the over-arching requirement for extremely high warship speed – as close to 50 kt. as possible. Navy officials now say they are willing to sacrifice some of that speed on the FFs and backfitted LCS vessels, although how much is an open question, especially with engineers still searching for ways to shave tonnage as some of the mission module package equipment meant to be switched out will now become permanently anchored aboard.

How will all of this affect cost? Well, it was hard enough before just to pin down overall LCS costs.

“The Navy estimated in 2011 that operations and support costs for the LCS seaframes would be about $50 billion over the life of the ship class,” GAO says. “In 2013, it estimated that operations and support costs for the mission modules would be about $18 billion. Both of these estimates were calculated in fiscal year 2010 dollars. However … the seaframe estimate is at the 10% confidence level, meaning that there is 90% chance that costs will be higher than this estimate.”

The Navy didn’t have actual LCS data yet to make its estimates, GAO notes, so the service used operations and support data from other surface ships, such as frigates, and modified them to approximate LCS characteristics.

“The maintenance concepts for these ships differ from those for the LCS,” GAO points out.

From the outset of the program, the Navy has described the LCS as a low-cost alternative to other ships in the surface fleet, GAO notes. “Yet the available data indicate that the per-year, per ship life-cycle costs are nearing or may exceed those of other surface ships, including multimission ships with greater size and larger crews.”

LCS per-year-cost estimates “are nearing or may exceed the costs of other surface ships … such as guided-missile frigates and destroyers,” GAO says.

The Pentagon told GAO it is “concerned with the conclusions drawn from the analysis of life-cycle cost data across ship classes,” saying “due to known gaps in existing ship class cost data, the available data do not allow for an accurate comparison of the life cycle costs among LCS and other existing surface ship classes.”

In interviews with Ares, Navy officials say some research and development (R&D) for other ships was done in-house by the Navy and would not show up in the total cost figures as they do for LCS, where it was done by the contractors.

“In its comments, DOD noted differences in the scope of cost data across the ship classes and differences in life-cycle phases among the ship classes included in our life-cycle cost analysis,” GAO says.

The Pentagon told GAO, “There are gaps in the Navy’s record keeping for operations and support costs, so that some potential costs may not be captured in the estimates the Navy provided, such as system modernization, software maintenance, and program startup, which could understate the costs of the other surface ships.”

GAO says it used the “the most comprehensive operations and support cost data” the Navy could provide.

“The Navy also has used these data from other surface ship classes to build its LCS life-cycle cost estimates,” GAO says.

Navy officials can raise questions about the timeliness of the data used in GAO reports. And the service brass can also question the operational savvy of government auditors when reviewing ship programs. But the GAO issued warnings about potential programmatic upheavals after the Navy started in on the LCS block buys should it be determined that the service had to make any mid-stream changes – and those accountants have started to look prophetic.

Still, the Navy deserves a chance to see how its current plan plays out, especially given the performance during recent LCS operations.

After the Freedom’s rocky first Western Pacific deployment, the LCS program made a comeback first with the Independence in the Rim of Pacific (Rimpac) exercise last summer off the coast of Hawaii, and then with the current string of Fort Worth successes in the Pacific.

The Independence arrived in Rimpac with about a third of a tank of gas to spare, without incident. The ship performed a variety of usual surface warship missions as well as some special ones, including acting as launching vessel for about four dozen Seals, Marines and other special operators from an assortment of different countries using rigid-hull boats and an MH-60R helicopter to conduct a security operation.

The operators used the surface warfare package equipment already on board the ship as well as their own communication gear, says Cmdr. Joseph Gagliano, Independence commanding officer for Rimpac operations. During the exercises, he says, the ship was able to launch aircraft at a rapid pace, thanks to its aviation-friendly design. The ship’s crew, he says, have been able to find ways of using the ship’s speed, stealth and other assets to provide tactical advantages.

Such a ship, armed with the right kind of missiles or other weaponry in years to come, could give the enemy pause – at least that’s the Navy's thinking now. They could send out LCS vessels or FFs with destroyers and cruisers and make adversaries wonder where the next attack could come from.

Add into the mix small armed boats or unmanned surface vessels – like Juliet Marine Systems’ prototype small-attack craft based on the Swath concept that looks something like a sea-skimming F-117, called Ghost – and then it could really get interesting.

High-stakes betting usually is.

One can upgrade all the weapons on the platform they want. The compartmentalization and water tight integrity is not affected. THAT is what survivability is all about.

All this talk about "L" class vessels and less expensive surface combatants is a practical demonstration of "Living on a River in Egypt."

Still trying to figure out how one can Escort a convoy with an AAW weapon with a 25lb blast fragmentation warhead on a missile with a max range of under 6 miles. HHUMMMM

Despite the name change (the Navy did something similar in 1975 reclassifying Destroyer Escorts (DE) as Frigates (FF)) and the added weapons and other improvements, the Freedom/Independence class are still woefully under armed for a frigate.

These ships still lack an organic medium range SAM, an ASW weapon and torpedoes that are found on similar size ships. Adding a 16-cell VLS module would provide the capability to carry 32 ESSM and 8 VLS ASROC. But, adding ESSM would require additional electronics that probably cannot not be mounted on the ship in its current configuration. Until a ASM is identified, I can't understand why the Navy cannot equip these ships with Harpoon missiles as an interim solution.

Bgray said:So, it's a bit late, but I read that about 18 companies proposed ships for this-- any information on their concepts?

I haven't seen anything beyond what we have already documented.

- Joined

- 4 July 2010

- Messages

- 2,516

- Reaction score

- 3,107

Most of the US shipyards haven't embraced online media all that well, so you usually only see the "for public consumption" version of their concepts in the form of models/posters at trade shows. Otherwise, we're unlikely to see much of their submissions unless the Navy puts some of them out there for us to see.

- Joined

- 9 October 2009

- Messages

- 22,041

- Reaction score

- 13,748

scifibug said:For everyone who thought the LCS were an interesting but unworkable, underarmed, undermanned concept, the USN has FINALLY figured it out.

http://www.defense-aerospace.com/articles-view/release/3/176873/us-navy-drops-lcs-plans,-concept-after-latest-failures.html

Now we have to wait and see if the Navy's fix of single use ships based on the two LCS models now being built or it will follow the GAO and start over maybe being based on a foreign design.

marauder2048

"I should really just relax"

- Joined

- 19 November 2013

- Messages

- 3,157

- Reaction score

- 926

Grey Havoc said:

de Briganti really seems to be impervious to knowledge or understanding of procurement particularly unit costs for ships which in government reports and budgetary documents excludes "government furnished equipment" which can, in the case of DDG-51, nearly double the unit cost. It's not even remotely close for LCS.