Problem was, nobody wanted to suceed Webb, so close from JFK deadline - early 1969. Nixon asked Simon "TRW" Ramo and Bernard "ICBM" Schriever, but both declined the job. Paine assumed he would be sacked because of the LBJ - Nixon transition, but Nixon per lack of a better choice, kept him.

I wonder what a Schriever NASA would look like, and what would happen to the MOL (since it was some months before cancellation).

But I think that's essentially irrelevant. The NASA administrator implements policy, but has only a limited role in making the policy. The problem was that the Nixon administration didn't care all that much about space. Nixon himself liked astronauts, but was indifferent to spaceflight. Many of the people around him didn't care about it and were also interested in cutting budgets back, and space was still a fat budget to cut. So they went after NASA rather severely to cut the budgets.

There's a great memo from around 1971 or so where Caspar Weinberger (who would become Secretary of Defense under Reagan) wrote to Nixon saying that they needed to continue human spaceflight and not eliminate it entirely, and he laid out several reasons. It was clear that Nixon's budget cutters wanted to eliminate it. Nixon wrote "I agree with Cap" on the side of the memo and that settled the issue. But the knives were out.

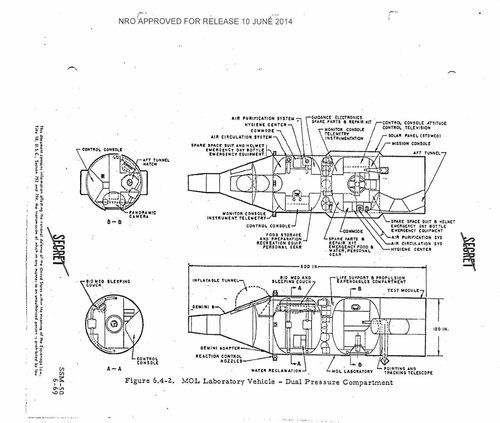

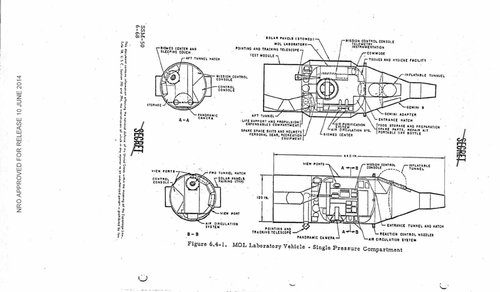

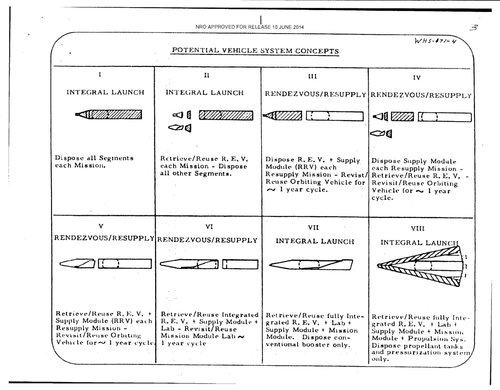

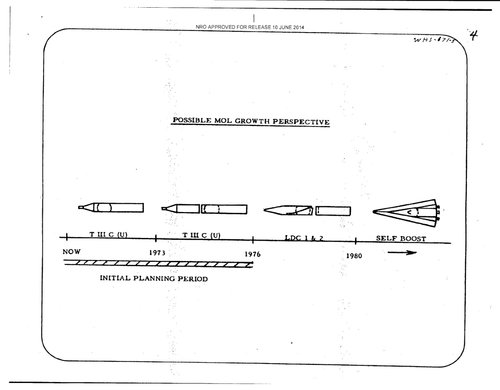

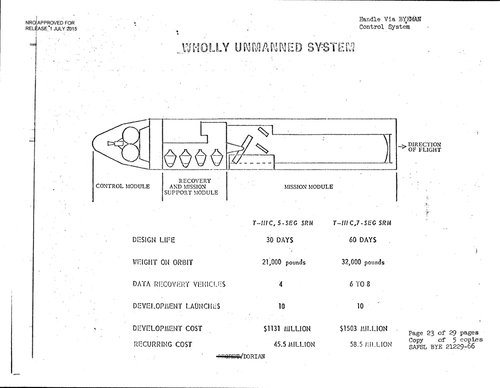

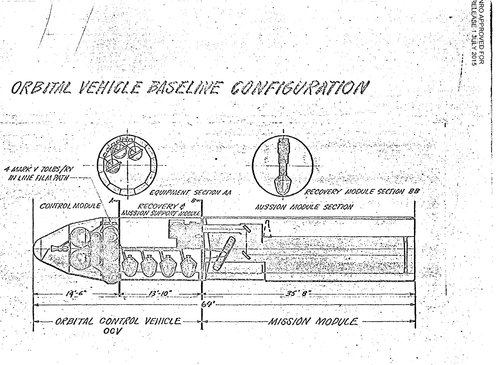

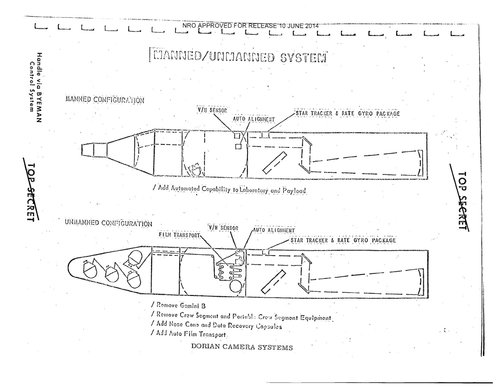

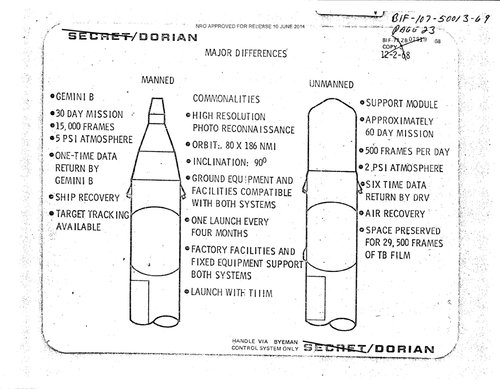

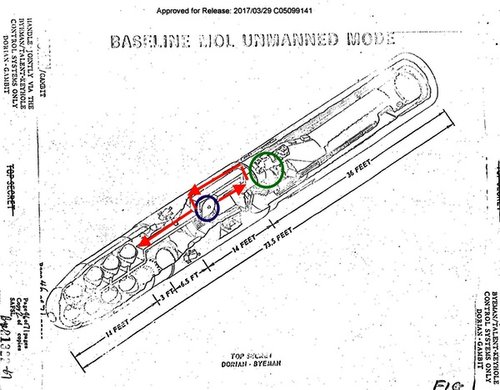

As for MOL, the big problem with MOL was that it was always a niche capability, and that niche kept getting smaller and smaller as the robotic reconnaissance satellites got better. One of the initial justifications for having astronauts on MOL was that they would focus and fine tune the optics. But within a year or so it was clear that automatic systems could do that and you did not need an astronaut for that. Then the argument was that the astronauts would prioritize the photography, going after the most important targets as they flew overhead. Although that was a legitimate role for an astronaut considering that a very-high-resolution camera could only photograph a few targets during each pass overhead, it was a rather unconvincing argument for many. Are those few photographs that they take really going to be so important that it justifies the expense of putting astronauts up there? MOL included an unmanned version from around 1966 or so, and that really undercut the argument--if it could fly

unmanned, why did it need to fly

manned?

But you also need to consider what MOL was competing with for money: the KH-9 HEXAGON was going to cover massive amounts of territory at pretty good resolution (note: the "2-3 feet" resolution in the unclassified documents is misleading: the best missions were

way better than that). MOL was going to fly over the Soviet Union and stick little pins in the map in terms of coverage. By contrast, HEXAGON would fly over and cover

everything in only a few days. HEXAGON could photograph--in a single image--two Soviet bomber bases a few hundred miles apart. It was massively powerful. That translated into a strong argument to make to the president: a HEXAGON mission could count every aircraft on every airfield in the Soviet Union in a few days; it could count every missile silo and every ship in port and almost every tank and armored vehicle. As a tool for assessing what the Soviet Union had in terms of weapons, and what it was about to do in terms of intentions (like invading a neighbor), it was unmatched. So when MOL and HEXAGON went head to head for funding in an administration that wanted to cut budgets, MOL was the weaker mission and it lost out.