You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Martin P6M Seamaster

- Joined

- 9 October 2009

- Messages

- 21,841

- Reaction score

- 13,373

Some relevant posts from the 'BAE SYSTEMS Nimrod MRA.4' thread:

I think Seamaster was a nuclear highspeed bomber, not ASW. Admittedly the difference now is minimal, although I'd expect the 'backseaters' to have a view, as at least the seamaster gave everyone a bang seat.Not quite. The USN's Martin P6M Seamaster for example was killed off by the perceived need to pour money into covering rather large Polaris program cost overruns.As it turned out only the RAF wanted such a fast ASW aircraft, everyone else went for props (Atlantique, Orion, Il38).

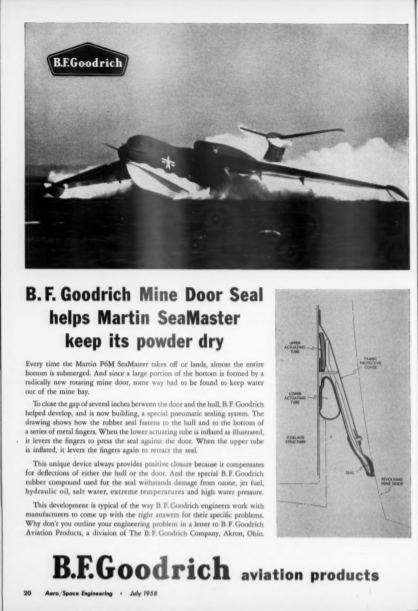

Seamaster was nominally an offensive minelayer. The USN rationalized that as a "sea control" role, the idea being to mine Soviet naval bases and bottle up their subs and surface ships in the early stages of a conflict. But it was clearly designed around delivery of large nuclear weapons. The "minelaying" mission was pretty much a fig leaf to get around the directives limiting the USN to sea control, rather than strategic nuclear strike. It was never an ASW patrol aircraft.

While they did use the minelaying role to help obfuscate the Seamaster's nuclear strike role, the United States Navy treated the aircraft's mine warfare capabilities quite seriously as well. Memories were still fresh of the mauling the navy had received in the Korean War from sea mines, so being able to freely & rapidly deploy both conventional and atomic sea mines across whole theaters was rightly considered vital to help counter sortieing Eastern Block naval forces (including their own mine warfare forces!).

Fair point. They were also very aware of the analysis in the US Strategic Bombing Survey, which showed how effective mine warfare had been in crippling Japanese coastwise shipping.

They could have put some N-156N on the deck for escort...

- Joined

- 9 October 2009

- Messages

- 21,841

- Reaction score

- 13,373

I don't think there would have been enough deck space left with the conversion to operate them. Does make me wonder though if they considered a optional small detachment of VTOL fighters for more vulnerable operating areas. Imagine something like a couple of P.1154 supersonic VTOLs operating from her!

EDIT: Via Hushkit;

EDIT: Via Hushkit;

Last edited:

Firefinder

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 5 October 2019

- Messages

- 1,035

- Reaction score

- 1,861

According to this apperantly Bruships also looked into a Submarine Tender for the Seaplane Striking force.

I found it here.

theleansubmariner.com

theleansubmariner.com

Anyone got anymore information on it?

I found it here.

Obstacles to Overcome – Building the Polaris Submarine

Obstacles to Overcome – Building the Polaris Submarine It is a well-known fact among the submarine community that the USS George Washington started out life as the fast attack submarine Scorpion. B…

theleansubmariner.com

theleansubmariner.com

Anyone got anymore information on it?

Attachments

Last edited:

taildragger

You can count on me - I won a contest

- Joined

- 2 November 2008

- Messages

- 403

- Reaction score

- 497

"atomic sea mines"??Memories were still fresh of the mauling the navy had received in the Korean War from sea mines, so being able to freely & rapidly deploy both conventional and atomic sea mines across whole theaters was rightly considered vital to help counter sortieing Eastern Block naval forces (including their own mine warfare forces!).

That seems like a bad idea for a whole bunch of reasons. Do you have evidence that they exist/existed in reality or as a serious proposal? I can almost see a rationale for the Soviets to think about such a weapon to deliver a knockout blow to a USN carrier, but what use would the US have for them?

Firefinder

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 5 October 2019

- Messages

- 1,035

- Reaction score

- 1,861

The Baker shot of Operation Crossroads was a test of one such mine. With the idea behind them being that you only need a handful to lovk down an area, say a Strait."atomic sea mines"??Memories were still fresh of the mauling the navy had received in the Korean War from sea mines, so being able to freely & rapidly deploy both conventional and atomic sea mines across whole theaters was rightly considered vital to help counter sortieing Eastern Block naval forces (including their own mine warfare forces!).

That seems like a bad idea for a whole bunch of reasons. Do you have evidence that they exist/existed in reality or as a serious proposal? I can almost see a rationale for the Soviets to think about such a weapon to deliver a knockout blow to a USN carrier, but what use would the US have for them?

With them being effective on both surface and subsurface threats.

The subsurface part was a biggy since beforehand you need hundards per kilometer to keep a sub out. But with nukes you only need one per 500 to few thousand meters depending on yield. Have the nuke in the center of a web of sensors? A sub will a bad time...

You also only needed to consider blocking a relatively small number of major fleet bases and connecting seaways if your enemy was expected to be the USSR.The Baker shot of Operation Crossroads was a test of one such mine. With the idea behind them being that you only need a handful to lovk down an area, say a Strait."atomic sea mines"??Memories were still fresh of the mauling the navy had received in the Korean War from sea mines, so being able to freely & rapidly deploy both conventional and atomic sea mines across whole theaters was rightly considered vital to help counter sortieing Eastern Block naval forces (including their own mine warfare forces!).

That seems like a bad idea for a whole bunch of reasons. Do you have evidence that they exist/existed in reality or as a serious proposal? I can almost see a rationale for the Soviets to think about such a weapon to deliver a knockout blow to a USN carrier, but what use would the US have for them?

With them being effective on both surface and subsurface threats.

The subsurface part was a biggy since beforehand you need hundards per kilometer to keep a sub out. But with nukes you only need one per 500 to few thousand meters depending on yield. Have the nuke in the center of a web of sensors? A sub will a bad time...

Nuclear sea mines were undoubtedly a bad idea when you consider the ramifications. But, in the post-WW2 period, few did. Here in the US, we scared ourselves silly thinking about Red Menaces of one sort or another, and fear tends to make people ignore consequences in the rush to find security. A lot of terrible ideas were seriously considered and, in many cases, actually fielded.

- Joined

- 5 May 2007

- Messages

- 1,442

- Reaction score

- 2,746

The threat of nuclear mines was also one of the initial drivers for the development of minehunters in place of minesweepers. Clearing nuclear mines by sweeping means you very quickly run out of minesweepers. And possibly ports.You also only needed to consider blocking a relatively small number of major fleet bases and connecting seaways if your enemy was expected to be the USSR.

taildragger

You can count on me - I won a contest

- Joined

- 2 November 2008

- Messages

- 403

- Reaction score

- 497

So instead of a bunch of moderately costly but expendable mines, you use a bunch of less expensive sensors and one fabulously expensive atomic weapon that you can't afford to have fall into enemy hands. I can't think of anyway to link the sensors to the mine other than acoustically or via cable. The former would make it easy to detonate the mine (easy unless it's just offshore a city you're fond of) once the first sensor is examined. The latter would make it easy to locate the mine once the first sensor is found.The Baker shot of Operation Crossroads was a test of one such mine. With the idea behind them being that you only need a handful to lovk down an area, say a Strait."atomic sea mines"??Memories were still fresh of the mauling the navy had received in the Korean War from sea mines, so being able to freely & rapidly deploy both conventional and atomic sea mines across whole theaters was rightly considered vital to help counter sortieing Eastern Block naval forces (including their own mine warfare forces!).

That seems like a bad idea for a whole bunch of reasons. Do you have evidence that they exist/existed in reality or as a serious proposal? I can almost see a rationale for the Soviets to think about such a weapon to deliver a knockout blow to a USN carrier, but what use would the US have for them?

With them being effective on both surface and subsurface threats.

The subsurface part was a biggy since beforehand you need hundards per kilometer to keep a sub out. But with nukes you only need one per 500 to few thousand meters depending on yield. Have the nuke in the center of a web of sensors? A sub will a bad time...

- Joined

- 9 October 2009

- Messages

- 21,841

- Reaction score

- 13,373

Not necessarily. There are a fair number of ways to rig a sensor network's topology to make an opponents life quite miserable for example, and that is even before you get to things like active booby-traps.The former would make it easy to detonate the mine (easy unless it's just offshore a city you're fond of) once the first sensor is examined. The latter would make it easy to locate the mine once the first sensor is found.

I'm not sure that the the nuclear mine would be more costly. Tactical nuclear weapons were frequently justified on cost. We tend to underestimate just how expensive even relatively unsophisticated conventional munitions can be. The nuclear mine could combine the same or a even a less advanced sensor package as that in the conventional weapon with a vastly more effective explosive charge and thus achieve a higher kill probability per mine. Hence fewer mines required to deter an opposing fleet.<snip>

So instead of a bunch of moderately costly but expendable mines, you use a bunch of less expensive sensors and one fabulously expensive atomic weapon that you can't afford to have fall into enemy hands. I can't think of anyway to link the sensors to the mine other than acoustically or via cable. The former would make it easy to detonate the mine (easy unless it's just offshore a city you're fond of) once the first sensor is examined. The latter would make it easy to locate the mine once the first sensor is found.

Historically, mines are mainly an area-denial weapon: the enemy knows that they are there, and the knowledge constrains its actions. I suspect that nuclear mining efforts would have been targeted mainly at choke points that Soviet submarines would have to transit when leaving their bases in war time. Deployment delays due to uncertainty and precautionary mine hunting at the start of a war would presumably give NATO time to concentrate its ASW ships, planes, and submarines to thwart a large-scale breakout by the Soviet submarine fleet.

jsport

what do you know about surfing Major? you're from-

- Joined

- 27 July 2011

- Messages

- 7,695

- Reaction score

- 5,665

what a modern version could provide if it had evolved ? Once again rising costs, delays, crashs, four deaths and the carrier mafia killed it.

Last edited:

hi, so while looking up info on the P6M Seamaster I come across several sources that claimed that a Curtiss wright turboramjet was the first proposed powerplant. but was cancelled do to developmental problems. does anyone know anything about this? thanks

acegeek9992

ACCESS: Confidential

- Joined

- 25 March 2021

- Messages

- 111

- Reaction score

- 76

I remember looking at the Wikipedia page that Convair also submitted a proposal for the Seamaster project, any images available?

- Joined

- 6 November 2010

- Messages

- 5,196

- Reaction score

- 5,349

acegeek9992

ACCESS: Confidential

- Joined

- 25 March 2021

- Messages

- 111

- Reaction score

- 76

Came across this reference to the P6M Seamaster having an issue with thermal expansion limiting its altitude.

“Fly By Wire Techniques” by F. L. Miller and J. E. Emfinger for the Sperry Phoenix Company, Technical Report No. AFFDL-TR-67-53, July 1967.

Temperature changes also cause friction because of unequal expansion between the airframe, which is aluminum, and the control system, which is basically steel. In aircraft traveling below Mach 2, the temperature change 18 due to altitude. The temperature differential ranges from over +120°F (+48.9°C) on the ground to -85°F (-65°C) at high altitudes. The Martin Seamaster, for example, could not fly higher than 25,000 feet because unequal expansion would lock the control system. At one time the Convair 880 had a dual cable consisting of an aluminum tubing over a spring. This system would also lock up at high altitudes. Aircraft flying at Mach 3 or higher, such as the B-70, A-11, and SST have a different temperature problem because of aerodynamic heating. At Mach 3 the skin temperature of the aircraft rises to over 500°F (260°c). Typically, the fuselage of the SST and B-70 grows 12 inches at sustained Mach 3 speeds.

“Fly By Wire Techniques” by F. L. Miller and J. E. Emfinger for the Sperry Phoenix Company, Technical Report No. AFFDL-TR-67-53, July 1967.

- Joined

- 16 April 2008

- Messages

- 9,544

- Reaction score

- 14,285

Pretty sure this isn't entirely true. I'm looking through Martin P6M Seamaster by Piet and Raithel, and it discusses test flights as high as 35,000 feet with no mention of thermal expansion problems, just the flutter and vibration issues that plagued the type throughout testing. The P6M was also supposed to test in-flight refueling at up to 30,000 feet, but didn't get past some preliminary trials before the plane was cancelled.

Firefinder

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 5 October 2019

- Messages

- 1,035

- Reaction score

- 1,861

It does depends on which version of the P6M.Pretty sure this isn't entirely true. I'm looking through Martin P6M Seamaster by Piet and Raithel, and it discusses test flights as high as 35,000 feet with no mention of thermal expansion problems, just the flutter and vibration issues that plagued the type throughout testing. The P6M was also supposed to test in-flight refueling at up to 30,000 feet, but didn't get past some preliminary trials before the plane was cancelled.

Cause you had the Prototype Straight Engine P6M-1 that did have multiple problems, one of which being the inner engine exhaust MELTING the fuselage plating on afterburner due to being to close. And two of those Crash due to control issues.

And you have Pseudo Production Version of the P6M-2 with the Engines slightly angle out to aviod that among other fixes over the first 8 prototypes, with there being 4 of those built and heavily tested themselves.

And alot of the time authors just use P6M without the dash 1 or 2 identification despite there being a far amount of difference between them. Not help by the surviving -1 being refited into -2s.

Plus these things were flying for 4 years, so there is plenty of time for that issues to be identified and fixed.

So I can see temperature expansion being an early issue that was

Similar threads

-

Commencement Bay Class Conversion Seaplane Tender (mid-1950s)

- Started by Triton

- Replies: 12

-

Martin 313 Submaster (XP7M-1): Open Ocean ASW Seaplane

- Started by Stargazer

- Replies: 13

-

‘North American General Purpose Attack Weapon’ - NAGPAW to Vigilante

- Started by Pioneer

- Replies: 68

-

Sandia Lab's Nuclear-Powered UAV Project Leaked?

- Started by flateric

- Replies: 37

-

USAF ASD 1986 FUTURE STRATEGIC AERONAUTICAL MISSION ANALYSIS

- Started by flateric

- Replies: 1