These were 1939 designs (...)

Mr Whalen, with your permission, I will add some additional details.

To put the

Chilean Navy in context, it was almost 4 decades since the purchase of its last cruiser (

Chacabuco, commissioned in 1902). In the event of a battle, Chile needed to support the battleship Latorre against the Argentine cruisers (

La Argentina unique and

Brown class) and divert fire from the Argentine battleships (

Rivadavia class).

The process of acquiring Chilean cruisers during the 1930s (to which I would add the 1920s) is very complex and complicated. In addition to establishing traditional financial mechanisms, consulting non-British shipyards and discussing alternative or delayed payment methods with foreign shipyards, it also attempted to sell Easter Island to England and applied a succession of tax regulations in the late 1930s (a digest called the "Cruisers Law").

The negotiations for Heavy Cruisers with the United Kingdom, as Alec mentions, were, in short, "boycotted". Hence the fluctuation of Chilean interests, which ranged from heavy cruisers, alternating with light cruisers to some-kind-of-medium-caliber-destroyers. The protracted negotiations simply destroyed Chilean aspirations to acquire any of these types before a war broke out. Finally it would take half a century for Chile to acquire two additional cruisers (1951 the Prat and O'Higgins).

Apparently not much documentation has survived on this subject, although some researchers mention that the contract closest to being signed was not with the British shipyards, but with the Dutch.

Leaving aside the intentions to acquire Heavy Cruisers and returning to the

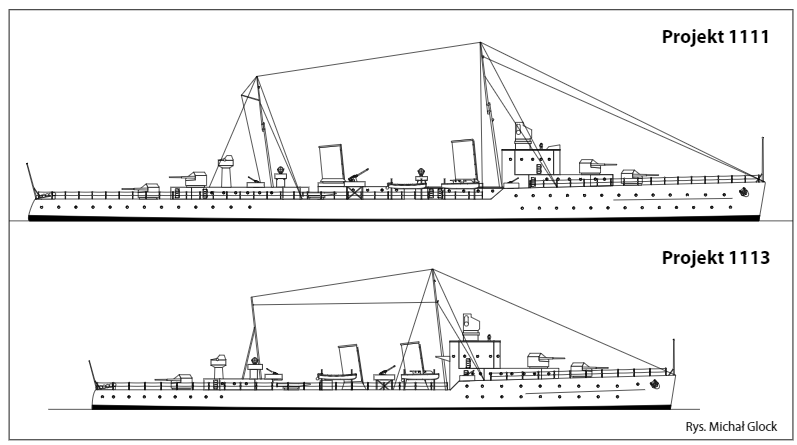

Vickers-Armstrong 1111 and 1113 designs, these are from August 1939.

In the previous months the Chilean Navy was looking for something that would combine the attributes of the French

Mogador and the Dutch

Tromp. The shipyards of reference seem to have been the British and Italian ones, although there are records of others. The above destroyers (or light fast cruisers) had respectively an 8-gun 139mm deck with a standard displacement of 3,000 tons and a speed of 39 knots and a 6-gun 149mm deck with a standard displacement of 3,400 tons and a speed of 33 knots. The ships to be acquired would also have catapults and torpedo tubes. Protection seems to have been little considered, but varies with the negotiations.

As seen, the

Vickers 1113 design is the one that most closely matches the previous ones by means of standard British technology.

Regarding the

Vickers 1111, my interpretation is that the 1111 design was not an alternative to the 1113, but rather a complement. It seems to me this design has both an "anti-aircraft" and "counter-destroyer" cruiser approach, as its battery does not seem competent against the Argentine battleships (and perhaps cruisers). For more details the Argentine Navy at that time had 7 modern destroyers (

Buenos Aires class), 5 relatively modern destroyers (

Mendoza and

Cervantes classes), 4 older modified destroyers (

Catamarca and

Córdoba classes) and a total of 118 53cm tubes with Whitehead torpedoes (similar to

this) capable of threatening the battleship Latorre (

bulge and belt). For its part, Chile had 6 relatively modern destroyers (

Serrano class) and 2 older modified destroyers (

Almirante/Lynch class) to confront them. And Chile no longer had any cruisers, with the exception of the Chacabuco (not yet modernized/converted into a school). The Vickers 1111 could have been an interesting solution.

Apparently Brown associated with Vickers-Armstrong created a later offer as

a derivative design with 2 additional guns (a hybrid between the 1111 and the 1113?), but no details/schemes seem to have survived.

A brief reading about these offers can be found in the "Okręty Wojenne" magazine (Year 2011, Number 106).

The publication "British Fiji Class Cruisers and their Derivates. Design, Development and Performance" mentions

ADM 116/3920 and

ADM 116/3921 as the "British perspective on Chile’s attempts to acquire new cruisers". If anyone can access this, please share the details.

Regards