blackkite

Don't laugh, don't cry, don't even curse, but.....

- Joined

- 31 May 2007

- Messages

- 8,817

- Reaction score

- 7,691

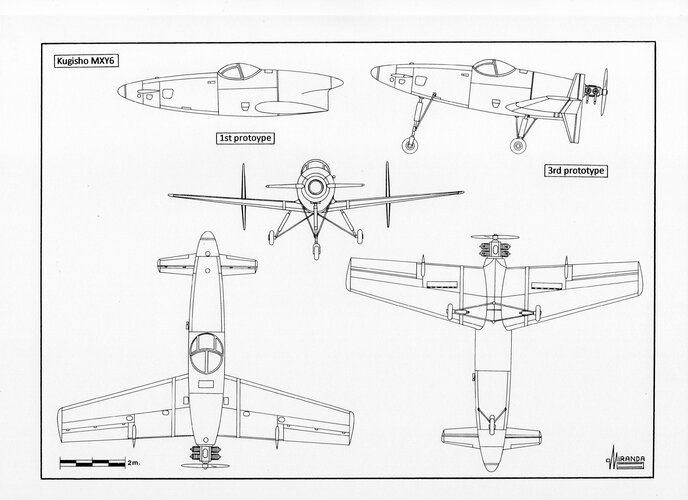

There is a theory that there was a concept to equip the Shinden with a jet engine and call it "Shinden Kai" (J7W2). The basis for this theory is an contribution written by Kunitake Kiyohara, former deputy chief of the 1st Design Division of the Kyushu Airplane Design Department, in an aviation magazine.

In his contribution, Kiyohara wrote, "On June 5, 1944, at the 'Shinden' Project Request Study Group held at the Kugisho, or as an instruction afterwards, a member of the Kugisho's engine staff said as indication to me, "Proceed with the design of modified Shinden using a jet engine. The jet engine to be installed in the modified Shinden will have a ground static thrust of 900 kg, which is equivalent to almost 3,000 HP, and the expected speed will be about 420 kt (780 km/h). However, this modified Shinden requires a take-off auxiliary rocket, which we want to treat as an overload condition."

In his contribution, Kiyohara also wrote, "I thought that the jet engine to be installed in the improved Shinden model would be a Ne-130 jet engine that was being prototyped at the Ishikawajima Shibaura turbine, and I thought that the dogfight era was finally over. Considering the layout of the Shinden's engine, I thought it would not be so difficult to replace it with a jet engine. I was excited by this plan and I wanted to realize as soon as possible. In the end, this plan did not come to fruition, but the twin-engine jet attack aircraft "Kikka" designed by Nakajima Aircraft was prototyped by Kyushu Aircraft, and the war ended when the first aircraft was almost completed.

However, no other specific records have been found of jet engine installed modified Shinden In addition, Mitsuo Nishimura, who served as the chief of Shinden's power outfitting team, also admitted that there was a plan for jet Shinden, but also testified that "no concrete progress had been made" toward its realization. The progress of the development of the Ne-130, a prototype jet engine that was scheduled to be installed at the time, was only at the stage of full-scale testing near the end of the war, and it was not in a situation where it could actually be operated.

The predecessor of the Ne-130, the Ne-20, had a variety of fatal flaws, which shortened its endurance life to only 15 hours at full power. This defect was exposed even during the test flight of Kikka, which was being developed in parallel with Shinden, and it is said that it was not going to be solved. This defect occurred not only in the Ne-20 but also in the Ne-130 under development, and of course it was not in a situation where it could be installed on the Shinden.

Furthermore, at the end of the war, Japan was almost depleted of rare metals (nickel, chromium, etc.) for making heat-resistant metals that were indispensable for jet engines, and the development of alternative metals with high heat resistance due to a lack of resources for exhaust turbines was a major problem. Therefore, even if a prototype jet engine was completed, mass production would have been almost impossible.

In his contribution, Kiyohara wrote, "On June 5, 1944, at the 'Shinden' Project Request Study Group held at the Kugisho, or as an instruction afterwards, a member of the Kugisho's engine staff said as indication to me, "Proceed with the design of modified Shinden using a jet engine. The jet engine to be installed in the modified Shinden will have a ground static thrust of 900 kg, which is equivalent to almost 3,000 HP, and the expected speed will be about 420 kt (780 km/h). However, this modified Shinden requires a take-off auxiliary rocket, which we want to treat as an overload condition."

In his contribution, Kiyohara also wrote, "I thought that the jet engine to be installed in the improved Shinden model would be a Ne-130 jet engine that was being prototyped at the Ishikawajima Shibaura turbine, and I thought that the dogfight era was finally over. Considering the layout of the Shinden's engine, I thought it would not be so difficult to replace it with a jet engine. I was excited by this plan and I wanted to realize as soon as possible. In the end, this plan did not come to fruition, but the twin-engine jet attack aircraft "Kikka" designed by Nakajima Aircraft was prototyped by Kyushu Aircraft, and the war ended when the first aircraft was almost completed.

However, no other specific records have been found of jet engine installed modified Shinden In addition, Mitsuo Nishimura, who served as the chief of Shinden's power outfitting team, also admitted that there was a plan for jet Shinden, but also testified that "no concrete progress had been made" toward its realization. The progress of the development of the Ne-130, a prototype jet engine that was scheduled to be installed at the time, was only at the stage of full-scale testing near the end of the war, and it was not in a situation where it could actually be operated.

The predecessor of the Ne-130, the Ne-20, had a variety of fatal flaws, which shortened its endurance life to only 15 hours at full power. This defect was exposed even during the test flight of Kikka, which was being developed in parallel with Shinden, and it is said that it was not going to be solved. This defect occurred not only in the Ne-20 but also in the Ne-130 under development, and of course it was not in a situation where it could be installed on the Shinden.

Furthermore, at the end of the war, Japan was almost depleted of rare metals (nickel, chromium, etc.) for making heat-resistant metals that were indispensable for jet engines, and the development of alternative metals with high heat resistance due to a lack of resources for exhaust turbines was a major problem. Therefore, even if a prototype jet engine was completed, mass production would have been almost impossible.