The métallos definitely considered themselves skilled workers, which is part of why unionization didn't get very far in the factories.In a 1930s-or-before US factory, production of a complex assembly...an engine or airframe...might have been organized on a team-cell basis. A small group of workers, each with multiple skills approaching the level of craftsman, would build that assembly from beginning to completion. Then they'd build another one. There might be multiple cells in parallel, each turning out a slow series of completed assemblies.

I think quite possibly French aircraft-industry manufacturing mostly was organized on that basis in the late 1930s.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

French airforce from 1935 to 1940-41?

- Thread starter tomo pauk

- Start date

I think that's rather the point here. Arjun and I are both curious about the sourcing of information that you're providing.my intention is to provide unusual but authentic information to help make their stories more credible.

I am saddened that you don't consider my contributions "significant." I have tried to present specific information that corrects errors earlier in the topic, or that expands on previousinformation. Does anyone benefit from simply leaving errors in place, so that search engines and later reader come up with the wrong information?

However, if you find asking specific questions to be "overly critical," the only way to ensure that information is authentic is to examine sources. When the sources do not support the information that was given, the information cannot be considered "authentic."

I've been reading sam40.fr for a long time. There's an article about French aeronautical production methods (http://sam40.fr/1935-1940-la-constr...ancaise-au-defi-dune-revolution-industrielle/) that discusses the French engineer, and exile, Henry Guerin. Guerin developed methods for literally stamping out airplanes at Douglas, which was used here in El Segundo to build the SBDs that destroyed all of the Japanese carriers at Midway. (I live within walking distance of where the DB-7 carrying the French observer crashed during a demonstration flight, causing a national scandal.)

Earlier this year, I discovered that my father's first job after moving to California was working for Henry Guerin! Guerin had left Douglas several years before and he was the person who interviewed and hired my father to work on the first aerospace honeycomb structures. My father, who was 18 or 19, was simply told to get on with it, with almost no direction. It was a small company, so Guerin was his direct boss.

Learning this was pretty shocking!

That's awesome ! Are you french by any way ?

Sam40.fr is, indeed, very good. That blog has information seldom seen elsewhere. Drix too, but he is biased, with too many axes to grin.

Truly was an uphill battle to fix 1930's France...I'm still not sure if even a victory of the Tardieu faction in the early 30s would materially improve things.

That's an understatement ! I have very mixed feelings about the whole thing. Sometimes I think May 1940 was a "necessary evil" to burn and raze to the ground that deeply rotten 3rd Republic France. Alas, only thinking that brings the shame of Vichy and their death warrant of 80 000 french jews, Vel' d'Hiv included.

1940 cataclysm - maybe.

Vichy byproduct - NO WAY.

That's probably how I ended at the FTL forum 15 years ago, although it is not a Teletubbies best case by any mean. WWII carnage and nazi horrors still happen.

Elan Vital

ACCESS: Secret

- Joined

- 6 September 2019

- Messages

- 329

- Reaction score

- 751

Quite interesting when people now mainly remember the late 30's aero unions for allegedly obstructing proper production. One wonders how many such constructive proposals were made both in 1936 and more generally before and after, but were not taken (at least not straight away).The commitment to machining methods of the "Birkigt method" of manufacturing (the term used by Hispano-Suiza) blocked the rapid expansion of engine production. It required exceptional skill from the machine tool operator, and that's not something that can be trained up in 6 months. Birkigt was also wedded to unique tools for every part, which required a lot of time to produce.

Of course, anything that bottlenecks engine production bottlenecks aircraft production.

Interestingly, in 1936 the union demands included massive investments in new machine tools (apparently many dated from the Great War) and having the plant open for a half day on Saturdays so that the workers could come in and perform maintenance on their tools--without pay.

Not a bit. I never even took a French course in school, so my ability to read French slowly and painfully is self-taught. My sister did marry a Swiss French watchmaker, so she learned some and my nephews are fully bilingual.That's awesome ! Are you french by any way ?

I do wish Drix would give sources.Drix too, but he is biased, with too many axes to grin.

I suspect that the "deep rot" has been overstated. Petain's government had a strong inventive to excoriate the 3rd Republic, the PCF and others on the left were happy to critique the right-wing's activities (such as the attempted coup), and the post-war government had the incentive to buttress its legitimacy by pointing out the problems of the 3rd Republic and how it was better.That's an understatement ! I have very mixed feelings about the whole thing. Sometimes I think May 1940 was a "necessary evil" to burn and raze to the ground that deeply rotten 3rd Republic France.

Other democracies have overcome rot through reform. In the British case, the reform of the "rotten boroughs" comes to mind. While the 3rd Republic had multiple problems that it needed to resolve, electoral reform and some changes to the way the parliament functioned could have gone a long way. For example, forcing an election when a government fell would have stabilized governments and ministries by removing the incentive for constant intriguing and changing alliances.

There are some very nice histories of the French labor movement leading up to the Popular Front, during it, and after, but only one extensive work in English (available online, fortunately). Reading through the demands, almost all of them are things we take for granted today. I mean, paid vacation?Quite interesting when people now mainly remember the late 30's aero unions for allegedly obstructing proper production. One wonders how many such constructive proposals were made both in 1936 and more generally before and after, but were not taken (at least not straight away).

That's not to say that strikes never hurt production or that there was no obstructionism.

Of course, in the aftermath of the collapse, Petain's government (which was very anti-union and saw communists around every corner) and the industrialists had an overwhelming incentive to blame everything on unions, communists, and sabotage. And they got the first crack at writing the history. Later, DeGaulle was struggling with the PCF for dominance in liberated France and post-war. These domestic political contests created more incentives to escape blame and direct it onto others. Participants in this thread have pointed out some of the problems that the manufacturers caused. SAM40.fr has some good work on the rapid expansion of the aviation sector and the number of new workers coming in. This always causes quality problems. Along with pressure to produce aircraft as quickly as possible! So much of what was attributed to sabotage was certainly haste, accidents, corner-cutting, and inexperience.

By the way, I've been going very easy in the PCF. While I think that they've received blame out of proportion to their real influence, I have great criticisms of them as well, not least of which is their lack of policy independecen, taking direction from the Comintern. I am personally deeply disdainful of communism as a political and economic system in practice. Marxism is occasionally a useful framework for analysis, but not as a guide to policy.

Elan Vital

ACCESS: Secret

- Joined

- 6 September 2019

- Messages

- 329

- Reaction score

- 751

Do you have a link to that English work?There are some very nice histories of the French labor movement leading up to the Popular Front, during it, and after, but only one extensive work in English (available online, fortunately). Reading through the demands, almost all of them are things we take for granted today. I mean, paid vacation?

That's not to say that strikes never hurt production or that there was no obstructionism.

Of course, in the aftermath of the collapse, Petain's government (which was very anti-union and saw communists around every corner) and the industrialists had an overwhelming incentive to blame everything on unions, communists, and sabotage. And they got the first crack at writing the history. Later, DeGaulle was struggling with the PCF for dominance in liberated France and post-war. These domestic political contests created more incentives to escape blame and direct it onto others. Participants in this thread have pointed out some of the problems that the manufacturers caused. SAM40.fr has some good work on the rapid expansion of the aviation sector and the number of new workers coming in. This always causes quality problems. Along with pressure to produce aircraft as quickly as possible! So much of what was attributed to sabotage was certainly haste, accidents, corner-cutting, and inexperience.

By the way, I've been going very easy in the PCF. While I think that they've received blame out of proportion to their real influence, I have great criticisms of them as well, not least of which is their lack of policy independecen, taking direction from the Comintern. I am personally deeply disdainful of communism as a political and economic system in practice. Marxism is occasionally a useful framework for analysis, but not as a guide to policy.

Anyway, I'd certainly agree that the demands made sense. It's hard to not want to maximise working hours when you look at WW2 production needs, but I've seen many contemporary cases where too many hours only degraded performance due to the workers being tired. Plus I have no doubt that some of the "free time" in case of lower hours would actually be spent on maintenance and organisation to improve overall productivity without being as hard physically and mentally as the main work.

I'm really curious though as to what other proposals the workers made to improve productivity without degrading their condition, it's logical that skilled workers would know what organisational or technical changes would be needed to work produce more aircrafts.

I don't think so. I've seen "neutral" point of views that pointed how hopeless the 3rd Republic was, in its last decade at least. The 1930's were politically ugly at every level.I suspect that the "deep rot" has been overstated. Petain's government had a strong inventive to excoriate the 3rd Republic, the PCF and others on the left were happy to critique the right-wing's activities (such as the attempted coup), and the post-war government had the incentive to buttress its legitimacy by pointing out the problems of the 3rd Republic and how it was better.

...as for Pétain and Laval, the Riom trial (1942) was to be their triumph against both the late 3rd Republic and french military... except the accused had no problem pointing the Vichysts had been and still were part of the quagmire. And the trial had to be stopped in a hurry and in shame.

And then the 4th republic got 25 governments in 12 years, a remarquable once-every-six-month record.

France learned the art of viable Republics the hard way, for sure. It is a bit like the legendary swamp castle, of Monty Pythons fame.

Chapman, Herrick. State Capitalism and Working-Class Radicalism in the French Aircraft Industry. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1991 1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft9m3nb6g1/

Alternative URL: https://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft9m3nb6g1;brand=ucpress

I also recommend Le PCF et la défense nationale à l'époque du Front populaire (1934-1939) by Georges Vidal. Not so concerned with union demands, but worth reading for more general background.

The funniest incident in that article is when a study commission of Popular Front deputies, including some from the PCF, go on an inspection tour of the Maginot Line. I imagine that the generals must have been apoplectic at the idea of communists getting information on the Maginot Line ...

In any case, the PCF deputies are appalled by what they find. The artillery armament of the forts is wildly insufficient, both in number and in caliber, and they call for a great increase! (I believe that the guns were restricted to 75mm at the same, possibly with a handful of heavier guns.)

Alternative URL: https://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft9m3nb6g1;brand=ucpress

I also recommend Le PCF et la défense nationale à l'époque du Front populaire (1934-1939) by Georges Vidal. Not so concerned with union demands, but worth reading for more general background.

The funniest incident in that article is when a study commission of Popular Front deputies, including some from the PCF, go on an inspection tour of the Maginot Line. I imagine that the generals must have been apoplectic at the idea of communists getting information on the Maginot Line ...

In any case, the PCF deputies are appalled by what they find. The artillery armament of the forts is wildly insufficient, both in number and in caliber, and they call for a great increase! (I believe that the guns were restricted to 75mm at the same, possibly with a handful of heavier guns.)

A Tentative Fleet Plan

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 9 April 2018

- Messages

- 1,206

- Reaction score

- 2,804

Every fort built or heavily modernised since the 1885 torpedo shell crisis have had a minimal safety armament, intended only to protect the fort and intervals between it and the next fort in line, and to prevent the enemy from encircling them, and forcing them to set up their seige batteries at range. In the Séré de Rivières system heavier artillery would be in the intervals, protected by turrets and traditore batteries of the forts, and by infantry works with minimal armament (although they later began to grow in size and armament, becoming very similar to forts, with machine gun turrets, 75mm guns in retracting turrets and traditore batteries, and potentially ditches flanked by counterscarp casemates).The funniest incident in that article is when a study commission of Popular Front deputies, including some from the PCF, go on an inspection tour of the Maginot Line. I imagine that the generals must have been apoplectic at the idea of communists getting information on the Maginot Line ...

In any case, the PCF deputies are appalled by what they find. The artillery armament of the forts is wildly insufficient, both in number and in caliber, and they call for a great increase! (I believe that the guns were restricted to 75mm at the same, possibly with a handful of heavier guns.)

The Maginot line was essentially a further development of this system, with the forts and infantry works being broken up into multiple blocks potentially with a ditch flanked by counterscarp casemates (although this was dropped fairly early on due to cost, only a couple of works receiving partially complete ditches).

The Maginot Line was intended to receive 155mm Howitzers and long-range 145mm guns for counter-battery fire, but given the fact that they would be supported by heavier artillery from other formations, including the heavy railway guns of the ALVF, these were hardly necessary, especially since the Old Fronts with the Artillery works didn't actually fall until they were convinced to surrender after the armistice.

The New Fronts were a different story, not being armed with anything larger than infantry weapons.

The Maginot line by itself was very well done and thought. It is kind of vibrant proof that not everything was deeply rotten in the 1930's 3rd Republic & French military era. I give this to them.

The mistake of course was betting way too much on Belgium neutrality and the Ardennes. The weak links were Huntziger and Corap armies there.

Last fort on the northern tip of the Maginot line was La Ferté: at the crossroads of Luxembourg, France and Belgium borders. As a matter of fact, when imagining the Sickle Cut, Manstein and his goons picked that exact place for their breakthrough. They just added a 15 km safety margin, corresponding to La Ferté larger guns maximum range. German ruthless efficiency, as its best - unfortunately.

They also knew that Corap and Hunziger armies stretched over the next 100 km (up to Blanchard and Billote much more formidable armies) were weak: underarmed. The other point they picked for their breakthrough was the junction of Corap and Huntziger armies.

The Sickle cut was a masterpiece just for that. A 100 km wide corridor for 7 panzers: one flank just outside the Maginot line, the other flank right into Corap & Huntziger.

The mistake of course was betting way too much on Belgium neutrality and the Ardennes. The weak links were Huntziger and Corap armies there.

Last fort on the northern tip of the Maginot line was La Ferté: at the crossroads of Luxembourg, France and Belgium borders. As a matter of fact, when imagining the Sickle Cut, Manstein and his goons picked that exact place for their breakthrough. They just added a 15 km safety margin, corresponding to La Ferté larger guns maximum range. German ruthless efficiency, as its best - unfortunately.

They also knew that Corap and Hunziger armies stretched over the next 100 km (up to Blanchard and Billote much more formidable armies) were weak: underarmed. The other point they picked for their breakthrough was the junction of Corap and Huntziger armies.

The Sickle cut was a masterpiece just for that. A 100 km wide corridor for 7 panzers: one flank just outside the Maginot line, the other flank right into Corap & Huntziger.

The Curtiss H-75 did wonders, even with the wrong pilot tactics and too light armement. The bombers were pretty good too - Martin 167F and DB-7 - but they came too little, too late. None of them came close from the main fighting at the right time: the Ardennes, May 10 - 15. For example the first DB-7 unit that entered the fight came from Normandy... on May 18.

Main advantage of american aircraft: they came complete and their engines worked well. Unlike french types which lacked propellers, radios, bombsights... and workable engines.

With perfect hindsight, France should have bought earlier, more US bombers.

They had another advantage: they filled the gap between a) the Breguet 693 attack planes at tree top level, that got decimated by Flak; and b) the LeO-451 & Amiot 350 built for night city bombing: not for daylight attacks on panzers. France had one such bomber, the MB-175 but it came too late.

During the Weygand line fighting early June the DB-7 and Martin 167F proved they were the right combination for daylight bombing and attack of german forces. As fast as a Breguet 693 but better defended, with more powerful engines and carrying more bombs; yet smaller and more agile than LeO and Amiots. They were in the right spot.

Instead of building 1100 Potez 63, slow and vulnerable, plus 200 - something Breguet 690- ; France should have invested more in MB-175, DB-7 and Martin 167. An advanced striking force similar to Great Britain numerous Blenheim and Battle, albeit with better planes.

Main advantage of american aircraft: they came complete and their engines worked well. Unlike french types which lacked propellers, radios, bombsights... and workable engines.

With perfect hindsight, France should have bought earlier, more US bombers.

They had another advantage: they filled the gap between a) the Breguet 693 attack planes at tree top level, that got decimated by Flak; and b) the LeO-451 & Amiot 350 built for night city bombing: not for daylight attacks on panzers. France had one such bomber, the MB-175 but it came too late.

During the Weygand line fighting early June the DB-7 and Martin 167F proved they were the right combination for daylight bombing and attack of german forces. As fast as a Breguet 693 but better defended, with more powerful engines and carrying more bombs; yet smaller and more agile than LeO and Amiots. They were in the right spot.

Instead of building 1100 Potez 63, slow and vulnerable, plus 200 - something Breguet 690- ; France should have invested more in MB-175, DB-7 and Martin 167. An advanced striking force similar to Great Britain numerous Blenheim and Battle, albeit with better planes.

Last edited:

Sorry. I meant French aviation industry and procurement. I corrected it.The Curtiss H-75 did wonders, even with the wrong pilot tactics and too light armement. The bombers were pretty good too - Martin 167F and DB-7 - but they came too little, too late. None of them came close from the main fighting at the right time: the Ardennes, May 10 - 15. For example the first DB-7 unit that entered the fight came from Normandy... on May 18.

Main advantage of american aircraft: they came complete and their engines worked well. Unlike french types which lacked propellers, radios, bombsights... and workable engines.

With perfect hindsight, France should have bought earlier, more US bombers.

They had another advantage: they filled the gap between a) the Breguet 693 attack planes at tree top level, that got decimated by Flak; and b) the LeO-451 & Amiot 350 built for night city bombing: not for daylight attacks on panzers. France had one such bomber, the MB-175 but it came too late.

During the Weygand line fighting early June the DB-7 and Martin 167F proved they were the right combination for daylight bombing and attack of german forces. As fast as a Breguet 693 but better defended, with more powerful engines and carrying more bombs; yet smaller and more agile than LeO and Amiots. They were in the right spot.

Instead of building 1100 Potez 63, slow and vulnerable, plus 200 - something Breguet 690- ; France should have invested more in MB-175, DB-7 and Martin 167. An advanced striking force similar to Great Britain numerous Blenheim and Battle, albeit with better planes.

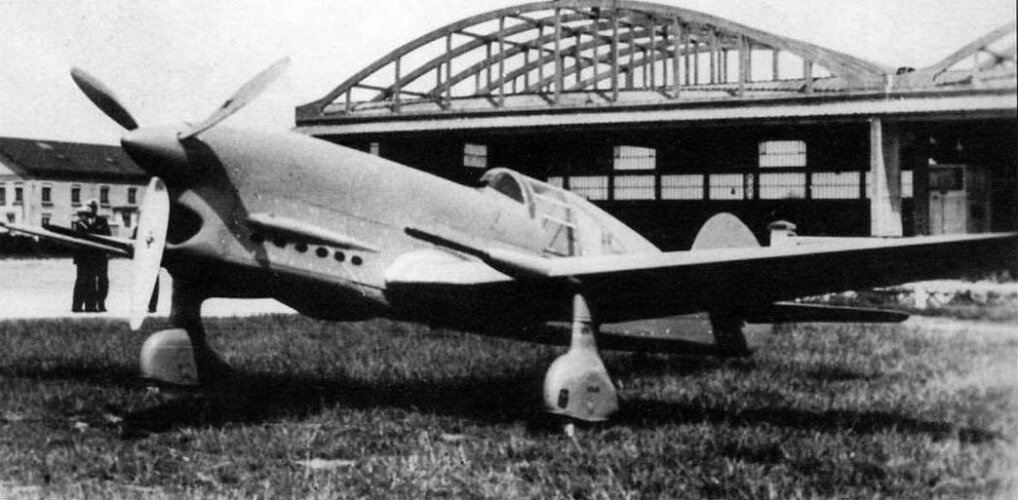

For what it's worth, I've always thought that the Caudron C.710 with fixed gear and twin 20mm cannons was a huge missed opportunity as a dedicated low-level fighter. It was already flying in 1936 and doing 455 km/h (283 mph; 246 kn) at 4,000 m (13,000 ft) with the 450 HP Renault 12-cylinder. It's 20/20 hindsight, of course, but if there had been a decision to just refine that design with the better 500 HP engine and tweak it for fast production, the Armée de l'Air could have had hundreds of little Stuka killers/bomber hunters while leaving the 109s and 110s to the more capable fighters. With armor-piercing ammo and light anti-personnel bombs, the 710s could even have done some serious damage to German armor (mostly Panzer Is and IIs during the Battle of France) and infantry. At the end of the day, the French were let down by politics bureaucracy and greed when it came to aircraft production, not any fundamental problems with their aircraft designs.

Attachments

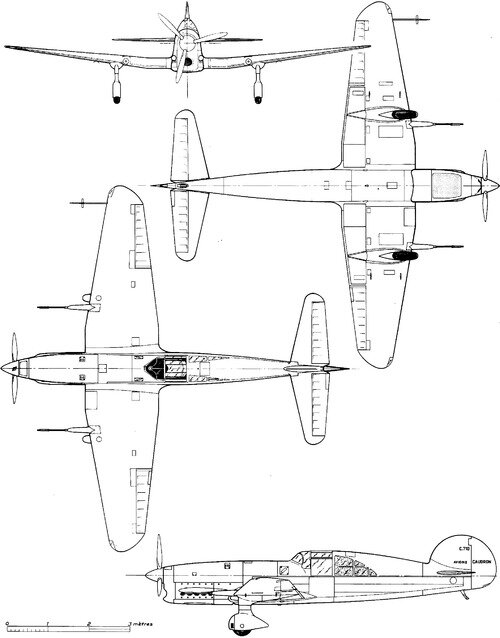

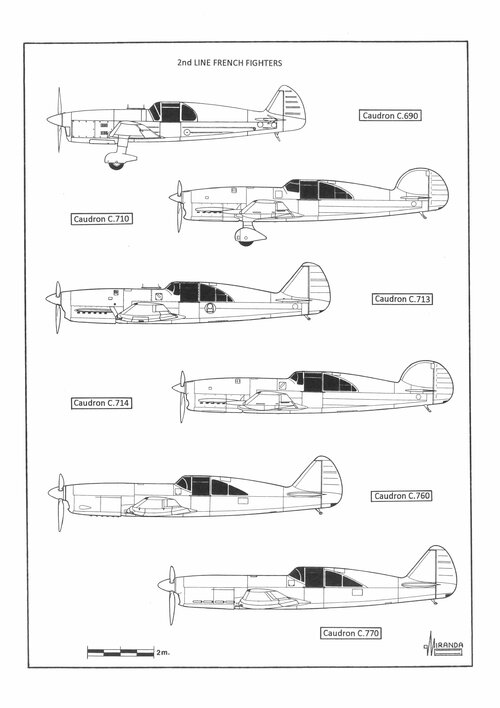

On July 12, 1934, the Service Technique de l’Aéronautique laid down the Programme Technique de Chasseur Léger C.1, a specification for a light weight interceptor with a maximum speed of 400 kph and armed with four machine guns. The original specification was amended in August 22 dividing it in two categories: one for aircraft powered by 800-1,000 hp engines, armed with a cannon and two machine guns, and another for 450-500 hp engines and two cannons. On 17 December 1934 the maximum speed rose to 450 kph and on 16 November 1935 to 500 kph. The winner of the first category was the Morane-Saulnier M.S.405, winning the production of the 860 hp Hispano-Suiza H.S.12 Y engines.For what it's worth, I've always thought that the Caudron C.710 with fixed gear and twin 20mm cannons was a huge missed opportunity as a dedicated low-level fighter. It was already flying in 1936 and doing 455 km/h (283 mph; 246 kn) at 4,000 m (13,000 ft) with the 450 HP Renault 12-cylinder. It's 20/20 hindsight, of course, but if there had been a decision to just refine that design with the better 500 HP engine and tweak it for fast production, the Armée de l'Air could have had hundreds of little Stuka killers/bomber hunters while leaving the 109s and 110s to the more capable fighters. With armor-piercing ammo and light anti-personnel bombs, the 710s could even have done some serious damage to German armor (mostly Panzer Is and IIs during the Battle of France) and infantry. At the end of the day, the French were let down by politics bureaucracy and greed when it came to aircraft production, not any fundamental problems with their aircraft designs.

In the second category were competing small manufacturers and designers of racer airplanes experienced in obtaining the maximum speed with minimum power, often using self-made engines. The success achieved by the Caudron racers, encourage designer Marcel Riffard to build the C.710 and C.713 prototypes, two wooden, cannon-armed, light fighters capable of flying to 455-470 kph powered by a 450 hp Renault 12 R.01 engine. In December 1937 l’Armée de l’Air dismissed its serial construction in favor of the Arsenal VG 30, much faster and with better climb rate.

In November 1938, to meet the requirements of Plan V, l’Armée de l’Air ordered the production of 200 units of the C.R. 714 model, an aerodynamically improved version, with a 450 hp Renault 12 R.03, twelve-cylinder, air-cooled, inverted-Vee engine and four MAC 1934 M39 machine guns. The order was later reduced to only 20 aircraft when all the spruce stocks were assigned to the massive construction program of the Arsenal VG 33.

In January 1940 the C.R. 714 were handed over to l’Armée de l’Air who used them as advanced trainers at l’École de Chasse et d’Instruction Polonaise. The G.C. I/145 was formed during the Battle of France with M.S. 406 and C.R. 714 fighters piloted by Poles who claimed the destruction of four Bf 109 and four Do 17. The formula was perfectioned with the C.R. 760 and C.R. 770 prototypes, powered by 730-800 hp engines and armed with six MAC, but both were destroyed to prevent their capture by the Germans.

Attachments

For what it's worth, I've always thought that the Caudron C.710 with fixed gear and twin 20mm cannons was a huge missed opportunity as a dedicated low-level fighter. It was already flying in 1936 and doing 455 km/h (283 mph; 246 kn) at 4,000 m (13,000 ft) with the 450 HP Renault 12-cylinder. It's 20/20 hindsight, of course, but if there had been a decision to just refine that design with the better 500 HP engine and tweak it for fast production, the Armée de l'Air could have had hundreds of little Stuka killers/bomber hunters while leaving the 109s and 110s to the more capable fighters.

Up-engine the Caudrons with the G&R 14M? Engine power is incresed in a major way (probably we might get to above 500 km/h? - supposedly the MB.700 was good for 550 km/h), and weight is kept in check. Yes, the radial will add some drag, however the 14M was pretty small engine to begin with.

BTW - leaving the more menacing enemy fighter to the own better fighters does not work, since it requires the enemy to cooperate, and Germans were - for their reasons - not willing to cooperate with many people back in ww2.

With armor-piercing ammo and light anti-personnel bombs, the 710s could even have done some serious damage to German armor (mostly Panzer Is and IIs during the Battle of France) and infantry.

Good point on the powerful 20mm cannons being a great anti-armor asset in 1940. It will require some foresight on the part of AdA to see that opportunity and supply the AP ammo, though.

At the end of the day, the French were let down by politics bureaucracy and greed when it came to aircraft production, not any fundamental problems with their aircraft designs.

French politics were to blame to a lot of things.

Their aircraft and aero engines were also behind what Germans were making, though, so let's not save the industry from the hook. The mass-produced Potez 63 series tried to do many things, while being bad in doing any that is combat-related. MS.406 was obsolete when compared with Hurricane I, Spitfire or Bf 109E, despite being of same generation. HS 12Y was a full generation behind the Merlin or DB 601. The G&R 14M was a nice, small engine, but what was needed for the 1st line A/C was a powerful radial (talk 1300 HP, and hopefully 1500), not something good for 700 HP.

Whoever approved the HS starts making radial engines was deserving the nice, hot cell in the Devil's Island prison.

That MS.406 was harder to mass produce than the 2-engined Potet 63 series is mind-boggling.

Thanks, @Justo Miranda and @tomo pauk for your comments. I am aware of the history of the Caudron series and the Arsenal VG series, which sadly proved to be too little, too late. I am also aware of the shortcomings and lack of planning and urgency that led to the overall too little, too late aspect of the whole French war effort at the time. I do want to emphasize that the C.710 was not a great fighter, not even a good fighter, but I see it as a potentially effective emergency fighter in the spirit of the Miles M.20 not long afterwards on the other side of the Channel, also of wooden construction wth fixed gear. And yes, I agree completely that a 700 hp G&R 14M could have completely transformed the C.710, probably not improving top speed too much but greatly improving acceleration and climb rate.

Last edited:

France lacked three things

-a Merlin

-standardize the fighter fleet with a Hurricane

-standardize the fighter fleet with a Spitfire

Talking about the MS-406, the alternative was the Loire Nieuport 160 series, and it had far, far better potential. The circumstances in which it lost to the MS-405 are pretty unclear, and smells like typical decaying 3rd Republic corruption and political games.

-a Merlin

-standardize the fighter fleet with a Hurricane

-standardize the fighter fleet with a Spitfire

Talking about the MS-406, the alternative was the Loire Nieuport 160 series, and it had far, far better potential. The circumstances in which it lost to the MS-405 are pretty unclear, and smells like typical decaying 3rd Republic corruption and political games.

The MS-406 is a good plane. Potentially better than the Hurricane. The problem is different. At the time of its appearance, it was clearly superior to modern versions of the Bf-109. But when the Moran went into battle, it was the same, and the Messerschmidt was already on its fifth major and two more minor modifications. If it had gone at least half of this way, it would have been a first-class fighter. Also with an engine. The Hispano-Suiza was accelerated to 1700 hp. if I am not mistaken. Up to 1100 by the end of the campaign in France. The trouble is that France mobilized late, and the Hispano-Suiza 12 was a civilian engine with a civilian approach to resource and reliability. Therefore, it gave 860 hp. And during the war, sometimes for the sake of an increase of 50 forces they agreed to an engine with a resource of 25 hours. Even in the underdeveloped USSR, with minor modifications, it was brought to 1290 hp take-off power and significantly modified to 1600 hp.

By the way, both the Yak-1/9 and the LaGG-3/La-5 were born from the program to launch the Soviet analogue of the Codron С-714 into production.

By the way, both the Yak-1/9 and the LaGG-3/La-5 were born from the program to launch the Soviet analogue of the Codron С-714 into production.

In January 1940 the C.R. 714 were handed over to l’Armée de l’Air who used them as advanced trainers at l’École de Chasse et d’Instruction Polonaise. The G.C. I/145 was formed during the Battle of France with M.S. 406 and C.R. 714 fighters piloted by Poles who claimed the destruction of four Bf 109 and four Do 17. The formula was perfectioned with the C.R. 760 and C.R. 770 prototypes, powered by 730-800 hp engines and armed with six MAC, but both were destroyed to prevent their capture by the Germans.

What would those experienced Polish pilots have been able to do with the two 20mm cannon of a refined, 500 hp C.710 or better yet a 700 hp radial version?

The MS-406 is a good plane. Potentially better than the Hurricane. The problem is different. At the time of its appearance, it was clearly superior to modern versions of the Bf-109. But when the Moran went into battle, it was the same, and the Messerschmidt was already on its fifth major and two more minor modifications. If it had gone at least half of this way, it would have been a first-class fighter. Also with an engine. The Hispano-Suiza was accelerated to 1700 hp. if I am not mistaken. Up to 1100 by the end of the campaign in France. The trouble is that France mobilized late, and the Hispano-Suiza 12 was a civilian engine with a civilian approach to resource and reliability. Therefore, it gave 860 hp. And during the war, sometimes for the sake of an increase of 50 forces they agreed to an engine with a resource of 25 hours. Even in the underdeveloped USSR, with minor modifications, it was brought to 1290 hp take-off power and significantly modified to 1600 hp.

By the way, both the Yak-1/9 and the LaGG-3/La-5 were born from the program to launch the Soviet analogue of the Codron С-714 into production.

The Morane has serious deffects, like a dumbarse radiator : if extended, it slowed down the plane, if retracted, the engine overheated. Also its production was way too slow, it passed the 1000 treshold only because it started production so early. MS-406 somewhat played the same role as the Hurricane and P-40, except it lacked engine power.

Yet the Swiss and Fins managed to do well with it. Switzerland notably turned a donkey (D-3800) into a thoroughbread (D-3801 / D-3802). In France was a plan to turn the Moranes into MS-410 with a bag of improvements. But, there is the rub: massively plagued by inefficiencies, at every level, plus panicking, France did not prioritize the MS-410 program. Considerable amounts of time, money and energy were wasted chasing dead ends.

Bottom line: France was unable to do this in time. https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morane-Saulnier_MS.406#Le_D-3801

Elan Vital

ACCESS: Secret

- Joined

- 6 September 2019

- Messages

- 329

- Reaction score

- 751

I remember reading on the Sam40 blog that the end of MS-406 production in 1940 was a little premature considering the lack of modern planes and the delays in D520 deliveries, and the fact it would incentivize the MS-410 program.The Morane has serious deffects, like a dumbarse radiator : if extended, it slowed down the plane, if retracted, the engine overheated. Also its production was way too slow, it passed the 1000 treshold only because it started production so early. MS-406 somewhat played the same role as the Hurricane and P-40, except it lacked engine power.

Yet the Swiss and Fins managed to do well with it. Switzerland notably turned a donkey (D-3800) into a thoroughbread (D-3801 / D-3802). In France was a plan to turn the Moranes into MS-410 with a bag of improvements. But, there is the rub: massively plagued by inefficiencies, at every level, plus panicking, France did not prioritize the MS-410 program. Considerable amounts of time, money and energy were wasted chasing dead ends.

Bottom line: France was unable to do this in time. https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morane-Saulnier_MS.406#Le_D-3801

Conversely, one wonders if instead starting D520 preproduction/production with the 12Y-31 could have made its bugfixing any faster/earlier than IRL.

Of course, the LN 161 would have made both questions irrelevant.

I remember reading on the Sam40 blog that the end of MS-406 production in 1940 was a little premature considering the lack of modern planes and the delays in D520 deliveries, and the fact it would incentivize the MS-410 program.

Oh gosh, I wasn't aware of this. Geez, another nail into 1940 France's coffin...

The MS-406 is a good plane. Potentially better than the Hurricane.

Hurricane was actually better. MS 406 lacked perhaps 150-200 HP to better the Hurricane I.

The problem is different. At the time of its appearance, it was clearly superior to modern versions of the Bf-109. But when the Moran went into battle, it was the same, and the Messerschmidt was already on its fifth major and two more minor modifications. If it had gone at least half of this way, it would have been a first-class fighter. Also with an engine.

Bf 109 was on it's perhaps 1st major modification - namely the engine upgrade - and that made all the difference it needed.

The Hispano-Suiza was accelerated to 1700 hp. if I am not mistaken. Up to 1100 by the end of the campaign in France. The trouble is that France mobilized late, and the Hispano-Suiza 12 was a civilian engine with a civilian approach to resource and reliability. Therefore, it gave 860 hp. And during the war, sometimes for the sake of an increase of 50 forces they agreed to an engine with a resource of 25 hours. Even in the underdeveloped USSR, with minor modifications, it was brought to 1290 hp take-off power and significantly modified to 1600 hp.

Disagreed completely.

HS 12 engine that went to 1300 HP, and post-war to 1600 HP was a completely new engine, called the HS 12Z. New stuff on it: block, head, valve train, intakes, reduction gear, pistons, connecting rods, supercharger. Same as the Griffon - it was a whole new engine, not a version of Buzzard. Same as with VK-107 - a whole new engine, not yet another version of HS 12, or even a version of M-105.

HS 12Y was military engine through and through.

The latest and best 12Y version, the -51, was good for 1000 HP, after the Merlin III was cleared for 1300 HP.

Soviets modified the M-100 (licence-built HS 12Y) into the M-103, and then into the M-105, adding the 3-valve head to the engine, a 2-speed and improved S/C, reduced the bore so the block has more material left for greater strength; engine that was good for 1290 HP (VK-105PF2) ended up being 40% heavier than the M-100.

By the way, both the Yak-1/9 and the LaGG-3/La-5 were born from the program to launch the Soviet analogue of the Codron С-714 into production.

By the time of La-5, the C-714 was dead and buried as far as military aircraft go. So was the Yak-9.

Source that Yak-1 and LaGG-3 were born from the program to launch the Soviet analogue to the C-714?

Yep, the big breakthrough for the 109 happened between the 109D and 109E, when the Jumo was swapped for the DB. The 109E first apeared during the Phony war, mid-September 1939. French fighters could reasonably face 109B and 109D (essentially the Curtis H75), but 109E was a massive leap in performance that left France behind, except perhaps the D-520 which still lacked power and came too late, not enough of them on May 10, 1940.

The DB-601 was 1100 hp

Merlin I, 1030 hp

12Y : 860 to 910 hp.

The Turbomeca Planiol compressor was to get it past 1000 hp but by this point and unlike all the other V12s (Allison, DB, Merlin) the 12Y would be at the end of its development rope. 12Z was to start at 1200 hp but was very late by 1940...

The DB-601 was 1100 hp

Merlin I, 1030 hp

12Y : 860 to 910 hp.

The Turbomeca Planiol compressor was to get it past 1000 hp but by this point and unlike all the other V12s (Allison, DB, Merlin) the 12Y would be at the end of its development rope. 12Z was to start at 1200 hp but was very late by 1940...

The 1st Emils were delivered as early as late 1938 (109E-1 in 15 copies, 109E-3 in 153 copies, in both cases before 1939).Yep, the big breakthrough for the 109 happened between the 109D and 109E, when the Jumo was swapped for the DB. The 109E first apeared during the Phony war, mid-September 1939. French fighters could reasonably face 109B and 109D (essentially the Curtis H75), but 109E was a massive leap in performance that left France behind, except perhaps the D-520 which still lacked power and came too late, not enough of them on May 10, 1940.

By late 1939, Merlin III was approved by RAF for +12 psi boost, that resulted in 1300 HP at ~9000 ft. A number of interesting articles can be found here.The DB-601 was 1100 hp

Merlin I, 1030 hp

12Y : 860 to 910 hp.

The Turbomeca Planiol compressor was to get it past 1000 hp but by this point and unlike all the other V12s (Allison, DB, Merlin) the 12Y would be at the end of its development rope. 12Z was to start at 1200 hp but was very late by 1940...

I'll start with the last question. When the USSR tested the Codron S 714, and its Yakovlev analogue, they came to the conclusion that it had no power reserve, neither for vertical nor for horizontal maneuver. Such an iron. Therefore, they decided to develop it with a more powerful engine within the framework of the concept of a wooden light fighter. The M-106, or M-105 high-altitude with two turbochargers, was planned. Thus were born the Yak-1/7, which later evolved into the Yak-9/3 and the LaGG-1/3, which evolved into the La-5/7. Only the M-106 could not be brought to fruition and the M-105 became the main one, of course without turbochargers. The chassis layout and the layout of the instruments in the cockpit were from the Codron, everything that remained except the wood..

By the time of La-5, the C-714 was dead and buried as far as military aircraft go. So was the Yak-9.

Source that Yak-1 and LaGG-3 were born from the program to launch the Soviet analogue to the C-714?

Link? Well, as a fighter of the Ukrainian army, I will not give effort to Katsap resources. If you have anything, please refer to me. Bівеr550.

Last edited:

I completely agree with you. There is only a small remark. No one has bothered to improve the 12Y since 1935. And it was a military engine, but a military engine of peacetime, where the main thing is resource and reliability. The Finns noted that by adjusting they brought their 12Y to 930 horsepower. But with a decrease in resource. The M-100, a complete copy of the 12Y, had 1000 hours of resource, the forced M-103 had 500 hours. The M-105 already had 250 hours, and the M-105PF-2 only 100 hours of resource, and this was enough for the war. Also, no one bothered to work out the 12Z, but why? There is a reliable successful engine, they buy it, planes fly, other countries also buy it, what are the problems?Yep, the big breakthrough for the 109 happened between the 109D and 109E, when the Jumo was swapped for the DB. The 109E first apeared during the Phony war, mid-September 1939. French fighters could reasonably face 109B and 109D (essentially the Curtis H75), but 109E was a massive leap in performance that left France behind, except perhaps the D-520 which still lacked power and came too late, not enough of them on May 10, 1940.

The DB-601 was 1100 hp

Merlin I, 1030 hp

12Y : 860 to 910 hp.

The Turbomeca Planiol compressor was to get it past 1000 hp but by this point and unlike all the other V12s (Allison, DB, Merlin) the 12Y would be at the end of its development rope. 12Z was to start at 1200 hp but was very late by 1940...

The same peaceful thinking, France woke up too late and realized that the war is already here.

Well, a little more about Merlin, sorry, but Merlin with 87 octane gasoline developed around 900 hp. In general, quite in the range of 12Y.

A DB-601 is a fairly large unit, also quite unreliable and insanely complex to manufacture. But of course when it worked normally it gave bonuses to the rather problematic BF-109 in battle against contemporaries.

The best fighter in the world in 1937 was French. The airplane, named Morane-Saulnier M.S.405, was a single-engine, single-seat, low wing monoplane with retractable undercarriage and closed cockpit.

The production model M.S.406 C.1 of 1939 was armed with a 20 mm gun (a secret weapon at that time) firing through the propeller hub, capable of shooting any German bombers in service. It also possessed enough speed and manoeuvrability to face the Bf 109 B, C and D of the Luftwaffe using its MAC machine guns.

During the Phoney War (3 September 1939 to 10 May 1940) the M.S.406 made 10,119 combat missions destroying 81 German airplanes. The appearance of the Bf 109 E over the French skies on 21 September 1939, amounted to a technological advantage that gave the aerial superiority to Germans at the critical moment of the Blitzkrieg offensive in May 1940.

The French answer was an improved version of the M.S.406, the M.S.410, that was externally different from the M.S.406 by having four guns in the wings, a fixed cooler, increased armour, a more inclined windshield (to house the GH 38 gunsight), Ratier 1607 electric propeller and Bronzavia propulsive exhaust pipes. It did not arrive on time though and only five 406s were transformed before the defeat.

In 1935 the firm Morane-Saulnier decided to develop a two-seat trainer to facilitate the transition of the pilots from the Dewoitine D.510 to the M.S.405 with retractable landing gear. The first prototype, called M.S.430-01, flew at 360 kph in March 1937, powered by a 390 hp. Salmson 9Ag radial engine. In June 1939 l’Armée de l'Air ordered the production of 60 units under the name M.S.435 P2 (Perfectionnement biplace), powered by a 550 hp Gnôme-Rhône GR 9 Kdrs radial engine, but the acceleration of the production of the M.S.406 and M.S.410 fighters and the acquisition of the North American 57 and 64 trainers in the USA led to the cancellation of the M.S.435.

Foreseeing the possibility of a serious delay in the production of the Hispano-Suiza H.S.12 Y-31 engine, the firm considered the construction of M.S.408 C.1 single-seat light fighter, powered by a radial engine GR 9 Kdrs or a Hispano-Suiza 14 Aa-10 armed with only wing mounted MAC 34A machine guns. The prototype M.S.408-01, with 10.71 m wingspan, was built using many parts of the M.S.430 and a Salmson 9 Ag engine, but the increasing availability of the 12Y-31 dismissed its serial production.

On 15 June 1936 l'Armée de l'Air high command published the Chasseur Monoplace C.1 specification, calling for a single-seat fighter capable of flying at 500 kph at an altitude of 4,000 m, reaching 8,000 m. ceiling in less than 15 minutes. Intended to replace the Morane-Saulnier M.S.406, the new fighter should be powered by a 935 hp Hispano-Suiza H.S. 12Y-45, 12-cylinder ‘Vee’ liquid-cooled engine and armed with one cannon and two machine guns.

Upon learning of the performances of the Messerschmitt Bf 109 B-1, that the Germans had started to manufacture in the fall of 1936, the C.1 specification was amended as Program Technique A23 (12 January 1937) calling for 520 kph maximum speed and armament increase to one 20 mm Hispano-Suiza H.S.404 cannon and four 7.5 mm MAC 34 M39 belt-feed machine guns. Four prototypes were produced to fulfil the requirement: The Morane-Saulnier M.S.450, the S.N.A.C.A.O. 200, the Arsenal VG 33 and the Dewoitine D.520.

By January 1938, French intelligence services estimated the Luftwaffe strength at 2,850 modern aircraft, including 850 fighters. In response the Ministère de l'Air issued the Plan V (15 March 1938) to increase the inventory of the Armée de l'Air to 2,617 aircraft, including 1,081 fighters, to equip 32 Groupes de Chasse and 16 Escadrilles Régionales. But on 1 April 1939 l'Armée de l'Air had only 104 M.S.405/406, one Bloch M.B.151 and 42 Curtiss H.75A and none of these fighters reached the 500 kph.

The M.S.450 prototype was an aerodynamically improved version of the M.S.406. It could fly at 560 kph propelled by an 1,100 hp H.S.12 Y-51 engine, but the Ministère de l'Air did not want to interrupt the manufacturing of the M.S.410 and dismissed its production.

The C.A.O. 200 reached the 550 kph with the same engine than the M.S. 406, but its production was also dismissed due to a longitudinal instability revealed during test flights in August 1939. During the Battle of France the prototype participated in the Villacoublay defence, armed with a H.S. 404, managing to shoot down a Heinkel He 111 on 15 June 1940.

The Arsenal VG 30 was designed as a light fighter to fulfil the Chasseur Monoplace C.1 (3 June 1937) specification that called for a small fighter propelled by one 690 hp Hispano-Suiza H.S.12 X crs engine and armed with one 20 mm H.S.9 cannon and two 7.5 mm MAC 34A drum-feed machine guns, from the obsolete Dewoitine D.510 fighters. Anticipating the possibility of a long attrition war, the VG 30 was built in wood/plywood, not to compete with the conventional fighters in the use of strategic materials. It could be manufactured in the third part of the time than an M.S. 406 for 630,000 F, a 75 per cent of the price of a Bloch M.B.152.

On October 1938, the VG 30-01 prototype reached a maximum speed that was 30 kph higher than that of the M.S.406, propelled by a less powerful 180 hp engine. It was estimated that it could fly at 560 kph with the engine of the M.S.406 and the VG 33 prototype, armed with one H.S. 404 and four MAC 34 M39, was built with that purpose.

Fifteen days after the declaration of war on Germany the S.N.C.A. du Nord received a commission for the manufacture of 220 units of the VG 33, later expanded to 500. Deliveries to l’Armée de l’Air should start at the beginning of 1940. But there were problems with the import of spruce from Canada and Romania and only seven planes entered combat between 18 and 25 June 1940, carrying out 36 missions with the GC I/55. The VG 33 outperformed the Bf 109 E-1 in manoeuvrability and fire power and was almost as fast with a less powerful 240 hp engine.

On 20 January 1940, the VG 34-01 prototype reached 590 kph, powered by one H.S.12 Y-45.

In February the VG 35-01 flew powered by a 1,100 hp H.S.12 Y-51 engine and the decision was taken to start the production of the VG 32, propelled by the American engine Allison V-1710 C-15, but only a prototype was eventually built before the German attack. In May, the VG 36-01 flew with a 1,100 hp H.S.12 Y-51. The VG 39-01 flew during the same month, propelled by a 1,200 hp H.S.12 Z reaching the 625 kph.

The first aircraft to fulfil the specifications of the Programme Technique A23 was the prototype Dewoitine D.520-01, exceeding the 520 kph speed on December 1938 and being declared winner of the contest. In June 1939 the Ministère de l'Air made an order of 600 planes, later expanded to 710, that were to be delivered to the l'Armée de l'Air from the beginning of January 1940. Unfortunately for the French the deliveries were delayed by problems with the engine cooling, the freezing of the MAC 34 M 39 machine guns and the pneumatic firing system.

The day of the German attack (10 May 1940) only two-hundred-and-twenty-eight D.520 had been manufactured, 75 out of which had been accepted by the Centre de Réception des Avions de Série (CRAS) and 50 were making their operational conversion into the GC I/3. When the armistice came (25 June 1940) four-hundred-and-thirty-seven D.520 had been manufactured, of which 112 were in the CRAS for armament installation and 105 had been destroyed by different causes, 53 of them in combat.

The D.520 was the only French fighter that faced the Bf 109 E-3 in conditions of equality. That, despite the scant experience of its pilots with the new model and the accidents caused by the HE 20x110 ammunition of the H.S.404 cannon, causing premature explosions within the barrel when firing the second burst. Tests carried out with a Bf 109 captured at the end of 1939 revealed that the D.520 matched its climb rate between 4,000 and 6,000 m (with 190 hp less power) beating the German aircraft in diving, structural strength, manoeuvrability and fire power.

To avoid competing against Morane-Saulnier for the Hispano-Suiza engines, the Marcel Bloch firm chose the Gnome-Rhône Série 14 radial engines to propel its fighters between 1937 and 1942. Its first design, the Bloch M.B.150, was a loser in the Chasseur Monoplace C.1 contest of 1934. However, the publication of Plan V (15 March 1938) allowed the firm to obtain a contract for the manufacture of 140 units of the improved M.B.151 model, powered by a 920 hp Gnôme-Rhône 14N-35.

During the Spanish Civil War, the radial engine fighters proved that they needed a 30 per cent of extra power to fight on equal terms with the in-line engine fighters. The M.B. 151 had 180 hp less than the Messerschmitt Bf 109 E, was 105 kph slower due to the poor aerodynamic design of the engine cowling and was only armed with four 7.5 mm MAC 34A drum-feed machine guns, with 300 rounds each.

On July 1939, after some tests carried out in the Centre d’Expériences at Rheims, the M.B.151 was considered unsuited for first-line duties. l’Armée de l’Air and l’Aéronavale (French naval aviation) mainly used it as advanced trainer at the Centres d’Instruction de Chasse. It was eventually used in combat, four were destroyed and one of them rammed a Fiat C.R.42 of the Regia Aeronautica.

They tried to correct all these deficiencies with the M.B.152, using a 1,100 hp fourteen-cylinder air-cooled Gnôme-Rhône 14N-49, with a new 85 cm diameter cowling, inspired by that of the Curtiss H.75A, driving a variable-pitch Chauvière 371 propeller. Its armament consisted of two H.S.404 cannon and two MAC 34A machine guns installed on the wings. The gunsight reflector was a Baille-Lemaire GH 38.

The new fighter was 88 kph slower than the Bf 109 E-1 in level flight and 50 kph slower in dive but surpassed the German aircraft in firepower and structural strength. Forced to prematurely entering service, the M.B.152 suffered several accidents. The engine caught fire in inverted flight due to of a bad design of the carburettor. The deficient pneumatically-actuated firing system operated the weapons with delay and did not have enough pressure to operate the cannons at an altitude above 7,000 m.

After the German-Soviet non-aggression Pact (23 August 1939) the French communists received order of delaying the weapons production through a program of strikes and coordinated sabotages. The most affected were the Farman and Renault factories that manufactured the only bomber capable of reaching Berlin and the tanks that could surpass those of the Germans. But the biggest damage was the chaos created in the manufacture and distribution of aircraft components.

When the Allies declared war on Germany (3 September 1939) out of the hundred-and-twenty-three Bloch fighters that have been built, ninety-five did not have propellers and half of them had not yet received weapons, radio equipment or gunsights. At the beginning of 1940, delays in the delivery of the Messier landing gear forced the manufacture suspension of fifty-nine M.B.152 fighters. Fearing that the machine guns would fall into the hands of communists, l'Armée de l'Air was in charge of the installation, but the process was slow and required numerous modifications.

The M.B.152 came from factory temporarily equipped with wooden propellers, 14N-25 engines with the old cowling of 100 cm diameter and OPL R-39 gunsights. Faced with a shortage of Chauvière 371 propellers, many were sent to combat with Gnôme-Rhône 2590 propellers (with adjustable pitch in ground only) or armed only with machine guns, due to the delays in the delivery of the H.S.404 cannons.

The replacement of the waste pneumatic firing system by Deltour-Jay electro-pneumatic devices which ensured a more rapid trigger response, caused further delays at the beginning of 1940. On 10 March 1940 there still were fifty Bloch M.B.152 fighters without armament and propellers in the Entrepôt 301 centre. When the German attack came thirty days later, hundred-and-forty M.B.151, three-hundred-and-sixty-three M.B.152, four M.B.155 and one M.B.153, with Twin Wasp engine, had been accepted by l’Armée de l’Air, but only eighty-three of them, considered bons de guerre (combat-ready), had been delivered to the Groupes de Chasse. During the Battle of France, the Bloch fighters shot downed 146 German aircraft, including forty-five Bf 109 fighters. Eighty M.B.152 and four M.B.151 were destroyed for different causes.

Worse still was the availability of the bombers, whose priority was lower than that of the fighters. The delivery of the Amiot 350, Bloch M.B.174 and Breguet 693 bons de guerre to the Groupes de Bombardement suffered from inadequate supplies of the Alkan and Gardy bomb racks and many LeO 45 did not receive the Gnôme-Rhône 2590 propellers in time, being destroyed in land without any opportunity to combat.

Consequence of the disorganization caused by the sabotages, on Armistice Day (25 June 1940) l’Armée de l’Air had 2,348 planes, many more than on the invasion day, even counting losses. Most fell intact in the hands of the Germans.

On 10 May 1940 l’Armée de l’Air had five Escadrilles de Chasse de Nuit with forty-seven Potez 631 night fighters. These aircraft were operating in sectors of the front that were 15 km wide and 20 km deep, helped by searchlights and sound locators, with one control centre positioning the airplanes by using direction finding (D/F) equipment. Depending on conditions of visibility, a night fighter pilot could see an unilluminated bomber from between 400 and 600 m, and between 1,000 and 6,000 when illuminated by searchlights. During the Battle of France, the Potez 63 managed to shoot down three Heinkel He 111 and one Dornier Do 17.

The failure of the M.B.151 and the delays in the delivery of the M.B.152 forced l’Armée de l’Air to maintain various types of obsolete fighters in service. The Dewoitine D.510, that constituted 70 per cent of the French fighter force during the Munich Agreement, still equipped five Groupes de Chasse and two Escadrilles of the Aéronavale (141 aircraft) at the time of the Poland invasion. At the beginning of 1940 two Patrouilles de Défense were still active with 40 aircraft piloted by Poles.

On September 1939 one Escadrille of the Armée de l’Air equipped with Dewoitine D.371 fighters were based in Bizerte-Tunis and the Aéronavale still used thirteen D.373 and D.376 aircraft. When the war started, three Groupes de Chasse, still equipped with Loire 46 fighters, were making the transition to the M.S. 406. By May 1940 twenty-three aircraft were left in various training schools and sixteen in reserve.

Some old biplanes of the Blériot-SPAD 510 type were got back into service in the Grupe Aérien Régional de Chasse at Le Havre-Octeville and in the Centre d’Instruction à la Chasse at Montpellier, being gradually replaced by the Bloch M.B.151.

The force of fighters of the Air Component of the British Expeditionary Force (B.E.F.) were integrated by two squadrons of biplane fighters Gloster Gladiator Mk.I (30 aircraft) and two squadrons of Hawker Hurricane Mk.I and lost most of their aircraft in the first week of combats. The rest were destroyed during the bombardment of the Vitry-en-Artois airfield.

The Advanced Air Striking Force also had two squadrons of Hurricane Mk.I in Belgium, later joined by seven more. During the Battle of France, seventy-five Hurricanes were destroyed in combat, another 120 had to be abandoned to the enemy, due to lack of spares, and only 66 returned to England. The RAF also lost nine Defiant Mk.I fighters on Netherlands and sixty-seven Spitfire Mk.I on Dunkirk.

The 'Panic Effect' caused by the Munich Agreement forced the French Government to carry out large massive purchases of foreign aircraft, initiating talks with the USSR for the acquisition of Polikarpov I-16 fighters, an operation that was cancelled after the German-Soviet non-aggression Pact. They placed orders for two-hundred Curtiss H.75A and hundred Curtiss H.81 (P-40) fighters to the USA and acquired forty Koolhoven FK.58 fighters to the Netherlands together with the license to manufacture them in Nevers-France. One Spitfire Mk.I was also purchased to Great Britain to study the compatibility of its engine with the D.520.

On March 1940 l’Armée de l’Air had 18 serviceable Koolhoven. During the Battle of France they were used to equip four Patrouilles de Défense piloted by Poles. On June 25 ten of them had survived the combats.

The Curtiss H.81 did not arrive in time to prevent the fall of France and they were transferred to the RAF, but the H.75A performed well, fighting on equal terms with the Messerschmitt Bf 109 D during the Phoney War and eluding the attacks of the Bf 109 E during the Battle of France, thanks to its greater manoeuvrability, but its armament of four machine guns proved to be insufficient to destroy German bombers.

During the period between both World Wars, the size and weight of the fighters was progressively augmented in parallel with the increasing power of the available engines. Against that general trend, there was a minority of aeronautical designers defending the small sized fighters, known as 'Jockey Fighters' at that time. This type of airplanes, if well designed, could generally compete in performance with the conventional fighters, using a less powerful engine, with an important save in fuel, manpower and strategic materials. They were also easier to maintain and store and their reduced size and weight helped to increase agility in combat, making more difficult to be seen by the rear gunners in the bombers, or by the pilots in the escort fighters, and their destruction required a higher consumption of ammunition.

At the beginning of World War II, the conventional fighters used to have 10 to 12 m of wingspan, operational weight of 2,500 to 3,500 kg and a maximum speed of 450 to 500 km/h. The light fighters of the time could be divided in two categories:

‘Jockey Fighters’, with less than 10 m. wingspan, maximum weight of 1,800 to 2,500 kg and the same speed than the conventional fighters.

‘Midget Fighters’, with less than 10 m wingspan, maximum weight of 600 to 1,800 kg and maximum speed of 350 to 400 km/h.

The production model M.S.406 C.1 of 1939 was armed with a 20 mm gun (a secret weapon at that time) firing through the propeller hub, capable of shooting any German bombers in service. It also possessed enough speed and manoeuvrability to face the Bf 109 B, C and D of the Luftwaffe using its MAC machine guns.

During the Phoney War (3 September 1939 to 10 May 1940) the M.S.406 made 10,119 combat missions destroying 81 German airplanes. The appearance of the Bf 109 E over the French skies on 21 September 1939, amounted to a technological advantage that gave the aerial superiority to Germans at the critical moment of the Blitzkrieg offensive in May 1940.

The French answer was an improved version of the M.S.406, the M.S.410, that was externally different from the M.S.406 by having four guns in the wings, a fixed cooler, increased armour, a more inclined windshield (to house the GH 38 gunsight), Ratier 1607 electric propeller and Bronzavia propulsive exhaust pipes. It did not arrive on time though and only five 406s were transformed before the defeat.

In 1935 the firm Morane-Saulnier decided to develop a two-seat trainer to facilitate the transition of the pilots from the Dewoitine D.510 to the M.S.405 with retractable landing gear. The first prototype, called M.S.430-01, flew at 360 kph in March 1937, powered by a 390 hp. Salmson 9Ag radial engine. In June 1939 l’Armée de l'Air ordered the production of 60 units under the name M.S.435 P2 (Perfectionnement biplace), powered by a 550 hp Gnôme-Rhône GR 9 Kdrs radial engine, but the acceleration of the production of the M.S.406 and M.S.410 fighters and the acquisition of the North American 57 and 64 trainers in the USA led to the cancellation of the M.S.435.

Foreseeing the possibility of a serious delay in the production of the Hispano-Suiza H.S.12 Y-31 engine, the firm considered the construction of M.S.408 C.1 single-seat light fighter, powered by a radial engine GR 9 Kdrs or a Hispano-Suiza 14 Aa-10 armed with only wing mounted MAC 34A machine guns. The prototype M.S.408-01, with 10.71 m wingspan, was built using many parts of the M.S.430 and a Salmson 9 Ag engine, but the increasing availability of the 12Y-31 dismissed its serial production.

On 15 June 1936 l'Armée de l'Air high command published the Chasseur Monoplace C.1 specification, calling for a single-seat fighter capable of flying at 500 kph at an altitude of 4,000 m, reaching 8,000 m. ceiling in less than 15 minutes. Intended to replace the Morane-Saulnier M.S.406, the new fighter should be powered by a 935 hp Hispano-Suiza H.S. 12Y-45, 12-cylinder ‘Vee’ liquid-cooled engine and armed with one cannon and two machine guns.

Upon learning of the performances of the Messerschmitt Bf 109 B-1, that the Germans had started to manufacture in the fall of 1936, the C.1 specification was amended as Program Technique A23 (12 January 1937) calling for 520 kph maximum speed and armament increase to one 20 mm Hispano-Suiza H.S.404 cannon and four 7.5 mm MAC 34 M39 belt-feed machine guns. Four prototypes were produced to fulfil the requirement: The Morane-Saulnier M.S.450, the S.N.A.C.A.O. 200, the Arsenal VG 33 and the Dewoitine D.520.

By January 1938, French intelligence services estimated the Luftwaffe strength at 2,850 modern aircraft, including 850 fighters. In response the Ministère de l'Air issued the Plan V (15 March 1938) to increase the inventory of the Armée de l'Air to 2,617 aircraft, including 1,081 fighters, to equip 32 Groupes de Chasse and 16 Escadrilles Régionales. But on 1 April 1939 l'Armée de l'Air had only 104 M.S.405/406, one Bloch M.B.151 and 42 Curtiss H.75A and none of these fighters reached the 500 kph.

The M.S.450 prototype was an aerodynamically improved version of the M.S.406. It could fly at 560 kph propelled by an 1,100 hp H.S.12 Y-51 engine, but the Ministère de l'Air did not want to interrupt the manufacturing of the M.S.410 and dismissed its production.

The C.A.O. 200 reached the 550 kph with the same engine than the M.S. 406, but its production was also dismissed due to a longitudinal instability revealed during test flights in August 1939. During the Battle of France the prototype participated in the Villacoublay defence, armed with a H.S. 404, managing to shoot down a Heinkel He 111 on 15 June 1940.

The Arsenal VG 30 was designed as a light fighter to fulfil the Chasseur Monoplace C.1 (3 June 1937) specification that called for a small fighter propelled by one 690 hp Hispano-Suiza H.S.12 X crs engine and armed with one 20 mm H.S.9 cannon and two 7.5 mm MAC 34A drum-feed machine guns, from the obsolete Dewoitine D.510 fighters. Anticipating the possibility of a long attrition war, the VG 30 was built in wood/plywood, not to compete with the conventional fighters in the use of strategic materials. It could be manufactured in the third part of the time than an M.S. 406 for 630,000 F, a 75 per cent of the price of a Bloch M.B.152.

On October 1938, the VG 30-01 prototype reached a maximum speed that was 30 kph higher than that of the M.S.406, propelled by a less powerful 180 hp engine. It was estimated that it could fly at 560 kph with the engine of the M.S.406 and the VG 33 prototype, armed with one H.S. 404 and four MAC 34 M39, was built with that purpose.

Fifteen days after the declaration of war on Germany the S.N.C.A. du Nord received a commission for the manufacture of 220 units of the VG 33, later expanded to 500. Deliveries to l’Armée de l’Air should start at the beginning of 1940. But there were problems with the import of spruce from Canada and Romania and only seven planes entered combat between 18 and 25 June 1940, carrying out 36 missions with the GC I/55. The VG 33 outperformed the Bf 109 E-1 in manoeuvrability and fire power and was almost as fast with a less powerful 240 hp engine.

On 20 January 1940, the VG 34-01 prototype reached 590 kph, powered by one H.S.12 Y-45.

In February the VG 35-01 flew powered by a 1,100 hp H.S.12 Y-51 engine and the decision was taken to start the production of the VG 32, propelled by the American engine Allison V-1710 C-15, but only a prototype was eventually built before the German attack. In May, the VG 36-01 flew with a 1,100 hp H.S.12 Y-51. The VG 39-01 flew during the same month, propelled by a 1,200 hp H.S.12 Z reaching the 625 kph.

The first aircraft to fulfil the specifications of the Programme Technique A23 was the prototype Dewoitine D.520-01, exceeding the 520 kph speed on December 1938 and being declared winner of the contest. In June 1939 the Ministère de l'Air made an order of 600 planes, later expanded to 710, that were to be delivered to the l'Armée de l'Air from the beginning of January 1940. Unfortunately for the French the deliveries were delayed by problems with the engine cooling, the freezing of the MAC 34 M 39 machine guns and the pneumatic firing system.

The day of the German attack (10 May 1940) only two-hundred-and-twenty-eight D.520 had been manufactured, 75 out of which had been accepted by the Centre de Réception des Avions de Série (CRAS) and 50 were making their operational conversion into the GC I/3. When the armistice came (25 June 1940) four-hundred-and-thirty-seven D.520 had been manufactured, of which 112 were in the CRAS for armament installation and 105 had been destroyed by different causes, 53 of them in combat.

The D.520 was the only French fighter that faced the Bf 109 E-3 in conditions of equality. That, despite the scant experience of its pilots with the new model and the accidents caused by the HE 20x110 ammunition of the H.S.404 cannon, causing premature explosions within the barrel when firing the second burst. Tests carried out with a Bf 109 captured at the end of 1939 revealed that the D.520 matched its climb rate between 4,000 and 6,000 m (with 190 hp less power) beating the German aircraft in diving, structural strength, manoeuvrability and fire power.

To avoid competing against Morane-Saulnier for the Hispano-Suiza engines, the Marcel Bloch firm chose the Gnome-Rhône Série 14 radial engines to propel its fighters between 1937 and 1942. Its first design, the Bloch M.B.150, was a loser in the Chasseur Monoplace C.1 contest of 1934. However, the publication of Plan V (15 March 1938) allowed the firm to obtain a contract for the manufacture of 140 units of the improved M.B.151 model, powered by a 920 hp Gnôme-Rhône 14N-35.

During the Spanish Civil War, the radial engine fighters proved that they needed a 30 per cent of extra power to fight on equal terms with the in-line engine fighters. The M.B. 151 had 180 hp less than the Messerschmitt Bf 109 E, was 105 kph slower due to the poor aerodynamic design of the engine cowling and was only armed with four 7.5 mm MAC 34A drum-feed machine guns, with 300 rounds each.

On July 1939, after some tests carried out in the Centre d’Expériences at Rheims, the M.B.151 was considered unsuited for first-line duties. l’Armée de l’Air and l’Aéronavale (French naval aviation) mainly used it as advanced trainer at the Centres d’Instruction de Chasse. It was eventually used in combat, four were destroyed and one of them rammed a Fiat C.R.42 of the Regia Aeronautica.

They tried to correct all these deficiencies with the M.B.152, using a 1,100 hp fourteen-cylinder air-cooled Gnôme-Rhône 14N-49, with a new 85 cm diameter cowling, inspired by that of the Curtiss H.75A, driving a variable-pitch Chauvière 371 propeller. Its armament consisted of two H.S.404 cannon and two MAC 34A machine guns installed on the wings. The gunsight reflector was a Baille-Lemaire GH 38.

The new fighter was 88 kph slower than the Bf 109 E-1 in level flight and 50 kph slower in dive but surpassed the German aircraft in firepower and structural strength. Forced to prematurely entering service, the M.B.152 suffered several accidents. The engine caught fire in inverted flight due to of a bad design of the carburettor. The deficient pneumatically-actuated firing system operated the weapons with delay and did not have enough pressure to operate the cannons at an altitude above 7,000 m.

After the German-Soviet non-aggression Pact (23 August 1939) the French communists received order of delaying the weapons production through a program of strikes and coordinated sabotages. The most affected were the Farman and Renault factories that manufactured the only bomber capable of reaching Berlin and the tanks that could surpass those of the Germans. But the biggest damage was the chaos created in the manufacture and distribution of aircraft components.

When the Allies declared war on Germany (3 September 1939) out of the hundred-and-twenty-three Bloch fighters that have been built, ninety-five did not have propellers and half of them had not yet received weapons, radio equipment or gunsights. At the beginning of 1940, delays in the delivery of the Messier landing gear forced the manufacture suspension of fifty-nine M.B.152 fighters. Fearing that the machine guns would fall into the hands of communists, l'Armée de l'Air was in charge of the installation, but the process was slow and required numerous modifications.

The M.B.152 came from factory temporarily equipped with wooden propellers, 14N-25 engines with the old cowling of 100 cm diameter and OPL R-39 gunsights. Faced with a shortage of Chauvière 371 propellers, many were sent to combat with Gnôme-Rhône 2590 propellers (with adjustable pitch in ground only) or armed only with machine guns, due to the delays in the delivery of the H.S.404 cannons.

The replacement of the waste pneumatic firing system by Deltour-Jay electro-pneumatic devices which ensured a more rapid trigger response, caused further delays at the beginning of 1940. On 10 March 1940 there still were fifty Bloch M.B.152 fighters without armament and propellers in the Entrepôt 301 centre. When the German attack came thirty days later, hundred-and-forty M.B.151, three-hundred-and-sixty-three M.B.152, four M.B.155 and one M.B.153, with Twin Wasp engine, had been accepted by l’Armée de l’Air, but only eighty-three of them, considered bons de guerre (combat-ready), had been delivered to the Groupes de Chasse. During the Battle of France, the Bloch fighters shot downed 146 German aircraft, including forty-five Bf 109 fighters. Eighty M.B.152 and four M.B.151 were destroyed for different causes.

Worse still was the availability of the bombers, whose priority was lower than that of the fighters. The delivery of the Amiot 350, Bloch M.B.174 and Breguet 693 bons de guerre to the Groupes de Bombardement suffered from inadequate supplies of the Alkan and Gardy bomb racks and many LeO 45 did not receive the Gnôme-Rhône 2590 propellers in time, being destroyed in land without any opportunity to combat.

Consequence of the disorganization caused by the sabotages, on Armistice Day (25 June 1940) l’Armée de l’Air had 2,348 planes, many more than on the invasion day, even counting losses. Most fell intact in the hands of the Germans.

On 10 May 1940 l’Armée de l’Air had five Escadrilles de Chasse de Nuit with forty-seven Potez 631 night fighters. These aircraft were operating in sectors of the front that were 15 km wide and 20 km deep, helped by searchlights and sound locators, with one control centre positioning the airplanes by using direction finding (D/F) equipment. Depending on conditions of visibility, a night fighter pilot could see an unilluminated bomber from between 400 and 600 m, and between 1,000 and 6,000 when illuminated by searchlights. During the Battle of France, the Potez 63 managed to shoot down three Heinkel He 111 and one Dornier Do 17.

The failure of the M.B.151 and the delays in the delivery of the M.B.152 forced l’Armée de l’Air to maintain various types of obsolete fighters in service. The Dewoitine D.510, that constituted 70 per cent of the French fighter force during the Munich Agreement, still equipped five Groupes de Chasse and two Escadrilles of the Aéronavale (141 aircraft) at the time of the Poland invasion. At the beginning of 1940 two Patrouilles de Défense were still active with 40 aircraft piloted by Poles.

On September 1939 one Escadrille of the Armée de l’Air equipped with Dewoitine D.371 fighters were based in Bizerte-Tunis and the Aéronavale still used thirteen D.373 and D.376 aircraft. When the war started, three Groupes de Chasse, still equipped with Loire 46 fighters, were making the transition to the M.S. 406. By May 1940 twenty-three aircraft were left in various training schools and sixteen in reserve.

Some old biplanes of the Blériot-SPAD 510 type were got back into service in the Grupe Aérien Régional de Chasse at Le Havre-Octeville and in the Centre d’Instruction à la Chasse at Montpellier, being gradually replaced by the Bloch M.B.151.

The force of fighters of the Air Component of the British Expeditionary Force (B.E.F.) were integrated by two squadrons of biplane fighters Gloster Gladiator Mk.I (30 aircraft) and two squadrons of Hawker Hurricane Mk.I and lost most of their aircraft in the first week of combats. The rest were destroyed during the bombardment of the Vitry-en-Artois airfield.

The Advanced Air Striking Force also had two squadrons of Hurricane Mk.I in Belgium, later joined by seven more. During the Battle of France, seventy-five Hurricanes were destroyed in combat, another 120 had to be abandoned to the enemy, due to lack of spares, and only 66 returned to England. The RAF also lost nine Defiant Mk.I fighters on Netherlands and sixty-seven Spitfire Mk.I on Dunkirk.

The 'Panic Effect' caused by the Munich Agreement forced the French Government to carry out large massive purchases of foreign aircraft, initiating talks with the USSR for the acquisition of Polikarpov I-16 fighters, an operation that was cancelled after the German-Soviet non-aggression Pact. They placed orders for two-hundred Curtiss H.75A and hundred Curtiss H.81 (P-40) fighters to the USA and acquired forty Koolhoven FK.58 fighters to the Netherlands together with the license to manufacture them in Nevers-France. One Spitfire Mk.I was also purchased to Great Britain to study the compatibility of its engine with the D.520.