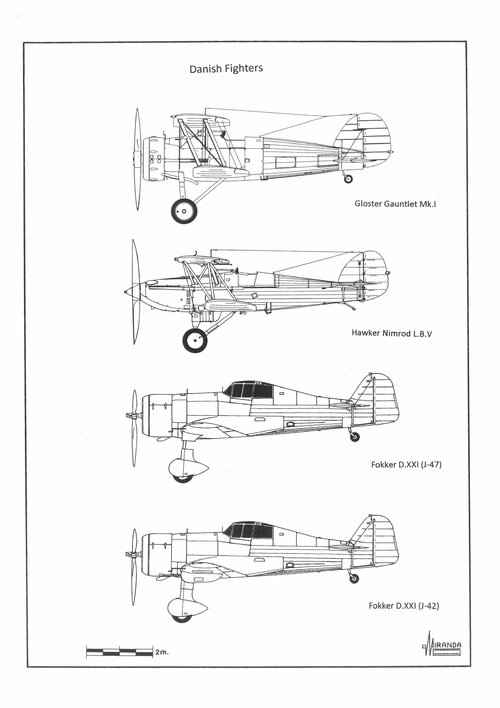

The plan Operation Weserübung Süd, included the capture on April 9,1940 of the Danish Aalborg airfield in northern Jutland, for refuelling the Messerschmitt Bf 110 fighters. At that time the Danish Naval Flying Service did not have a single modern aircraft to its disposition and had only nine Hawker Nimrod L.B.V. biplane fighters at the Avnø Naval Air Station.

On the invasion day the entire four squadron-strong of the Danish Army Air Service consisted of 45 aircraft based in Copenhagen-Værløse airfield: thirteen Gloster Gauntlet II J biplane fighters, eight Fokker D.XXI monoplane fighters, twenty-two Fokker CV reconnaissance/light bomber biplanes, one de Havilland Dragonfly transport and one Cierva C.30 autogyro.

The Bf 110 heavy fighters of the ZG.1 and ZG.76 carried out a mission of strafing over Værløse destroying three D.XXI and one Gauntlet and damaging three D.XXI and several Gauntlets.

The Oberkommando der Luftwaffe (OKL) had overestimated the danger of the D.XXI because of the publicity given to the experimental installation of two 23 mm Madsen cannons on the J-42 plane in May 1939. The Madsen 23x106 had a rate of fire superior to the 20 mm Ikaria MG-FF cannon used by the Bf 110 and to the Hispano-Suiza H.S. 404 cannon used by the Morane MS 406, but its powerful recoil was considered excessive to install it on the wings of a single engine fighter.

The Danish D.XXI were armed with just two 7.9 mm Madsen machine guns that fired, synchronized with the propeller, through blast tubes located between the lower cylinders of the engine, in four and eight o'clock positions.

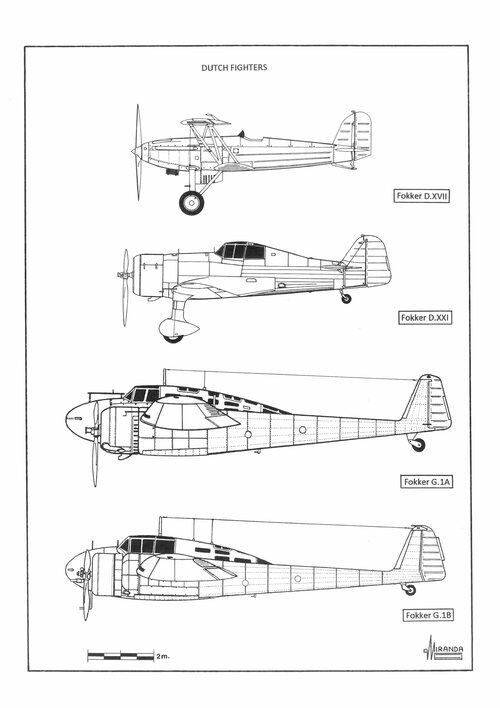

In the mid-1930s, a design team from Fokker, under the direction of Erich Schatzki, concluded that it would not be effective to build a monoplane fighter with retractable undercarriage using the 600-700 hp engines available at that time.

Calculations indicated that disadvantages in increased weight and mechanical problems would not justify the three per cent increase in overall speed that would have been obtained by hiding the landing gear in the wings. In 1935 Fokker took the decision to build the D.XXI fighter, with fixed undercarriage streamlined to the greatest possible. During flight tests carried out in February 1936 with the FD-322 prototype, it was proven that the drag generated by the landing gear was only 10 per cent of the drag generated by the entire airframe.

The failure of the British prototypes, with which the firms Vickers, Folland and Bristol tried to comply with the terms of the F5/34 specification, and the success of the Nakajima Ki.27 fighters in Khalkin Gol, confirmed Fokker's calculations. The Dutch Government did not expect a war with Germany and chose to manufacture the D.XXI - designed to be exported to countries with limited resources - instead of a more advanced fighter for national defence: the projected Fokker D.XXI H (23 May 1936) would have been powered by a 910 hp Hispano-Suiza H.S. 12Y-45 ‘Vee’ engine with retractable landing gear, one 20mm H.S.9 cannon firing through the propeller hub and four wing mounted 7.9mm FN/Browning M-36 machine guns.

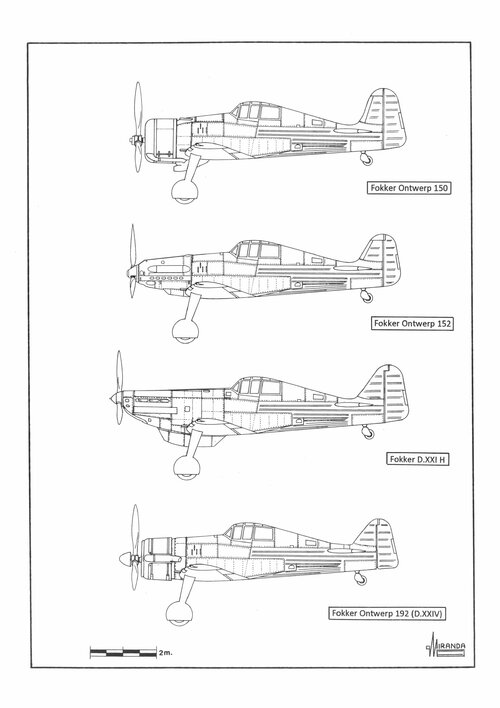

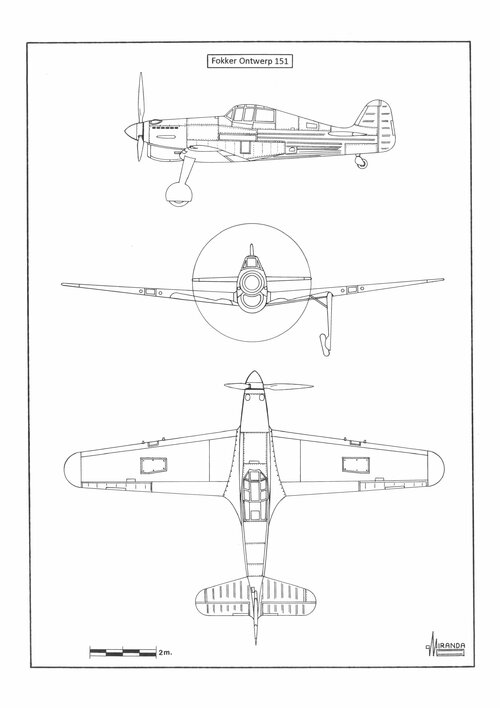

The Fokker D.XXII fighter project was considered at the end of 1937, either with a 1,050 hp Rolls-Royce Merlin II (Ontwerp 151- 12 January 1938) or with a 1,375 hp Bristol Hercules radial engine (Ontwerp 150- 27 September 1939). The Ontwerp 152 was a variant powered by a 1,090 hp German Daimler-Benz DB 600 H engine designed for the Swiss Government.

The D.XXII would be equipped with retractable undercarriage like that of the Ontwerp 150 and armed with four M-36 machine guns in the wings and two more on the nose. These machine guns were moved to the sides of the fuselage in the Ontwerp 151. The Ontwerp 152 would have a 7.9 mm MG 17 firing through the propeller hub and four more in the wings.

Again, calculations showed that the Ontwerp 151 would have been faster than the Hawker Hurricane Mk. I and a suitable opponent for the Messerschmitt Bf 109 E. On 19 June 1939, Fokker proposed the D. XXIV version. It basically was a D.XXI with retractable undercarriage and a 1,060 hp Bristol Taurus or a 905 hp Bristol Perseus radial engines.

During the night of 9 to 10 May 1940 the Germans began their Operation Fall Gelb -assault to the West- that would not stop until Dunkirk. During the invasion of the Netherlands the Luftwaffe used hundred-and-eighty Messerschmitt Bf 109 E, sixty-two Bf 110 C, hundred-and-ninety-six Heinkel He 111 P, thirty-four Junkers Ju 88, twenty-eight Ju 87, eighteen Henschel Hs 126, nine Henschel Hs 123, twenty-eight Heinkel He 115, twelve Heinkel He 59, fifteen Dornier Do 17 P and four-hundred-and-thirty Ju 52/3m.

The Dutch Air Force (Luchtvaartafdeling) had twenty-eight single engine fighters Fokker D.XXI based at Schiphol, de Kooy and Ypenburg, twenty-three heavy fighters Fokker G.1A based in Bergen and six G.1B based in Waalhaven (the latter were unarmed and they were used for training), six obsolete Fokker D.XVII biplane fighters, nine Fokker T.V medium bombers, eleven Douglas 8A-3N attack bombers, fifteen Fokker C.X light bombers, sixty-one Fokker C.V reconnaissance airplanes and sixteen Koolhoven FK.51 trainers.

The climb rate of the D.XXI was insufficient to intercept the Do 17 P reconnaissance airplanes flying at 7,000-9,000 m and lacked the firepower to shoot down the He 111 in a single attack. It could dodge the Bf 109, thanks to their greater manoeuvrability, but it was not fast enough to reach the Bf 110. Eleven aircraft were shot down in dog fight in just five days, five strafed, eight destroyed by the Dutch themselves to prevent their capture, and four were captured. In return they managed to shoot down 16 German planes.

The Fokker G.1A was between 40 and 70 km/h slower than the Bf 109 and Bf 110 and it was less manoeuvrable because of its excessive weight. Its powerful armament of eight FN/Browning M-36 could easily destroy any German bomber but the G.1A often carried only 100 rounds of 7.9 mm ammunition for each machine gun to prevent crashes caused by the weight in the nose. The first Luftwaffe attack managed to destroy eleven planes, taken by surprise on the ground, five more were shot down in combat and two in accidents in the four following days.

On 13 May, three G.1Bs were hastily armed with four M-36 and joined the combat. The G.1s shot downed four He 111, six Ju 52, one Bf 110, one Bf 109, one Ju 87 and one Do 215. In total, the Luftwaffe lost two-hundred-and-twenty Ju 52/3m, twenty-eight He 111, eighteen Ju 88, six Ju 87, eight Bf 110, twenty-nine Bf 109, six Hs 126 and two Hs 123. They destroyed ninety-four Dutch aircraft.

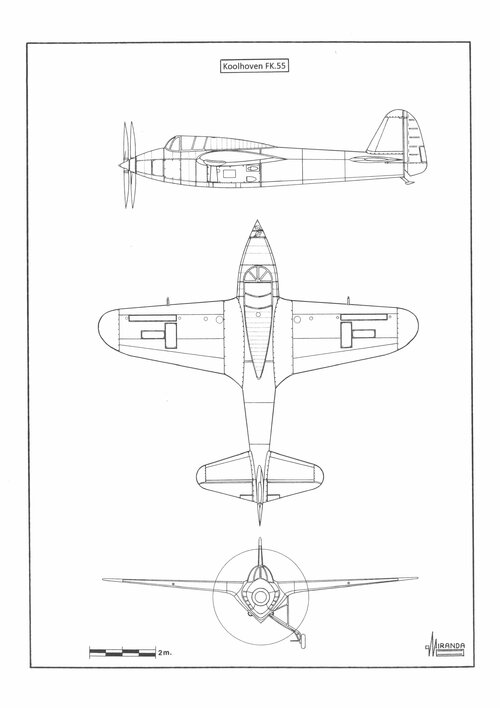

From 1935 the Koolhoven firm had tried to compete with Fokker using radical aerodynamic solutions.

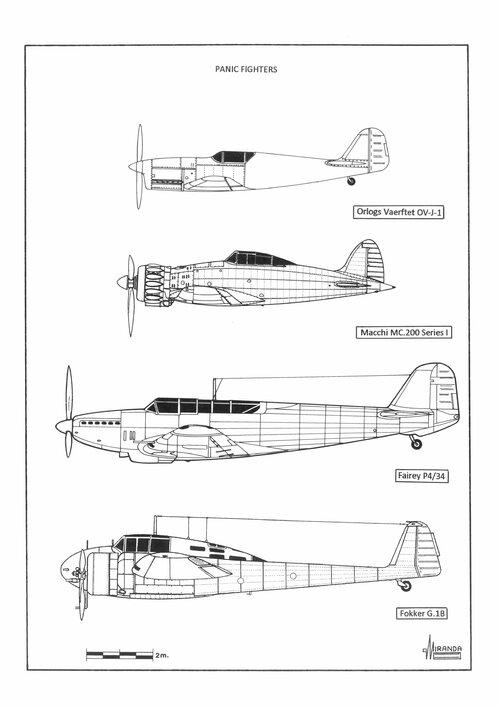

In November 1936 it presented the mock-up of an advanced fighter at the Salon de l'Aviation in Paris. It had slot-spoilers (instead of conventional ailerons), retractable landing gear and in-line engine, mounted behind the cockpit, driving contra-props via an extension shaft. A prototype was built in 1938 with conventional ailerons and 9 m wingspan, solely to test the operation of the power system. It took its first flight on 30 June, powered by an 860 hp Lorraine 12 Hars Petrel, suffering insurmountable problems with the Duplex reduction gear and the engine cooling system. The prototype was destroyed on 10 May 1940 during the bombing of the Koolhoven factory.

The production version, called Koolhoven FK.55, with 9.60 m wingspan, 9.25 m overall length and 16 sq. m wing surface, would have had an estimated maximum speed of 520 kph (powered by one 1,200 hp Lorraine Sterna) and 2,100 kg gross weight. It would have had a 20 mm Oerlikon cannon firing through the hub propellers and two 7.7 mm machine guns in the wings.

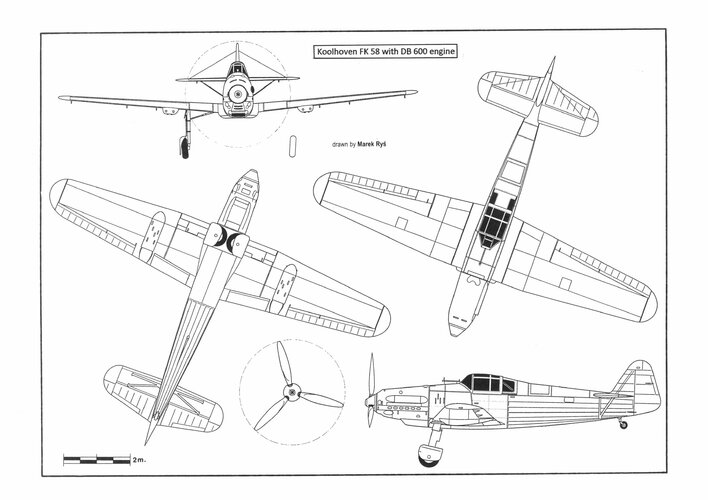

At the beginning of 1938 the engineer Van der Eyk designed the FK.58, a more conventional fighter able to fly at 500 kph powered by a Daimler-Benz DB 600. But the Munich Agreement cancelled the availability of German engines and Koolhoven was forced to start the production of the FK.58 using Gnôme-Rhône 14 N-39 radial engines that allowed a maximum speed of 475 kph only.

Historical circumstances converted the FK.58 into the 'panic fighter' that everyone wanted in 1939. On January the French acquired the eighteen aircraft that had been manufactured, four of them with 1,080 hp Hispano-Suiza 14 Aa radial engines and four 7.62 mm FN/Browning machine guns. On 22 July the Dutch Government commissioned the production of a new series of 26 aircraft with 1,060 hp Bristol Taurus III radial engines, but the British cancelled their export (March 2, 1940) using them to propel the Beaufort bombers. Ten more units that had been manufactured by S.A.B.C.A. in Belgium were destroyed by the Luftwaffe on 10 May.

Yugoslavia commissioned the manufacturing in France of forty aircraft and Finland of another forty-six, but the rapid development of the Blitzkrieg ended all these plans.

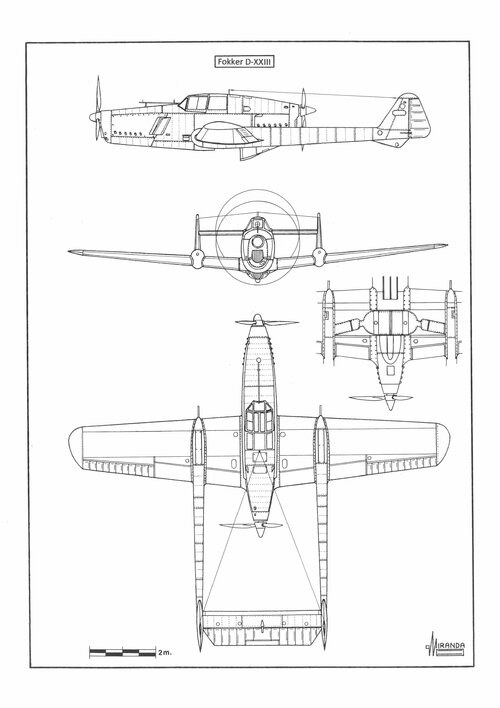

The lack of indigenous aircraft engines was the main limitation of the Dutch aeronautical industry. When Fokker started the design of the successor of the D.XXI at the end of 1937, he made it considering that, in any future European war, it would be difficult to access the powerful 1,000 hp engines that were already being manufactured in Germany, France and Great Britain.

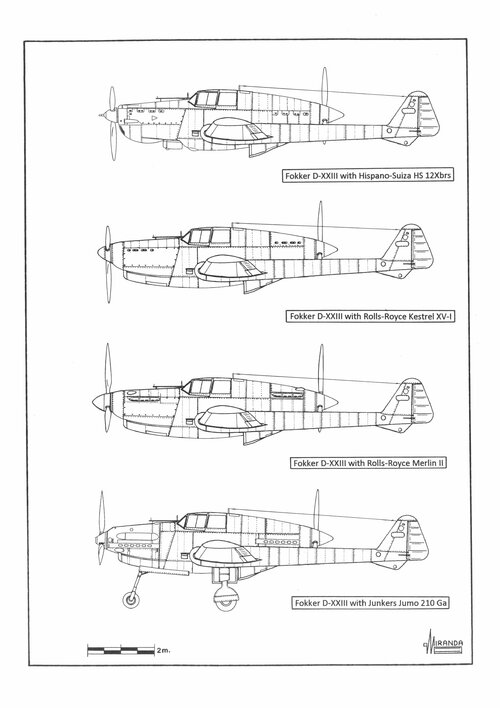

It was decided that the Fokker D.XXIII would be powered by two 500-700 hp engines, allowing to increase the CAP range using only one of them. A twin tail booms airframe, with short wingspan and tandem engines, was then chosen to obtain a fast aircraft. This configuration neutralised the gyroscopic coupling of the propellers and the power plants torque effect, giving the D.XXIII superior manoeuvrability compared to the Bf 110 and Potez 63 conventional twin-engine fighters. The D.XXIII could indistinctly use air-cooled engines of the types of Walter Sagitta I.S.R. (528 hp), Isotta-Fraschini Delta (700 hp), Gnôme-Rhône 14 M-4 (700 hp) or liquid-cooled Rolls-Royce Kestrel V (755 hp), Hispano-Suiza H.S.12 Xcrs (690 hp) and Junkers Jumo 210 Ga (745 hp).

The project Ontwerp 156 was also considered. It was a version of the D.XXIII propelled by two 1,030 hp Rolls-Royce Merlin II which would have been the fastest fighter of its time.

The D.XXIII prototype flew for the first time in May 1937, surpassing the 500 kph and 9,000 m ceiling, propelled by two Walter Sagitta. Hit by a bomb on 10 May 1940, it never flew again.

The construction system of the airframe was the same than that of the D.XXI, but the idea was to use a wing entirely built of metal for the production version. It was armed with two 7.9 mm (synchronized) machine guns in the fuselage and two 13.2 mm FN/Browning heavy machine guns in the tail booms.

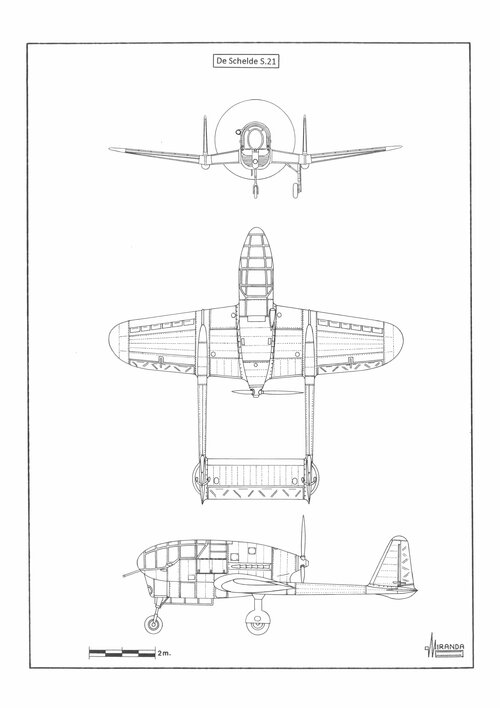

In opposition to the 'low tech' policy of Fokker, the De Schelde firm decided to enter the market of the fighters in 1938 with the S.21, a sophisticated twin tail booms design built entirely of metal, spanning 8.5 m, and incorporating several innovatory features. It would have been powered by a 1,050 hp DB 600 Ga, 12-cylinder inverted-Vee German engine driving a three bladed VDM, controllable-pitch, pusher propeller.

The armament would have consisted of one 7.9 mm MG 17 machine gun rear-firing through the propeller hub, for deterrent purposes, four 7.9 mm FN/Browning forward-firing machine guns and one flexibly mounted 20 mm Solothurn Tankbüsche S18-350 anti-tank cannon. During low-level attack, an automatic stabilising system controlling the ailerons and elevator, the pilot just had to operate the rudder to aim the cannon, which could be set in two positions: horizontal and 25 degrees downwards. The pilot used a retractable periscope to aim the MG 17. The propeller could be detached using explosive bolts when the pilot had to bail out.

The S.21 was expected to have excellent manoeuvrability and flight stability, due to the use of fixed wing slots and the position of the engine, installed over the CG. It was decided to change the engine to a 1,360 hp DB 601 Aa, with turbocharger, in March 1940, to improve performance at high altitude. The prototype c/n 58 was captured by the Wehrmacht in May. The production version, with DB 601 Aa, would have had an estimated maximum speed of 590 kph and 10,000 m ceiling.

en.wikipedia.org