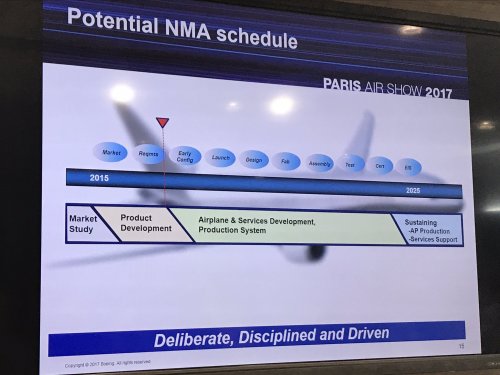

The drumbeat for a new Boeing midsize jetliner is growing louder. The recent ISTAT and Speednews conferences saw constant references to the new jet, which will seat 220-260 passengers with 5,000-5,500-nm range. Air Lease Corp. Executive Chairman Steven Udvar-Hazy even gave it a proper Boeing designation: the 797.

Given Boeing’s worsening disadvantage versus Airbus in the jetliner middle market, and given the company’s tendency to rest on its laurels and take long product-development holidays, the prospect of a new jet is very welcome news. But beyond the idea of a new Boeing aircraft, things get complicated. The 797’s twin-aisle configuration is the big issue.

First, there’s the market. Any projection of trends over the past 30 years—airliner fleets, orders and deliveries—clearly shows that single-aisle middle-market jets have enjoyed stronger growth than twin-aisle middle market jets. The mid-market demand ratio is now at least 3:1 in favor of single-aisles.

This explains the A321neo order book: about 1,400 aircraft. It also may explain why orders for 250-seat twin-aisles—particularly the 787-8 and A330-800—have been eclipsed by orders for larger variants. Norwegian’s recently announced plans to start transatlantic service with 737 MAXs, along with the increased number of other transatlantic single-aisle routes, suggest that, if anything, some twin-aisle midsize demand will migrate downward.

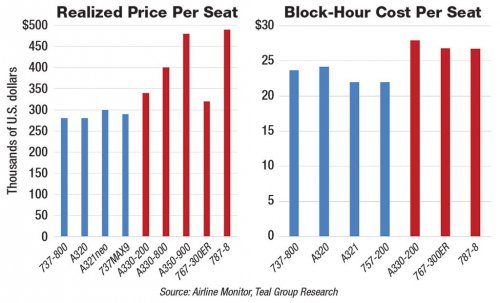

Second, there are the higher costs associated with twin-aisles. A glance at operating and production economics (block hour cost per seat and realized price per seat, respectively) clearly shows that there’s a significant gap between single- and twin-aisle jets. A single-aisle product is inherently cheaper to buy, build and fly. Low-cost carriers seeking fast turnaround times may like the idea of two aisles, in theory. But if twin-aisle operating economics remain distinctly higher than single-aisles’, it is unlikely that faster turnaround times will actually trump lower operating costs.

Boeing is aware of this problem. Company representatives have made it clear that the 797 needs to offer twin-aisle capabilities—range, comfort, capacity, and faster turnaround time—with single-aisle economics.

If Boeing is successful with this, they will have a product that likely stimulates demand in the mid-market twin-aisle segment. This is a reasonable goal. One big reason that orders for the 787 and Airbus A330neo series have migrated to the larger members of these families is that these aircraft are built with the structures and systems needed for longer routes and larger models. A plane that’s optimized for the shorter and lighter routes, like the 797, should convince airlines to fly new thinner routes between new city pairs.

But there are no guarantees that Boeing will be able to bridge the cost gap between single- and twin-aisle jets with the 797. And new technologies developed for the 797—particularly new engine technologies—could be used to help lower single-aisle operating costs, too, keeping the gap in place.

We might then see an echo of the late 1970s. At the time, Boeing concluded that the middle jetliner market really needed two products. The single-aisle 757 was introduced at about the same time as the twin-aisle 767, and the manufacturer sought commonality between the two types wherever possible. This time, Boeing is clearly looking at the 797 to play the 767’s role, while developing the 737-10 to do the 757 job.

The problem, though, is that the market views Airbus’s A321neo as better able to replace the 757. And while Boeing could change course and make the 797 a new single-aisle jet, that would imply the 737 MAX would merely be an interim product. Orders would take a serious hit. Also, Boeing might find it difficult to differentiate a new large single-aisle from the A321neo, turning this segment into a low-profit commodity product battlefield.

Therefore, Boeing will likely press ahead with the twin-aisle 797. The company can only hope that it reduces costs enough to stimulate demand in this segment. Otherwise, it’s quite possible that the 797 will get the bulk of the smaller twin-aisle middle market, while the A321neo continues to get the overwhelming majority of the much larger single-aisle middle market.