This is a risk. I know however that Australian Industry is trying to assist with capacity and the like.Regardless of how much support there is for AUKUS in the US, the fact is that the necessary investments in the submarine industrial base are not being made. Sub construction is falling further and further behind schedule. If investments aren't made to expand production and shipyard capacity during this next administration, I don't think the Virginias for Australia will exist.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

AUKUS Treaty NEWS ONLY

- Thread starter Rhinocrates

- Start date

- Joined

- 4 July 2010

- Messages

- 2,516

- Reaction score

- 3,107

Investments are being made but slowly and held back by Congress' inability to pass a budget. Both major sub yards have been expanding their production capabilities, and Austal has taken on submarine work in support of GD and HII. SSN production has risen above 1.3 boats/year while SSBN production has started. It's not where we want it to be, we wanted to be at 1.5 this year, and it will still take time and money to get there. But describing it as "nothing is being done" and "no investments are being made" is not correct. Failure to acknowledge the reality of the issue is exactly how we got here and we cannot continue to do that going forward.Regardless of how much support there is for AUKUS in the US, the fact is that the necessary investments in the submarine industrial base are not being made. Sub construction is falling further and further behind schedule. If investments aren't made to expand production and shipyard capacity during this next administration, I don't think the Virginias for Australia will exist.

I don't think Australia initiated the treaty, you ever heard of Scott Morrison?

This process was done in the shadows and blindsided the French.

Now Scotty has a new job as well.

The current government is stuck with the gig

www.afr.com

www.afr.com

Regards,

This process was done in the shadows and blindsided the French.

Now Scotty has a new job as well.

The current government is stuck with the gig

Inside Labor’s angst over AUKUS

Labor’s opposition to the Vietnam War and 2003 Iraq invasion may have cost it two elections, but they were the right calls, writes former senator Kim Carr in his new book.

Regards,

Scott Morrison was PM and thus represented Australia. this was a Government initiative, not one man's.I don't think Australia initiated the treaty, you ever heard of Scott Morrison?

And so??This process was done in the shadows and blindsided the French.

The current government is stuck with the gig

And they were in support of it whilst in Opposition and have done nothing to reverse it despite now being in power for the best part of 3yrs. Having spoken to numerous senior Government officials, including ministerial level, I can assure you that there is no intention to reverse course..

Of course, current labor ministers have to tow the party line, I am assuming you understand politics.

www.theguardian.com

www.theguardian.com

Of course there are many more against it.

You indicated previously that the majority of Australians want AUKUS. And ~61% say they 'somewhat' or 'strongly' support Australia using nuclear power to generate electricity to bring down domestic power prices.

Yet cannot seem to grasp that it will do nothing for the current prices and if it even occurs will be 30+ years away.

Not sure what that says about polling, Australians and majorities?

Since your so for AUKUS you must not be Australian, correct? As most Australians I know are not for it.

This relates directly to our sovereignty and economy.

Regards,

Former Labor foreign minister Gareth Evans says Australia won’t have sovereignty over Aukus submarines

Evans says Anthony Albanese should have reviewed Aukus when he came to power in 2022 and that the PM is too risk-averse

Of course there are many more against it.

You indicated previously that the majority of Australians want AUKUS. And ~61% say they 'somewhat' or 'strongly' support Australia using nuclear power to generate electricity to bring down domestic power prices.

Yet cannot seem to grasp that it will do nothing for the current prices and if it even occurs will be 30+ years away.

Not sure what that says about polling, Australians and majorities?

Since your so for AUKUS you must not be Australian, correct? As most Australians I know are not for it.

This relates directly to our sovereignty and economy.

Regards,

Last edited:

I must say I'm impressed not too many people can tell where a person is from based on the degree to which agree or disagree.... you're, you're special!Of course, current labor ministers have to tow the party line, I am assuming you understand politics.

Former Labor foreign minister Gareth Evans says Australia won’t have sovereignty over Aukus submarines

Evans says Anthony Albanese should have reviewed Aukus when he came to power in 2022 and that the PM is too risk-aversewww.theguardian.com

Of course there are many more against it.

You indicated previously that the majority of Australians want AUKUS. And ~61% say they 'somewhat' or 'strongly' support Australia using nuclear power to generate electricity to bring down domestic power prices.

Yet cannot seem to grasp that it will do nothing for the current prices and if it even occurs will be 30+ years away.

Not sure what that says about polling, Australians and majorities?

Since your so for AUKUS you must not be Australian, correct? As most Australians I know are not for it.

This relates directly to our sovereignty and economy.

Regards,

Should see what I can do with a deck of cards  .

.

"First, over recent years Australia has been witnessing the formation of what Lancaster University academic Andrew Chubb dubs a ‘coalition of securitisers’, comprising politicians, intelligence officials and journalists. The work of this coalition has significantly primed public opinion, making it easier to render the AUKUS agreement palatable to the public by actively promoting a narrative of the ‘China threat’."

"Acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines under AUKUS: Nearly half of Australians (48 percent) agreed that ‘The Australian government’s plan to acquire nuclear submarines under the Australia–UK–US (AUKUS) trilateral security partnership will help keep Australia secure from a military threat from China’, a four-point increase from when the view was first measured in 2023 (44 percent)."

Regards,

"First, over recent years Australia has been witnessing the formation of what Lancaster University academic Andrew Chubb dubs a ‘coalition of securitisers’, comprising politicians, intelligence officials and journalists. The work of this coalition has significantly primed public opinion, making it easier to render the AUKUS agreement palatable to the public by actively promoting a narrative of the ‘China threat’."

"Acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines under AUKUS: Nearly half of Australians (48 percent) agreed that ‘The Australian government’s plan to acquire nuclear submarines under the Australia–UK–US (AUKUS) trilateral security partnership will help keep Australia secure from a military threat from China’, a four-point increase from when the view was first measured in 2023 (44 percent)."

Regards,

Last edited:

I am not going to bother wasting my time picking apart your comments especially as they pertain to me personally. I will just say however that you should realise that I am an Australian, have served in the ADF, am very very cognisant of Australian politics (including having dealt directly with those of ministerial level) and continue to operate within the Australian Defence environment.Of course, current labor ministers have to tow the party line, I am assuming you understand politics.

Former Labor foreign minister Gareth Evans says Australia won’t have sovereignty over Aukus submarines

Evans says Anthony Albanese should have reviewed Aukus when he came to power in 2022 and that the PM is too risk-aversewww.theguardian.com

Of course there are many more against it.

You indicated previously that the majority of Australians want AUKUS. And ~61% say they 'somewhat' or 'strongly' support Australia using nuclear power to generate electricity to bring down domestic power prices.

Yet cannot seem to grasp that it will do nothing for the current prices and if it even occurs will be 30+ years away.

Not sure what that says about polling, Australians and majorities?

Since your so for AUKUS you must not be Australian, correct? As most Australians I know are not for it.

This relates directly to our sovereignty and economy.

Regards,

It is obvious you don't like AUKUS. We get it. This is supposed to be a thread about AUKUS news not your opinions on it. If you have news than post it, otherwise stop polluting the thread.

President Trump and Australia's National Security

Australia needs to try and persuade the Trump Administration that no country can expect to dominate our region and the benefits of cooperation. But if, as is likely, Trump refuses to accept a multipolar region then Australia must be prepared to act on its own and seek its security within Asia.

johnmenadue.com

Regards,

- Joined

- 19 July 2016

- Messages

- 4,292

- Reaction score

- 3,477

Well, every pearl starts with a grain of sand stuck somewhere.....

The problem is

President Trump and Australia's National Security

Australia needs to try and persuade the Trump Administration that no country can expect to dominate our region and the benefits of cooperation. But if, as is likely, Trump refuses to accept a multipolar region then Australia must be prepared to act on its own and seek its security within Asia.johnmenadue.com

Regards,

Michael is bonkers if he believes it is possible for China to operate that way. They do not respect the rule of law and the globe knows this, the evidence is beyond doubt. Michael has conveniently decided to ignore that possibility. In the context of Australia, if you know one big bully doesn't play nice with its neighbours then perhaps it is better to be friendly with the other bully that at least has a slightly better record.Australia should do its best to persuade the Trump Administration that it is in America’s interests to accept that China is an equally powerful neighbour that isn’t going to go away, and that there are major benefits from restoring the necessary protocols that allow peaceful cooperation in our region and where America would continue to have a major leadership role

Forest Green

ACCESS: Above Top Secret

- Joined

- 11 June 2019

- Messages

- 9,586

- Reaction score

- 17,689

Aussies announce $163M more for AUKUS initiatives, experts skeptical of 'substance' - Breaking Defense

"The Albanese Government must not continue to treat the Australian public as bystanders in our own security dialogue, and repackaging or dusting off old announcements is borderline offensive," Elizabeth Buchanan, a senior fellow at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, told Breaking Defense.

Trump 2.0: new deals on AUKUS and defence spending - Strategic Analysis Australia

Strategic Analysis Australia

strategicanalysis.org

strategicanalysis.org

Regards,

Last edited:

AUKUS Navies Trial Hugin Drone for Underwater Missions

The UK Royal Navy has partnered with its US and Australian counterparts to assess the Hugin system’s effectiveness in underwater warfare.

thedefensepost.com

thedefensepost.com

Regards,

- Joined

- 9 October 2009

- Messages

- 22,041

- Reaction score

- 13,744

Australia continues to support local industry to join AUKUS submarine supply chains - Naval News

The Australian Government is investing an additional $262 million to support local defence industry and develop Australia’s AUKUS nuclear-powered submarine supply chain.

Scott Kenny

ACCESS: USAP

- Joined

- 15 May 2023

- Messages

- 11,737

- Reaction score

- 14,525

This is honestly really good. Highly skilled welders, various engineers, a whole pile of precision equipment manufacturing, all means good wages and jobs, which then means that they have more money to spend in the community.

Australia continues to support local industry to join AUKUS submarine supply chains - Naval News

The Australian Government is investing an additional $262 million to support local defence industry and develop Australia’s AUKUS nuclear-powered submarine supply chain.www.navalnews.com

This is honestly really good. Highly skilled welders, various engineers, a whole pile of precision equipment manufacturing, all means good wages and jobs, which then means that they have more money to spend in the community.

The unnerving truth about how Australia will pay for its new nuclear submarines

To pay for megaprojects like Australia's new nuclear submarine program, or the COVID-era JobKeeper scheme, the Government has to find an awful lot of money from somewhere. Or does it? Peter Martin explains.

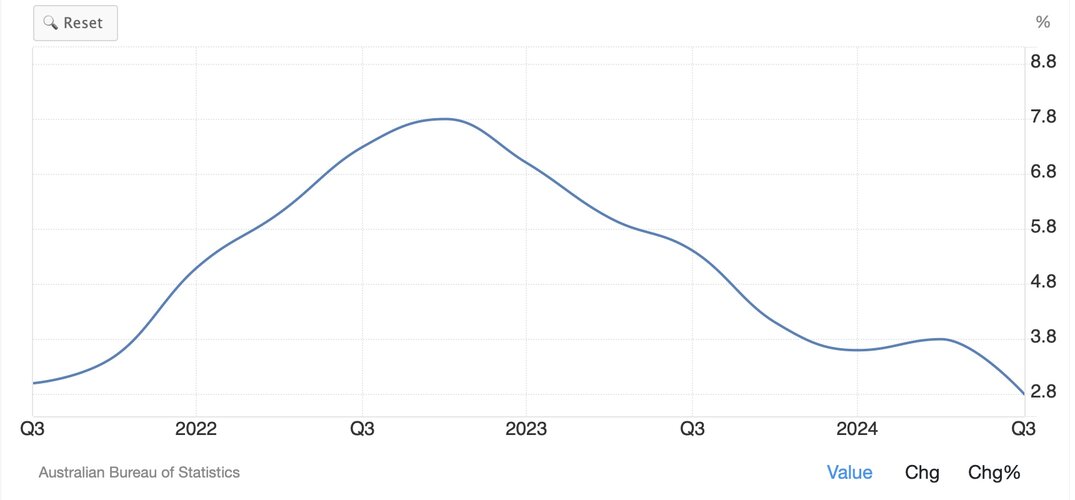

Unfortunately, not, we are already experiencing high inflation, and an increase in jobs and wages boosts household incomes, which, in turn, drives up consumer spending. This rise in spending increases aggregate demand, providing businesses with more opportunities to raise the prices of their goods and services. When this pattern is widespread across various industries and sectors, it contributes to a further rise in inflation.

Already our $ has fallen to ~0.63 due to falling demand by China for our exports meaning that imports cost more across the board which also increases inflation.

If the RBA cuts interest rates next meeting, then our $ will fall further.

The current AUS govt is being hounded by the coalition (AUKUS instigators) for ongoing spending as it is inflationary.

Regards,

Last edited:

I know some of the companies involved providing their capabilities to this effort.This is honestly really good. Highly skilled welders, various engineers, a whole pile of precision equipment manufacturing, all means good wages and jobs, which then means that they have more money to spend in the community.

Just note that this story is from nearly 2yrs ago...just in case anyone thought it was new.

The unnerving truth about how Australia will pay for its new nuclear submarines

To pay for megaprojects like Australia's new nuclear submarine program, or the COVID-era JobKeeper scheme, the Government has to find an awful lot of money from somewhere. Or does it? Peter Martin explains.www.abc.net.au

Hmmm...2.8% currently:Unfortunately, not, we are already experiencing high inflation,

So you don't want an increase in jobs and wages??and an increase in jobs and wages boosts household incomes, which, in turn, drives up consumer spending. This rise in spending increases aggregate demand, providing businesses with more opportunities to raise the prices of their goods and services. When this pattern is widespread across various industries and sectors, it contributes to a further rise in inflation.

Lower exchange rates also greatly help our exports.Already our $ has fallen to ~0.63 due to falling demand by China for our exports meaning that imports cost more across the board which also increases inflation.

Not necessarily. even if it does, are you saying you don't want interest rates to be cut??If the RBA cuts interest rates next meeting, then our $ will fall further.

It's an election year. The Opposition will hound the Govt no matter what the topic or the decision...The current AUS govt is being hounded by the coalition (AUKUS instigators) for ongoing spending as it is inflationary.

Once again, the idea that a lower dollar is beneficial needs rethinking. Australia’s two largest exports, iron ore (Fe) and coal, make up over 30% of our total exports. Yet, Australia runs a current account deficit, meaning we import more than we export. So how does a lower dollar help when it creates more problems than it solves?

When Fe and coal prices were at their previous highs—$212 USD ($271 AUD) and $457 USD ($585 AUD), respectively, the AUD was trading at around $0.78. Now, with prices down to $101 USD ($160 AUD) and $116 USD ($193 AUD), the AUD has dropped to $0.62 or a ~23% fall in the same period.

Since Fe and coal prices have a high correlation with the AUD, weaker demand causes both commodity prices and the AUD to fall. This creates a considerable revenue problem. To maintain the same revenue, we would need to sell far higher volumes of both Fe and coal. But that’s not happening.

Even if an exporter increased exports by 10% (which is a significant jump) they would still see a 13% loss in revenue due to the lower AUD. Factor in rising manufacturing costs (e.g., 5%), and exporters are worse off overall. A weaker dollar doesn’t compensate for falling demand or lower prices—it amplifies the pain.

Meanwhile, imports get more expensive, and Australia imports a lot. Here are just some of the big ticket items:

Petroleum oils (not crude): $50.75 billion

Motor vehicles (passenger): $34.8 billion

Electrical apparatus for telephony: $12.95 billion

Medicines: $8.96 billion

Crude petroleum oils: $7.96 billion

With a weaker AUD, all these imports cost more, pushing inflation higher. Higher inflation means the Reserve Bank will likely raise interest rates, adding more pressure on households and businesses.

www.rba.gov.au

www.rba.gov.au

On top of that, Australia raises a significant amount of funding from offshore debt markets. A lower AUD increases repayment costs, putting even more strain on the economy.

So, even if demand for exports increases, falling prices and higher costs mean exporters earn less. Meanwhile, higher import costs drive inflation and debt servicing costs higher. In short, a lower AUD doesn’t help—it hurts.

Australia does not even make cars anymore, yet all of a sudden, we can build nuclear subs?

Yes, I do not want rate drops, I am more concerned about the next 12–24 months than some hypothetical trillion dollar, 30+yr pipe dream. Cutting interest rates now would only make inflation worse and create further instability.

Regards,

When Fe and coal prices were at their previous highs—$212 USD ($271 AUD) and $457 USD ($585 AUD), respectively, the AUD was trading at around $0.78. Now, with prices down to $101 USD ($160 AUD) and $116 USD ($193 AUD), the AUD has dropped to $0.62 or a ~23% fall in the same period.

Since Fe and coal prices have a high correlation with the AUD, weaker demand causes both commodity prices and the AUD to fall. This creates a considerable revenue problem. To maintain the same revenue, we would need to sell far higher volumes of both Fe and coal. But that’s not happening.

Even if an exporter increased exports by 10% (which is a significant jump) they would still see a 13% loss in revenue due to the lower AUD. Factor in rising manufacturing costs (e.g., 5%), and exporters are worse off overall. A weaker dollar doesn’t compensate for falling demand or lower prices—it amplifies the pain.

Meanwhile, imports get more expensive, and Australia imports a lot. Here are just some of the big ticket items:

Petroleum oils (not crude): $50.75 billion

Motor vehicles (passenger): $34.8 billion

Electrical apparatus for telephony: $12.95 billion

Medicines: $8.96 billion

Crude petroleum oils: $7.96 billion

With a weaker AUD, all these imports cost more, pushing inflation higher. Higher inflation means the Reserve Bank will likely raise interest rates, adding more pressure on households and businesses.

In Brief: Statement on Monetary Policy – November 2024

In Brief: Statement on Monetary Policy – November 2024

On top of that, Australia raises a significant amount of funding from offshore debt markets. A lower AUD increases repayment costs, putting even more strain on the economy.

So, even if demand for exports increases, falling prices and higher costs mean exporters earn less. Meanwhile, higher import costs drive inflation and debt servicing costs higher. In short, a lower AUD doesn’t help—it hurts.

Australia does not even make cars anymore, yet all of a sudden, we can build nuclear subs?

Yes, I do not want rate drops, I am more concerned about the next 12–24 months than some hypothetical trillion dollar, 30+yr pipe dream. Cutting interest rates now would only make inflation worse and create further instability.

Regards,

Last edited:

If you read what I said was "Lower exchange rates also greatly help our exports." This is definitely the case.Once again, the idea that a lower dollar is beneficial needs rethinking. Australia’s two largest exports, iron ore (Fe) and coal, make up over 30% of our total exports. Yet, Australia runs a current account deficit, meaning we import more than we export. So how does a lower dollar help when it creates more problems than it solves?

Blah, blah, blah....off topic. Please try to stay on topic. As already stated, it is obvious you don't like AUKUS. We get it. This is supposed to be a thread about AUKUS news not your opinions on it. If you have news then post it, otherwise stop polluting the thread.When Fe and coal prices were at their previous highs—$212 USD ($271 AUD) and $457 USD ($585 AUD), respectively, the AUD was trading at around $0.78. Now, with prices down to $101 USD ($160 AUD) and $116 USD ($193 AUD), the AUD has dropped to $0.62 or a ~23% fall in the same period.

Since Fe and coal prices have a high correlation with the AUD, weaker demand causes both commodity prices and the AUD to fall. This creates a considerable revenue problem. To maintain the same revenue, we would need to sell far higher volumes of both Fe and coal. But that’s not happening.

Even if an exporter increased exports by 10% (which is a significant jump) they would still see a 13% loss in revenue due to the lower AUD. Factor in rising manufacturing costs (e.g., 5%), and exporters are worse off overall. A weaker dollar doesn’t compensate for falling demand or lower prices—it amplifies the pain.

Meanwhile, imports get more expensive, and Australia imports a lot. Here are just some of the big ticket items:

Petroleum oils (not crude): $50.75 billion

Motor vehicles (passenger): $34.8 billion

Electrical apparatus for telephony: $12.95 billion

Medicines: $8.96 billion

Crude petroleum oils: $7.96 billion

With a weaker AUD, all these imports cost more, pushing inflation higher. Higher inflation means the Reserve Bank will likely raise interest rates, adding more pressure on households and businesses.

In Brief: Statement on Monetary Policy – November 2024

In Brief: Statement on Monetary Policy – November 2024www.rba.gov.au

On top of that, Australia raises a significant amount of funding from offshore debt markets. A lower AUD increases repayment costs, putting even more strain on the economy.

So, even if demand for exports increases, falling prices and higher costs mean exporters earn less. Meanwhile, higher import costs drive inflation and debt servicing costs higher. In short, a lower AUD doesn’t help—it hurts.

Has anyone said anywhere about "all of a sudden"? The building of the first boat is to begin by the end of the 2030s with the boat delivered in the early 2040s.yet all of a sudden, we can build nuclear subs?

Michael is bonkers if he believes it is possible for China to operate that way. They do not respect the rule of law and the globe knows this, the evidence is beyond doubt. Michael has conveniently decided to ignore that possibility. In the context of Australia, if you know one big bully doesn't play nice with its neighbours then perhaps it is better to be friendly with the other bully that at least has a slightly better record.

This is my admittedly American take on it, for most any country on top of Australia. The only thing worst than US global hegemony is pretty much anything that replaces it. The last century has been, by great power historical standards, relatively peaceful. Freedom of navigation has never been a given before. There’s no reason to assume it will exist when the U.S. is no longer able to enforce it, most especially inside the 9 dashed line.

China’s dealings with Australia seem rather unfriendly despite being its largest trade partner.

Australia–China trade war - Wikipedia

Last edited:

Trump Administration’s Defense Chief reaffirms US Commitment to AUKUS in Talks with Australia

Trump Administration’s Defense Chief reaffirms US Commitment to AUKUS in Talks with Australia.

Forest Green

ACCESS: Above Top Secret

- Joined

- 11 June 2019

- Messages

- 9,586

- Reaction score

- 17,689

'More work to be done' to lower barriers to tech-sharing for AUKUS Pillar II, Australian official says - Breaking Defense

The problem lies within the Excluded Technology List (ELT), a list of tech that is not eligible for transfer under the existing AUKUS exemptions.

ADT and Penten progress in AUKUS EW challenge - Australian Defence Magazine

Canberra companies Advanced Design Technology and Penten have been awarded contracts worth a total of more than $8 million to continue developing electronic warfare technology for Defence and the AUKU...

www.australiandefence.com.au

www.australiandefence.com.au

Trump’s tariff plan attacked in Congress as ‘insult to Australians’

At least one US legislator has lambasted the president’s intention to slug Australian steel and aluminum imports into America.

500 mil down the drain......................

If only the AUS govt waited a week.

Regards,

Forest Green

ACCESS: Above Top Secret

- Joined

- 11 June 2019

- Messages

- 9,586

- Reaction score

- 17,689

It seems Trump has things confused. You're not supposed to impose economic sanctions on your allies.

- Joined

- 15 July 2007

- Messages

- 4,890

- Reaction score

- 4,568

Although the following is not directly AUKUS related, and yes it does have all sorts of domestic politics goingon in this..... It does show the direction of travel in the UK's approach to resurrecting nuclear technology and production in the UK, as it does to the trend to increase training, and investment.

So it has some related relevance.

Government rips up rules to fire-up nuclear power

More nuclear power plants will be approved across England and Wales as the Prime Minister slashes red tape to get Britain building - as part of his Plan for Change.

www.gov.uk

www.gov.uk

More nuclear power plants will be approved across England and Wales as the Prime Minister slashes red tape to get Britain building - as part of his Plan for Change.

Reforms to planning rules will clear a path for smaller, and easier to build nuclear reactors – known as Small Modular Reactors –to be built for the first time ever in the UK. This will create thousands of new highly skilled jobs while delivering clean, secure and more affordable energy for working people.

So it has some related relevance.

Government rips up rules to fire-up nuclear power

More nuclear power plants will be approved across England and Wales as the Prime Minister slashes red tape to get Britain building - as part of his Plan for Change.

Government rips up rules to fire-up nuclear power

More nuclear power plants will be approved across England and Wales as the Prime Minister slashes red tape to get Britain building - as part of his Plan for Change.

More nuclear power plants will be approved across England and Wales as the Prime Minister slashes red tape to get Britain building - as part of his Plan for Change.

Reforms to planning rules will clear a path for smaller, and easier to build nuclear reactors – known as Small Modular Reactors –to be built for the first time ever in the UK. This will create thousands of new highly skilled jobs while delivering clean, secure and more affordable energy for working people.

When US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth was recently asked whether they'd be delivered on time, he said: "We sure hope so".

Regards,

Why not post the original story rather than the MSN copy - especially given you are from Australia:

Will AUKUS survive Trump? Defence experts and critics weigh in

Former PM Malcolm Turnbull believes AUKUS is a "one-sided", bad deal, although the security partnership has cross party support in Australia. So how could the arrival of new US president Donald Trump impact the deal?

Australian businesses benefitting from AUKUS reforms - APDR

Australian businesses are seeing the benefits of the export licence-free environment established with the United Kingdom and the US

Why not post the original story rather than the MSN copy - especially given you are from Australia:

I read it on MSN, very strange point. So, you're saying as an Australian I have to read ABC only.

ITAR is a bigger issue than most realise.

Regards,

Last edited:

- Joined

- 23 August 2011

- Messages

- 1,627

- Reaction score

- 4,818

Preliminary work to support AUKUS construction continues in the UK...

www.sheffieldforgemasters.com

www.sheffieldforgemasters.com

New landmark Machining facility at Sheffield Forgemasters gets go-ahead

- Joined

- 4 July 2010

- Messages

- 2,516

- Reaction score

- 3,107

Well he's planning to dial back sanctions on Russia, so maybe he does know thatIt seems Trump has things confused. You're not supposed to impose economic sanctions on your allies.

Flash News : US Prioritizes Delivery of Virginia-class Nuclear Submarines to Australia Under AUKUS Pact

Flash News: US Prioritizes Delivery of Virginia-class Nuclear Submarines to Australia Under AUKUS Pact

No I am not saying that. It was just that when you post a link from MSN all it shows on the forum is "MSN" which isn't helpful. Moreover, when opening it, it quickly becomes obvious that it is a simple repost of the ABC article.I read it on MSN, very strange point. So, you're saying as an Australian I have to read ABC only.

The treaty changes and associated legislation enacted last year have gone a long way to addressing this and are already in use

ITAR is a bigger issue than most realise.

WatcherZero

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 22 May 2023

- Messages

- 834

- Reaction score

- 1,947

Dont engage, there is a lot of paid Chinese posters on South East Asian news sites and forums trying to destroy AUKUS. It demonstrates how much the Chinese government recognises it as a threat.

Just look at Halycon66 post history, its nothing but negative news headlines except on Chinese aircraft threads and the usual Cryptobro buy bitcoin posts.

Just look at Halycon66 post history, its nothing but negative news headlines except on Chinese aircraft threads and the usual Cryptobro buy bitcoin posts.

Damn I have been outed............my real name is Low Fat

Pretty sure the Chinese know better than anyone that the chances of Aus getting subs when the US cannot even make them quick enough for themselves is that number less than one, zero I think they call it.

Some of us just don't drink the kool aid.

Regards,

Pretty sure the Chinese know better than anyone that the chances of Aus getting subs when the US cannot even make them quick enough for themselves is that number less than one, zero I think they call it.

Some of us just don't drink the kool aid.

Regards,

Last edited:

US congressional analysis blunt on AUKUS difficulties

A new budgetary report said it would be 'difficult and expensive' to sell Virginia class submarines to Australia without compromising the US Navy.

Regards,

Similar threads

-

-

Boris Johnson considered Netherlands incursion during Covid-19 pandemic

- Started by Grey Havoc

- Replies: 21

-

Could HMAS Australia have been saved from scrapping ?

- Started by Oberon_706

- Replies: 308

-

RAAF Wedgetail AEW&C proposals and early designs

- Started by Triton

- Replies: 1

-

Superstar engineer John Hart-Smith skewered Boeing’s strategy | Obituary

- Started by aim9xray

- Replies: 4