I'm rather sceptical that we can reliably estimate how a population may have responded to bombardment or air attack in 1918. Especially in the case of the USA who had been sheltered from direct outside attack since 1846 but whose older generations would still have remembered the carnage of the civil war. There was also a much larger German immigrant community in the USA, would they suffer backlash or would it temper the mob?

I'm not sure the Pearl Harbor analogy is applicable, there were other factors at stake there and any raid in 1918 would be during American's involvement as a belligerent.

The populations of some of the bigger coastal towns along Britain's East coast had endured shelling from German battlecruisers right on their doorstep. London and dozens of smaller places and little hamlets got caught up in the Zeppelin and Gotha raids.

There was anger, there were mobs smashing up shops which had any remotely German sounding name on them and in part this addition to the general anti-German loathing made one very famous family change their dynastic name to one of the castles they owned. We can't also ignore that a smooth propaganda machine swung into action, posters dubbing Zeppelin's as "baby killers" to stoke up public opinion.

Yet with hindsight, 51 Zeppelin raids unleashing 5,000 bombs would only kill 557 and injure 1,358 people, the Gotha's did far better in terms of casualties - 27 raids killing 835 and injuring 1,972. If anything this highlights how ineffective Zeppelins were.

But on the other hand, morale wasn't crushed, people didn't flee London, just as many who would hide would also stand and stare at the action overhead and some at the time this reluctance to shelter had increased casualties - even in 1940 people would often watch dogfights overhead as a form of entertainment.

There is a telling passage in John Buchan's

Mr Standfast, published in 1919 and describing Richard Hannay caught up in an air raid on London in late 1917, which was probably inspired by Buchan's own experiences in London around that time.

The man who says he doesn’t mind being bombed or shelled is either a liar or a maniac. This London air raid seemed to me a singularly unpleasant business. I think it was the sight of the decent civilised life around one and the orderly streets, for what was perfectly natural in a rubble-heap like Ypres or Arras seemed an outrage here. I remember once being in billets in a Flanders village where I had the Maire’s house and sat in a room upholstered in cut velvet, with wax flowers on the mantelpiece and oil paintings of three generations on the walls. The Boche took it into his head to shell the place with a long-range naval gun, and I simply loathed it. It was horrible to have dust and splinters blown into that snug, homely room, whereas if I had been in a ruined barn I wouldn’t have given the thing two thoughts. In the same way bombs dropping in central London seemed a grotesque indecency. I hated to see plump citizens with wild eyes, and nursemaids with scared children, and miserable women scuttling like rabbits in a warren.

The drone grew louder, and, looking up, I could see the enemy planes flying in a beautiful formation, very leisurely as it seemed, with all London at their mercy. Another bomb fell to the right, and presently bits of our own shrapnel were clattering viciously around me. I thought it about time to take cover, and ran shamelessly for the best place I could see, which was a Tube station. Five minutes before the street had been crowded; now I left behind me a desert dotted with one bus and three empty taxicabs.

I found the Tube entrance filled with excited humanity. One stout lady had fainted, and a nurse had become hysterical, but on the whole people were behaving well. Oddly enough they did not seem inclined to go down the stairs to the complete security of underground; but preferred rather to collect where they could still get a glimpse of the upper world, as if they were torn between fear of their lives and interest in the spectacle. That crowd gave me a good deal of respect for my countrymen. But several were badly rattled, and one man a little way off, whose back was turned, kept twitching his shoulders as if he had the colic.

It leavens the feeling of panic and puts the moral case rather interestingly, bringing the battlefield to 'civilised' London seemed repugnant, although we could point out the poor people of Ypres or Arras probably didn't think it natural to have their towns obliterated by artillery...

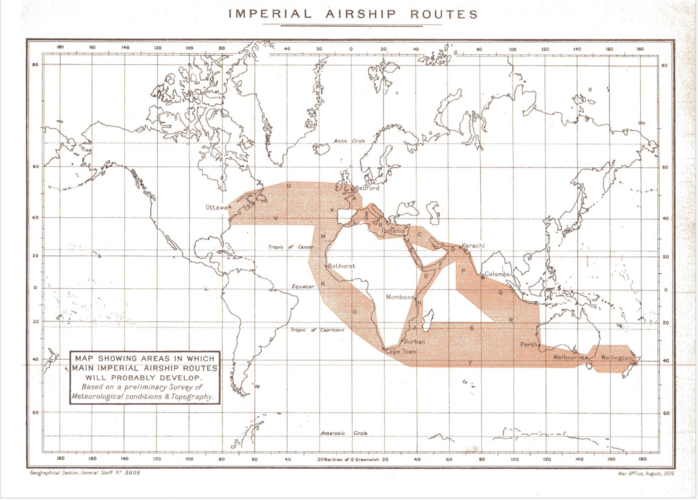

There is always a taste of exceptionalism, not a year before the novel was published Trenchard had wanted to meet out similar punishment on German cities with HP O/100s and O/400s and Vimys but the hundred. Likewise the USAAS was keen to build its own fleet of Handley Pages for strategic bombing.