WITHIN the next few months, the biggest defence contract for what will probably be many years to come will be awarded by the US Air Force, to build a new long-range strike bomber. The B-3, as it is likely to be named, will be a nuclear-capable aircraft designed to penetrate the most sophisticated air defences. The contract itself will be worth $50 billion-plus in revenues to the successful bidder, and there will be many billions of dollars more for work on design, support and upgrades. The plan is to build at least 80-100 of the planes at a cost of more than $550m each.

The stakes could not be higher for at least two of the three industrial heavyweights that are slugging it out. On one side is a team of Boeing and Lockheed Martin; on the other, Northrop Grumman. The result could lead to a shake-out in the defence industry, with one of the competitors having to give up making combat aircraft for good.

After the B-3 contract is awarded, the next big deal for combat planes—for a sixth-generation “air-dominance fighter” to replace the F-22 and F-18 Super Hornet—will be more than a decade away. So Richard Aboulafia of the Teal Group, an aviation-consulting firm, believes it will be hard for the loser to stay in the combat-aircraft business. If Northrop were to miss out, its investors may press for it to be broken up. If Boeing were to lose, Mr Aboulafia thinks it may seek to buy Northrop’s aircraft-building business, to ensure it gets the job after all. The production line in St Louis that makes Boeing’s F-18 (the US Navy’s mainstay fighter until it starts to get the carrier version of the new F-35 in numbers) is due to close in 2017. If Northrop were to depart the field, that could leave Lockheed Martin as the only American company with the ability to design combat planes, and thus the biggest winner of the three.

Usually in a contest of this kind, particularly this close to its end, a clear favourite emerges. Industry-watchers rate this one as still too close to call. That is partly because the degree of secrecy surrounding what is still classified as a “black programme” has remained high. Only the rough outlines of the aircraft’s specification have been revealed. It will be stealthy, subsonic, have a range of around 6,000 miles (9,650km) and be able to carry a big enough payload to destroy many targets during a single sortie. The best clues to what it will look like are from earlier “flying wing” design concepts the aircraft-makers have displayed, and from the shrouded “mystery plane” that Northrop showed in a recent television commercial (pictured). But most of all, picking a winner is hard because both competitors are highly credible—and each has different strengths.

Boeing and Lockheed first joined forces in 2007 to build what was then known as the Next-Generation Bomber—a project cancelled two years later because its excessive technological ambition was causing costs to soar. They decided to team up again in 2013 to prepare for a new request for proposals that the air force quietly released last summer. Boeing is the team leader and will build the aircraft if their bid is successful; Lockheed will take the main responsibility for its design.

That should be a winning combination. Boeing is as good as it gets when it comes to the efficient construction of large aircraft, and has painfully and expensively acquired expertise in carbon-fibre composites as it developed its 787 Dreamliner, a civil airliner. Lockheed can draw on its “skunk works”, an autonomous design team that works on radical new aircraft technologies; and on its experience developing radar-beating stealth technologies for the F-22 and F-35 fighter planes.

Northrop, on the other hand, built the revolutionary B-2 stealth bomber that entered service in the early 1990s. It was conceived as a deep-penetration nuclear bomber at the height of the cold war. But when the Soviet Union dissolved, the need for America to have 132 of the planes went with it. Only 21 were eventually built, leading the programme into a “death spiral” in which declining orders pushed up the unit price of an aircraft to absurd levels. Once its development, engineering and testing costs were added, each B-2 ended up costing more than $2 billion. But it was hardly Northrop’s fault that the cold war ended sooner than expected. The plane it built has since proved its capabilities in numerous conflicts, from Kosovo to Libya.

Updated versions of the once-radical technologies that made the B-2 so expensive (both to buy and to operate) will find their way into the new bomber. Another possible advantage for the air force in choosing Northrop is that it might be better able to focus on the programme. Boeing is not only grappling with its hugely demanding, and rapidly expanding, civil-aviation business; it is also struggling to deliver the K-46 tanker plane by the target date of 2017. (It snatched that big order from a consortium of Northrop and Airbus, after protesting at the air force’s initial decision to award it to its rivals.) Lockheed, for its part, also has its hands full ramping up production of the late and over-budget F-35.

The target for the plane to come into operation is the mid-2020s—if possible, even earlier. In part this is because of fast-emerging new threats and in part because the average age of America’s current bomber fleet, consisting of 76 geriatric B-52s, 63 B-1s and 20 B-2s, is 38 years. Keeping such ancient aircraft flying in the face of metal fatigue and corrosion is a constant struggle: just 120 are deemed mission-ready. None of these, except the B-2s, can penetrate first-rate air defences without carrying cruise missiles—and the missiles are of little use against mobile targets.

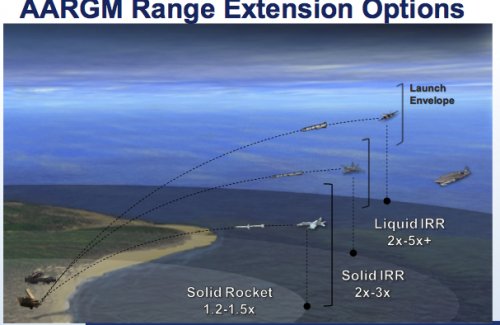

In the kind of one-sided wars that America and its allies fought in the years after the September 11th 2001 attacks, such deficiencies were not a problem. But during that period China, in particular, has invested heavily in “anti-access/area-denial” (A2/AD) capabilities. These include thousands of precision-guided missiles of increasing range that could threaten America’s bases in the Western Pacific, and any carriers sailing close enough to shore to launch their short-range tactical aircraft. Critics of the huge F-35 programme (the Pentagon is planning to buy 2,457 aircraft at a cost of around $100m each) argue that its limited range was a growing problem even before it entered service. A new long-range bomber that can penetrate the most advanced air defences is thus seen as vital in preserving America’s unique ability to project power anywhere in the world.

If getting the new bomber into service fast is a priority, so too is keeping the price low enough to be able to build it in sensible numbers, and thus keep it safe from political ambush. Budget caps imposed by Congress in 2013 have ushered in a decade of defence-spending austerity, and the B-3 will be the first major weapons system to be designed and produced in this new era.

To stay on budget and avoid the risk of having its orders cut, the programme will have to rely on technologies adapted from earlier projects; and any temptation to “gold-plate” its specification with showy but not strictly necessary features will have to be resisted. The B-3 will be a bit smaller than the B-2, and be able to use the same engines as the F-35. The option of being able to fly the bomber pilotlessly, by remote control, seems to have been dropped, as have some highly sophisticated surveillance sensors that were proposed earlier.

The risk of this cautious approach is that the new bomber might quickly lose its technical edge if faced with new threats or relentlessly improving air-defence systems (thanks to ever faster processors and sensors). But this danger is being seen off in two ways. The first is by designing the planes with what the Pentagon’s acquisitions chief, Frank Kendall, describes as an “open architecture and modular approach”, in which companies will compete to provide future upgrades that can be easily plugged in as and when needed. The other is that, despite its stealthiness, the B-3 will be fully connected to a range of “off-board capabilities”, such as electronic countermeasures and the collection of targeting data, provided by other aircraft and orbital reconnaissance satellites, instead of having to carry everything on board.

In keeping with the secrecy surrounding the plane, neither of the two competing teams is prepared to discuss their bids or why they should prevail in any detail. Such reticence may not survive the awarding of the contract. Although the air force is striving to make its decision as protest-proof as possible, neither Boeing nor Northrop is likely to take defeat quietly. Northrop is still smarting from Boeing’s lobbying triumph over the K-46 tanker programme, in which a plane that many military analysts considered superior ended up losing.

The Pentagon likes to share work around so as to ensure there is continued competition for contracts to provide military gear, especially complex ones such as this. In the case of the B-3 it has explicitly ruled out taking such concerns into account when choosing between the two contenders. That may be because it realises that whichever it selects, it will deal a devastating blow to the other. The days when America had a choice of combat-plane suppliers are coming to an end