Kendall Previews New Modernization Agenda For U.S. Air Force | Aviation Week Network

Experienced Pentagon veteran calls for return to a more conventional approach to innovation after era of open-ended demonstrations.

Newly confirmed U.S. Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall has called for doubling down on his predecessor’s wide-ranging modernization strategy to prepare for conflict with a rising Chinese military, but he brings a new style that emphasizes making disciplined progress over open-ended innovation plans.

In his first appearance at the Air Force Association’s annual Air, Space & Cyber Conference, the career Army officer, industry executive and Defense Department bureaucrat called for a more conventional approach to fielding the innovative technologies in the modernization portfolio, including a shift away from prioritizing Silicon Valley startups in lieu of traditional defense contractors and federal laboratories (AW&ST Sept. 13-26, p. 16).

An early target of the Air Force’s new approach to innovation is the Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS) program, a defining initiative of the era preceding Kendall’s appointment.

The Air Force first introduced the ABMS concept to Congress in 2017 as a potential replacement for the Boeing E-3 Airborne Warning and Control System, which includes an airborne moving target indication radar and battle management suite.

Noting that such large, slow and radiating platforms like the Boeing 707-based E-3 are increasingly vulnerable to a new class of long-range, anti-radiation missiles, Air Force officials—led by Will Roper, then-assistant secretary for acquisition, technology and logistics—proposed to replace the fleet with a distributed aerial network of sensors and automated battle management nodes.

But the concept quickly expanded. By 2018, Air Force leaders decided to shift the ABMS into the chosen successor for the Northrop Grumman E-8C Joint Stars (J-Stars), following the cancellation of the $6 billion J-Stars recapitalization program. Thus, the distributed ABMS network would replace the battle management capabilities of the E-8C. It was not immediately clear then how the Air Force would replace the E-8C’s wide-area surveillance radar with ground moving target indication (GMTI). But the U.S. Space Force partially declassified a new program this year that aims to field GMTI radars in orbit.

Under Roper’s guidance, the ABMS concept continued to expand. Instead of simply replacing the battle management functions of the E-3C or E-8C fleets, the Air Force repositioned ABMS as a sweeping architecture encompassing a new family of industry-built, government-owned airborne technologies, including radars, radios, data links, attritable unmanned aircraft systems, data processing systems and a combat cloud.

Roper further launched a series of open-ended “on-ramp” demonstrations in which dozens of new technologies and software-based applications could be assembled and tested quickly in real-world conditions. But the on-ramp events were consistently criticized by congressional oversight committees, which objected to the lack of a defined plan to usher the most promising technologies from the demonstrations into traditional programs of record.

As the Air Force’s top new civilian leader, Kendall appears to agree with the decision of the congressional committees. ABMS needs to be “focused on achieving and fielding specific measurable improvements in operational outcomes,” he says.

Even before Kendall’s Senate swearing-in ceremony in August, the Air Force was shifting the ABMS program yet again. In late January, one of Roper’s last acts in office was delivering a strategy to field the ABMS Capability Release (CR) 1. Instead of a broad, open-ended architecture, CR 1 aims to field a specific technology on the Boeing KC-46A tanker fleet. The original plan called for developing a new airborne networking system in spiral 1, a podded container in spiral 2 and a processing system in spiral 3 that would be capable of developing a fused, common operational picture from a multitude of sensor inputs collected by the data link.

The Air Force, however, has paused work on moving CR 1 into the acquisition system until Kendall completes a review of the new architecture.

Meanwhile, the Air Force has abandoned any trace of the original plan to replace the aging E-3 fleet with a distributed system. Although the Air Force completed what it had described as a “revolutionary” Block 40/45 upgrade program in 2020 for the E-3 mission computers and displays, the 31-aircraft fleet still faces a worsening reliability crisis.

As a result, Air Force leaders are pushing to launch an urgent program to acquire a new fleet of Boeing 737--derived E-7 airborne early warning and control aircraft. The urgency is partly driven by a possible production shutdown on Boeing’s 737 Next-Generation series assembly line in 2025, following the last delivery of the company’s P-8A maritime patrol aircraft. An E-7 procurement order by the Air Force in fiscal 2023 likely would help Boeing avoid a production pause or shutdown.

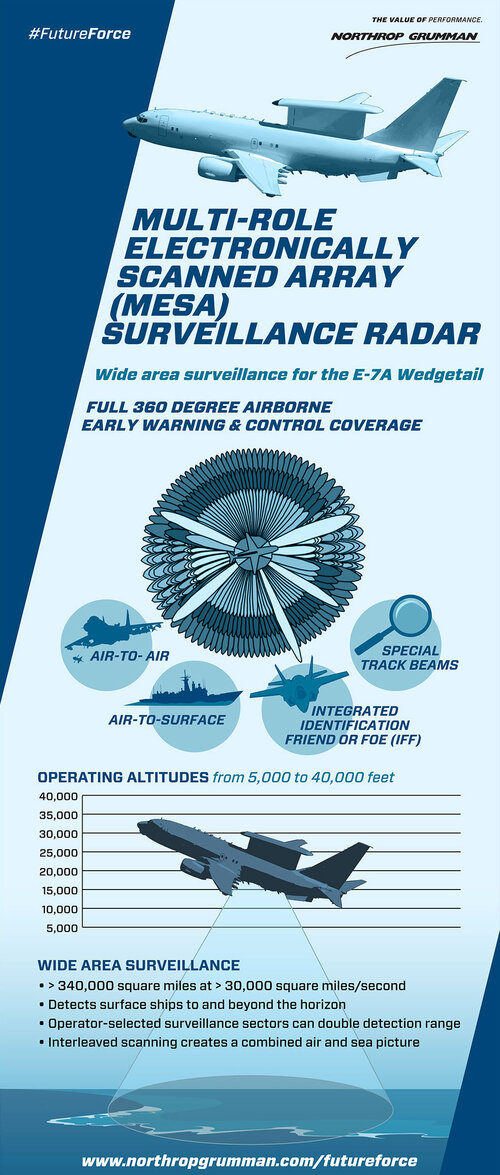

The Royal Australian Air Force selected Boeing in 1999 to design the E-7 under Project Wedgetail. Consequently, an E-7 procurement would represent a rare move by the Air Force to acquire a sophisticated weapon system designed to a foreign performance specification. But Gen. Mark Kelly, head of Air Combat Command, dismissed concerns about the scope of any changes that could be demanded by U.S. operators. Kelly noted that the E-7 is based on the Northrop Grumman Multi-Role Electronically Scanned Array, a “top-hat” array that provides instantaneous, 360-deg. coverage, and Boeing--designed mission systems. Kelly is confident that the E-7 technology, a product of U.S.-based contractors, meets the Air Force’s standards.

A U.S.-operated alternative to the E-7 exists in the Navy’s Northrop E-2D Advanced Hawkeye, which features a Lockheed Martin APY-9 array. But Kelly said the carrier-based E-2D is not a suitable replacement option for the E-3. The range provided by the E-2D radar may be adequate for the carrier battle group’s requirements, but it falls short of the standard required by the Air Force, Kelly said.

The acquisition of a new aircraft fleet for Airborne Moving Target Indication (AMTI) comes as the Air Force continues to evaluate the composition of its future fighter fleet. For two decades, the Lockheed F-35A served as the standalone replacement for all F-16s and A-10s, but that is no longer assumed. As an ongoing Fighter Roadmap study continues, the Air Force has already established that a certain number of F-16s and A-10s will remain in the fleet through the 2030s—even as Boeing F-15EXs replace aging F-15Cs and the Next-Generation Air Dominance program replaces the Lockheed F-22. With F-16s and A-10s assuming a long-term role in the Air Force fleet, the study will raise pressure on the service to adjust the 1,763-aircraft program of record for the F-35A downward.

However, a gap still exists in the fighter force structure for replacing about 600 F-16 Block 40/42/50/52 aircraft as they reach flight-hour limits within or beyond the 2030s. The so-called MR-X, a concept for a clean-sheet, low-end fighter design, is a candidate for replacing those F-16s, Kelly said. Other options may include new Lockheed F-16Vs or a light fighter version of the Boeing T-7A trainer.

“MR-X is basically an acknowledgment of [the fact that] we need affordable capacity,” Kelly said. The roughly 600 F-16s are “going to be our affordable capacity for years to come,” he continued. “Eventually though, like anything that’s metal, [if] you bend it enough times you [will] have to replace it. And that’s where the MR-X discussion and options start to come into play.”

In the near term, the Air Force is waiting for the F-35 Joint Program Office (JPO) to finalize the next major upgrade for the aircraft. The Lockheed fighter is due to receive the Technical Refresh-3 upgrade in fiscal 2023, which enables a series of sensor and electronic warfare upgrades that follow through to fiscal 2027. Now, the JPO is considering a major propulsion system upgrade to provide additional cooling and thermal management to cope with the aircraft’s more powerful electronics. Options include a major engine enhancement package for the Pratt & Whitney F135 or replacing the propulsion system with the Adaptive Engine Technology Program (AETP), which has funded the development of the GE Aviation AX100 and Pratt AX101.

Top Air Force officials had previously voiced concerns about the costs of an AETP program, but Kendall appears to be open to the idea. “The fuel savings and the thrust increase that we could get out of that have a lot of value,” he said.

The Air Force is in discussions with the Navy to apply the same engine to the F-35C fleet, Kendall added.

“I’m hoping we’ll be able to go forward together,” he said. “If we have to, we’ll look hard at the affordability of moving forward just as an Air Force program. Those advantages are substantial, and I’d like to be able to pursue it, if it’s affordable.”