You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

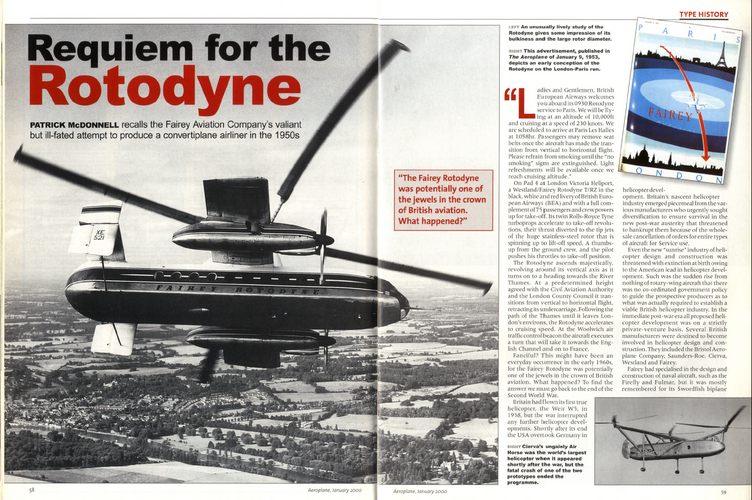

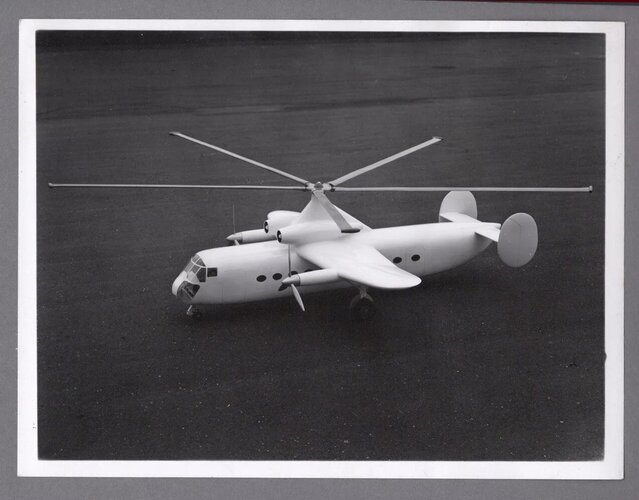

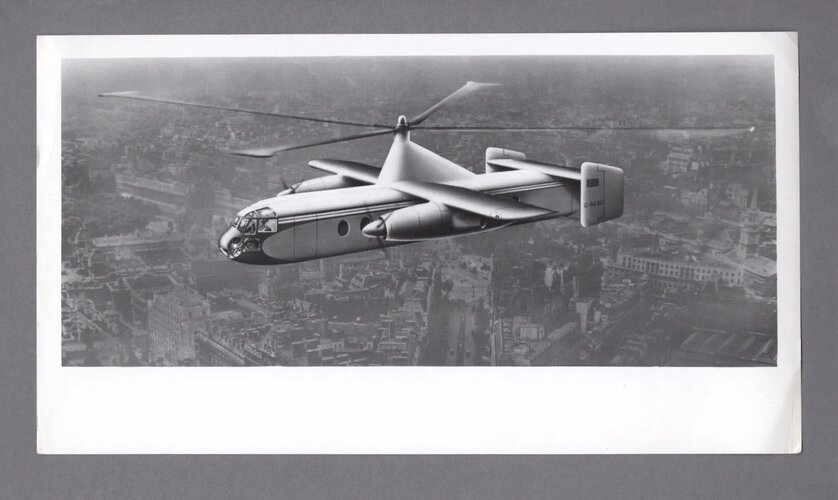

The Fairey Rotodyne

- Thread starter rocketeer

- Start date

- Joined

- 26 May 2006

- Messages

- 34,798

- Reaction score

- 15,680

From Air Pictorial 1961,

a 65-seat version.

From Wikipedia;

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

a 65-seat version.

From Wikipedia;

Fairey Rotodyne - Wikipedia

Attachments

- Joined

- 18 October 2006

- Messages

- 4,203

- Reaction score

- 4,880

It is sad that British politics and American industrial concerns were so caustic at the time. One does wonder where we might be if the VTOL platform had not been so repressed. I know some would argue that the most of the technological development happened for VTOL at the time, but that was not a threat to the aircraft industry that was fully invested in fixed wing commercial aircraft and infrastructure.

Last edited:

aonestudio

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 11 March 2018

- Messages

- 2,961

- Reaction score

- 7,471

- Joined

- 18 October 2006

- Messages

- 4,203

- Reaction score

- 4,880

But ... it has propellers. Propellers = 20th Century. Much of the traveling public think it antiquated. Unless the aircraft shows a significant financial cost decrease to the traveling public and the airline company it is unlikely it would be viable. What is its carbon footprint?

This is sad to me as I have always loved the Rotodyne.

This is sad to me as I have always loved the Rotodyne.

- Joined

- 1 April 2006

- Messages

- 11,360

- Reaction score

- 10,128

Attachments

southwestforests

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 28 June 2012

- Messages

- 744

- Reaction score

- 1,188

These may partly address that,why no Manufacturer to date has shown commercial interest in both the Civil and Military potential

Grounded Dreams: Fairey Rotodyne, The Hybrid Wish

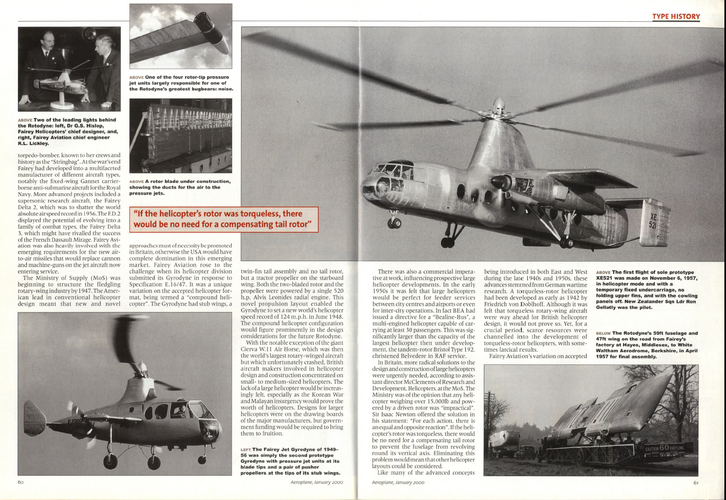

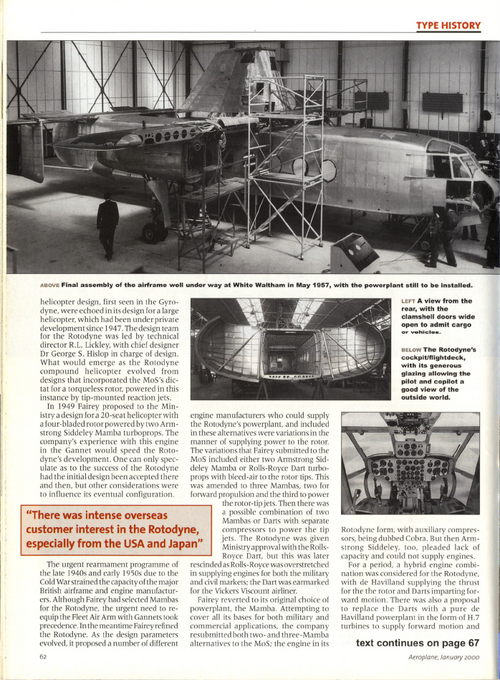

The Fairey Rotodyne stands as a testament to the ambitious vision and innovative prowess of Fairey Aviation, representing a pivotal moment in the history of aeronautical engineering. [...]

Despite all the promise, the Rotodyne project came to an abrupt halt in 1962. Several factors contributed to its downfall. One of the most significant issues was noise; the air jets used to power the rotor during takeoff and landing were incredibly loud—too loud for urban areas. Since the whole point of the Rotodyne was to operate between city centers, the noise problem became a dealbreaker for many potential buyers.

and

Why did the half-plane, half-helicopter not work?

The first helicopter flew 80 years ago, but it's never caught on as a mass mode of transport. But there was one brave British attempt.

www.bbc.com

But the talk never resulted in a regular service. Fairey was taken over by Westland in 1960 and continued the research, but there was a problem with noise from the jet tips on the rotor blades, which made it less practical to operate the Rotodyne in built-up areas.

Government monitors worked out that noise levels within 500ft from the pad during take-off and landing were "intolerable" and that those within 1,000ft (305m) of the Rotodyne in mid-flight were "unpleasantly noisy" - the same as hearing a raised voice from 2ft (60cm) away.

In 1958, Canadian company Okanagan Helicopters put in an order, but the Rotodyne was too loud for trips between Vancouver and the city of Victoria, 100km (62 miles) apart, and the service never started.

However ...

An even more important factor may have been, (bold highlighting done by me)

There were concerns that the helipad at Battersea, south London, which the Rotodyne was to use, was too far from the city centre. In March 1961, the New Scientist quoted one man as having taken less than half an hour to fly there by helicopter from Shoreham, West Sussex, but having taken another 35 minutes to get to his office in Regent Street by taxi.

Helipads could not be placed nearer business centres "for noise reasons or because of the high cost of land", the magazine said.

Similar threads

-

Fairey Tactical Strike Aircraft GOR.339 Project 75

- Started by Welshy42

- Replies: 12

-

-

-

-

F.155T the last minute submissions

- Started by zen

- Replies: 9