You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Submersible aircraft

- Thread starter Antonio

- Start date

regarding this april fool's joke, it must have been a pure coincidence for Flight to publish the 'fake' article on this day. and apart from that it doesn't say its a GD design, but the reader claims that it is his project for college qualification.

anyway, i made a query which so far went unheeded. can anyone give me the information?

anyway, i made a query which so far went unheeded. can anyone give me the information?

Matej

Multiuniversal creator

kenneth said:can anyone give any information about the following submersible aircraft:

M Evans design (picture 01.jpg on pg 1 of this topic);

Popadales airship;

Reid airship;

submersible plane (pic 2 on pg 1 of this topic);

thanks

...its difficult to give you the information mainly because I absolutely don't know, what you are asking for.

1. What is "M Evans design"? There is one picture named 01.jpg and in the post there is clearly written, that it was used in book from Jean Jacques Antier named Operation avion sous-marin

2. What is Popadales airship? The only word "popadales" in the whole forum is in your post so once again - what you are asking?

3. At least I don't know anyting further about Reid airship. Donald V. Reid built and tested his own flying submarine RFS-1 that is currently in Mid Atlantic Aviation Museum in Pensilvania. Who have access there, any other info is welcome. I tried it without success.

4. Which submersible plane?? There is nothing named "picture2.jpg" "2.jpg" or anything else. For the further reference it is much usefull to write... in "Reply no. XX" and in this post picture named "xxxx.jpg"

In case of what I wrote you shouldn't wonder that nobody answered.

Matej

Multiuniversal creator

Okay, it will help. If the photos are already uploaded on the forum, you don't need to attach them once again, just write the number of the reply (you can see it in the head of every post as "reply no. XX") and the full name of the picture, that belongs to this post and that you are referring to.

Thanks for making matters easier. what i need to know is:

from reply no 3: more information about the 'M Evans' submersible aircraft - what stage did it reach? drawings only? mock up? prototype?

from reply no 6: there is a picture titled Popadales Airship - anyone can give more information about that design?

from reply no 6: there is a picture titled Reid Airship - that is i think incorrect as that aircraft is something different from RFS-1. can you tell me what is it?

from reply no 8: anyone knows who designed these proposed aircraft shown in both pictures - the upper one seems similar to that shown in reply 6

thanks for your help.

from reply no 3: more information about the 'M Evans' submersible aircraft - what stage did it reach? drawings only? mock up? prototype?

from reply no 6: there is a picture titled Popadales Airship - anyone can give more information about that design?

from reply no 6: there is a picture titled Reid Airship - that is i think incorrect as that aircraft is something different from RFS-1. can you tell me what is it?

from reply no 8: anyone knows who designed these proposed aircraft shown in both pictures - the upper one seems similar to that shown in reply 6

thanks for your help.

M

McColm

Guest

Hi guys,

I know this isn't a new idea, as I have read that a university Professor has tested R/C model propeller aircraft in a tank. He came up with the suggestion that as long as the aircraft is watertight, the wings are streamlined and the propellers are moved to the right pitch. This theory this can work.

Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow!!

My ex has come up with the suggestion that air is a liquid.

Why would you fly underwater? For stealth, exploration, or tourism ASW or anti-ship attack. As long as you don't go too deep. You could travel faster than a boat or a submarine and no one would suspect you.

I haven't worked out if a jet could work under water, like a ski-jet?

I know this isn't a new idea, as I have read that a university Professor has tested R/C model propeller aircraft in a tank. He came up with the suggestion that as long as the aircraft is watertight, the wings are streamlined and the propellers are moved to the right pitch. This theory this can work.

Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow!!

My ex has come up with the suggestion that air is a liquid.

Why would you fly underwater? For stealth, exploration, or tourism ASW or anti-ship attack. As long as you don't go too deep. You could travel faster than a boat or a submarine and no one would suspect you.

I haven't worked out if a jet could work under water, like a ski-jet?

- Joined

- 18 March 2008

- Messages

- 3,529

- Reaction score

- 976

McColm said:My ex has come up with the suggestion that air is a liquid.

Your ex is Evangelista Torricelli? Apart from the apparent alternative lifestyle choice that would make you almost 400 years old...

Earth's air is a fluid like sea water but the sea is a far more dense fluid than air. But the same principals apply except you don't need to generate lift to move through water but you don't have a ready oxidant for operating some types of engines. There are of course a range of highly complex engineering problems to make something that can operate underwater but also be light enough to fly.

The reason there has been some interest from time to time in building an underwater amphibian aircraft is there are a few tactical benefits. These can be divided into two areas: basing and operational. Having an underwater amphibian aircraft provides for a secure basing environment underwater and potentially even amphibian operation in high sea states if the vehicle can transition directly from submarine to flying mode (a common concept in sci-fi though very unlikely due to the high underwater speeds needed of over 100 knots). Operational needs include sailing underwater for stealth and to attack targets (like submarines).

PS a jetski uses a pump jet to operate which is very different to a turbojet on an aircraft.

Matej

Multiuniversal creator

McColm said:Why would you fly underwater?

This is the general question. The general answer is that it is good to have the devices that can produce the lift, because than you can move in the water smooth and fuel effectively. This is why the modern fast submarines (pictures attached) look like the aeroplanes. But only almost aeroplanes, since they cant fly.

The need to have the device, that is able to submerse, fly in the air and also fly in the water comes from the military and the keyword is (was) unexpected attack. This was one of the ideas, how to come near to the target unnoticed and attack it. For the civil purposes, the difficulties to make the vehicle that is able to fly in air and in the water with 800x (?) higher density are big enough to stop any real development.

McColm said:I haven't worked out if a jet could work under water, like a ski-jet?

If you mean jet engine, no, it cant. The only way is to make it water resistant and than power the compressors by electric motor, supplied by the batteries. But there are many other solutions that are much effective, like the screw-propeller. This is also the reason, why almost all submersible aircraft proposals have two independent propulsion systems - one to work in air and one to work in the water.

Attachments

M

McColm

Guest

Many thanks to Abraham Gubler and Matej.

The closet I've got to seeing a flying submarine was in the back of a C-5 Galaxy transport plane this was on the way with a DSRV. I can't tell you where we were, but the DSRV was very impressive when it was launched from the back end of the C-5 whilst in flight.

Deep Submergence Rescue Vehicle.

Propulsion for the submersible aircraft could either come from a solid-fuel rocket or be nuclear powered. The former Soviet Navy used to deploy their submarines from the pens in the north to the sunnier climate of Cuba. Certain submarines could achieve up to 50 knots. Which is slightly faster than the fastest crossing by power boat across the Atlantic.

The closet I've got to seeing a flying submarine was in the back of a C-5 Galaxy transport plane this was on the way with a DSRV. I can't tell you where we were, but the DSRV was very impressive when it was launched from the back end of the C-5 whilst in flight.

Deep Submergence Rescue Vehicle.

Propulsion for the submersible aircraft could either come from a solid-fuel rocket or be nuclear powered. The former Soviet Navy used to deploy their submarines from the pens in the north to the sunnier climate of Cuba. Certain submarines could achieve up to 50 knots. Which is slightly faster than the fastest crossing by power boat across the Atlantic.

- Joined

- 1 April 2006

- Messages

- 11,375

- Reaction score

- 10,203

http://translate.google.com/translate?u=http://hkom.ru/inspector-s/&sl=ru&tl=en&hl=en&ie=UTF-8

http://www.secretprojects.co.uk/forum/index.php/topic,6847.msg58518.html#msg58518

it's not submersible chopper

it's underwater rotorcraft

http://www.secretprojects.co.uk/forum/index.php/topic,6847.msg58518.html#msg58518

it's not submersible chopper

it's underwater rotorcraft

OM

ACCESS: Top Secret

AeroFranz said:Thanks for the clarification! Google translate is a pretty cool tool, but I'm afraid it has a long way to go before adequately translating technical text

....And speaking from experience, transliterating technical Russian can be a royal pain in the ass. :'(

Gannet

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 18 March 2008

- Messages

- 43

- Reaction score

- 12

McColm said:Why would you fly underwater? For stealth, exploration, or tourism ASW or anti-ship attack.

See page 5 of 19 for Motivation and page 6 of 19 for Mission Profile

http://www.darpa.mil/sto/solicitations/BAA09-06/files/Proposers_Day_Presentation.pdf

The above link also has charts addressing the five Technical Challenges

Gannet

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 18 March 2008

- Messages

- 43

- Reaction score

- 12

Found this recent (Feb 2009) interesting paper which discusses both the syfy and history of submersible aircraft and other similar crafts

http://www.verlab.dcc.ufmg.br/_media/publicacoes/drews09survey.pdf?cache=cache

Enjoy

http://www.verlab.dcc.ufmg.br/_media/publicacoes/drews09survey.pdf?cache=cache

Enjoy

Matej

Multiuniversal creator

Lauge

ACCESS: Secret

- Joined

- 30 January 2008

- Messages

- 434

- Reaction score

- 55

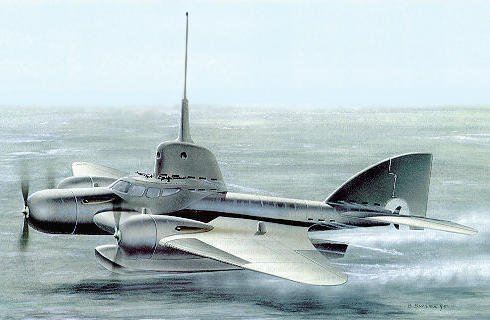

Matej said:Magnificent Ushakov LPL rendering from Precise3DModeling.com

I believe I've already mentioned this in another post quite a while ago, but here's Aircraft Recognition 101: "If it's weird, it's English, if it's ugly, it's French, if it's weird and ugly, it's Russian".

That aside, how can you NOT love that ? It's got exactly the right kind of "steampunk meets League of Extraordinary Gentlemen" look.

Regards & all,

Thomas L. Nielsen

Denmark

- Joined

- 25 June 2009

- Messages

- 14,749

- Reaction score

- 6,113

A very interesting video animation of the Russian flying submarine aircraft (LPL) project.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xxyf3O_SyYQ

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xxyf3O_SyYQ

Gannet

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 18 March 2008

- Messages

- 43

- Reaction score

- 12

Found this article http://www.subaviators.com/Portals/0/News/DIVER_JUNE_2009_Flying%20Subs.pdfthat discusses submersibles that fly underwater using dynamic lift. It also mentions submersible aircraft "Joseph Hardo’s ‘Submarine Flying Boat’ of 1922, or Longobardi’s 1918 submarine-cum-aircraft described elegantly as a “Combination Vehicle” It also shows some unreadable thumbnails of the patent sketches. While doing an internet search on Longobardi he also developed concepts for the flying car. I think he was trying to develop Jules Verne's Terror from "Master of the World".

When reading a recent patent by Graham Hawkes http://www.freepatentsonline.com/7131389.pdfon submersibles it cites Ardo in 1922 not Hardo which I believe is incorrect.

When reading a recent patent by Graham Hawkes http://www.freepatentsonline.com/7131389.pdfon submersibles it cites Ardo in 1922 not Hardo which I believe is incorrect.

Matej

Multiuniversal creator

boxkite said:From a 1965 episode of I've Got A Secret

Is anybody lucky to save this video? It is not online anymore...

Avimimus

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 15 December 2007

- Messages

- 2,426

- Reaction score

- 907

Doesn't the video misrepresent the LPL? If I recall correctly, the major advantage it was expected to have was the ability to travel quickly to a patrol area, attack and then return to base to be loaded with fresh torpedoes and sent out again. In this way several attacks could be made during the time it would take a conventional submarine to cover the distance between a patrol area and its base.

I find the idea of the LPL being flown undetected into an enemy harbour and then diving, attempting to manoeuvre in narrow waters, firing its torpedoes at point blank range and then surfacing and flying away a little bit unbelievable.

I find the idea of the LPL being flown undetected into an enemy harbour and then diving, attempting to manoeuvre in narrow waters, firing its torpedoes at point blank range and then surfacing and flying away a little bit unbelievable.

hesham said:Hi,

http://www.vtol.boom.ru/

thanks for link !

it's very interesting !

Matej

Multiuniversal creator

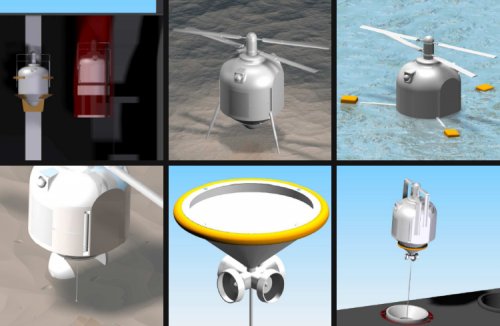

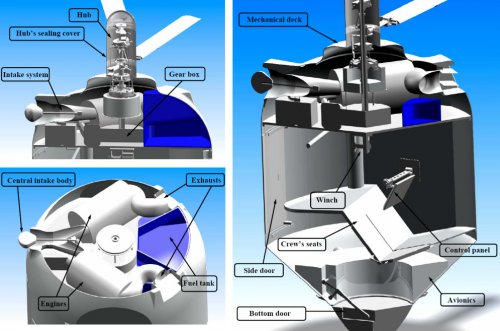

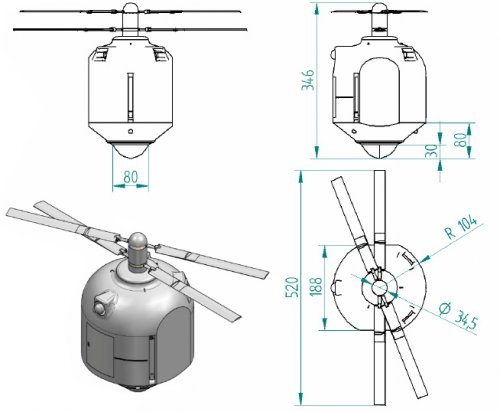

You only need to search enough and you will find everything. Now we have at least partially serious effort to design the submersible chopper. "Partially serious" mainly because it is the students project, however the one, that won the first prize in the undergraduate category of the 24th annual student design competition hosted by the American Helicopter Society and sponsored by Sikorsky. The winning concept, designated "Waterspout", is the brainchild of a team of students from the Faculty of Aerospace Engineering at the Technion - Israel Institute of Technology and Pennsylvania State University.

Competition requirements called for design of a UAV that will deploy from the submarine while at a periscope depth of 15 meters, rise to sea level, be able to float and take off in moderate conditions and then fly 260km. The system would be able to both deploy and retrieve personnel and return them to the submerged submarine. The whole paper is available at vtol.org site:

http://www.vtol.org/pdf/2007PSU_TechnionUndergrad.pdf

Competition requirements called for design of a UAV that will deploy from the submarine while at a periscope depth of 15 meters, rise to sea level, be able to float and take off in moderate conditions and then fly 260km. The system would be able to both deploy and retrieve personnel and return them to the submerged submarine. The whole paper is available at vtol.org site:

http://www.vtol.org/pdf/2007PSU_TechnionUndergrad.pdf

Attachments

Gannet

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 18 March 2008

- Messages

- 43

- Reaction score

- 12

Found this article today, did not see it in any of the previous posts. It is by Norman Polmar. He has alot info on the Convair/General Dynamics Subplane in this article

http://www.military.com/forums/0,15240,179699,00.html?wh=wh

http://www.military.com/forums/0,15240,179699,00.html?wh=wh

Fascinating, thanks!Matej said:You only need to search enough and you will find everything. Now we have at least partially serious effort to design the submersible chopper. "Partially serious" mainly because it is the students project, however the one, that won the first prize in the undergraduate category of the 24th annual student design competition hosted by the American Helicopter Society and sponsored by Sikorsky. The winning concept, designated "Waterspout", is the brainchild of a team of students from the Faculty of Aerospace Engineering at the Technion - Israel Institute of Technology and Pennsylvania State University.

Competition requirements called for design of a UAV that will deploy from the submarine while at a periscope depth of 15 meters, rise to sea level, be able to float and take off in moderate conditions and then fly 260km. The system would be able to both deploy and retrieve personnel and return them to the submerged submarine. The whole paper is available at vtol.org site:

http://www.vtol.org/pdf/2007PSU_TechnionUndergrad.pdf

XP67_Moonbat

ACCESS: Top Secret

- Joined

- 16 January 2008

- Messages

- 2,271

- Reaction score

- 541

http://www.darkroastedblend.com/2007/08/flying-submarines.html

- Joined

- 26 May 2006

- Messages

- 34,873

- Reaction score

- 15,733

Gannet said:Found this article http://www.subaviators.com/Portals/0/News/DIVER_JUNE_2009_Flying%20Subs.pdfthat discusses submersibles that fly underwater using dynamic lift. It also mentions submersible aircraft "Joseph Hardo’s ‘Submarine Flying Boat’ of 1922, or Longobardi’s 1918 submarine-cum-aircraft described elegantly as a “Combination Vehicle” It also shows some unreadable thumbnails of the patent sketches. While doing an internet search on Longobardi he also developed concepts for the flying car. I think he was trying to develop Jules Verne's Terror from "Master of the World".

When reading a recent patent by Graham Hawkes http://www.freepatentsonline.com/7131389.pdfon submersibles it cites Ardo in 1922 not Hardo which I believe is incorrect.

Hi,

http://www.theengineer.co.uk/news/deep-flight/300709.article

EDIT: I've moved this post and the related pictures to the Naval Projects section, as actually these

are submarines and could lead to confusion here.

Jemiba

http://www.secretprojects.co.uk/forum/index.php/topic,11934.msg115557.html#msg115557

- Joined

- 26 May 2006

- Messages

- 34,873

- Reaction score

- 15,733

pometablava said:From the superb book (lots of unbuilt projects): Cold War Submarines by Norman Polmar and KJ Moore. Brassey's ISBN: 1-57488-594-4

This is the only submersible aircraft I have drawings, the Convair "submersible seaplane" from 1964. It was cancelled in 1966.

I know that Dassault also developed a "submersible seaplane" but it was not a sub-hunter as that Convair's design. Dassault vehicle was a shuttle to link submarine facilities either civil or military. Sub-cities never materialized so the submersible seaplane remained on the drawing board. I'll try to draw what I remember from that pic I saw when I was younger and post it here.

Cheers

Antonio

Hi,

a model for Convair flying submarine (submersible) project.

http://www.flickr.com/photos/tom-margie/3278721779/

Attachments

- Joined

- 26 October 2010

- Messages

- 152

- Reaction score

- 26

The wing of the cormorant didn't morph - it just folded.

http://www.lockheedmartin.com/how/stories/cormorant.html

This was the LM morphing wing:

http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/1427182/posts

http://www.popsci.com/military-aviation-space/article/2005-07/bend-it-big-bird

http://www.lockheedmartin.com/how/stories/cormorant.html

This was the LM morphing wing:

http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/1427182/posts

http://www.popsci.com/military-aviation-space/article/2005-07/bend-it-big-bird

- Joined

- 25 June 2009

- Messages

- 14,749

- Reaction score

- 6,113

InvisibleDefender said:The wing of the cormorant didn't morph - it just folded.

http://www.lockheedmartin.com/how/stories/cormorant.html

This was the LM morphing wing:

http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/1427182/posts

http://www.popsci.com/military-aviation-space/article/2005-07/bend-it-big-bird

Thanks for clarifying this.

I wrongly assumed that Cormorant morphing wing were one and the same project. :-[

Matej

Multiuniversal creator

hesham said:Hi,

a model for Convair flying submarine (submersible) project.

http://www.flickr.com/photos/tom-margie/3278721779/

This is not from Convair, this is the imagination/fantasy from the Popular Mechanics, how should the submersible aircraft looks like. And someone made the model of it.

- Joined

- 26 October 2010

- Messages

- 152

- Reaction score

- 26

maybe not ... but I have no idea...

"In 1964, Convair proposed a radical submersible aircraft to the US Navy powered by turbojets and pumpjets."

and

"Soviet designer B.P. Ushakov designed this submersible aircraft, the LPL, which included a submarine like conning tower and a long periscope."

"In 1964, Convair proposed a radical submersible aircraft to the US Navy powered by turbojets and pumpjets."

and

"Soviet designer B.P. Ushakov designed this submersible aircraft, the LPL, which included a submarine like conning tower and a long periscope."

Attachments

- Joined

- 26 October 2010

- Messages

- 152

- Reaction score

- 26

Sounds real to me....

BY NORMAN POLMAR

The Navy's Bureau of Naval Weapons -- at the time responsible for aircraft development -- awarding a contract to Convair in 1964 to examine the feasibility of a "submersible flying boat," which was being called the "sub-plane" by those involved with the project. The Convair study determined that such a craft was "feasible, practical and well within the state of the art."

The Bureau of Naval Weapons specified a set of design goals:

air cruise speed 150 -- 225 mph

air cruise altitude 1,500 -- 2,500 feet

air cruise radius 300 -- 500 n.miles

maximum gross takeoff < 30,000 lb

submerged speed 5 -- 10 knots

submerged depth 25 -- 75 feet

submerged range 40 -- 50 n.miles

submerged endurance 4 -- 10 hours

payload 500 -- 1,500 lb

takeoff and land in State 2 seas

Several firms responded to a Navy request and a contract was awarded to Convair to develop the craft. The flying boat, which would alight and takeoff using retractable hydro-skis, would be propelled by three engines -- two turbojets and one turbofan, the former for use in takeoff and the latter for long-endurance cruise flight. Among the more difficult challenges of the design was the necessity of removing air from the engines and the partially full fuel tank to reduce buoyancy for submerging. Convair engineers proposed opening the bottom of the fuel tank to the sea, using a rubber diaphragm to separate the fluids and using the engines to hold the displaced fuel.

To submerge, the pilot would cut off fuel to the engines, spin them with their starter motors for a moment or two to cool the metal, close butterfly valves at each end of the nacelles, and open the sea valve at the bottom of the fuel tank. As the seaplane submerged, water would rise up into the fuel tank beneath the rubber membrane, pushing the fuel up into the engine nacelles. Upon surfacing, the fuel would flow back down into the tank. The only impact on the engines would be a cloud of soot when the engines were started.

When the engines were started their thrust would raise the plane up onto its skis, enabling the hull, wings, and tail surfaces to drain. The transition time from surfacing to takeoff was estimated to be two or three minutes, including extending the wings, which would fold or retract for submergence. Only the cockpit and avionics systems were to be enclosed in pressure-resistant structures. The rest of the aircraft would be "free-flooding." In an emergency the crew capsule would be ejected from the aircraft to descend by parachute when in flight, or released and float to the surface when underwater. In either situation the buoyant, enclosed capsule would serve as a life raft.

The craft would have a two-man crew and could carry mines, torpedoes or, under certain conditions, agents to be landed or taken off enemy territory.

The Navy Department approved development of the craft, with models subsequently being tested in towing tanks and wind tunnels. The results were most promising. But in 1966 Senator Allen Ellender, of the Senate's Committee on Armed Services, savagely attacked the project. His ridicule and sarcasm forced the Navy to cancel a project that held promise for a highly interesting "submarine." Although the utility of the craft was questioned, from a design viewpoint it was both challenging and highly innovative.

http://www.military.com/forums/0,15240,179699,00.html

BY NORMAN POLMAR

The Navy's Bureau of Naval Weapons -- at the time responsible for aircraft development -- awarding a contract to Convair in 1964 to examine the feasibility of a "submersible flying boat," which was being called the "sub-plane" by those involved with the project. The Convair study determined that such a craft was "feasible, practical and well within the state of the art."

The Bureau of Naval Weapons specified a set of design goals:

air cruise speed 150 -- 225 mph

air cruise altitude 1,500 -- 2,500 feet

air cruise radius 300 -- 500 n.miles

maximum gross takeoff < 30,000 lb

submerged speed 5 -- 10 knots

submerged depth 25 -- 75 feet

submerged range 40 -- 50 n.miles

submerged endurance 4 -- 10 hours

payload 500 -- 1,500 lb

takeoff and land in State 2 seas

Several firms responded to a Navy request and a contract was awarded to Convair to develop the craft. The flying boat, which would alight and takeoff using retractable hydro-skis, would be propelled by three engines -- two turbojets and one turbofan, the former for use in takeoff and the latter for long-endurance cruise flight. Among the more difficult challenges of the design was the necessity of removing air from the engines and the partially full fuel tank to reduce buoyancy for submerging. Convair engineers proposed opening the bottom of the fuel tank to the sea, using a rubber diaphragm to separate the fluids and using the engines to hold the displaced fuel.

To submerge, the pilot would cut off fuel to the engines, spin them with their starter motors for a moment or two to cool the metal, close butterfly valves at each end of the nacelles, and open the sea valve at the bottom of the fuel tank. As the seaplane submerged, water would rise up into the fuel tank beneath the rubber membrane, pushing the fuel up into the engine nacelles. Upon surfacing, the fuel would flow back down into the tank. The only impact on the engines would be a cloud of soot when the engines were started.

When the engines were started their thrust would raise the plane up onto its skis, enabling the hull, wings, and tail surfaces to drain. The transition time from surfacing to takeoff was estimated to be two or three minutes, including extending the wings, which would fold or retract for submergence. Only the cockpit and avionics systems were to be enclosed in pressure-resistant structures. The rest of the aircraft would be "free-flooding." In an emergency the crew capsule would be ejected from the aircraft to descend by parachute when in flight, or released and float to the surface when underwater. In either situation the buoyant, enclosed capsule would serve as a life raft.

The craft would have a two-man crew and could carry mines, torpedoes or, under certain conditions, agents to be landed or taken off enemy territory.

The Navy Department approved development of the craft, with models subsequently being tested in towing tanks and wind tunnels. The results were most promising. But in 1966 Senator Allen Ellender, of the Senate's Committee on Armed Services, savagely attacked the project. His ridicule and sarcasm forced the Navy to cancel a project that held promise for a highly interesting "submarine." Although the utility of the craft was questioned, from a design viewpoint it was both challenging and highly innovative.

http://www.military.com/forums/0,15240,179699,00.html

- Joined

- 11 March 2006

- Messages

- 8,624

- Reaction score

- 3,792

"This is not from Convair, this is the imagination/fantasy from the Popular Mechanics, how should the submersible aircraft looks like. And someone made the model of it."

Ah, then I wasn't wrong, when I thought, that this model looks like a kit bashed Lockheed Ventura !

Ah, then I wasn't wrong, when I thought, that this model looks like a kit bashed Lockheed Ventura !

Matej

Multiuniversal creator

Well, not Popular mechanics but Air Progress: http://www.secretprojects.co.uk/forum/index.php/topic,703.msg5408.html#msg5408 We should (everybody) read the topic once again from the beginning.

- Joined

- 25 June 2009

- Messages

- 14,749

- Reaction score

- 6,113

Matej said:Well, not Popular mechanics but Air Progress: http://www.secretprojects.co.uk/forum/index.php/topic,703.msg5408.html#msg5408 We should (everybody) read the topic once again from the beginning.

Is this to say that Scott Lowther also got it wrong?!? ???

http://www.up-ship.com/eAPR/ev2n6.htm

Similar threads

-

All American Company Aircraft Projects

- Started by hesham

- Replies: 18

-

-

Unterwasser-Tauchfahrzeug (UT-Kampfwagen) submersible tank

- Started by Wurger

- Replies: 15

-

-

Why are there no WIG Type Unmanned Surface Vehicles

- Started by Gannet

- Replies: 10

![IMG_1001 [1024x768].JPG](/data/attachments/28/28074-22f9ce631a6dba2cae350996de454aa0.jpg)