You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

RATTLRS

- Thread starter Hanse

- Start date

"It's More Powerful Than A Blackbird (And It Fits In The Trunk)"

October 1, 2009

Source:

http://www.popularmechanics.com/science/2875216

October 1, 2009

Source:

http://www.popularmechanics.com/science/2875216

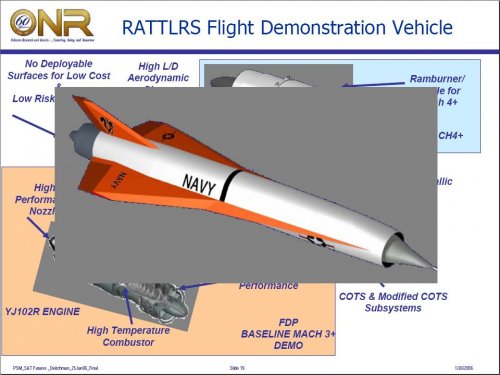

Pumping out six times the specific impulse of an SR-71’s afterburning J-58 engine, the YJ102R might be the most powerful turbojet on the planet—at least by weight. It’s barely bigger than two breadboxes. Yet the Liberty Works / Rolls Royce-designed powerplant will push a new generation of cruise missiles, the Lockheed Martin Skunk Works-built Revolutionary Approach To Time-critical Long Range Strike (RATTLRS), past Mach 3.

Lockheed Martin and the Office of Naval Research (ONR, the DoD office that sponsored the missile’s development) invited Popular Mechanics to take a look at a full-scale model of RATTLRS, on display on the hanger deck of the USS Kearsarge. It’s name might be awkward, but RATTLRS is as sleek as they come. Literally—the missile’s translating nose spike and highly swept wings look almost identical to the SR-71’s nacelle. “It’s almost as if it’s heritage,” ONR program manager Lawrence Ash says.

It might look heritage, but it’s pretty clear there’s some serious innovation inside the diminutive missile’s 21-foot-long airframe. For one, it uses no afterburner, yet is powerful enough to accelerate through the sound barrier while in a steep climb—an impossible feat until now. How does a single-spool YJ102R—with a compressor stage shorter than a foot long—generate that much power? That’s, um, half classified and half industry secret. But, says Rolls Royce’s Wayne Moni, “the high air temperature makes that power possible.”

And high temperature means high pressure, which brings us back to the nose spike. The SR-71’s engine’s biggest innovation was it’s spike, which moved forward and aft, changing the geometry of the intake to absorb the high-mach shockwave and slow the intake air to sub-sonic speeds. The Blackbird’s engine used a sophisticated bleed air vents in the spike that sucked in air, bypassing the compressor and lowering intake pressure. This air was—depending on the Mach number, either bled into the atmosphere or reinjected into the engine farther down the line.

Nobody will say whether there are bleed vents on the spike, but there are pretty obvious bleed vents along the forward quarter of the missile, which Skunk Works deputy program manager Barry Brown confirmed were bleed vents to lower pressure. It’s likely that the airspike’s translation alters how much intake air flows out of those vents, closing them off at lower Mach numbers to create pressure, and opening them in the Mach 3+ regime to keep the air volume from overwhelming the compressor.

Either way, it doesn’t seem like that air is reinjected anywhere else along the line, although Bob Duge of Rolls Royce tells me future versions will employ additional ram air in the combustor. “That will get us closer to hypersonic speeds,” he says.

What is clear is that the lack of a JP-10 sucking afterburner means huge savings in fuel economy, greatly lowering weight and increasing range. How far, exactly, is also classified, but Brown says the missiles first flight next year is planned at 500 nautical miles.

So what, exactly, is this revolutionary new missile going to deliver, and to whom? That, also, is classified, although the missile’s unclassified information card features a graphic of a bunker-buster type missile along with a cluster bomb. And although he does confirm that the missile’s purpose includes the Global War on Terror, ONR’s Ash won’t divulge other target sets. “Let’s just say,” he tells me, “that RATTLRS is designed to hit targets with great precision within minutes of a decision to strike.”

There’s just one problem: A customer. Although the missile is designed for placement on everything from a B-52 to the Joint Strike Fighter to a destroyer to a submarine, Congress has yet to express interest in the missile.

But even if the RATTLRS prototype is a one-off, if it really delivers the combination of reliability, affordability and extreme speed promised by the design team, the technology will eventually mature. Who doesn’t need an engine that’s no bigger than a six cylinder—and is rated to Mach 3? —Benjamin Chertoff

RATTLRS is on display to the public through Tuesday, on board the USS Kearsarge, Pier 88 in Manhattan.

Was the Lockheed Martin RATTLRS project an answer to the Indo-Russian BrahMos?

Triton said:Was the Lockheed Martin RATTLRS project an answer to the Indo-Russian BrahMos?

No. Completely different animal.

http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/munitions/rattlrs.htm

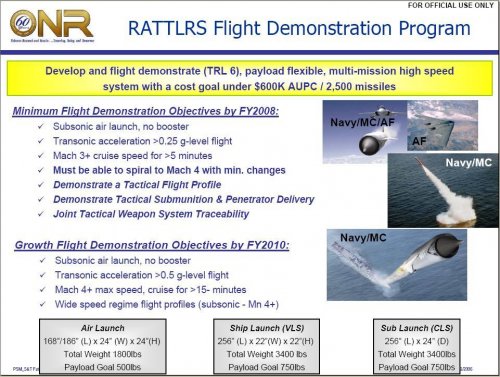

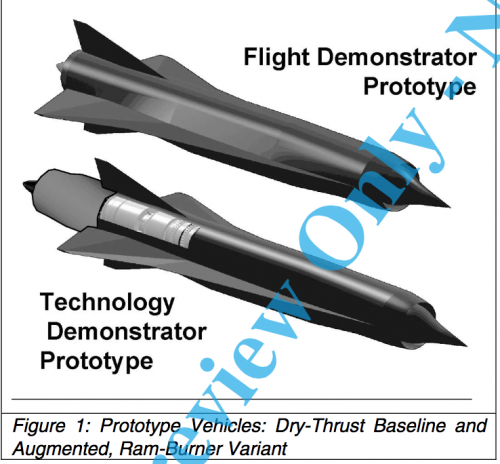

The flight demonstration vehicle of interest to the RATTLRS project is of a size, weight and configuration that has potential to develop into a tactical weapon system. The flight demonstrator vehicle must have the following attributes:

It is desirable that the flight demonstration project allow for growth opportunities (via RATTLRS TDP) for the design in areas such as:

The flight demonstration vehicle shall have a size, weight and configuration that has the potential to be developed into a tactical weapon system. Examples of the potential tactical weapons include (1) an air-launched (compatible with the F/A-18 E/F, F-22, and/or Joint Strike Fighter as a launch platform) medium range weapon with a maximum vehicle weight of 1800 lbs including 500 lbs payload or (2) a ship-launched/sub-launched Vertical Launch System (VLS) compatible long range weapon with a maximum weight of 3400 lbs including 750 lbs payload (includes vehicle and any booster required for VLS launch), or one vehicle compatible with multiple launch options if trade studies indicate an advantage to such a configuration. The higher weight would include the booster required to launch the missile from a vertical tube.

"As of May 2009 plans called for completing the RATTLRS flight test program by the end of 2009. [as of early 2010 this flight seems not to have happened]"

bring_it_on

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 4 July 2013

- Messages

- 3,623

- Reaction score

- 3,693

- Joined

- 21 April 2009

- Messages

- 13,713

- Reaction score

- 7,588

bring_it_on said:RATTLS Sled testing

Do you have the sled test 'after' picture? Those are more satisfying so to speak

bring_it_on

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 4 July 2013

- Messages

- 3,623

- Reaction score

- 3,693

bobbymike said:bring_it_on said:RATTLS Sled testing

Do you have the sled test 'after' picture? Those are more satisfying so to speak

I wish

This is what I have -

https://www.scribd.com/doc/260217166/RATTLRS-Sled-Tests-Meet-With-Success

Some others

https://www.scribd.com/doc/260173276/In-Brief-RATTLRS-Warhead-Tested?secret_password=lqHxnvonPvaIOrY925xB

https://www.scribd.com/doc/260173275/Skunk-Works-Completes-Structural-Testing-of-RATTLRS?secret_password=w1uNr3fxroqgKeDHjsO8

- Joined

- 21 April 2009

- Messages

- 13,713

- Reaction score

- 7,588

Although not RATTLRS (and off-topic a little) this is a personal favorite of mine, a M8.5 sled test (world record) I think sferrin told me on another thread this was MDA test for hit to kill warhead?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L5bPu58fSc0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L5bPu58fSc0

bring_it_on

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 4 July 2013

- Messages

- 3,623

- Reaction score

- 3,693

- Joined

- 6 August 2007

- Messages

- 3,858

- Reaction score

- 5,784

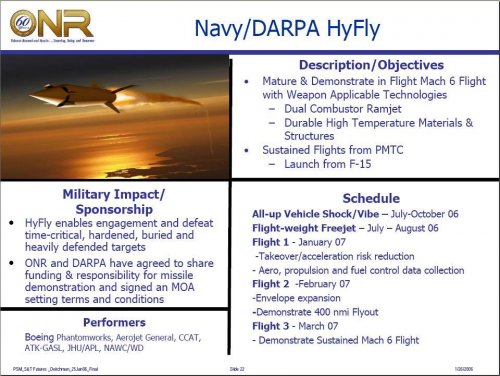

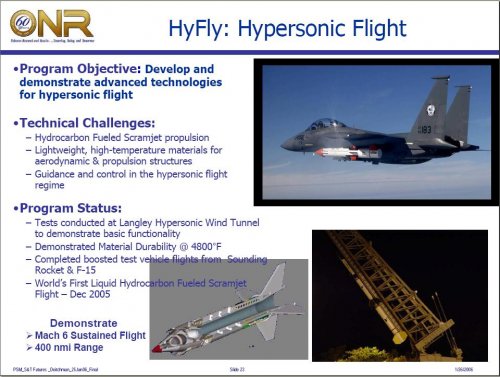

I'd have swore I posted them before. Stumbled upon them years ago when looking up a company that makes a XXXXX part. edit: Yep, most of them on the previous page. Somewhere I have pics of the *casting* that was the HyFly fuselage.Photos of the flight hardware.

- Joined

- 6 August 2007

- Messages

- 3,858

- Reaction score

- 5,784

I'd have swore I posted them before. Stumbled upon them years ago when looking up a company that makes a XXXXX part. edit: Yep, most of them on the previous page. Somewhere I have pics of the *casting* that was the HyFly fuselage.

They had disappeared after the company was acquired. I am very certain I have seen a photo of the parts above assembled into a hear complete flight article (not the mockup) but have been unable to locate it.

Scott Kenny

ACCESS: USAP

- Joined

- 15 May 2023

- Messages

- 11,233

- Reaction score

- 13,636

Amazing how much RATTLRS looks like a D-21...

The real amazing thing is that it's just part of a litany of missed opportunities to get high supersonic/low hypersonic weapons into the arsenal over the years.

That's the thing I don't get about the US DOD and their supersonic/hypersonic missile programmes, it's start/stop, start/stop, start/stop, start/stop, start/stop, and so on. They will never get anywhere if they keep up this idiotic developmental nonsense.

Similar threads

-

nianet.org - Hypersonic Flight Program Presentations

- Started by DSE

- Replies: 1

-

-

XM1208/XM1180 C-DAEM DPICM replacement and Anti-Armor

- Started by FlameCxbra

- Replies: 2

-

-