- Joined

- 27 December 2005

- Messages

- 17,117

- Reaction score

- 22,915

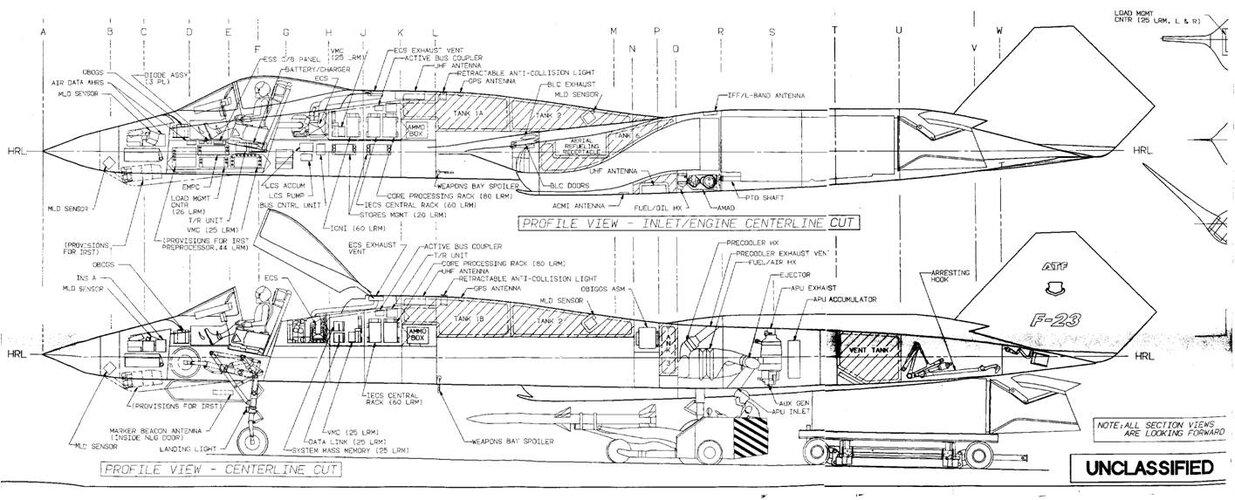

Its the same image as I linked just a few posts ago as yf23-4.png.

Reading through this thread again, I think some of the early takes require some corrections in light of more recent information.Many thaks to Flaterick to pointing out my patent research thing. I would not have said it myself.

Still elmayerle had a very good in Reply #21 . YF-23 design allowed not only aft and fore movement of the Bays but also increase in depth. There are no engines or airducs on top of the bay, only fuel and minor systems..

Looking at the F-23A as an aircraft designer I would say: yes its longer but since when lengthening the airplane is more risky than making it shorter, because the F-22A is indeed shorter and thinner in its middle section where you have weapons, fuel, air intakes, gun magazine. Packing the same stuff in less space is more riskier to me. Also lets not forget that F-22A had completely redesigned main weapons bay doors.

Now if we recall some of the problems the F-22 design went trough.

1. Overheating rear fuselage in Supercruise. Compare the rear of YF-22 and F-22A.How thinner it is on the production model. The F-23 with widely spaced engine blocks would not have had the problem of overheating.

2. Shockwaves in the Engine inlets requiring a strengthen forward fuselage after Raptor 01. No wonder, the air intakes on the A model are obviously shorted than the prototype. The F-23A has inlets way more optimized to handle supersonic airflow and the adoption of the concept by the F-35 only proves it.

3. F-22 was always criticized by not being able to carry big bombs. The latest FB-22 proposal features bulged up main weapon doors so it can house the 2000lb JDAM, yet the fuselage is the same is used with no lengthening to reduce cost. The YF-23 had a deeper bay and would have no problem fitting the 2000lb JDAM.

4. The 1994 redesign due to signature problem, costing probably a year delay in the F-22 program. Looking at the F-22A and you ca see it borrowed a lot of the Black Widow features: he shape of the nose, the way the aircraft brakes, the probes measuring AoA on the side of the radome, the minimum number of edges every panel, the topside of the engines, the clipping of the all moving tails. Yet the F-23A design features stealth/performance blending from the next level, like the inlet cone design.

5. Weight. The inability for the F-22 design to meet it weigh target is attributed to the failure of its designers to meat their goal of 50% Composites in the Airframe(2 as well). From the news article flaterick send me it is clear that the F-22A proposal in material is similar to the YF-23 design (one step behind). Also the F-23A featues not only 50% composits but BMI termosets account for a higher percentage out of that than the same BMI termoset do out of the total composits used on the F-22A, which are only 24%.(Flight International March 1997)

To me the F-23A would have had easier time meeting its weight target. As far as risk goes the change between Lockheeds 1985 winning design and the YF-22 tells me all I need to know about confidence in concept and the ability of USAF to choose their aeroplane based on their flying qualities. Same with the Rockwell F-X submition looking so much like SU-27. I hope the PAKFA does not turn out the be looking like the YF-23. I am going to be massively upset with defense secretary Rice, who chose the F-22

Regards, to all

P.S. I hope you are all enjoyng this discusion as much as I am

As we now know, seeing the EMD F-23 configurations, the weapons issue was solved with two separate weapons bays. Also, the only feature I can think of that the YF-23 had that the YF-22 didn't and ended up in the production version, was using the flight controls for deceleration as a opposed to a dedicated air brake. But, to me, that's just a refinement of the FCS.Reading through this thread again, I think some of the early takes require some corrections in light of more recent information.

Concerns about overheating of the aft fuselage were common to both the YF-22 and YF-23, but this was a solvable issue and it's no longer an operational concern for the F-22 after flight test validation. Similarly, the EMD F-23 would have had its engines toed in to be slightly closer but the volume between the nacelles would have had a fuel tank that would help act as a heat sink.

Regarding weapons bays, this has been discussed recently and while the F-23 has at least as much volume in this regard than the F-22, the geometry meant that weapons had to be stacked vertically, which current U.S. ordnance is generally not designed for. That said, I do think that this issue could have been resolved through EMD, perhaps by using an adapter similar to Sidekick that's currently planned for the F-35A/C which would bring the F-23's internal AMRAAM carriage to parity with the F-22. Overall, the added volume of the F-23 over the YF-23 in the weapon bays and fuel tanks may not help with drag but it would have enabled better operational characteristics. On the note of volume, I'm not sure if the F-23 would have been lighter than the F-22, especially since the F-23 is more voluminous with some 20% greater internal fuel tank capacity. BMI proved to be a tricky material to work with for both Lockheed and Northrop, and perhaps contributed to the F-22 having such a high percentage of titanium by weight (more than any fighter, I believe).

It's very unlikely that the F-22 borrowed any features from the F-23. The F-22 design certainly evolved as it went through PDR and CDR after the EMD down-select, but the outer mold line remained largely unchanged from what Lockheed submitted for EMD in December 1990, with the differences mainly in the panel lines. As such it's unlikely that the shaping of the F-22 took much influence from the YF-23; rather, this was likely because of the major design by the Lockheed team starting in summer 1987 resulting in the YF-22 being quite immature by the time it was frozen, so the F-22 had more room to evolve from the YF-22 than the F-23 from the YF-23.

Performance-wise, the YF-22's late redesign and changes before the design freeze meant that its aerodynamics weren't quite as refined as the YF-23, whose design saw a gradual progression from Northrop's Dem/Val submission and still greatly resembled it. The YF-23 did have superior performance in supercruise with speeds in the Mach 1.7 range, notably better than the YF-22's Mach 1.58 but not quite as much as what has been exaggerated over the years; I think many got carried away by the novel aesthetics. The much more refined F-22 can match the YF-23's speed but that said, any objective comparison is difficult to make because neither aircraft flew the same test points. Again, statements from the SPO indicate that both aircraft met requirements and while each had its advantages, neither were decisively better in performance.

Ultimately, I think the biggest benefit of the F-23 would have been the greater internal fuel capacity, and better all-aspect stealth. However, I don't think the advantages would have been great enough for what USAF is currently seeking from NGAD.

I’d be curious how this would work if the aircraft is statically unstable, which requires constant adjustments from the flight control computers. Perhaps some pre-determined deflection of control surfaces would be enough to shift the aerodynamic center further aft?In the event of a failure of this air data system, the vehicle would revert to fixed control gains.

Other aircraft also have this feature; it's usually limited to specific aircraft configurations and specific parts of the flight envelope to be able to recover to a very limited attitude envelope. Really more just like giving you more time for straight and level flight to eject, definitely nothing like full performance.I’d be curious how this would work if the aircraft is statically unstable, which requires constant adjustments from the flight control computers. Perhaps some pre-determined deflection of control surfaces would be enough to shift the aerodynamic center further aft?

The HMD and IRST were dropped to reduce risk IIRC.Sorry to interrupt your conversation, but I found this image while watching the documentary about the YF-23 uploaded by the Western Museum of Flight. You can find it at 15:14 in the video. I am not sure if this is a rendition of an F-23 or F-22 concept, but it seems to show an HMD targeting system. Is there any information that the F-23/F-22 were supposed to have an HMD?

Cost, primarily, I believe. IRST was dropped from F-15 for cost reasons too.The HMD and IRST were dropped to reduce risk IIRC.

Was an HMD prototype produced or was that dropped earlier in development?The HMD and IRST were dropped to reduce risk IIRC.

I see the picture you are referencing. The section of fuselage it was attached to just seemed quite different from the shape on the F-22 so I wasn't sure. That and the logo being the right-way up even though the whole assembly is flipped upside-down.Searching for 'IRST' in this same thread will bring you answers with pics. Fact that Lockheed wanted side-looking AESA doesn't obligatory mean that Northrop team wanted the same.

What is an MLD aperture? I couldn't find anything about that online.I see pair of MLD apertures at top and bottom though.

How does it do that?Missile Launch Detection (MLD).

I think most of that era was a dual band IR and UV, looking for the plume from the rocket exhaust.How does it do that?

During evaluation of the avionics in the simulator the pilots tested what kind of tactical or strategic difference the implementation of IRST would make to the combat outcomes. They found that having an IRST did not make a big enough difference in outcomes to justify the cost.I was intrigued by the provision for an IRST as shown in this drawing. Since it just uses IRST as a generic term, i assume that either: Northrop wanted to develop an IRST during EMD

use an existing one (AN/AAS-42?, Falcon Eye?)

or it is just meant to be there in case one is developed in the future.

Is there really no available info on what type this IRST was supposed to be?

View attachment 739743

In or about October 1992, the F-22 EMD 'chief engineer' (actually VP and Air Vehicle IPT Leader) Don Herring, RIP, asked me to sit in his conference room with Paul Metz, roll out the F-22A arrangement drawings, and 'walk around' the airplane. Apparently it was Metz's first day on the job in Marietta GA. He and I got right down to business -- no intros, no small talk, which left me a bit uncomfortable.I would sure like to hear "the straight dope" from Paul Metz some day.

Interesting, although I'm not sure what is being inferred here since it could be any number of things.Answering Question 2 is the only time his facial expression changed from that World Poker Tournament look.

The contractual performance spec and the Air Force's System Operational Requirements Document (SORD) defined supercruise simply as sustained speed in level 1g flight where Total Drag = Net Thrust in military power, equivalent to Ps = 0. Other operational limitations may be real constraints, but my guess is you'll run out of gas first.Interesting, although I'm not sure what is being inferred here since it could be any number of things.

As far as supercruise speed goes, the limitation may not just be driven by airframe shape but also engine temperature limits. Beyond a certain Mach number, inlet heating from adiabatic compression means that the engine won't be able to maintain rotor RPM for mil thrust, whether that be your compressor discharge or your TIT/FTIT. The F120 being a lower OPR engine than the F119 is perhaps less restricted in this regard, although it's also reportedly a thirstier engine.

I'd also be interesting in know how the inlet on the F-23 compares to the F-22. The former has a bumped compression surface with serrated cowling, while the latter has a caret compression surface. The YF-23's trapezoidal inlet did have some distortion issues, if I recall.

True, I was brainstorming more from a technical perspective on what may drive those limits for the airframe-engine combination.The contractual performance spec and the Air Force's System Operational Requirements Document (SORD) defined supercruise simply as sustained speed in level 1g flight where Total Drag = Net Thrust in military power, equivalent to Ps = 0. Other operational limitations may be real constraints, but my guess is you'll run out of gas first.

Zilch, nada. He couldn't have had a flatter affect. Then again, it was my first and only time interacting with someone possessing the Right Stuff -- but even the mighty Chuck Yeager would yuck it up.True, I was brainstorming more from a technical perspective on what may drive those limits for the airframe-engine combination.

I believe Tony Chong's 2016 book Flying Wings & Radical Things stated that based on the YF-22 with YF120 reaching Mach 1.58 supercruise, General Electric engineers estimated that the YF-23 with their engines could be pushed to around Mach 1.8 or so in supercruise, although I don't believe PAV-2 was actually tested to this speed as PAV-1 with the P&W engines was the flutter test vehicle for envelope expansion.

Based on his reaction from your 1992 meeting with him, did Metz give any inklings on what the PSC F-23 was supposed to achieve?