- Joined

- 19 February 2007

- Messages

- 1,430

- Reaction score

- 2,648

I've been researching North American Aviation designs for quite a while. By now, everyone knows (or should know)

that NAA used a rather unique designation system. Most of the US manufacturers used a “model” numbering

system that was generally sequential. Each model number was tied to a basic design. NAA for reasons unknown,

chose a road less traveled. Each NA-number was not a model number tied to an aircraft, but a master charge

account number tied to a single specific customer contract. Thus, you have the F-100 Super Sabre produced under

Charge Numbers NA-180, 192, 217, 222, 223, 224, 230, 235, 243, 245, 254, 255, 261, and 262. In a way, this was

“inside-out” because it exposed a little of the inner workings of NAA to the outside world.

However, this numbering scheme left no room for designations of the actual designs pursued by NAA. My first clue

came in the Jenkins/Landis book, “Hypersonic, The Story of the North American X-15”. In it was an entire chapter

covering the proposals by Bell, Douglas, North American and Republic. North American’s design was titled “ESO 7487”

and was referred to as such in the text.

On the face of it, this designation seemed absurd to me for two reasons. First, I interpreted “ESO” to mean

"Engineering Sales Order" or "Engineering Shop Order". Secondly, “7487” seemed improbably high for a project or

design number. Even the government project number (MX-1226) was lower. Ultimately, the decision of the authors

to provide blue-line drawings on the book end papers provided a clue. The drawing from North American had a title

block. Above it was “ESO 7487”. But in the block proper was the actual Drawing Number – “D250-200”.

Having some experience with aerospace drawings and Configuration Management practices, this made a lot more sense

to me. “D250” would be the “top” drawing or project number. The “-200” or dash number would be the allocated

number for what was depicted in that drawing. And “250” seemed like a much more reasonable cumulative number for

a design.

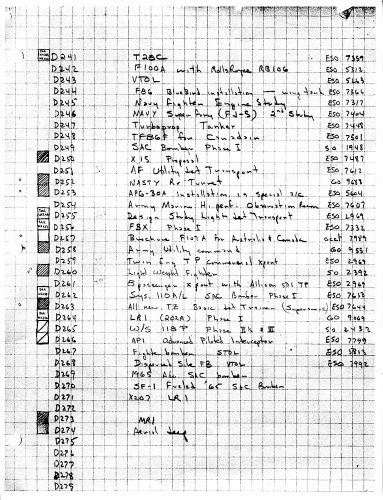

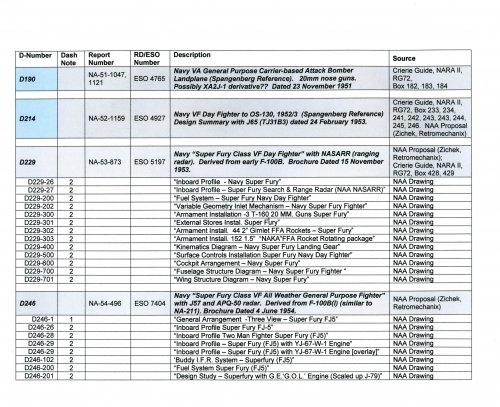

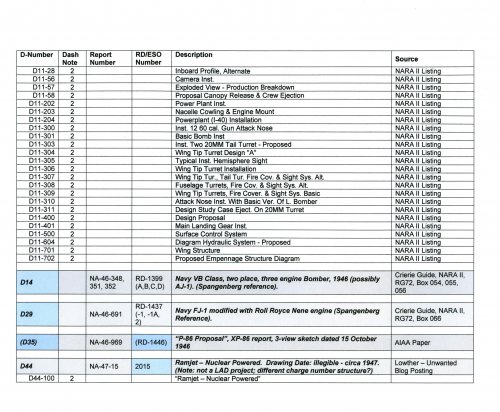

To make a long story short, I surveyed all of my references, Secret Projects Forum postings and the interwebs and

came up with the following listing. Please note that I have included abbreviated notes for my sources; most

should be familiar.

So what does it mean? Simply put, NAA maintained an internal system for tracking preliminary or advanced designs

that was unrelated to the “NA” series of contract/charge numbers known publicly.

Why does the drawing number matter? Basically it tells you what you are looking at. The basic number was of the

format Dxxx, where “D” presumably meant “Design” and “xxx” was a sequentially assigned number. When used on a

drawing, the basic number had a suffix. The first 25 numbers were reserved for alternate basic configurations.

The next 25 were for inboard profiles of the corresponding configurations. So drawing D250-1 would have an inboard

profile on drawing D250-26; D250-2 would track to D250-27 and so on. Subsequent drawing blocks appear to be generally

assigned as follows:

-1 to -25 Three-view

-26 to -50 Inboard profile

-200 Fuel System

-300 Weapons Installation

-400 Landing Gear

-500 Surface Control System

-600 Hydraulic System or Cockpit Diagram.

-700 Structures

Sometime by the 1960s, the system was modified by inserting another set of digits in the D-number so that more design

variations could be tracked. An example would be the drawing D619-10-26 where the basic project is “D619”, “10” is the

tenth major study or design and “26” is the inboard profile drawing that corresponds to the “D19-10-1” three-view drawing.

Sometimes the study number has an alpha suffix (as in D490-4B); I suspect that this is an alternate engine installation.

Looking back, this seems to be an internally consistent system that holds together with multiple samples. But what about

those pesky four-digit numbers? My conclusion is that they are actually the project charge numbers. The fly in the

ointment? North American specifically used the phrase “designated ESO 7487” on the title page of its X-15 proposal.

It is my belief that using the internal Charge Number served two purposes; first, a bit of misdirection as to the

number of designs that North American had studied; and secondly, it was in concert with the unusual practice of using the

charge number in lieu of a model number in general.

I’d like to express my thanks to (in no particular order) Dennis Jenkins, Tony Landis, Scott Lowther and Jared Zichek

for not only performing the painstaking primary research on these designs but for also reproducing the original drawings

with their title blocks intact. Ryan Crierie also deserves special mention for sharing his index listings for

documentation held at the National Archives (NARA II). Special supplemental assistance was also provided by Bob Bradley.

Any comments or questions are welcome.

that NAA used a rather unique designation system. Most of the US manufacturers used a “model” numbering

system that was generally sequential. Each model number was tied to a basic design. NAA for reasons unknown,

chose a road less traveled. Each NA-number was not a model number tied to an aircraft, but a master charge

account number tied to a single specific customer contract. Thus, you have the F-100 Super Sabre produced under

Charge Numbers NA-180, 192, 217, 222, 223, 224, 230, 235, 243, 245, 254, 255, 261, and 262. In a way, this was

“inside-out” because it exposed a little of the inner workings of NAA to the outside world.

However, this numbering scheme left no room for designations of the actual designs pursued by NAA. My first clue

came in the Jenkins/Landis book, “Hypersonic, The Story of the North American X-15”. In it was an entire chapter

covering the proposals by Bell, Douglas, North American and Republic. North American’s design was titled “ESO 7487”

and was referred to as such in the text.

On the face of it, this designation seemed absurd to me for two reasons. First, I interpreted “ESO” to mean

"Engineering Sales Order" or "Engineering Shop Order". Secondly, “7487” seemed improbably high for a project or

design number. Even the government project number (MX-1226) was lower. Ultimately, the decision of the authors

to provide blue-line drawings on the book end papers provided a clue. The drawing from North American had a title

block. Above it was “ESO 7487”. But in the block proper was the actual Drawing Number – “D250-200”.

Having some experience with aerospace drawings and Configuration Management practices, this made a lot more sense

to me. “D250” would be the “top” drawing or project number. The “-200” or dash number would be the allocated

number for what was depicted in that drawing. And “250” seemed like a much more reasonable cumulative number for

a design.

To make a long story short, I surveyed all of my references, Secret Projects Forum postings and the interwebs and

came up with the following listing. Please note that I have included abbreviated notes for my sources; most

should be familiar.

So what does it mean? Simply put, NAA maintained an internal system for tracking preliminary or advanced designs

that was unrelated to the “NA” series of contract/charge numbers known publicly.

Why does the drawing number matter? Basically it tells you what you are looking at. The basic number was of the

format Dxxx, where “D” presumably meant “Design” and “xxx” was a sequentially assigned number. When used on a

drawing, the basic number had a suffix. The first 25 numbers were reserved for alternate basic configurations.

The next 25 were for inboard profiles of the corresponding configurations. So drawing D250-1 would have an inboard

profile on drawing D250-26; D250-2 would track to D250-27 and so on. Subsequent drawing blocks appear to be generally

assigned as follows:

-1 to -25 Three-view

-26 to -50 Inboard profile

-200 Fuel System

-300 Weapons Installation

-400 Landing Gear

-500 Surface Control System

-600 Hydraulic System or Cockpit Diagram.

-700 Structures

Sometime by the 1960s, the system was modified by inserting another set of digits in the D-number so that more design

variations could be tracked. An example would be the drawing D619-10-26 where the basic project is “D619”, “10” is the

tenth major study or design and “26” is the inboard profile drawing that corresponds to the “D19-10-1” three-view drawing.

Sometimes the study number has an alpha suffix (as in D490-4B); I suspect that this is an alternate engine installation.

Looking back, this seems to be an internally consistent system that holds together with multiple samples. But what about

those pesky four-digit numbers? My conclusion is that they are actually the project charge numbers. The fly in the

ointment? North American specifically used the phrase “designated ESO 7487” on the title page of its X-15 proposal.

It is my belief that using the internal Charge Number served two purposes; first, a bit of misdirection as to the

number of designs that North American had studied; and secondly, it was in concert with the unusual practice of using the

charge number in lieu of a model number in general.

I’d like to express my thanks to (in no particular order) Dennis Jenkins, Tony Landis, Scott Lowther and Jared Zichek

for not only performing the painstaking primary research on these designs but for also reproducing the original drawings

with their title blocks intact. Ryan Crierie also deserves special mention for sharing his index listings for

documentation held at the National Archives (NARA II). Special supplemental assistance was also provided by Bob Bradley.

Any comments or questions are welcome.

Attachments

-

NAA D-Series Page 1.jpg941.5 KB · Views: 703

NAA D-Series Page 1.jpg941.5 KB · Views: 703 -

NAA D-Series Page 8.jpg592.1 KB · Views: 117

NAA D-Series Page 8.jpg592.1 KB · Views: 117 -

NAA D-Series Page 7.jpg223.1 KB · Views: 117

NAA D-Series Page 7.jpg223.1 KB · Views: 117 -

NAA D-Series Page 6.jpg962.5 KB · Views: 125

NAA D-Series Page 6.jpg962.5 KB · Views: 125 -

NAA D-Series Page 5.jpg1,001.2 KB · Views: 447

NAA D-Series Page 5.jpg1,001.2 KB · Views: 447 -

NAA D-Series Page 4.jpg1,020.4 KB · Views: 483

NAA D-Series Page 4.jpg1,020.4 KB · Views: 483 -

NAA D-Series Page 3.jpg945.1 KB · Views: 527

NAA D-Series Page 3.jpg945.1 KB · Views: 527 -

NAA D-Series Page 2.jpg921.1 KB · Views: 636

NAA D-Series Page 2.jpg921.1 KB · Views: 636