- Joined

- 27 December 2005

- Messages

- 17,722

- Reaction score

- 26,241

Looks like third contractor was Thule

Not that I recall.

It was a joke I think. Thule make bike racks and roof boxes.

Looks like third contractor was Thule

Not that I recall.

Thanks, that we really informative.. But rather than backtrack on the executive decision to use the darned things, we stuck with them to the end. So glad to see the program disappear!

I don't think air intakes above the wings or fuselage are all that bad, they must have there advantages, other wise the B-2, B-21, Tacit Blue, the new MQ-25, X-45, X-47 and so on, didn't use them, the X-47 had a refueling probe on the side fuselage, and the B-2 has one on top of the fuselage, and no fuel ingestion was a problem, i can at least agree, that for supersonic high manobrable aircraft, air intakes above the fuselage, can prove a bit of a chalenge to work with.Not that I recall. McDonnell-Douglas selected the overhead inlet concept, we were told at the time, because the program manager was walking through the area where the configurators were laying out ordinary-looking things with big inlets on the sides of the fuselage, except for one very young person who, for reasons unknown, had sketched them up on top instead. PM thought that would make our airplane immediately stand out visually from a crowded field of competitors and so he decided to make that the centerpiece of our whole design. It was purely MDC's concept and decision to use it. The combined duct was cantilevered out above the fuselage for I believe 6-8 feet, which caused problems with keeping it rigid. There was nowhere to put either a USAF-style refueling receptacle or a USN-and-everybody-else probe, because the fuel spilled on disconnect wouldn't go straight down those inlets and into the engines, where China Lake had already done enough testing on fuel ingestion to warn us that drastic problems were likely to result. Any kind of positive angle of attack involved problems maintaining undisturbed airflow into the inlets. And so on. But rather than backtrack on the executive decision to use the darned things, we stuck with them to the end. So glad to see the program disappear!

Because none of them have UARRSI in front of inlets and they have space and volume for receptacle while MDC/Vought A/F-X just didn't have it as was said before.the X-47 had a refueling probe on the side fuselage, and the B-2 has one on top of the fuselage, and no fuel ingestion was a problem

Well, I worked on the advanced bomber proposal and on the MQ-25, and neither of them anticipated going to high angles of attack like A/F-X was supposed to do, so turbulence at the inlet duct isn't the same kind of problem for them. I can only tell you that on our A/F-X there was literally nowhere we could mount the refueling stuff, and we had world-class experts struggling with the problem.I don't think air intakes above the wings or fuselage are all that bad, they must have there advantages, other wise the B-2, B-21, Tacit Blue, the new MQ-25, X-45, X-47 and so on, didn't use them, the X-47 had a refueling probe on the side fuselage, and the B-2 has one on top of the fuselage, and no fuel ingestion was a problem, i can at least agree, that for supersonic high manobrable aircraft, air intakes above the fuselage, can prove a bit of a chalenge to work with.

As Steve noted, you run into inlet distortion issues really fast at high alpha, especially if the inlet is set back on the fuselage and the aircraft has any sort of strake. Any bit of yaw and that vortex is going into the inlet. You'll notice on many of the modern fighter designs now with a dorsal inlet, they are much more forward on the fuselage. This is done to keep them out of the powerful high alpha vortices and limit the blanking effect caused by the fuselage.I don't think air intakes above the wings or fuselage are all that bad, they must have there advantages, other wise the B-2, B-21, Tacit Blue, the new MQ-25, X-45, X-47 and so on, didn't use them, the X-47 had a refueling probe on the side fuselage, and the B-2 has one on top of the fuselage, and no fuel ingestion was a problem, i can at least agree, that for supersonic high manobrable aircraft, air intakes above the fuselage, can prove a bit of a chalenge to work with.

Can also be done with LERX, but that's something of an exception to the rules.Handley Page 115 took the opposite approach with highly swept wings to generate really strong stable vortices either side of the dorsal intake at the rear. It would merrily fly along at about 35deg AoA.

I think that was mostly due to the non dogfighting nature of the expected mission(s), though I'd wonder about doing a rapid pull-up during TFR flight.Makes me wonder why, in the TFX competition, the USAF and Navy preferred the Boeing design over the GD design, with its intakes being on top of the fuselage and at almost exactly the mid-length point.

View attachment 706168

Do you have any references for these programs by chance?At the time, USN as an institution did not realize how low the signatures could go for a number of reasons. USN actually had run a number of their own LO programs previously, which may have lead them to false assumptions about the lowest practical signatures - and how to get there.

Do you have any references for these programs by chance?

It costs some amount of RCS, the hinge pin bulge really ruins the outer mold line.How stealthy can a swing-wing really be? It can't be that much of an issue if they considered putting one on an F-22.

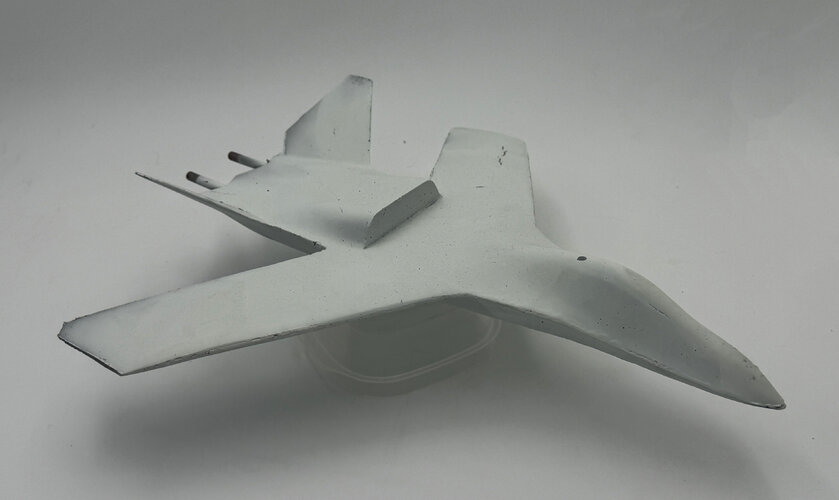

in-house McDonnell model mold marked AX that is in my possession, so my peepers can confirm all aspects of the model and its heritage and the labeling. It's missing the doghouse and sadly there is no sign of this particular mold, so when I finish this I will need to be creative when constructing. Does anyone out there have ANY information on the design and what we are dealing with here?

in-house McDonnell model mold marked AX that is in my possession, so my peepers can confirm all aspects of the model and its heritage and the labeling. It's missing the doghouse and sadly there is no sign of this particular mold, so when I finish this I will need to be creative when constructing. Does anyone out there have ANY information on the design and what we are dealing with here?AWST 28 Sep 1992Consensus Emerging for AX Strike-Fighter

(JOHN D. MORROCCO)

A s the Navy moves closer to setting its requirements for the AX, a consensus is emerging for a multimission strike fighter aircraft with an increased emphasis on endurance rather than range. Rear Adm. Riley Mixson, Navy director of air warfare, said the Air Force and Navy are ”coming to closure” on requirements. Although the Navy has the lead on the program, the AX also is being designed to replace Air Force F-111, F-15Es and F-117s.

Mixson told AVIATION WEEK & SPACE TECHNOLOGY that the two services ”are seeing very much eye to eye on the roles and missions and performance capabilities that we would want to expect from an aircraft of this type. . . . We envision it as more of a multimission type of aircraft than perhaps was originally intended, certainly more than was intended with the A-12 program.”

Because of the current budgetary climate, the Navy is paring down to two combat airplanes—”a lowend and highend mix,” Mixson said. The F/A—I8E/F represents the low-end of the mix. ”The high-end is going to be the AX, which is taking on more and more of the flavor of a multirole strike fighter,” he said. ”The Navy cannot afford a single-purpose aircraft.”

AX requirements are not only being shaped by economic necessity, but also by the debate over roles and missions. The Navy has reexamined the AX pro

gram in the context of an increased emphasis in the future on coastal and amphibious operations, to meet regional threats.

Mixson said the Navy and Air Force hope to finish defining their AX requirements by the end of the month or early October. That will coincide with the results of cost and effectiveness analyses now being conducted by both services, based on trade studies submitted last June by the five competing contractor teams.

If this airplane coincides with what we see as the future roles and missions of the Navy/Marine Corps team, then a request for proposals would be coming some time after that,” Mixson said. Contractors expect to receive an operational requirements document in late October. They will then work on updating their designs to meet the final requirements.

The Pentagon’s Defense Acquisition Board is scheduled to review the program in early November. Requests for proposals for the demonstration/validation phase are expected to be issued to contractors in early December.

THE TIMETABLE could change, however. Navy officials indicate there is no need to rush to judgment. ”With today’s threat we have time to make sure the AX isexactly what we want it to be,” Mixson said, If the cost and effectiveness analyses indicate ”we should look in another area or we should study this a little bit more, we do not feel we are on a constrained time line by any stretch of the imagination.”

The Navy’s tentative requirement, which contractors based their trade studies on, included levels of speed, signature and payload that did not necessarily

reflect a multimission strike fighter. Subsequent Navy studies are now ”showing us you need both” an air-to-ground and air-to—air capability, Mixson said. ”If you are going to put an investment in stealth, then you want to be able to send that aircraft and have it defend itself against any petential air-to-air threat.”

The move to more of a strike-fighter does not necessarily require a supersonic aircraft, Mixson said. ”There is a lot of engine technology out there today that enables you to do things without being in an afterburner mode to get the speed that you require.” Industry officials said they did not expect there would be a requirement for a supercruise capability like that of the Air Force's F-22.

said the level of stealth needed in the AX has not changed and will probably reflect current—generation technology. ”Stealth brings you an added dimension in the air-to—air role as well as the air-to—ground role,” he said. ”Without air superiority, you don’t move troops very well on the ground.”

The increased emphasis on determining what will be required in an AX aircraft to support ground operations has been largely spurred by the roles and

missions review. With the demise of the Soviet threat, the Navy is now shifting its focus toward power projection from the sea in regional conflicts.

Navy Secretary Sean O'Keefe said that while the Navy required an aircraft that could accomplish the missions now carried out by the A-6, the future emphasis will be on ”littoral” conflicts, involving coastal and amphibious operations. That means ”a shorter range, bring-an-awful- Iot—of—ordnance-to-bear capability that could be provided for Marine landings,” he said. ”That doesn’t mean you have to go incredible distances.”

Mixson said that while range is an important consideration, he was more concerned with endurance, which is an important factor in flexibility for carrier

operations. ”What I want is an airplane that I can send out on a mission and have it come back and land aboard ship without refueling on a nominal carrier cycle of about 1 hr. 45 min.,” he said. ”That translates to on endurance of a little over 2 hr.”

Along with that comes a certain amount of range, roughly 600 naut. mi. ”With a 600-naut.-mi. range and that endurance I’ve got a lot of flexibility,” he

said. ”That doesn’t mean we are out of the strike role,” Mixson said. ”That’s still an important part of our mission. But I think we are focusing a little bit more on sup port of troops ashore than we might have in the past with our ’Open Water’ maritime strategy.

AWST 5 October 1992Navy Eyes Delay in AX Development

(JOHN D. MORROCCO)

Refinements in Navy and Air Force requirements and a desire to fully explore new technological advances could slip the AX development schedule by two years. Vice Adm. William Owens, head of the Navy’s new office of resources, requirements and budget, said that the program ”has been delayed a couple of years” to allow ”the right kind of deliberation with the Air Force.” But he later retracted the statement, saying it was ”not a done deal” and that no official decision has yet been made.

A senior Air Force official indicated, however, that the stretch-out is virtually certain. ”They discovered our plan is more appealing, now that they’ve realized theirs is unworkable," he said. ”The Navy would have had to slip the program two years anyway.”

OWENS’ COMMENTS were made in the context of the ongoing review of service roles and missions and what impact this would have on procurement decisions. The emphasis in the future would be on "jointness,” he said. ”In the programmatic world, a lot of that brings us into volume buys, more efficiencies, and a better common look at what we need in the area of tactical aviation.”

”As the Air Force looks at the F—22, for instance, we recognize that much of that technology will be relevant to our advanced aircraft, be they the F/A-l 8E/F or AX,” he said. ”So what I see is a lot more progression to common engines, electronics, et cetera, as we look to the future.”

A senior naval aviation official said ongoing cost and effectiveness analyses may generate changes that would result in the program being pushed back. One change being considered is capitalizing on improvements in engine technology. The Air Force has proposed exploring a new-technology engine for the AX, which is also being designed to replace the service’s F-117s and F-111s. That would require more time to develop than allowed in the current plan for a four-year demonstration/validation program.

A six-year demonstration phase would mean the Navy would not have to fund the more expensive engineering and manufacturing development portion of the AX program in its forthcoming six year budget plan. That would ease funding problems in relation to the Navy’s F/A-18E/F upgrade program, since the current plan creates a large spike in annual funding requests for both aircraft in the 1996—97 time frame.

Navy officials were quick to point out that Owens’ comments were in line with earlier pronouncements by Navy Secretary Sean O'Keefe that there is no rush to make quick decisions on the AX program. O’Keefe made it clear that, since the program is still in its early stages, he would like to keep as many options open as possible. But at the same time, Navy officials sought to reassure industry that the program is still on track.

”Contractors are going crazy” because of the uncertainty over the program’s direction and schedule. They want a ”decision as soon as possible,” one Pentagon official said. Following Owens’ remarks, Navy acquisition chief Gerald Cann quickly pointed out that the Navy still plans to issue requests for proposals to industry this fall for the demonstration/validation phase of the program.

”Up to now, the AX schedule has been notional in nature without the benefits of industry’s inputs,” Cann said. The Navy is now introducing the results of AX concept exploration and definition studies from the five contractor teams "to adjust the notional schedule," which will be presented at the Defense Acquisition Board review scheduled for early November. The ”real” schedule will be based on the winning industry proposal.

Uncertainty over the AX acquisition program has been fueled by a number of factors. One is the move in Congress tohave the Navy select two contracting

teams to build competitive prototypes rather than just one, as the service has proposed. Another is uncertainty over future budget decisions, especially in light of the upcoming presidential elections. A third factor is the shift of emphasis within the Navy over the past six months regarding its requirements. A consensus is emerging for a multi-mission, strike fighter (AW&ST Sept. 28, p. 26).

An Air Force official said there has been ”good alignment” between the Air Force and Navy on the joint operational requirements document for the aircraft. But the Navy has yet to sign off on the document. The official said there appeared to be an internal conflict within the Navy about the definition of the aircraft's role and how much fighter capability should be designed into the aircraft.

AWST 23 Sept 1991McDonnell Revamps New Aircraft Product Div.

To Compete for AX, Multirole Fighter McDonnell Aircraft Co. has reorganized its New Aircraft Product Div. to place more emphasis on prototyping capabilities as it competes for the Navy’s AX and the Air Force’s multirole fighter programs.

NAPD was created in 1987 after Mc-Donnell Douglas’ failure to be selected as one of the prime contractors for the Air Force’s advanced tactical fighter (AW&ST Oct. 26, 1987, p. 84). At the time, its focus was on developing the technical resources necessary for next-generation weapon systems. The division was restructured this past May, shortly after the Navy’s cancellation of its contract with General Dynamics and McDonnell Douglas for the A-12 and the failure of the Northrop/McDonnell Douglas F-23 to win the Air Force’s ATF contract. Neither of those efforts was under NAPD’s control, but they were separate program efforts within the company.

In essence, NAPD has been transformed from an engineering division into a product division that reports directly to the president of McDonnell Aircraft, John Capellupo. The emphasis is now on developing technology investment and business strategies to apply design, structures and manufacturing technologies to specific future programs.

Specifically, NAPD will now include all new program efforts, including the company’s work on the National AeroSpace Plane, AX and multirole fighter projects. It will shepherd those efforts from concept definition through the demonstration/validation phase, includingprototype development.

James Sinnett, who headed NAPD in its early years, is in charge again. “The big change that has occurred is to reinforce our emphasis and commitment to establishing a prototype capability within McDonnell Aircraft,” he said. The division now has a separate prototyping subdivision. In addition to prototyping aircraft, the division is focusing on prototyping advanced manufacturing technologies.

NAPD’s materials process and development efforts also have been expanded dramatically, Sinnett said. It now incorporates tooling materials and concepts, including disposable tools, as well as support concepts for routine maintenance and battle damage repair.

The goal is to better integrate a broad spectrum of technologies and disciplines that have become increasingly fragmented. In a disciplined engineering process, designers understand what is needed to fabricate and assemble the aircraft. “That is part of the whole engineering job instead of designing something and throwing it over the wall for somebody to tool and then throwing it over another wall for somebody to build,” he said. “Each time you throw it over it comes back, so there is a lot of rework that goes on.”

One of the biggest challenges facing NAPD is trying to recover the contract for the Navy’s medium attack aircraft replacement. The cancellation of the A-12 program dealt a heavy blow to the company both financially and politically. The failure of the McDonnell Douglas/General Dynamics A-12 team could taint their prospects for the follow—on effort. McDonnell Douglas has two efforts under way (AW&ST July 22, p. 18). It is teamed with prime contractor General Dynamics in offering an A-12 derivative. The roles and responsibilities will remain basically the same as when the program was terminated, with some exceptions.The major exception is that General Dynamics would be responsible for final assembly and fly-out.

McDonnell is also the prime contractor, with LTV as the principal subcontractor, in a teaming arrangement to offer a new design.

In the former effort, “the fundamental strategy is to save the technical sense of what we know from the A-12 program, which includes all of the design and trade studies and a lot of the process techniques,” Sinnett said. Two major stumbling blocks, however, are the changes in the requirements made by the Navy from the A-12 to the AX and the issue of who owns existing A-12 technologies and tooling.

The Navy issued requests for proposals to industry for AX design concept studies earlier this month that differed from the A-12 in some key respects (AW&ST Sept. 9, p. 26). The volume required inside the AX is less than for the A-12, for example; therefore, the size of the aircraft will be smaller. Shrinking the A-12 is probably not the answer, but neither is a new start, Sinnett said. The two firms are looking to see what systems and technologies from the A-12 can be applied to meet the new requirements.

TECHNICAL-POLITICAL FINE LINE

Sinnett admitted that requirement changes posed a difficult challenge and that the team was walking a fine line between what makes technical sense and what makes political sense. “However, I believe we have to be there with that kind of a solution, should that be the desired path.” There has been enough maturation of technology over the past five years, “that would give us some advantage in making the changes to what was the A-12 configuration,” he said. “To the extent that we can do that and not throw out the baby with the bathwater, that really would be the approach on an A-12 derivative.” But a key unanswered question is ownership of existing A-12 aircraft and technologies. “It’s extremely complicated and difficult to sort out,” Sinnett said. “The question really revolves around what is construed as assets and who owns them.”

The Navy maintains it owns technical data submitted by the contractors for which it paid $1.33 billion and has rights to work in progress at the time the contract was canceled. General Dynamics and McDonnell Douglas completed approximately 99% of the engineering drawings and had fabricated about 85% of the tools needed to assemble A-12 parts, according to the General Accounting Office.

The government has not sought to appropriate any of the work, but in June the contractors were informed they had to obtain the Navy’s approval before they could dispose of any A-12 property. The government instead has demanded the repayment of $1.3 billion in progress payments made to the two firms for the work. A suit filed by McDonnell Douglas and General Dynamics in June in U. S. claims court challenging the Navy’s contract termination for default, which would in effect nullify the Navy’s claim, is still pending (AW&ST June 17, p. 213).

Regardless of the outcome concerning A-12 assets, Sinnett said the knowledge acquired by those who worked on the program will go a long way to provide a competitive advantage in terms of a derivative of the A-12.

Sinnett said he expected fewer problems in terms of weight growth on an A-12 derivative than were experienced on the A-12. “There has been an enormous influx of knowledge on deep-depth composite structure that makes us a little bit smarter than we were five or six years ago." The internal rearrangement of the design may also lend itself to a more efficient use of structural concepts than were employed in the A—12, he said. As a result of the A—12 experience, the Navy and contractors will be paying much closer attention to weight control “simply to preclude any kind of a disaster occurring again.”

McDonnell is still working out many of the details of its teaming arrangement with LTV on a new AX design. Sinnett said LTV was selected because of its impressive record in designing and building structures. LTV also offered a great deal of experience building carrier suitable aircraft and in transitioning low-observable design and development to production. LTV is a major subcontractor to Northrop on the B-2 bomber program.

The McDonnell/LTV effort will be separate from the General Dynamics/McDonnell A-12 derivative program, but both will be housed within NAPD. The McDonnell/LTV team is still reviewing the Navy’s request for proposals. Sinnett said the Navy is providing quite a lot of leeway to AX competitors in offering design concepts, but said the service is committed to evaluating all concepts before it determines what the initial configuration should be. He noted, however, that all indications point to the Navy’s desire for an attack aircraft with some fighter or self-defense capabilities.

Both McDonnell and Northrop have ruled out proposing a strike-fighter version of their ATF candidate—the YF-23. The two companies came to parallel

conclusions that they would be offering “too much airplane for what the role and mission of the AX would be,” Sinnett said.

“We have some real concerns about weight and cost and the ability to get it aboard a carrier.” McDonnell is also working on designs to meet the Air Force’s requirement for a new multirole fighter. The service will look at derivatives of existing aircraft as well as new designs. Concept definition study contracts are expected to be awarded early next year (AW&ST July 22, p. 38).

Sinnett said the firm is mainly concentrating on a new aircraft design, drawing on its experience from building multirole aircraft, such as the F/A-18 and F-15E. Although the firm is not considering offering a derivative of the F/A-18, it is looking at an F-15 option for the multirole fighter.

“While people rule out the F-15 as too much airplane, we are taking a look to see whether there is any potential benefit to offer it as an MRF,” he said. The company will look to see if the potential exists to simplify or modernize the aircraft to enhance its affordability and life-cycle costs.

A new design seems more likely, however. “We think there is significant enough change in the operational spectrum and operational requirements, fundamentally in terms of affordability and life-cycle costs, that would lean toward a new design,” Sinnett said. “Absolutely, we need to look at enhancing our ability to produce low-cost materials.”

NAPD is working on a new composite material and manufacturing process for submarines under a research contract with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency that may be appropriate for a new multirole fighter. The advanced fiber placement program fundamentally involves developing machine tools to manufacture a thermoplastic composite material.

At the same time the fiber is laid, it is cured with a “hot laser head,” Sinnett said. While the process may result in a weight penalty of 1 to 1 1/2%, fabrication costs could be reduced by 25-40%. “If one could realize as much as a 30-40% benefit of producing thermoplastic composites, one might be very willing to give up the 1 to 1 1/2% disadvantage in design allowables [weight],” he said. Another related contract with DARPA involves embedding fine hairs of fiberoptic material in composite materials to monitor the manufacturing process. “It doesn’t take much imagination to extend that and say that same embedded sensor capability may be waveguides for smart skin structures,” Sinnett said.

AWST 2 July 1991AX Competition Critical To Many Team Members

Most of the industrial teams are now in place to compete for the U. S. Navy’s next-generation AX attack aircraft, a program that could make or break some major companies in the financial and structural upheaval in the aerospace industry.

Among the competing teams and their entries are General Dynamics Corp. (prime) and McDonnell Douglas Corp, which will offer up a derivative of the A-

12 Avenger, which was terminated in January; Lockheed Corp. (prime), General Dynamics and The Boeing Co., which will propose a derivative of their U. S. Air Force F-22 (formerly known as the advanced tactical fighter); Grumman Corp. (prime), Lockheed and Boeing, which will propose a clean-sheet design, and Mc- Donnell Douglas (prime) and LTV Corp, which also will offer a new design.

Each of these teams is preparing to respond to the Navy‘s request for proposals for the program’s concept exploration phase, which is expected to get under way in the fourth quarter of 1991. The Navy will award five one-year, $10-million contracts during the last quarter of 1991. Team members have agreed among themselves to participate on only one clean-sheet design team.

Grumman also is considering proposing an advanced version of its carrier-based F-14D fighter as an AX candidate. Grumman officials expect to make a final determination within days.

In addition, Northrop Corp, the prime contractor on the U. S. Air Force B-2 strategic bomber, expects to be among the AX competitors but is reserving judgment on the nature of its participation until the Navy issues its RFP next month.

GUARDING AGAINST COMPROMISE

Similarly, Rockwell International Corp. will not make a decision on AX until the Navy issues the RFP. The company has not ruled out any teaming options, although its participation seems less certain than Northrop’s.

The fact that some companies are participating on more than one team suggests there could be the potential for them to compromise competing technologies or business strategies, but industry officials said they intend to take steps to guard against such an occurrence.

For example, McDonnell Douglas will have two totally autonomous teams. One will develop a clean-sheet AX design and the other team will work on a design based on technology originally developed for the A-12. These teams will be physically separated, workers will report to different senior managers, and no one on either team will have cross-clearances that could give him access to what the other team is doing. They will work as though they were

with competing companies,” James Restelli, executive vice president of McDonnell Aircraft Co., said.

The shrinking military budget—and the industry shakeout that is likely to result in the mid-l990s—makes the AX contract a must-win for some airframe makers. Production of many of the military’s front-line aircraft is winding down, and their builders are scrambling for new business, domestically and overseas. AX is one of the few major opportunities left for companies to make large additions to their backlogs on the strength of a single program.

Without AX, some companies may be forced out of the military-airframe business altogether. Moreover, all losers will forfeit the potential of billions of dollars in added revenue and the competitive edge that goes with producing an advanced combat aircraft for the U. S. Even Lockheed, which is the prime

contractor on the F-22, considers AX a high priority.

“There is a misperception that our F-22 win suddenly turned Lockheed into a fat cat, but we won’t begin making [big] money on that program for years," Thomas Burbage, Lockheed’s vice president of business development and product support, said. “We have got to keep fighting the battle every day to position ourselves for the future; AX along with ATF will determine the winners and losers for the next 20-30 years.”

AX is intended to replace the carrier-based Grumman A-6 Intruder, a two-seat, all-weather bomber for deep strikes and close-air support. It will not become operational until around 2005. The A-6 became operational in 1963. About 100 of the 470 aircraft now operating have been fitted with new Boeing Co. composite wings to extend the bombers’ service life. Eventually, however, the Navy will be forced to introduce a next generation strike aircraft.

The General Dynamics/McDonnell Douglas A-12 had been the intended replacement. But Defense Secretary Richard B. Cheney canceled the program because of cost and schedule overruns. While contractors still do not know exactly what the Navy’s AX requirements will be, they do have broad design criteria, based on the Navy’s tentative operational requirements. The Navy’s priorities are carrier suitability, affordability, survivability, air-to-surface effectiveness and air-to-air effectiveness.

“The Navy has a set of requirements to fulfill its medium-attack needs, and it has a range of other capabilities in the ‘desired’ category,” Paul Bavitz, Grumman’s vice president of advanced program development, said. “Navy officials will be looking to industry to tell them what is affordable.” This means contractors proposing a clean-sheet design will be entering the concept exploration phase with no biases toward airframe size, crew size, propulsion or any other criteria.

Further, while stealth will figure prominently in the winning AX proposal, it will not be an overriding design consideration. The Navy is encouraging companies to adopt a balanced approach to survivability and give equal consideration to speed, agility and electronic countermeasures, industry officials said. “The Navy will be examining the proposals carefully to determine ‘break points’ in cost, and where it does not make sense to pour a lot of money in to gain a certain capability,” Gerald A. Cann, assistant secretary of the Navy for research, development and acquisition, said.

This is welcome news to security analysts, who have been critical of new aircraft development programs that seem to have emphasized cutting-edge technology at the expense of cost-related issues, greatly increasing the financial risk to contractors. Such was the case on the A-12 program, for which General Dynamics and McDonnell Douglas wound up taking $700 million and $350 million in charges, respectively, against 1990 earnings. Industry officials expect the AX contract’s terms and conditions to be far more favorable than those for the A-12 program, which was a fixed-price development program.

NO 1992 FUNDING

“Hopefully, the government realizes the most appropriate type of contract for this type of project is cost-plus for the fullscale development phase,” Lawrence Harris, a senior analyst with Kemper Securities, Inc., said. There is no money requested for AX in the proposed Fiscal 1992 budget. Initially, the program will be funded with $167.5 million in research and development money earmarked in the Fiscal 1991 budget for AX and A-12 “mop-up” costs, Navy officials said.

Of the contractor teams already formed, the Grumman/Lockheed/Boeing alliance is among the strongest. Grumman contributes its experience in carrier-suitability design and support, and its knowledge of the Navy’s fighter and attack missions. Lockheed, which produces the Air Force F-117 stealth attack aircraft, offers its capabilities in prototyping and low-observable technology. And Boeing adds its avionics expertise; it already is developing advanced avionics for the F-22 and the RAH—66 Comanche next-generation attack helicopter. The Grumman team will put a high priority on transferring the avionics Boeing is developing for the F—22 and RAH-66 to the AX. “This will minimize costs and promote commonality between the AX and the F-22,” Ken Cannestra, president of Lockheed‘s Aeronautical Systems Group, said.

LTV was the first company McDonnell Douglas contacted to discuss a possible partnership, and their mutual expectations were so complementary that LTV served as McDonnell Douglas’ standard when it subsequently explored possible alliances with other contractors, including Grumman, Northrop and Rockwell. “From the outset, they understood we wanted to be prime and we understood they wanted to be a principal subcontractor,” Restelli said.

McDonnell Douglas, whose F-4 was the Navy’s primary carrier-based multimission combat aircraft before the introduction of the F-14, was attracted to

LTV’s knowledge of carrier suitability; the carrier-based A-7 attack aircraft is an LTV product. McDonnell also liked LTV’s experience in low-observable technologies and building large complex structures— LTV builds the intermediate sections of the B-2—its low-cost production techniques and the company’s orientation to advanced integrated product definition.

McDonnell Douglas is not overly concerned with the fact that LTV’s aerospace and defense unit is for sale. Nonetheless, the two companies have

an understanding that if the business unit is sold to a buyer who does not want to pursue the AX contract or wants to take a fundamentally different approach to the AX program, then McDonnell Douglas can leave the partnership with no strings attached, Restelli said.