An Early Look at ICBM Mobility

In response, the air force proposed sizing the initial Minuteman force at 150

missiles deployed in underground, hardened launch facilities at one base. The air force

further upped the ante to 445 missiles at three bases by January 1965 and 800 Minutemen

at five bases by June 1965. These numbers dwarfed what the air force had planned for

Atlas and Titan deployments (eventually the air force deployed more than 1,000

Minuteman missiles, compared to only fifty-four Titan II missiles). Eventually, but not

until each service connected with a few more jabs, the Polaris and Minuteman supporters

saw that each system offered unique advantages. Nestled in its submarine, the shorter-

range Polaris was nearly invulnerable, and the Minuteman offered a cheap and sizeable

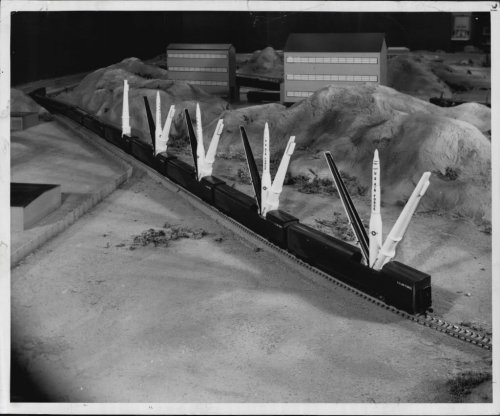

long-range attack force. To counter the navy's claim that mobility made the Polaris a

superior weapon, the air force advertised how a train-based Minuteman was equally

invulnerable and played the civilian economy card by suggesting that a rail-mobile

Minuteman was a "heck of a good use for the poor old railway system."18

Through the summer of 1958, the air force organized its thoughts on Minuteman

deployment. The missile was a technological risk demanding new propulsion and

guidance technologies, and it needed lighter nuclear weapons than those used for Atlas

and Titan. It was also a direct competitor for budget dollars with these programs. The air

force evaluated various force-mix schemes, and the two dominant positions that emerged

placed the Minuteman in hardened, dispersed, underground launch facilities and on a

train. Colonel Ed Hall did not favor mobility because he felt it would dramatically

increase costs, thus putting the overall program at risk, which was a viable concern in the

middle of efforts to develop multiple liquid-fueled missiles capable of launching heavier

warheads than the Minuteman. Hall found himself outgunned by Generals Thomas S.

Power, now the SAC commander, and Schriever. Power, a pilot whose command was

the ultimate user of the missile, believed that the deception afforded through mobility,

was an important military asset. Schriever, in charge of all air force ICBMs, balanced the

heavier throw-weight of the big liquid-fueled missiles against the unproven Minuteman.

Power asked AFBMD to study mobility, and on September 9, 1958, Schriever ordered a

joint AFBMD-SAC committee to study the issue.19

Power and Schriever wanted to know if Atlas, Titan, or Minuteman could become

a mobile system, and their investigators produced two reports, one on Minuteman and the

other on Atlas and Titan. The Minuteman study group was SAC-heavy with five of the

eight active members (the ninth member was an alternate) coming from SAC. In October

1958, they issued the first report, on Minuteman, and followed in December with the

report on Atlas and Titan. The Minuteman report considered force size, hardness,

dispersal, fast reaction, deception through decoys, and mobility. The only investigated

mode of movement was by train. Having discussed the problem with the president of the

Burlington Northern railroad and concluding that the railroads would support the air

force, Schriever, sensitive to the economic woes of a railroad industry facing stiff

competition from personal automobiles, trucking, and air transportation, believed the

railroads would be eager to participate, and he was right. Demonstrating himself to be an

adroit gatherer of support,-Schriever surmised that because a rail system was important to

the national economy, linking Minuteman to the railroads would unite the system "with

an essential national industry possessing a powerful lobby and a commitment of

government support." This strategy proved effective, for a while.20

The air force had previously studied barges and trucks as ways to mobilize its

ICBMs and concluded that barges were unsatisfactory because lakes and rivers did not

provide sufficient space for the planned force and were too close to population centers.

Truck-based systems were too expensive, no doubt, because of the cost and complexities

of moving a 65,000-pound missile by highway. Railroads offered a wonderful economic

advantage because private industry had already built them, which meant they existed at

no cost to the air force; moreover, private corporations also maintained the national

railroad infrastructure. All the air force had to do was build the railcars to contain the

weapon system and provide the crews to control it, but private railroad crews and their

locomotives could operate the train. Railroads also possessed expertise in moving heavy

and bulky objects and were in business to deliver goods undamaged to their customers.

Unlike the navy, which had to buy and build its own transportation network, the air force

could rent services at a cheaper cost than that required to operate and maintain a

submarine fleet. A railroad-based system eradicated the truck convoys previously needed

to support a mobile missile and virtually eliminated the cost of developing a

transportation system to move the missile. Trains were a simple and elegant solution to a

demanding problem.

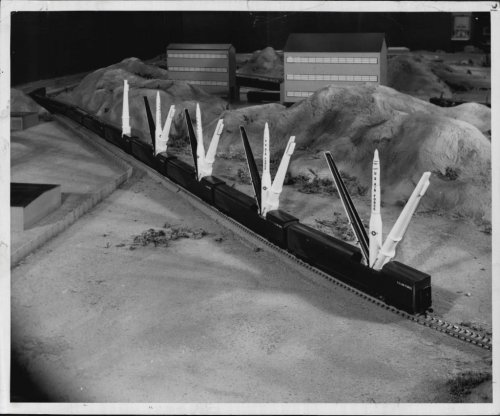

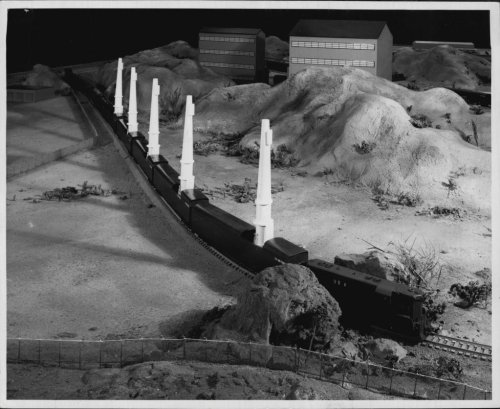

The investigators made a number of assumptions, a necessity given the near-daily

changing force size and composition of the ICBM program. Assuming a 1963 total force

size of 1,200 Minuteman missiles and cooperation of the railroads, the study assumed

that a quarter of the force, 300 missiles, would be rail mobile. Originally, one train,

called a mobile missile task force, contained three missiles and operated over 600 miles

of track with task force support centers located at existing air force bases. For a force of

300 missiles, 100 trains were required, and the investigators optimized each train's

operational trackage at 600 miles. The air force changed these numbers over the ensuing

years, but fewer trains meant that the remaining task forces had more miles of track to

roll over.21

Imagine a line of railroad track. According to the air force study, using two

pounds per square inch of atmospheric overpressure as the amount needed to destroy a

mobile Minuteman train of three missiles operating over 600 miles of track, the Soviets

required thirty reentry vehicles delivered down the rail line (if they knew which ones to

hit) to ensure the destruction of one train. Based on an assumed Soviet CEP of two

nautical miles and a five-megaton warhead's radius of destruction, this forced the Soviets

into an uneconomical kill ratio of ten to one; that is, the Soviets had to expend ten

warheads for every one American Minuteman. Destroying the mobile Minuteman was an

expensive problem for the Soviet Union because it required a minimum of thirty Soviet

missiles to destroy one Minuteman train, adding up to 3,000 perfectly working Soviet

missiles to destroy the entire mobile force of 300 Minuteman missiles, which did not take

into account the underground-based Minuteman force of 900 missiles. By using trains,

the air force could address all of the Bacher Panel's recommendations with one system;

moreover, a mobile system effectively eliminated any Soviet numerical advantage with

fewer American weapons.22

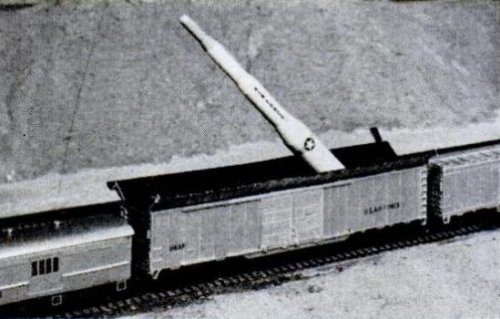

Putting the Minuteman on a train was not exactly simple. The cars containing the

missiles had to protect delicate missile components including the guidance system and

solid propellant by providing an environmentally controlled, air-conditioned, shock-free

environment that minimized vibrations. The missile needed a controlled temperature

range of eighty degrees plus or minus twenty degrees to protect its electronics from heat

and humidity, and shock isolation was required because vibrations could crack the

missile propellant. Solid propellants are liquids when poured; they dry hard inside the

casing of the missile stage. Shock and vibration can crack the solidified propellant,

which leads to uneven motor performance or forces chunks of unburned propellant

through the nozzles and throat assemblies, which could cause in-flight failure.23

When launching, three fast-reacting, hydraulic leveling jacks lowered to stabilize

the car before erecting the missile. Additionally, the missile car provided an erecting

mechanism to raise the missile to a vertical position for launch and rotated the missile to

the required prelaunch azimuth for accurate guidance. Building a flame deflector into the

launch car's bottom prevented exhaust gas damage to the railroad right-of-way and thus

permitted the train to move quickly after the missile launch. Because a railroad car

typically handled up to forty tons, the Minuteman's heft posed no serious problem. By

1960, a pre-prototype missile car existed, and in January 1961, American Car and

Foundry of Berwick, Pennsylvania, built the first prototype Minuteman launch car at a

cost of one million dollars. Painted air force blue, the car traveled across America by rail

to the Boeing Company in Seattle, Washington, where Boeing's engineers completed the

interior outfitting of the eighty-five foot-long, ten-foot wide, fifteen-foot-high rail car that

was no larger than the standard passenger car of the previous thirty years.24

The committee proposed thirteen units in the train, including one diesel

locomotive, a fuel tank car for the locomotive, a generator car, a water car, a Pullman

sleeper, a diner car, a control car, three missile cars, one missile support car, a generalpurpose

support car, and a caboose. The train's composition varied over the next three

years as the number of missiles per train varied between three and six. The air force

made allowances for variations in the support cars as well, but the study established the

basic pattern. The committee made no recommendations as to special requirements for

the railroad-provided locomotive, although one would expect that locomotives hauling

nuclear weapons, a national asset, through remote areas would have to meet higher

standards of reliability and maintenance than generic freight engines.25

The missile support car contained checkout equipment and general maintenance

supplies, while the general support car contained a jeep or truck and routine supplies.

The control car was the nerve center of the air force mission, holding the command and

control electronics, communication systems to receive launch orders from higher

authority, and a small armory for defense. The caboose, required by Interstate Commerce

Commission regulations, was home to the civilian train crew of five to fifteen personnel.

Federal regulations required five crewmen, but the air force estimated as many as fifteen

might be required, and the total personnel assigned to a task force was set at twenty-two.

This included the five-member civilian train crew, one air force task force commander,

three controllers, three communications technicians, two dining stewards, two custodians,

three maintenance and checkout specialists (one per missile), two refrigeration and

heating specialists, and an administrative clerk. The air force desired three eight-hour

shifts each day. During a typical month, a Minuteman train crew would have spent

fourteen days on the rails, seven days on rest status, and nine days completing

assignments at their home base. The average crewmember could expect to be away from

home at least six months out of the year.26

The study group developed five concepts of operation, designated "A" through

"E" that varied the balance between train movement, launch reaction time, and ease of

operation. Efforts were made to balance the need to move the missiles frequently enough

to avoid detection and the need to stop the train to launch the missiles. Complicating

matters was that the Minuteman train had to contend with the routine traffic of the

railroad, and to be a good partner, the air force could not dominate the nation's rail

system. The missiles required known launch site coordinates in their guidance systems

before liftoff; thus, to minimize reaction time upon receipt of a launch order, this meant a

train had to remain close to a previously surveyed launch site.

________________________

18 Unnamed air force personnel quoted in "U.S. Likely to Make Solid-Fuel Missiles Key Defense

by '65," New York Times, June 15, 1958, 24. The Minuteman force structure data is from Neufeld,

Ballistic Missiles, 229. Divine, The Sputnik Challenge, 115-127, details budgeting and liquid-fuel missile

force structure changes resulting from worries over the missile gap

19Neal, Ace in the Hole, 92-97; Byrd, Rail-Based Missiles, xi. See also Reed, "U.S. Defense

Policy," 56-71.

20Advanced Planning Office, Deputy Commander Ballistic Missiles, Air Force Ballistic Missile

Division, "Future for Ballistic Missiles, November 1959, Revised January 1960," slide 27, unaccessioned,

declassified document. BMO document 02056295, file 13J-4-4-13, AFHRA. Byrd, Rail-Based Missiles,

13; Quote from Frederick J. Shaw and Richard W. Sirmons, "On Steel Wheels: The Railroad Mobile

Minuteman," SAC Monograph No. 216 (Offutt Air Force Base, NE: Office of the Historian, Strategic Air

Command, 1986), 5. Declassified historical monograph excerpt, IRIS no. K416.01-216, AFHRA.

21SAC/AFBMD, "Minuteman Mobility Concept Report, October 1958," 10-12, unaccessioned,

unclassified collections. BMO box M-1, AFHRA.

22Ibid., 12. Calculations involving target destruction and missile survivability are complex and

time consuming. Changes to force sizes and mixtures meant that analysts had to recompute these values.

A brief discussion may be found in Robert D. Bowers, "Fundamental Equations of Force Survival," in

Kenneth F. Gantz, The United States Air Force Report on Ballistic Missiles (New York: Doubleday and

Company, Inc., 1958), 249-260. See also James Baar, "Hard-based Minutemen vs. Mobility," Missiles

and Rockets 7 (October 17, 1960), 24.

23SAC/AFBMD, Minuteman Mobility Report, 16, 20-21.

24Appearance of missile car from "Transportation Depot Maintenance Division Estimated Cost for

Construction of Mobile Missile Train (S-70-61), Utah General Depot, U.S. Army, Ogden Utah, 1960,

unaccessioned, unclassified collections. BMO box M-22, AFHRA. Information on construction and

outfitting of missile car from "New $1,000,000 Freight Car Launches Missiles," New York Times, January

26, 1961, 37.

26Ibid., 16-19, 57. See also Space Technology Laboratories, "Mobile Weapon System Design

Criteria, WS 133A-M (Minuteman), May 19, 1960, 4-6, unaccessioned, unclassified collections. BMO box

M-1, AFHRA. The design criteria, submitted by Dr. R. R. Bennett, the Minuteman Program Director of

Space Technology Laboratories, an offshoot of Ramo-Woodlridge, won air force approval from Colonel

Samuel C. Phillips, the air force Minuteman program director. Phillips had a distinguished air force career

that included service as the Apollo program manager after the disastrous 1967 Apollo 1 fire.