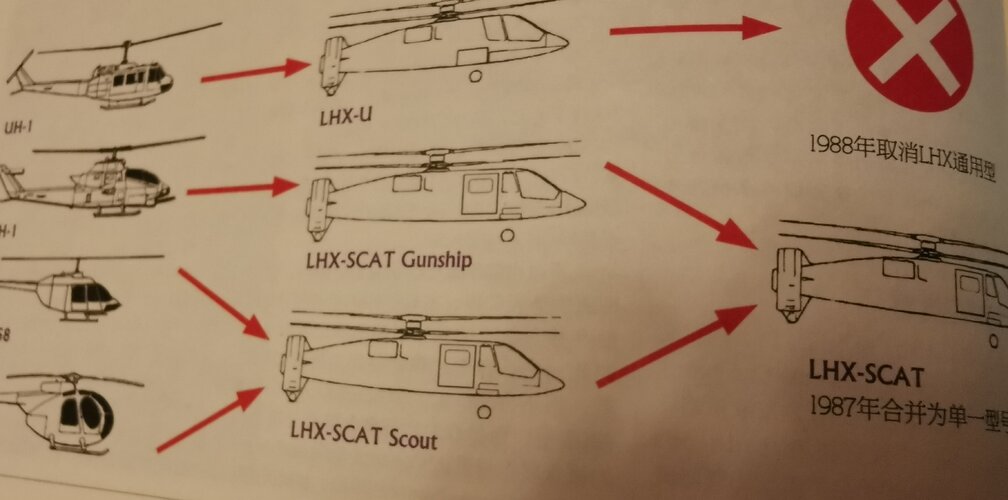

In LHX the revised specifications gave no credit for anything exceeding what a conventional helicopter could do, no matter how good or little extra it might cost.

Never underestimate the human side of the equation. The Army Aviators at the time were very much disinclined toward anything different. They were concerned with the risks associated with the new technologies and the potential for delays because of this. As mentioned it was the height of the cold war, so they wanted something fast. Also recall originally they wanted something very light. The Aviators were mostly Vietnam veterans who expected scout aircraft to be lost at a significant rate, so they wanted relatively simple as well. Rather ironic that over time ALL of the original logic for LHX went out the window.

Army aviators were the ones who pushed for the original specifications, concerned about vulnerability of conventional helos, the large area they would have to cover in Europe and elsewhere, and expected future threats. Also given the limited numbers of vehicles that could be available ar a given place at a given time, they felt the need for more than what a regular 'coper of the time could do. One other benefit was that Congress, seeing this as a chance to advance American VTOL technology relative to what was coning up in Europe and elsewhere, was very supportive of the LHX program. The sudden dumbing down after all the encouragement by the Army to industry for advanced capabilities caught almost everyone flat-footed. Congress felt it had been subjected to a bait and switch and support went from advocacy to skepticism, something the program never overcame and one of the sources of the sniping against RAH-66, which of course did have delays that weren't so well tolerated because it really wasn't that much of a push airframe-wise.

Now since you wondered what I thought happened (you did wonder, didn't you?), I'm a bit of a cynic about this. There definitely were some cautious people at the top of the Army, but I'm of the opinion there was more. Because of some screwups with teh way things were awarded, especially some of the sole-source stuff done during the war, the mantra was maximum competition. It got to the point that competition became not nearly a means to an end, but an end in itself. Now at the time, there were really only two companies that had experience with a technology that had a reasonably low risk chance of delivering, Bell and Boeing. Bell was one with Tilt-Rotor, and the other was Boeing, who was also

considering a Tilt-Rotor. That in and of itself meant there wouldn't be that much competition, given the multiple manufacturers there were then. What made the situation worse was what if the two companies teamed like they did on JVX? Even if they were the best choice, there wouldn't be "competition", and that might be considered unacceptable. Also, what the Army was asking for might be viewed by USAF as infringing on their "roles and missions" and they'd start lobbying against it (a concern I have for FLRAA if it goes forward), something Army definitely didn't want given how much they wanted to replace the OH-58.. So, in order to preserve the chance they'd get

something they lowered the requirements to what a conventional helicopter could do and insured that a higher performance aircraft had no chance. Ironically, they ended up allowing Comanche more weight and power than what they directed in the solicitation.

So here we are, four failed attempts to replace the OH-58 later, still not having anything to show for it.

Or so my twisted logic goes.