TheKutKu

ACCESS: Secret

- Joined

- 13 February 2023

- Messages

- 464

- Reaction score

- 1,385

These aren't particularly "new", I'm sure the people around here know about it and I've seen it mentionned occasionaly in various french sites , but it's quite little known now that I think of it.

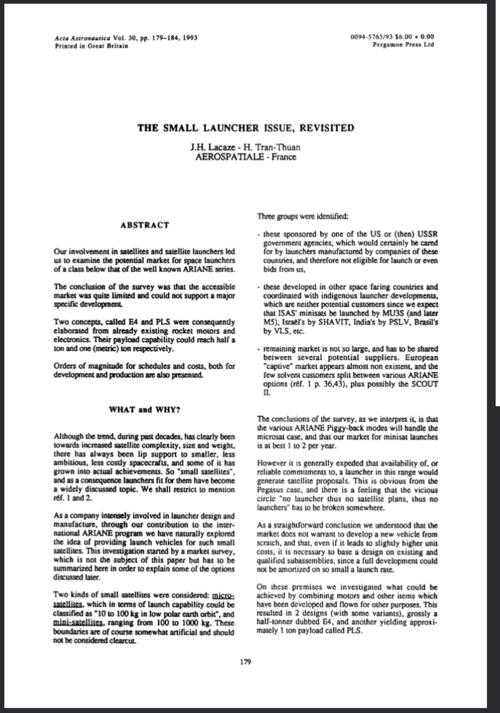

The idea to use SLBM and IRBM stages for french orbital launchers didn't die in the early 70s and resurfaced in the 80s and 90s.

http://www.anciensonera.fr/sites/default/files/fichiers%20pdf/Bulletin_AAO_Hors-Serie-Espace.pdf not an unknown link on this site, I'm going to at least provide a translation of this unselectable text

WHEN FRANCE WANTED TO CONVERT ITS MISSILES INTO LAUNCHERS

For more than 40 years, the French space industry has been manufacturing ballistic missiles for nuclear deterrence, and has considered their possible conversion into space launchers. Although the idea has been attractive for reducing costs, none of these projects has materialized.

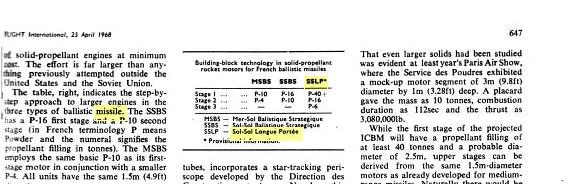

In the 1960s, the Pierres Précieuses program provided France with a space capability with the Diamant A launcher. This is the civilian result of a family of military demonstrators which allow the mastery of the technologies necessary for the much more discreet development of two families of missiles for nuclear deterrence: the ICBM (Strategic Ground-to-Ground Ballistic Missiles) which will be deployed on the Plateau d'Albion from 1971 to 1998 and the SLBM (Strategic Sea-to-Ground Ballistic Missiles) which will enter into service on nuclear ballistic missile submarines (SNLE) also from 1971. With these strategic missiles, France will now have a range of mass-produced solid propellant engines that it would be a shame not to take advantage of.

DIAMANT'S SUCCESSOR

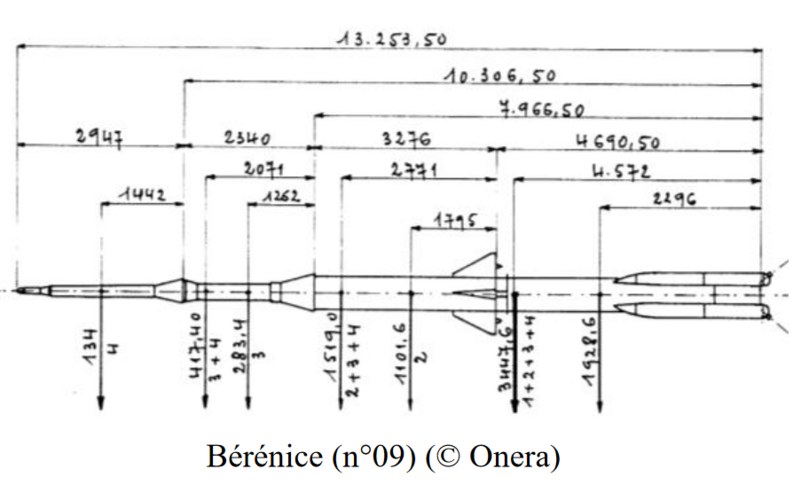

In fact, this idea began to interest pique the engineers of SEREB (Société d'étude et de Réalisation des Engins Balistique) well before the first flight of Diamant A. From June to October 1964, its first stage Emeraude had indeed failed three times during its first flight tests. The reasoning is then as follows: if this Emerald stage with liquid propellants is not available in time, perhaps it will be necessary to replace it by a stage with solid propellant P10 (for 10 tons of propellant). Under development, this stage would be used both as the 1st stage of the SLBM M1 and as the 2nd stage of the ICBM S2. However, the Emeraude had a series of successes in 1965 and found itself as the 1st stage of the Diamant A when it placed the first French satellite, Asterix or A1, into orbit on November 26.

To follow on this first generation of experimental launchers, a Super Diamant was studied. This time, the Emerald stage could be replaced by the P16 first stage of the S2 missile. With improved upper stages, it would be possible to multiply the satellite mass by three, from 80 to 250 kg. However, the P16 is not the only one in the running and it is in competition with a new liquid propellant stage, the Amethyste. In May 1967, it is the later which is chosen by the CNES - which had just recovered the responsibility for the program managed before by the DMA (Ministerial Delegation for Armament) - for the launcher Diamant B.

It was not until 1975 that a missile stage appeared on a Diamant, with the P4 2nd stage of the M1, which gave its name to the Diamant BP4 series. This series would have only three launchers before stopping, for lack of small satellites to launch.

THE REPLACEMENT OF EUROPA

At the beginning of 1966, while Diamant was triumphing, the ELDO (European Launcher Development Organisation), which was developing the Europa launcher, was in deep crisis and SEREB proposed a national alternative to the European program in difficulty. This Hyper Diamant would be realized by placing the two improved upper stages of the Super Diamant on the two stages P16 and P10 of a S2 missile. From the new space center planned in French Guiana, this architecture would make it possible to place 100 kg in geostationary transfer orbit. The crisis would finally be resolved and the break up of the ELDO postponed, but the Hyper Diamant would remain in the pipeline in a tri-stage form, with the two stages P16 and P10 surmounted by a P4.

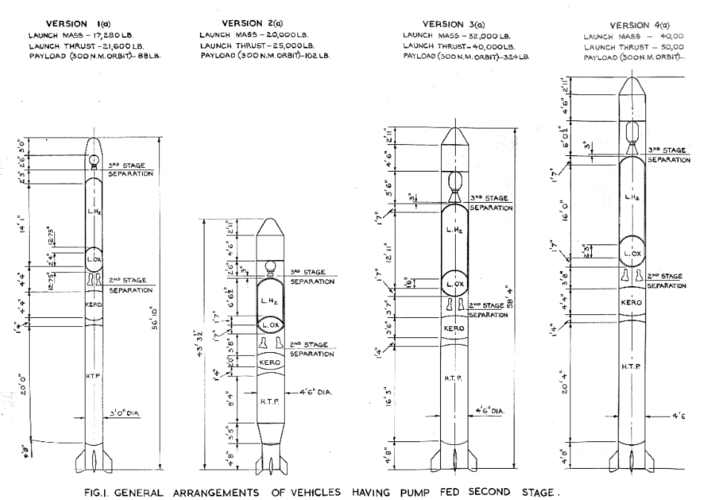

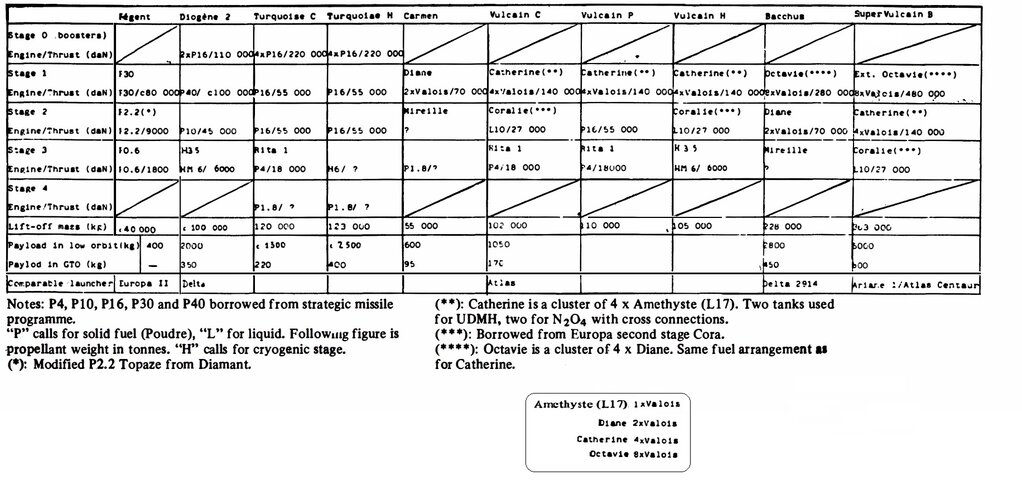

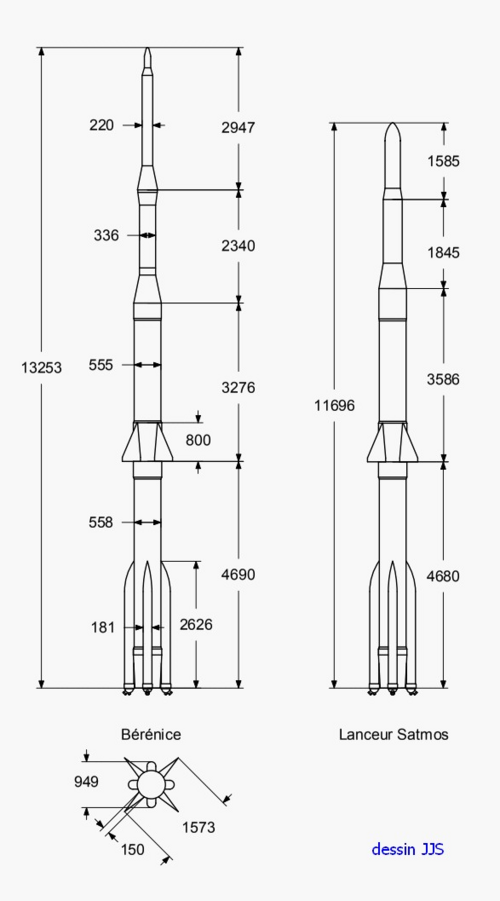

In July 1968, when the ELDO was again threatened, General De Gaulle accepted the idea of CNES to study alternatives to Europa 2 for the launch of the Franco-German Symphonie satellites. SEREB pushed its concept further with not only a launcher but a real family of modular launchers called Turquoise. It is a meccano using the P16 both as 1st and 2nd stage but also as lateral gas pedals. With a 3rd stage P4 and a perigee engine, it would be possible to place nearly 500 kg in geostationary transfer orbit, and by replacing this composite by a cryogenic stage one would even reach 800 kg.

After the fiasco of Europa, in 1971, this concept Turquoise would be finally forgotten to the benefit of Ariane, more evolutionary and easier to "sell" to the to the European partners. The satellites Symphonie satellites would be launched by the Americans (Delta rocket) who put as a condition the prohibition of any commercial use commercial use!

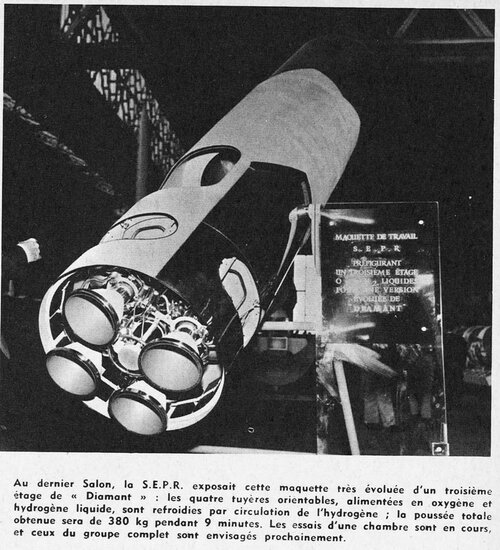

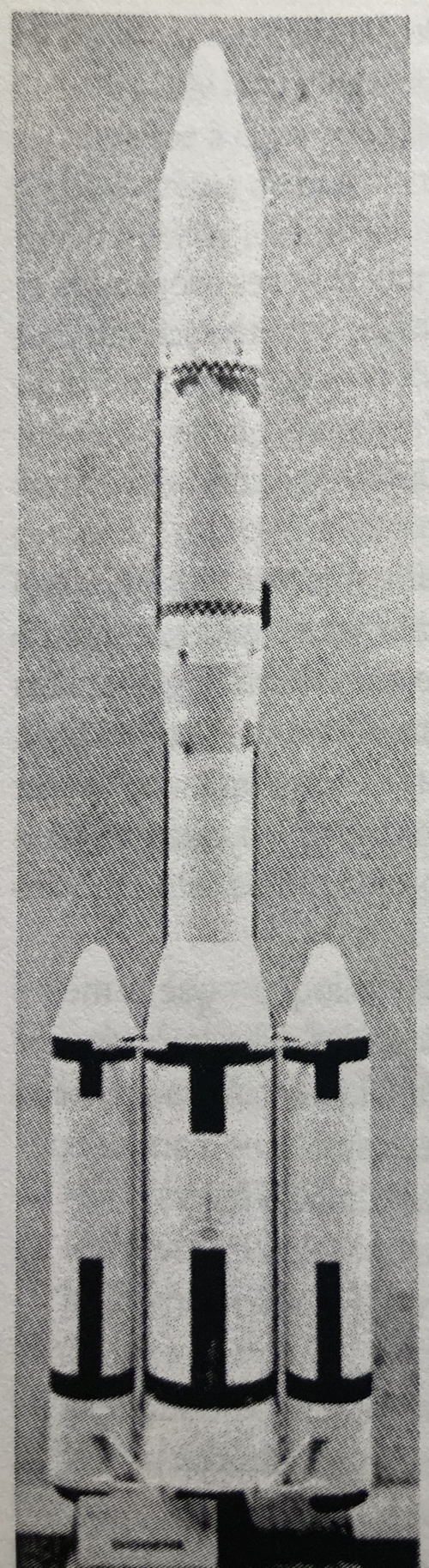

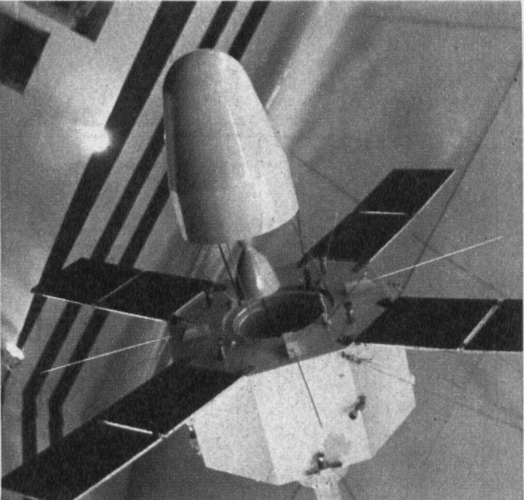

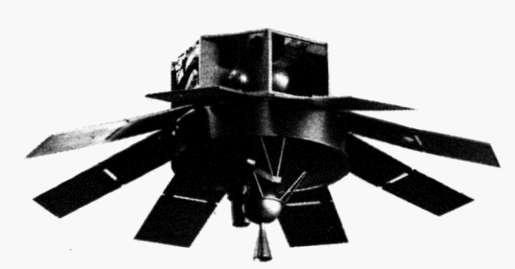

Model of Turquoise. It would be a modular orbital launcher based on missiles component in case of failure of the Europa Program.

THE RETURN OF SMALL SATELLITES

In 1989, fourteen years after the last Diamant BP4, the space industry had changed. The success of Ariane had propelled the Europeans and their industry to the forefront, but it had also opened access to space to private initiatives and a plethora of projects was announced. The miniaturization of electronics allowed a return of small scientific and military satellites to such an extent that a private firm started in 1988 the development of a small dedicated launcher, the Pegasus, the first new American launcher since the shuttle. In addition, France decided to acquire an optical spy satellite, Helios, which will be rapidly completed by small listening satellites. Missiles have also evolved, the S2 had been replaced by the S3, while the M2, the M20, the M4 and soon the M45 had replaced the M1.

M4 and soon the M45.

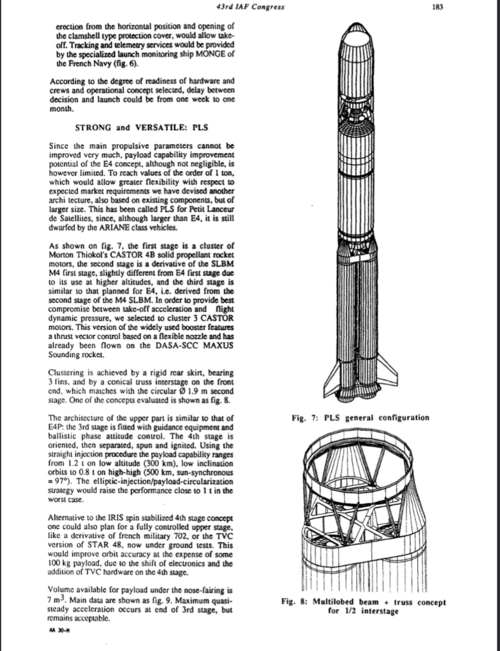

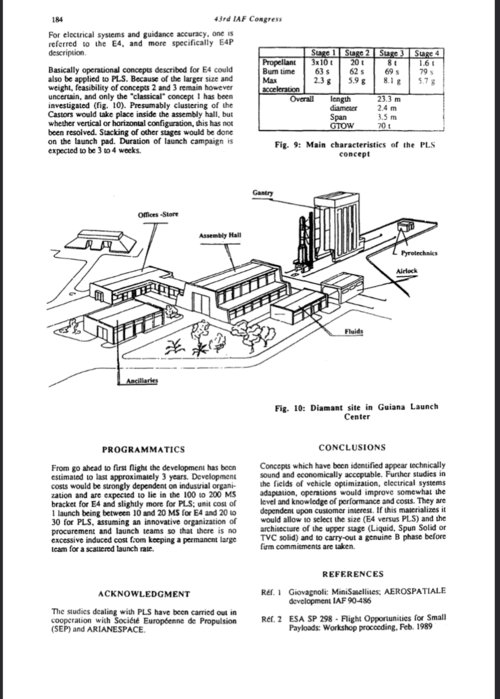

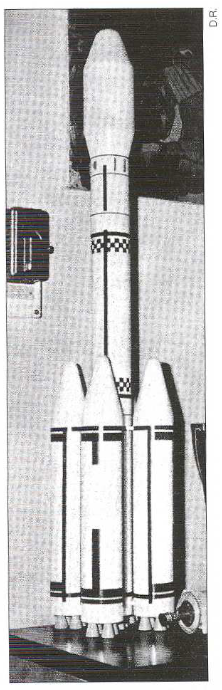

In 1989, Aerospatiale started a study on its own funds with the Société Européenne de Propulsion (SEP) and Arianespace for the development of a PLS (Petit Lanceur de Satellites, Small Satellite Launcher). The base idea is to reuse stages of the M4 at the end of their operational life to reduce costs thanks to already qualified material.

Nevertheless, a large stage is missing to ensure the takeoff and the Europeans must turn to the American technology, in this case the Castor 48 engines of Thiokol (which are also used as first stage for the European Maxus sounding rockets). A bundle of three Castor 4B would thus constitute the first stage P35, upon which would be stacked the two stages P20 and P8 stages of the M4. A small Italian IRIS powder stage (Italian Research Interim Stage), developed to launch small satellites from the Shuttle's payload bay, would provide precision orbital injection. '

A rehabilitation of the Diamant launch pad in Kourou is even envisaged. The target capability is 810 kg in sun-synchronous orbit' at 500 km altitude. A development in three years is proposed for 630 million francs at the time, but neither CNES nor the industrialists believe in the development of the small satellite market outside the United States and the PLS remains on the drawing boards.

In 1989, the PLS Study attempted to find a space use to the M4 missiles stages. But it highlighted the lack of large propulsive stage for a First stage

E4 and E5, MILITARY LAUNCHERS

In 1990, in the absence of an accessible commercial market, the Aerospatiale teams decided to continue their studies on the conversion of the M4 missiles at the end of their service life into a low-capacity launcher for the DGA (Délégation Générale pour l'Armement), the only potential customer considered as credible.

To realize this so-called E4 launcher, they propose to add to the two stages of the M4 a third stage of American origin, the Orion 50 of Hercules Aerospace, just qualified as the 2nd stage of the Pegasus winged launcher. Two options are available for the 4th stage: the E4P (P for powder) carries an Italian IRIS stage for power, while the E4L (L for liquid) offers a liquid propellant module for greater injection precision. From the Diamant launch pad in Kourou, the capacity in heliosynchronous orbit at 500 km would be 350 to 450 kg.

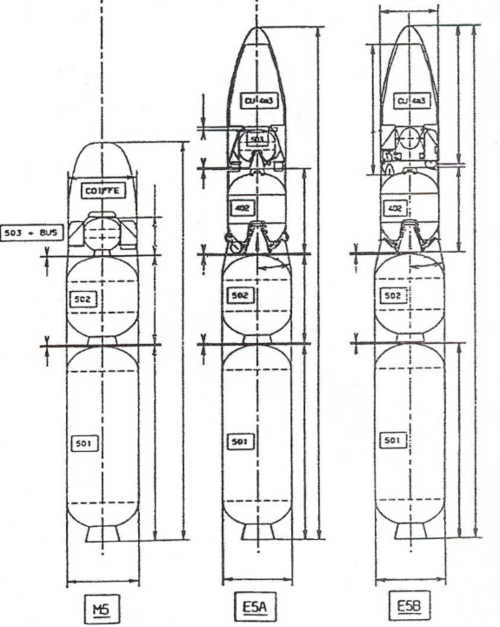

This logic is of interest to the DGA, which has asked Aerospatiale to include a preliminary design for a small E5 launcher in its study for the next generation of ICBM, the M5. Designed to make the most of the space available in the tubes of new-generation SSBN submarines, the M5 will also have a 20% wider diameter compared with the M4, and thus much more powerful stages, which makes it possible to consider a more powerful launcher that wouldn't need any foreign technology. The basic concept consists in adding the 2nd stage of the M4 (P8) on top of the two first stages of the M5 (501 and 502). The performances in SSO meet those of the PLS of 1989: 810 kg with an upper stage with powder (the 3rd stage of the M5), 550 kg with an injection module with liquid propellants.

The M5 missile (Left) and its potential space derivatives E5A and E5B. The fall of the USSR would result in budget cuts and only the M5 would be made under the name M51.

THE ANSWER IS ELSEWHERE

Interesting on paper, the E5 study highlights the limits of the concept. To make their detection more difficult, the missiles are designed for high short accelerations that would be dangerous for satellites. It is therefore out of the question to use standard MS stages: it is necessary to review their loading by using the same propellant as the Ariane 5 boosters. Moreover, the stages remain too small and offer few possibilities for evolution, except for the addition of lateral boosters. Finally, despite the simplification of all the electrical systems with existing equipment, such as the ring laser gyroscope units of the Tigre helicopter, the development bill remains dissuasive: 1.7 billion francs.

Two major events would change everything. First, in June 1990, the American phone manufacturer Motorola unveiled its Iridium project: 77 satellites of 315 kg in low orbit for mobile telephony. The reaction was not long in coming. In addition to competing projects (including Globalstar), Iridium generated the development of a multitude of small launchers around the world, attracted by the windfall that this new market promised to represent, and for which neither Ariane 4 nor the future Ariane 5, designed for geostationary orbit, were adapted. The other event was the collapse of the USSR and the end of the Cold War: this led to a downscaling in the M5 program - which nevertheless gave rise to the M51 missile - but above all opened the door to new technical cooperation with former enemies. François Calaque, then director of launchers at Aerospatiale, took stock of the situation. What Europe needs is not a converted missile, but launchers to complement Ariane 5, and this is a matter of urgency! There are two avenues to follow: the development in Europe of a civilian solid propellant stage of at least 50 metric tons, and the establishment of cooperation with the Russians on an intermediate launcher. The first would take nearly 10 years to come to fruition, with the adoption by ESA of the P80 program in 2000 (the first stage of the future small Vega launcher). The second would lead François Calaque to create Starsem in 1996, bringing together Europeans and Russians (Arianespace, EADS, the Russian space agency and the Samara space center or TsSKB-Progress) to commercially exploit the Soyuz launcher, just in time to win half of the Globalstar launches.

Stefan Barensky

The idea to use SLBM and IRBM stages for french orbital launchers didn't die in the early 70s and resurfaced in the 80s and 90s.

http://www.anciensonera.fr/sites/default/files/fichiers%20pdf/Bulletin_AAO_Hors-Serie-Espace.pdf not an unknown link on this site, I'm going to at least provide a translation of this unselectable text

WHEN FRANCE WANTED TO CONVERT ITS MISSILES INTO LAUNCHERS

For more than 40 years, the French space industry has been manufacturing ballistic missiles for nuclear deterrence, and has considered their possible conversion into space launchers. Although the idea has been attractive for reducing costs, none of these projects has materialized.

In the 1960s, the Pierres Précieuses program provided France with a space capability with the Diamant A launcher. This is the civilian result of a family of military demonstrators which allow the mastery of the technologies necessary for the much more discreet development of two families of missiles for nuclear deterrence: the ICBM (Strategic Ground-to-Ground Ballistic Missiles) which will be deployed on the Plateau d'Albion from 1971 to 1998 and the SLBM (Strategic Sea-to-Ground Ballistic Missiles) which will enter into service on nuclear ballistic missile submarines (SNLE) also from 1971. With these strategic missiles, France will now have a range of mass-produced solid propellant engines that it would be a shame not to take advantage of.

DIAMANT'S SUCCESSOR

In fact, this idea began to interest pique the engineers of SEREB (Société d'étude et de Réalisation des Engins Balistique) well before the first flight of Diamant A. From June to October 1964, its first stage Emeraude had indeed failed three times during its first flight tests. The reasoning is then as follows: if this Emerald stage with liquid propellants is not available in time, perhaps it will be necessary to replace it by a stage with solid propellant P10 (for 10 tons of propellant). Under development, this stage would be used both as the 1st stage of the SLBM M1 and as the 2nd stage of the ICBM S2. However, the Emeraude had a series of successes in 1965 and found itself as the 1st stage of the Diamant A when it placed the first French satellite, Asterix or A1, into orbit on November 26.

To follow on this first generation of experimental launchers, a Super Diamant was studied. This time, the Emerald stage could be replaced by the P16 first stage of the S2 missile. With improved upper stages, it would be possible to multiply the satellite mass by three, from 80 to 250 kg. However, the P16 is not the only one in the running and it is in competition with a new liquid propellant stage, the Amethyste. In May 1967, it is the later which is chosen by the CNES - which had just recovered the responsibility for the program managed before by the DMA (Ministerial Delegation for Armament) - for the launcher Diamant B.

It was not until 1975 that a missile stage appeared on a Diamant, with the P4 2nd stage of the M1, which gave its name to the Diamant BP4 series. This series would have only three launchers before stopping, for lack of small satellites to launch.

THE REPLACEMENT OF EUROPA

At the beginning of 1966, while Diamant was triumphing, the ELDO (European Launcher Development Organisation), which was developing the Europa launcher, was in deep crisis and SEREB proposed a national alternative to the European program in difficulty. This Hyper Diamant would be realized by placing the two improved upper stages of the Super Diamant on the two stages P16 and P10 of a S2 missile. From the new space center planned in French Guiana, this architecture would make it possible to place 100 kg in geostationary transfer orbit. The crisis would finally be resolved and the break up of the ELDO postponed, but the Hyper Diamant would remain in the pipeline in a tri-stage form, with the two stages P16 and P10 surmounted by a P4.

In July 1968, when the ELDO was again threatened, General De Gaulle accepted the idea of CNES to study alternatives to Europa 2 for the launch of the Franco-German Symphonie satellites. SEREB pushed its concept further with not only a launcher but a real family of modular launchers called Turquoise. It is a meccano using the P16 both as 1st and 2nd stage but also as lateral gas pedals. With a 3rd stage P4 and a perigee engine, it would be possible to place nearly 500 kg in geostationary transfer orbit, and by replacing this composite by a cryogenic stage one would even reach 800 kg.

After the fiasco of Europa, in 1971, this concept Turquoise would be finally forgotten to the benefit of Ariane, more evolutionary and easier to "sell" to the to the European partners. The satellites Symphonie satellites would be launched by the Americans (Delta rocket) who put as a condition the prohibition of any commercial use commercial use!

Model of Turquoise. It would be a modular orbital launcher based on missiles component in case of failure of the Europa Program.

THE RETURN OF SMALL SATELLITES

In 1989, fourteen years after the last Diamant BP4, the space industry had changed. The success of Ariane had propelled the Europeans and their industry to the forefront, but it had also opened access to space to private initiatives and a plethora of projects was announced. The miniaturization of electronics allowed a return of small scientific and military satellites to such an extent that a private firm started in 1988 the development of a small dedicated launcher, the Pegasus, the first new American launcher since the shuttle. In addition, France decided to acquire an optical spy satellite, Helios, which will be rapidly completed by small listening satellites. Missiles have also evolved, the S2 had been replaced by the S3, while the M2, the M20, the M4 and soon the M45 had replaced the M1.

M4 and soon the M45.

In 1989, Aerospatiale started a study on its own funds with the Société Européenne de Propulsion (SEP) and Arianespace for the development of a PLS (Petit Lanceur de Satellites, Small Satellite Launcher). The base idea is to reuse stages of the M4 at the end of their operational life to reduce costs thanks to already qualified material.

Nevertheless, a large stage is missing to ensure the takeoff and the Europeans must turn to the American technology, in this case the Castor 48 engines of Thiokol (which are also used as first stage for the European Maxus sounding rockets). A bundle of three Castor 4B would thus constitute the first stage P35, upon which would be stacked the two stages P20 and P8 stages of the M4. A small Italian IRIS powder stage (Italian Research Interim Stage), developed to launch small satellites from the Shuttle's payload bay, would provide precision orbital injection. '

A rehabilitation of the Diamant launch pad in Kourou is even envisaged. The target capability is 810 kg in sun-synchronous orbit' at 500 km altitude. A development in three years is proposed for 630 million francs at the time, but neither CNES nor the industrialists believe in the development of the small satellite market outside the United States and the PLS remains on the drawing boards.

In 1989, the PLS Study attempted to find a space use to the M4 missiles stages. But it highlighted the lack of large propulsive stage for a First stage

E4 and E5, MILITARY LAUNCHERS

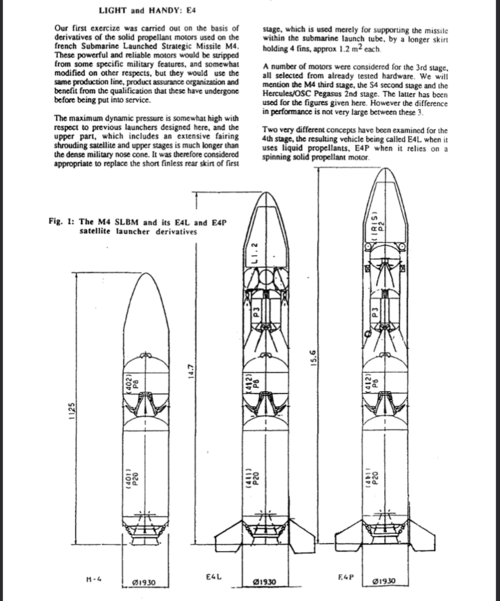

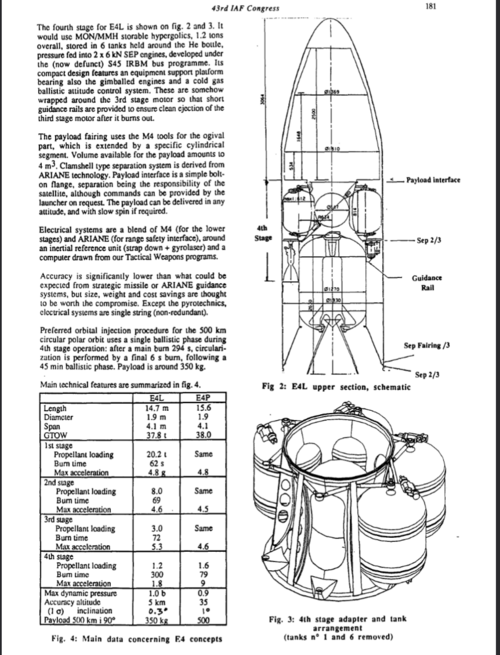

In 1990, in the absence of an accessible commercial market, the Aerospatiale teams decided to continue their studies on the conversion of the M4 missiles at the end of their service life into a low-capacity launcher for the DGA (Délégation Générale pour l'Armement), the only potential customer considered as credible.

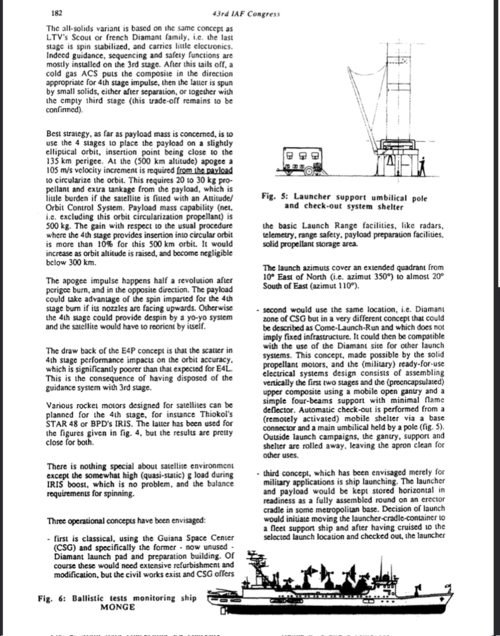

To realize this so-called E4 launcher, they propose to add to the two stages of the M4 a third stage of American origin, the Orion 50 of Hercules Aerospace, just qualified as the 2nd stage of the Pegasus winged launcher. Two options are available for the 4th stage: the E4P (P for powder) carries an Italian IRIS stage for power, while the E4L (L for liquid) offers a liquid propellant module for greater injection precision. From the Diamant launch pad in Kourou, the capacity in heliosynchronous orbit at 500 km would be 350 to 450 kg.

This logic is of interest to the DGA, which has asked Aerospatiale to include a preliminary design for a small E5 launcher in its study for the next generation of ICBM, the M5. Designed to make the most of the space available in the tubes of new-generation SSBN submarines, the M5 will also have a 20% wider diameter compared with the M4, and thus much more powerful stages, which makes it possible to consider a more powerful launcher that wouldn't need any foreign technology. The basic concept consists in adding the 2nd stage of the M4 (P8) on top of the two first stages of the M5 (501 and 502). The performances in SSO meet those of the PLS of 1989: 810 kg with an upper stage with powder (the 3rd stage of the M5), 550 kg with an injection module with liquid propellants.

The M5 missile (Left) and its potential space derivatives E5A and E5B. The fall of the USSR would result in budget cuts and only the M5 would be made under the name M51.

THE ANSWER IS ELSEWHERE

Interesting on paper, the E5 study highlights the limits of the concept. To make their detection more difficult, the missiles are designed for high short accelerations that would be dangerous for satellites. It is therefore out of the question to use standard MS stages: it is necessary to review their loading by using the same propellant as the Ariane 5 boosters. Moreover, the stages remain too small and offer few possibilities for evolution, except for the addition of lateral boosters. Finally, despite the simplification of all the electrical systems with existing equipment, such as the ring laser gyroscope units of the Tigre helicopter, the development bill remains dissuasive: 1.7 billion francs.

Two major events would change everything. First, in June 1990, the American phone manufacturer Motorola unveiled its Iridium project: 77 satellites of 315 kg in low orbit for mobile telephony. The reaction was not long in coming. In addition to competing projects (including Globalstar), Iridium generated the development of a multitude of small launchers around the world, attracted by the windfall that this new market promised to represent, and for which neither Ariane 4 nor the future Ariane 5, designed for geostationary orbit, were adapted. The other event was the collapse of the USSR and the end of the Cold War: this led to a downscaling in the M5 program - which nevertheless gave rise to the M51 missile - but above all opened the door to new technical cooperation with former enemies. François Calaque, then director of launchers at Aerospatiale, took stock of the situation. What Europe needs is not a converted missile, but launchers to complement Ariane 5, and this is a matter of urgency! There are two avenues to follow: the development in Europe of a civilian solid propellant stage of at least 50 metric tons, and the establishment of cooperation with the Russians on an intermediate launcher. The first would take nearly 10 years to come to fruition, with the adoption by ESA of the P80 program in 2000 (the first stage of the future small Vega launcher). The second would lead François Calaque to create Starsem in 1996, bringing together Europeans and Russians (Arianespace, EADS, the Russian space agency and the Samara space center or TsSKB-Progress) to commercially exploit the Soyuz launcher, just in time to win half of the Globalstar launches.

Stefan Barensky