Edinburgh's first line of defence

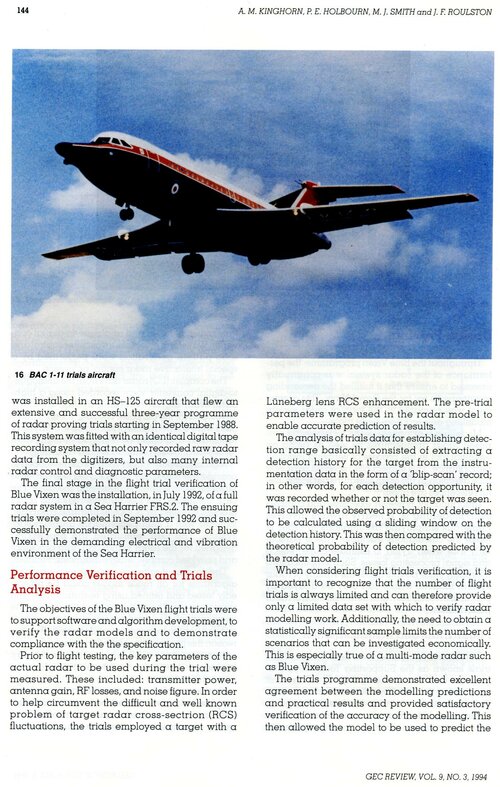

IT WAS the mid-1980s. The Berlin Wall had yet to fall. And the Royal Navy, determined after the Falklands War to improve the performance of its Sea Harrier - Britain’s home-bred fighter aircraft - was conducting an air-to-air combat exercise in the Australian desert.

By The Newsroom

23rd Jul 2004, 2:33am

The F-18, the Americans’ equivalent of the navy’s flier, was regarded by the US military as the superior plane. "A better airframe," as they put it. But the navy had recently asked British Aerospace, to upgrade the Sea Harrier’s air-to-air missiles. And to guide its launches they had commissioned and installed a radar system that was "technologically impossible" - or so said the Americans.

On hand in Australia to witness the improved Sea Harrier’s early trials were several top brass from the US military, and a number of their British counterparts. Eagerly awaiting the results back home, in Edinburgh, was the man who had designed that impossible radar - Professor John Roulston.

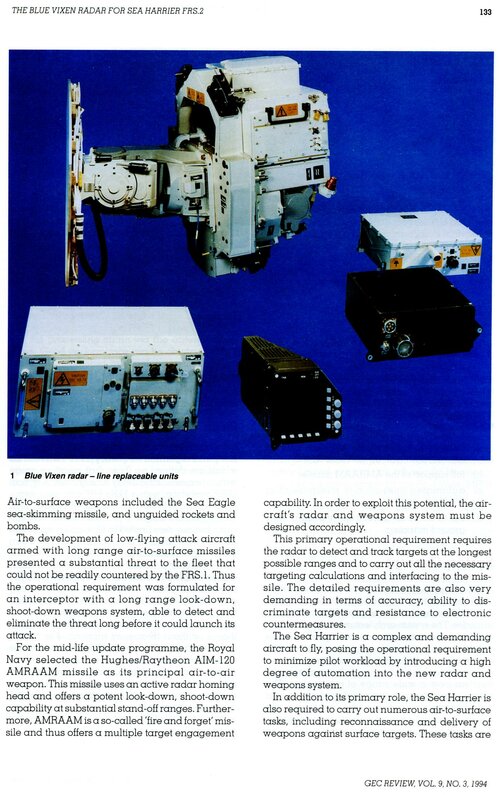

Flying against a swarm of F-18s, the Sea Harriers deployed their new missile and radar systems to devastating effect. The American planes were defeated time and time again. The exercise over, a US general conceded the Royal Navy’s new-found superiority. Lowering his field glasses, he announced his grudging admiration. "So it’s the poofy jet with the big stick," he drawled, to Roulston’s great delight.

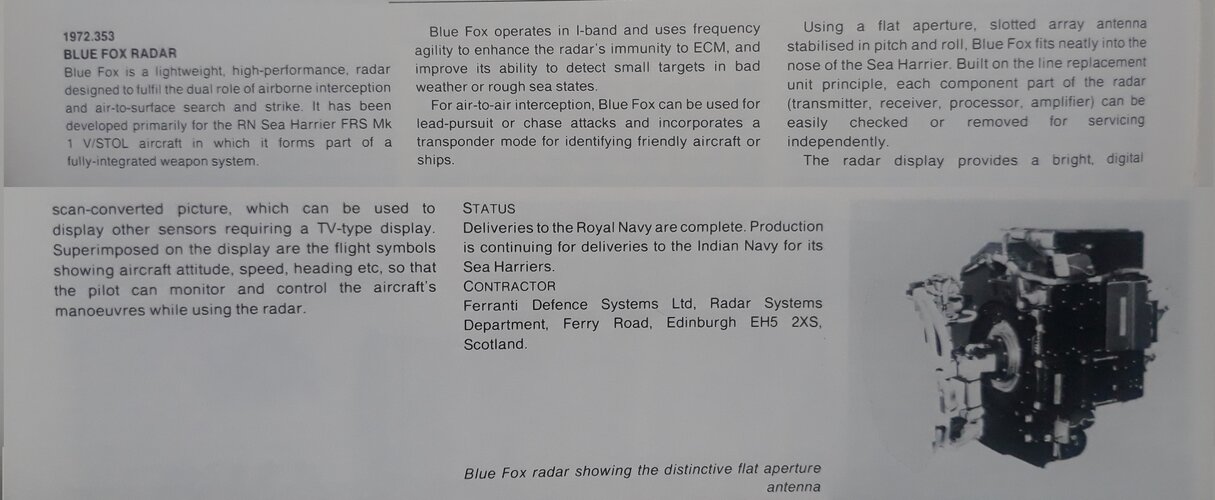

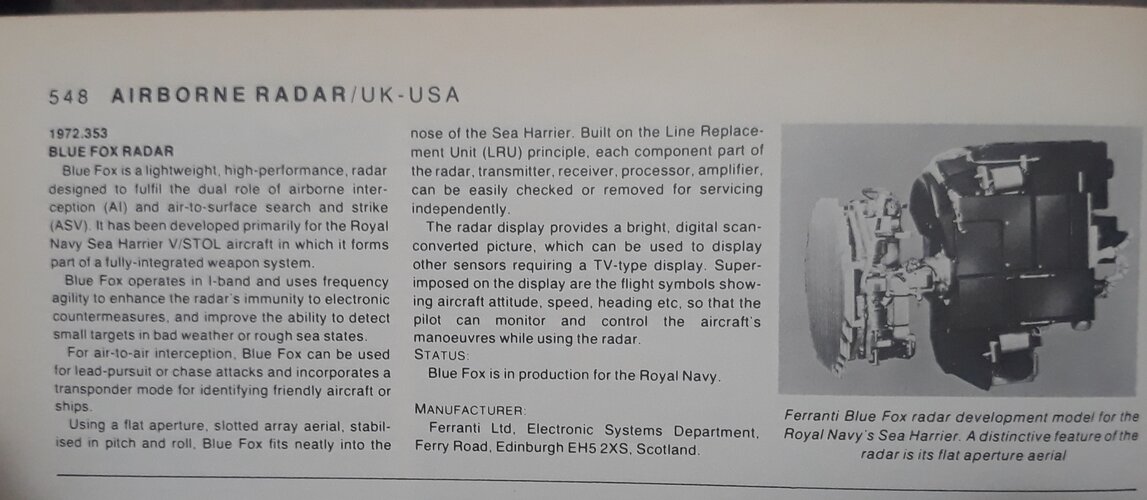

Roulston has spent the past 37 years living and working in Edinburgh, designing groundbreaking systems like the Blue Vixen radar in the Sea Harrier. One of the world’s top three radar experts, he has brought billions of pounds of business to Scotland since joining Ferranti, the electronics firm that is now part of BAE Systems. In September he will become chief executive of one of BAE’s core suppliers - Yorkshire-based Filtronics. But he will keep his home in Edinburgh, and says his new role will let him mastermind the next wave of technology needed to underpin BAE’s radars of the future - boosting its Scottish business.

Ferranti’s operation in Scotland dated back to the 1940s, and the nucleus of the post-war Scottish electronics industry. By the late 1960s it had become Edinburgh’s top defence sector employer. Roulston, attending university, saw two attractions of living and working in the capital in the summer of 1967.

There was the Festival, and there was a local girlfriend who happened to work at Ferranti.

Roulston wanted to work in hi-tech, and in those days that meant defence. Ferranti was not only the premier name, it also had several exciting sidelines including the first digi-TV for the London Stock Exchange, and high speed printing peripherals for computers - unheard of in those days.

"So I knocked on their door," says Roulston, "and at first they said, ‘We don’t take first-year students.’ But fortunately the HR officer in those days was a physicist. It wasn’t too difficult to draw him into a technical conversation..."

Awarded one of two placements, Roulston earned 9 that summer. He came back for the internship - and the Festival and his girlfriend - for the next two years. In 1970, he landed a full-time post after graduating, receiving an engineer’s starting salary of 1,300, with a possible bonus of 50.

By that time huge changes were afoot in the UK defence industry. The Wilson government had scrapped the TSR2 project - the last aircraft program that was truly British, rather than an international collaboration - in 1966. Ferranti had built a terrain-following radar for the TSR2, allowing it to fly "knap of the earth". But when the project was scrapped, the technology died with it. By the early 1970s Ferranti was looking to develop a new radar without any apparent hope of a contractor.

It lost out on the system for the GR4 Tornado after the Americans pressured the Germans to install a US-built radar- an early lesson, Roulston says, that political and commercial nouse would be as important as his engineering skills. There was more bad news to follow. With the second breed of Tornado, Ferranti was made 40 per cent subcontractor to Marconi - awarded the lead role by the government.

"The company drew me aside. They said: ‘We don’t want you involved in that project. The way to respond is with technology. Keep the good ideas to ourselves.’ And that’s how the Harrier came to be."

Roulston was asked to lead a small team of mathematicians and engineers to design a revolutionary new radar, based on research ideas concocted as early as 1973. The arrival of digital information and microprocessing had opened up huge opportunities to translate mathematical ideas into electronics. As late as 1981 the project was still without a contractor. But eventually it was bought by the Swedes for their Gripen. Then came the Sea Harrier.

"It was a period where engineering preceded everything," says Roulston. "It was an era before Cadbury, before corporate governance and shareholder interest. Every project went over budget, often by a factor of three. Ferranti was still a family business, just interested in engineering. When the Harrier opportunity came along, we were way ahead of Marconi. They had nothing to offer technologically."

Eventually Ferranti took over Marconi’s radar business. "But there is no point in looking back nostalgically at times past," Roulston stresses. "The competition comes in on budget these days and you’ve got to do the same. Let’s not forget the company hit a cash flow crisis and Wedgie Benn had to bail us out with 15m from the Labour government." The company floated, its shares recovered, and the government got its money back at a huge premium.

After the Sea Harrier’s success, Ferranti was ready for fresh opportunities, and Roulston turned his attention to the next great project already on the horizon in the 1980s: the Eurofighter. It was here he did some of his best work on the commercial side of the business, rather than in engineering. The radar contract won, Roulston began tackling the huge new challenges it created. "The risk was making it with European partners who’d never done that work before - to satisfy the political agenda - while still making a business out of it.

"So I focussed myself on learning to do business that way. Learning the languages, for example. We found the idiomatic nature of English got in the way. An engineer who was a little bit nervous in a presentation would use imaginative language rather than simplicity and repetition. He’d say, ‘Do you understand’, and everyone would nod. But later it would transpire that no-one had understood at all."

Once those problems were ironed out, "we began to respect the engineers we were working with - we realised there were very good engineers working outside the UK". Another skill was mastering the colossal length of the project cycle, and planning product obsolescence and development despite the fixed-price regime introduced under Margaret Thatcher.

"The Eurofighter bid pegged its prices in 1990 [when GEC took over Ferranti’s radar business]", Roulston explains. "I remember the business case I put forward to [GEC chairman Lord] Weinstock. I told him we’d be cash neutral in about 2015. And I think that’s still right. But when people heard me say it would take 25 years, they said I’d be out of a job. Well... they were wrong. Weinstock took the view that it was the price of being in the business. And he was right."

BAE, which later took over GEC’s radar business, got its production contract in 1998, and the first radar shipped in 2000. At 2m a piece, 120 have been sold to date. The Eurofighter order is expected to total 620 - about 1.25 billion of business.

It marked another huge leap in innovation. "We made a supreme product that took us into the next generation, which is what you’re always aiming to do," says Roulston. And true to form, Roulston has since been leading BAE’s "blue-sky thinking" for the next generation of radar, done in Edinburgh. The technology pioneered in the Eurofighter will take a new twist, with a transmitter located on one vehicle and the receiver on another. With covert communication it will be impossible to detect the radar is operating. BAE has already flown experiments with prototypes.

Roulston says he will keep two achievements at the front of his mind after he leaves BAE Systems. "Commercially, I think my peak was leading the Eurofighter consortium, particularly the concept of the Single Equivalent Company - the idea we’d better behave like an SEC, because our competitors, typically in the US, usually are. Meaning we had to get our efficiency to a point where we could compete. That single thought - a bit of homespun philosophy - has solved so many arguments!

"In engineering, the zenith for me was the Blue Vixen in the Sea Harrier. It looked technically impossible. It achieved world accolades. I don’t think I’ll better that."