You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Early Chinese aircraft.

- Thread starter blackkite

- Start date

bunnystar211

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 22 April 2019

- Messages

- 33

- Reaction score

- 42

thank you, I am making a name change.Dear bunnystar211, thank you a lot for your digest.

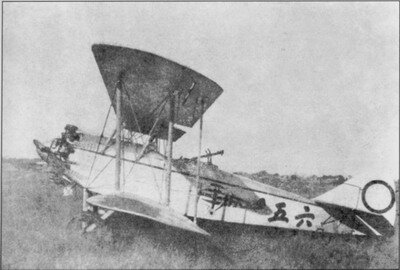

On the first photo there is Fong Yue-1, not two. Fong You (Feng Ru) has built two similar aircraft, No 1 and 2. The first one burned in hangar in 1910. Both were built in the USA, so I doubt they are "chinese aircraft". The No 2 airplane Fong Yue returned to China in February, 1911. 25 August, 1912, Fong Yue crashed during demonstration flight on this airplane and died.

I'm really doubt about year of Tangen seaplane, it looks too modern for 1910. Could you, please, give me the source

Is there any standard transcription rules for Chinese language, like Polivanov's rules for Japanese? The transcription of names in different sources differs drastically. FengRu = Fong Yu, Jia = Char (!), Yi seaplane = Yee seaplane, Chenggong = Chengkung, Geng = Keng and so on.

Sometimes it's difficult to recognize which aircraft is written about.

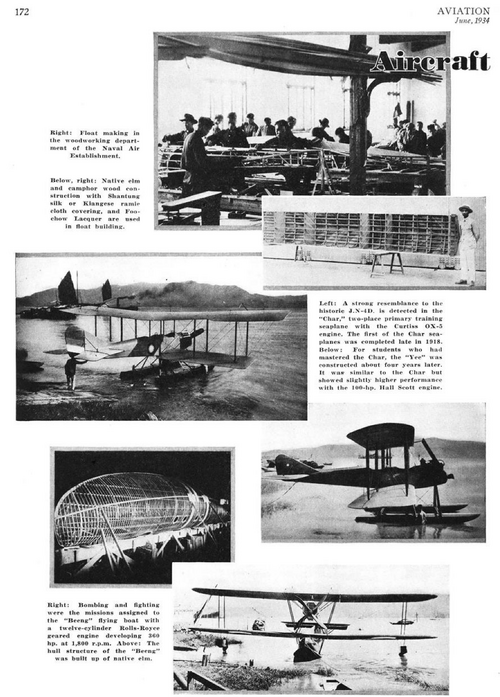

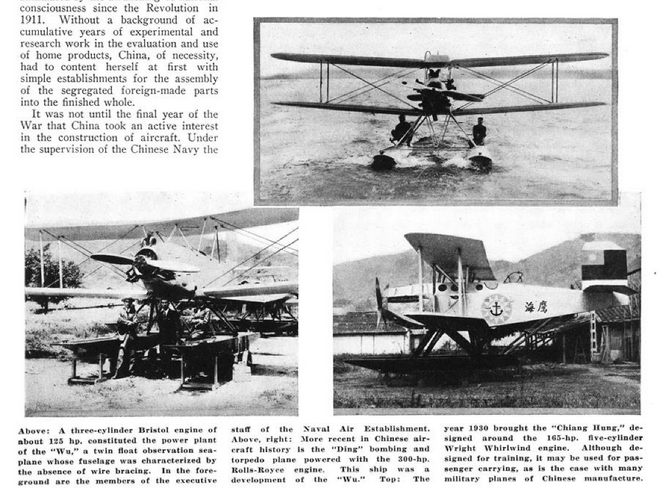

"River Crane" it seems the same as Fuzhou Chi-1 "Chiang Hung", but according to the article "Aircraft construction in the Сhinese Navy" (Flight, 1934, No. 10, pp. 211-214) it was built in 1930, not 1926. Is "1926" the correct date?

bunnystar211

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 22 April 2019

- Messages

- 33

- Reaction score

- 42

thank you, I am making a name change....we don't know Chinese language,so translate the four aircraft...

The four you are asking about hesham transliterate as:

羊城號 = Yangcheng series of trainers

-- https://daydaynews.cc/en/history/83430.html

中運 1 = Chungkuo 1 (China 1) transport aircraft, aka 'Loyalty 1'

-- https://www.secretprojects.co.uk/threads/chinese-transport-aircraft.7549/#post-65707

中運 2 Chungkuo 2 (China 2) transport aircraft, aka 'Loyalty 2'

-- https://www.secretprojects.co.uk/threads/chinese-transport-aircraft.7549/#post-65707

大公報號 Glider = Ta Kung Pao No.(?) 'advanced cabin glider'

-- I assume that these gliders were in some sponsored by the newspaper of the same name?

Challenges here also include 'romanizations' - contemporary Western sources would have used the Wade-Giles system - and random translations - like 'Sea Eagle' ('Hǎi yīng?).

bunnystar211

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 22 April 2019

- Messages

- 33

- Reaction score

- 42

If you have any suggestions, please put them forward, I'll watch each and everyone.

bunnystar211

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 22 April 2019

- Messages

- 33

- Reaction score

- 42

Thank you, Mawei Hsin-1 only built 1, named Ninghai No.2. I‘m checked the data this morning.I was a little dizzy at 1:00 am last night.It seems, only the second AB-3 (Ninghai, Hsin-1) was built in China in 1934. The first one was just bought from Japan. Or am I mistaken?

Attachments

bunnystar211

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 22 April 2019

- Messages

- 33

- Reaction score

- 42

bunnystar211

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 22 April 2019

- Messages

- 33

- Reaction score

- 42

I means Yang Ch'eng series, not just O2MC copy.Dear bunnystar211,

According to the book Andersson L. A History of Chinese Aviation. 2008 four copies of Avro 616 (similar to Avro 594) were built before 05.1933 in Shiukwan, they got names Yang Ch'eng 70 - 73,

I never heard about D.H.60G in China. Isn't it a mistake, and could you tell, when it was happen?

Thank you in advance.

River Owl = copy DH.60G Gipsy Moth + float.

bunnystar211

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 22 April 2019

- Messages

- 33

- Reaction score

- 42

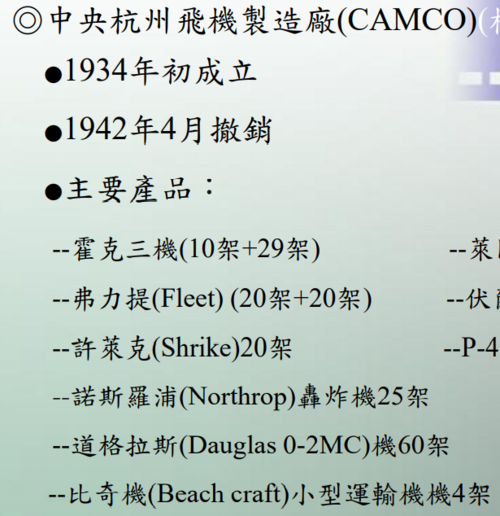

Data from AIDC in Taiwan today, Formerly known as China aircraft manufacturing. Not only Yang-Cheng O-2MC.Dauglas O-2MC series---60 built - isn't it a misprint? Other sources speaks only about 6 Douglas airplanes, five of them weared numbers Yang-Ch'eng 74 - 78 and were delivered by Shiukwan 03-07.1934

Last edited:

bunnystar211

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 22 April 2019

- Messages

- 33

- Reaction score

- 42

China not made I-16, but have a plan to build 100 number I-16. but it didn’t start. China just made 3+30 Chung 28A (seems like I-16) .Dear bunnystar211,

I didn't find in your list 293 Polikarpov I-16 and their variants built during 1939-1943 in State aircraft factory 600 (Urumchi), also in Kunming factory and CAF (Nanking)

bunnystar211

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 22 April 2019

- Messages

- 33

- Reaction score

- 42

bunnystar211

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 22 April 2019

- Messages

- 33

- Reaction score

- 42

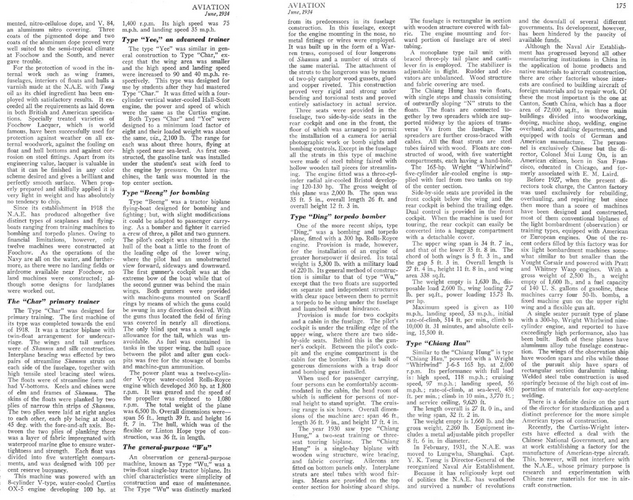

CAMCO

Dauglas O-2MC series---60 built

(O2MC-6 brand new)

(Douglas aircraft manufactured succeed)

Hawk II---?assembled/built?

(Hawk II in CAMCO)

(Hawk fighter made by CAMCO)

Hawk III---39 built(known:Curtiss Model 68C Hawk III)

(Hawk III is building)

Ryan ST series---20 assembled(known:Ryan STM2E and STM-2P)

Fleet series---40 built(known:Fleet 10 A/B)

(Fleet brand new 23/10/1935)

Ballanca 28-90B Flash---20 assembled & modified(equipped with machine gun and bomb rack)

Curtiss A-12 Shrike(Model 60A)---20 assembled

Northrop Light Bomber---25 built(known:Gamma 2EC)

(first Gamma left the factory, aircraft number 25)

Vultee V-11G---29 built

(first V-11G in the airport before its first fly)

Vultee V-12C---25 built

Vultee V-12D---3 built(Vultee order 52 aircraft, but CAMCO just build 3 aircraft, after transfer to India)

(HAL made V-12D for Chinese airforce in India )

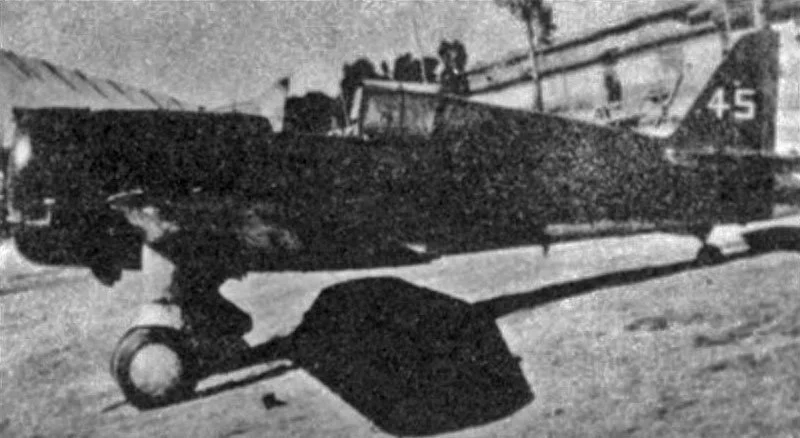

Curtiss H75M---30 assembled/built? (Chinese produced H75M max speed less 20km/h for engine assemble problems compare with made by Curtiss, but it was fixed by engineer at least one month later )

(Curtiss Hawk 75M in Airforce Officer School on Kunming, aircraft number 45)

View attachment 680839

(same plane, different perspectives, Chinese H75M is very specail, see the engine cowl)

View attachment 680840

Curtiss H75 A-5---? assembled(CAMCO order assemble 50 aircraft and equip it,but dont know how many has been assembled in CAMCO, after transfer to Hindustan)

(Hawk H 75A-5 left the factory in Lei Yun/Kunming)

(CAMCO Curtiss Hawk 75A-5, aircraft number 31)

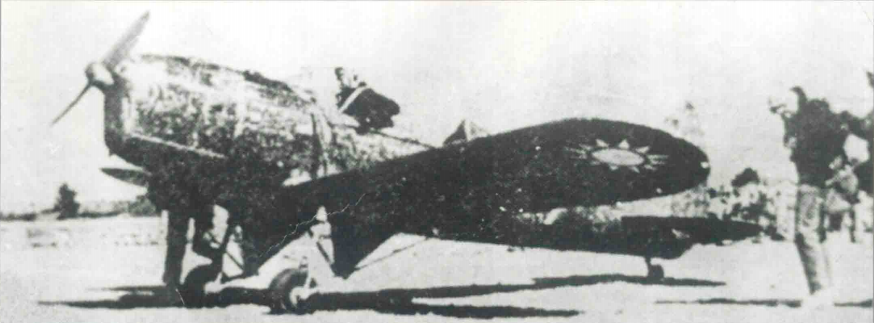

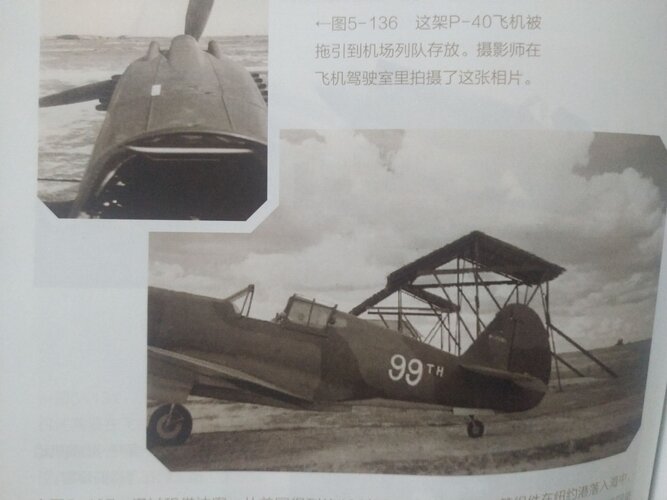

Curtiss P-40---99 assembled(known:H-81A2/3)

(finally a P-40 made by CAMCO, aircraft number 99TH, CAMCO assembled P-40 total 99.)

CW-21---1 modified & 2 built (China had 6 CW-21 aircraft in total, purchased 4 CW-21 from Curtiss, 2 CW-21 complete built)

purchased CW-21 registrations: NX19431/NX19941-NX19943. Among NX19431 is protoype, equip with 850hp engine, others 3 CW-21 equip with 1050hp engine. My edit the photo is Prototype NX19431.

Beach craft---4 assembled(Beach M-18R and weapons)

Dauglas O-2MC series---60 built

(O2MC-6 brand new)

(Douglas aircraft manufactured succeed)

Hawk II---?assembled/built?

(Hawk II in CAMCO)

(Hawk fighter made by CAMCO)

Hawk III---39 built(known:Curtiss Model 68C Hawk III)

(Hawk III is building)

Ryan ST series---20 assembled(known:Ryan STM2E and STM-2P)

Fleet series---40 built(known:Fleet 10 A/B)

(Fleet brand new 23/10/1935)

Ballanca 28-90B Flash---20 assembled & modified(equipped with machine gun and bomb rack)

Curtiss A-12 Shrike(Model 60A)---20 assembled

Northrop Light Bomber---25 built(known:Gamma 2EC)

(first Gamma left the factory, aircraft number 25)

Vultee V-11G---29 built

(first V-11G in the airport before its first fly)

Vultee V-12C---25 built

Vultee V-12D---3 built(Vultee order 52 aircraft, but CAMCO just build 3 aircraft, after transfer to India)

(HAL made V-12D for Chinese airforce in India )

Curtiss H75M---30 assembled/built? (Chinese produced H75M max speed less 20km/h for engine assemble problems compare with made by Curtiss, but it was fixed by engineer at least one month later )

(Curtiss Hawk 75M in Airforce Officer School on Kunming, aircraft number 45)

View attachment 680839

(same plane, different perspectives, Chinese H75M is very specail, see the engine cowl)

View attachment 680840

Curtiss H75 A-5---? assembled(CAMCO order assemble 50 aircraft and equip it,but dont know how many has been assembled in CAMCO, after transfer to Hindustan)

(Hawk H 75A-5 left the factory in Lei Yun/Kunming)

(CAMCO Curtiss Hawk 75A-5, aircraft number 31)

Curtiss P-40---99 assembled(known:H-81A2/3)

(finally a P-40 made by CAMCO, aircraft number 99TH, CAMCO assembled P-40 total 99.)

CW-21---1 modified & 2 built (China had 6 CW-21 aircraft in total, purchased 4 CW-21 from Curtiss, 2 CW-21 complete built)

purchased CW-21 registrations: NX19431/NX19941-NX19943. Among NX19431 is protoype, equip with 850hp engine, others 3 CW-21 equip with 1050hp engine. My edit the photo is Prototype NX19431.

Beach craft---4 assembled(Beach M-18R and weapons)

Last edited:

bunnystar211

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 22 April 2019

- Messages

- 33

- Reaction score

- 42

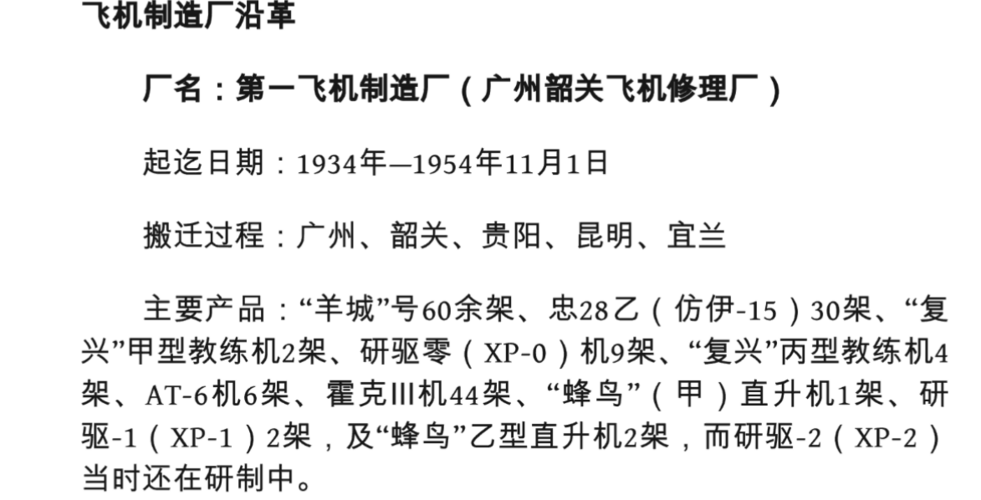

Guangzhou/Kunming 1st Aircraft Manufacturer

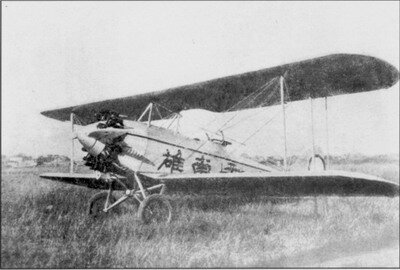

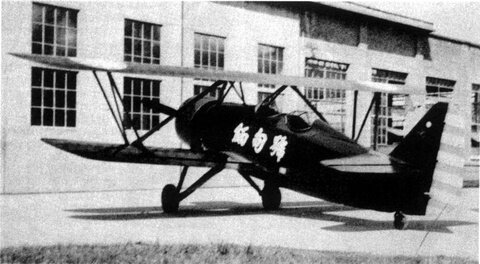

Yang Ch'eng(羊城號) series---60 built

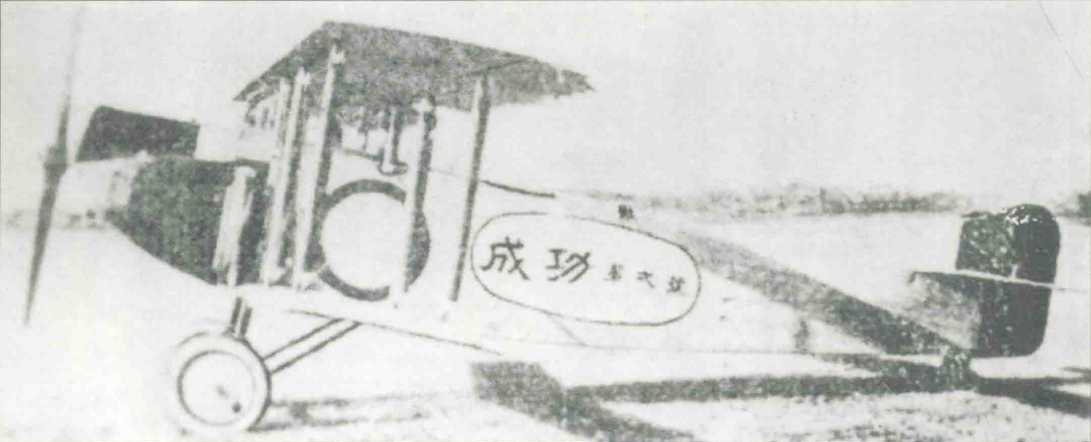

Yang Ch‘eng 51 成功號(1 built)

Yang Ch'eng 52(no picture, one built)

Yang Ch'eng 53(1 built)

Yang Ch'eng 54 & 55(54 one built, 55 one built)

Yang Ch'eng 56(1 built)

Yang Ch'eng 57 南雄號(1 built)

Yang Ch'eng 58(1 built)

Yang Ch'eng 59(1 built)

Yang Ch'eng 70 & 71 & 72 & 73(copy with Avro 616 and modified, 4 built)

Yang Ch'eng 74 & 75 & 76 & 77(Douglas O-2MC-3 copy, the fuselage is shorter than O-2MC , more than 10 built)

Yang Ch'eng 78(1 built)

Yang Ch'eng “Corsair”(copy with Vought O2U-1D Corsair, 6 built)

Yang Ch'eng(羊城號) series---60 built

Yang Ch‘eng 51 成功號(1 built)

Yang Ch'eng 52(no picture, one built)

Yang Ch'eng 53(1 built)

Yang Ch'eng 54 & 55(54 one built, 55 one built)

Yang Ch'eng 56(1 built)

Yang Ch'eng 57 南雄號(1 built)

Yang Ch'eng 58(1 built)

Yang Ch'eng 59(1 built)

Yang Ch'eng 70 & 71 & 72 & 73(copy with Avro 616 and modified, 4 built)

Yang Ch'eng 74 & 75 & 76 & 77(Douglas O-2MC-3 copy, the fuselage is shorter than O-2MC , more than 10 built)

Yang Ch'eng 78(1 built)

Yang Ch'eng “Corsair”(copy with Vought O2U-1D Corsair, 6 built)

Last edited:

bunnystar211

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 22 April 2019

- Messages

- 33

- Reaction score

- 42

Guangzhou/Kunming 1st Aircraft Manufacturer

AP-1 Fu-shing---5 built(Trainer designed and made in China, built before Aug 1937)

(AP-1 Fu-shing Prototype in Cantonese 1st Aircraft Manufacuturer )

(AP-1 Fu-shing 缅甸號 ,built in 2/18/1937)

AP-1 Type-Jia Fu-shing---22 built(Reconnaissance/Attacker designed and made in China)

AP-2 Type-Bing Fu-shing---4 built(made by birch laminate)

AP-1 Fu-Shing---1 modified(change engine, 220 hp R-675)

Chung 28B Fighter---30 built(look like I-152)

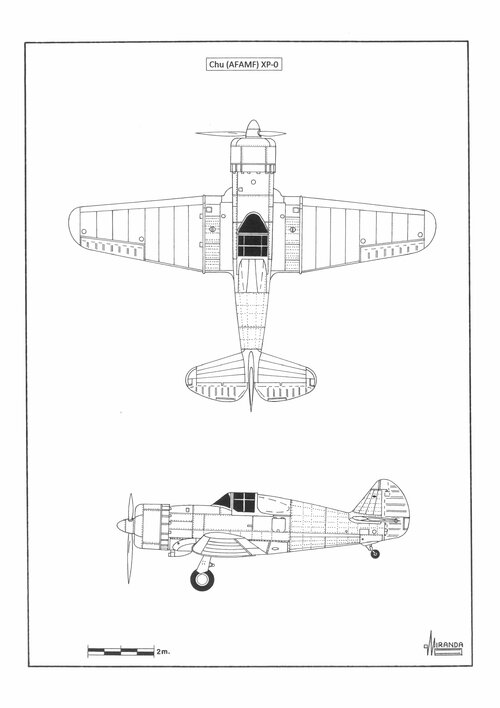

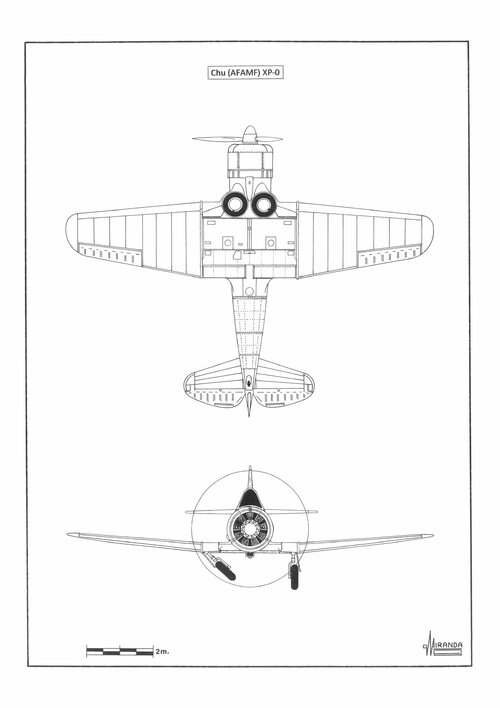

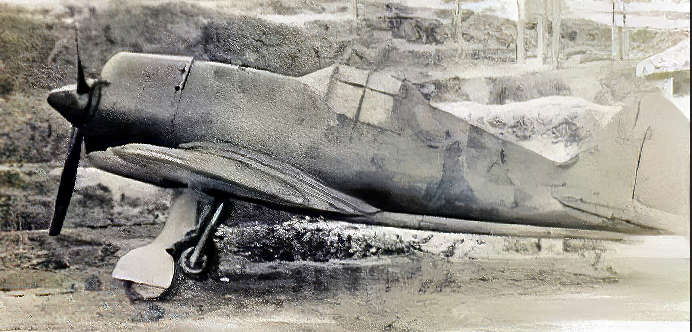

XP-0---9 built(Fighter designed and made in China)

(classical XP-0 picture, copy with Curtiss Hawk 75, 1941-1942)

(XP-0 upgrade in 1944, different appearance)

(XP-0 first fly in Lei Yun, Kunming 1942)

(XP-0 has been destroyed in factory by Japanese bomber, Lei Yun 1942)

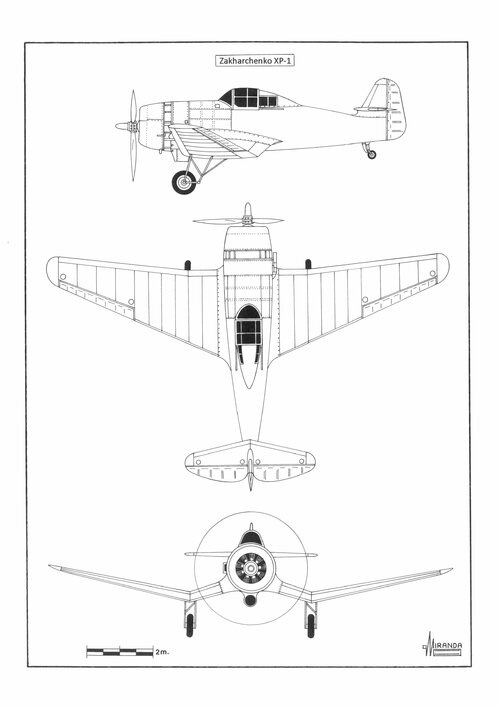

XP-1---2 built(Aircraft designed and made in China)

Hawk III---44 built(known:Curtiss Model 68C Hawk III)

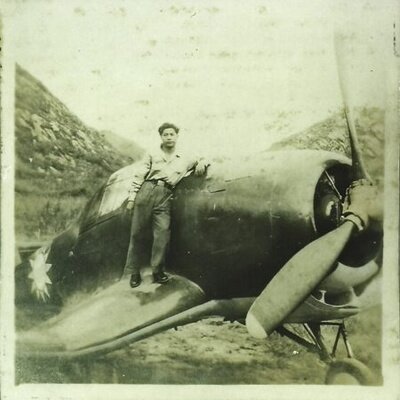

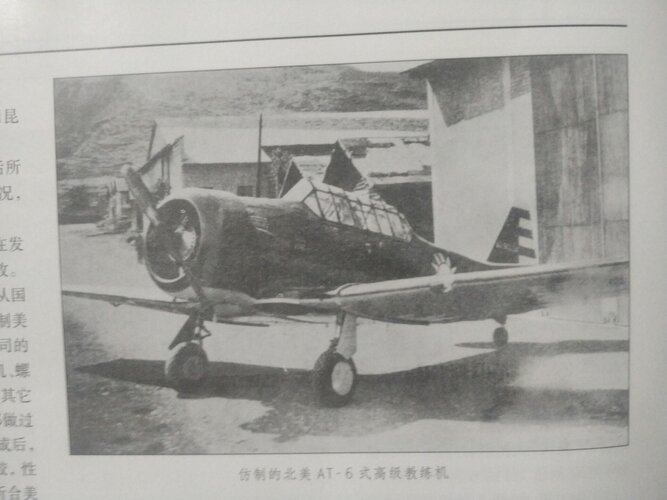

AT-6 Texan---6 built(AT-6 copy)

(different with USA/Canada T-6, see the engine cowl)

Hummingbird A helicopter---1 built(Helicopter designed and made in China)

Hummingbird B helicopter--- 2 built(Helicopter designed and made in China)

AP-1 Fu-shing---5 built(Trainer designed and made in China, built before Aug 1937)

(AP-1 Fu-shing Prototype in Cantonese 1st Aircraft Manufacuturer )

(AP-1 Fu-shing 缅甸號 ,built in 2/18/1937)

AP-1 Type-Jia Fu-shing---22 built(Reconnaissance/Attacker designed and made in China)

AP-2 Type-Bing Fu-shing---4 built(made by birch laminate)

AP-1 Fu-Shing---1 modified(change engine, 220 hp R-675)

Chung 28B Fighter---30 built(look like I-152)

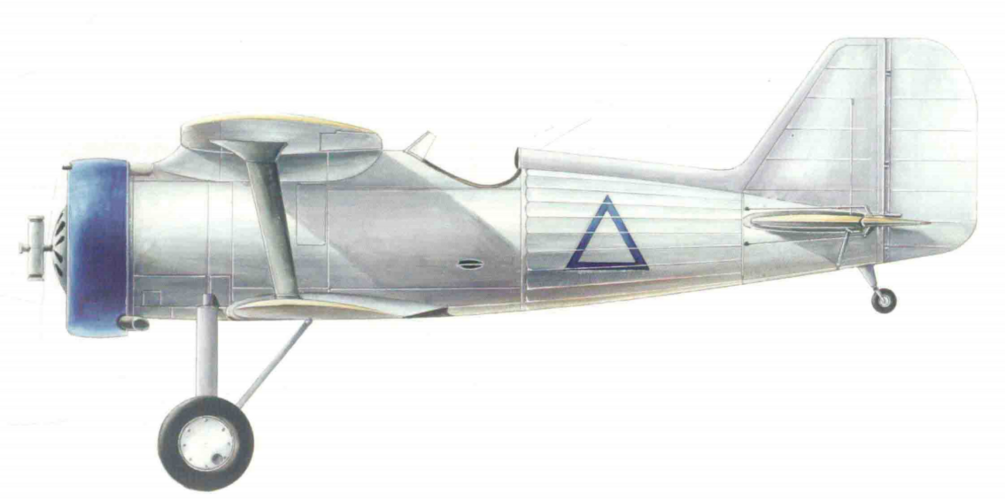

XP-0---9 built(Fighter designed and made in China)

(classical XP-0 picture, copy with Curtiss Hawk 75, 1941-1942)

(XP-0 upgrade in 1944, different appearance)

(XP-0 first fly in Lei Yun, Kunming 1942)

(XP-0 has been destroyed in factory by Japanese bomber, Lei Yun 1942)

XP-1---2 built(Aircraft designed and made in China)

Hawk III---44 built(known:Curtiss Model 68C Hawk III)

AT-6 Texan---6 built(AT-6 copy)

(different with USA/Canada T-6, see the engine cowl)

Hummingbird A helicopter---1 built(Helicopter designed and made in China)

Hummingbird B helicopter--- 2 built(Helicopter designed and made in China)

Attachments

Last edited:

bunnystar211

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 22 April 2019

- Messages

- 33

- Reaction score

- 42

happy to recived your messages. Book: 美国《飞行在中国》中国译本、《中国航空史料》作者:姜长英、《起飞在杭州》作者:杭州出版社names of the book

From the book "Enemy at the gates, panic fighters of the WWII"

On September 1931, taking advantage of a period of political weakness in China, Japan declared the independence on Manchuria and proclaimed it the new protectorate of Manchukuo.

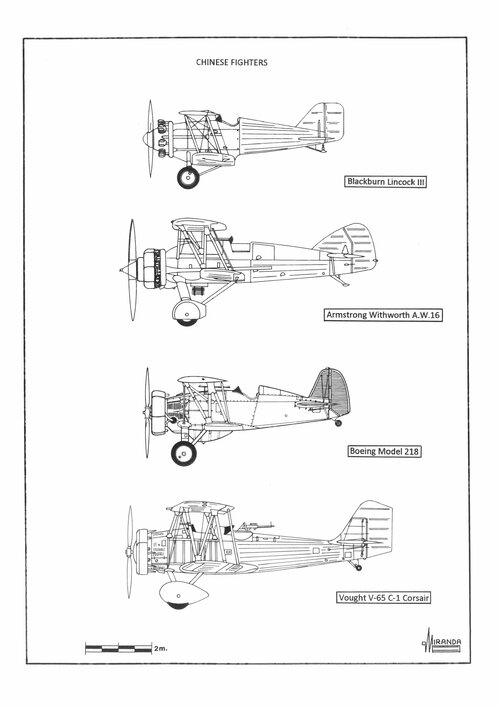

At the beginning of 1932, Mitsubishi B1M-3 bombers from IJN carrier Kaga, escorted by Nakajima A1N-2 (239 kph) fighters from IJN carrier Hosho, launched a series of attacks against Shanghai. China's air defense consisted of two Blackburn Lincock III (264 kph) fighters, the prototype Boeing 218 (304 kph) and five Vought V-65C (269 kph) fighter-bombers.

The Chinese fighters were superior to the Nakajima in speed and rate of climb, but were surprised by the exceptional manoeuvrability of the Japanese planes. During the combats over Shanghai on the 5, 22 and 26 February, the Japanese downed the Boeing, one Blackburn and two Vought.

As opposed to the heterogeneous collection of aircraft that the Chinese strove to acquire overseas, the Japanese had the advantage of the standardization of models and excellent maintenance onboard the Kaga and Hosho, as well as the local numerical superiority they could achieve by displacing the aircraft carriers.

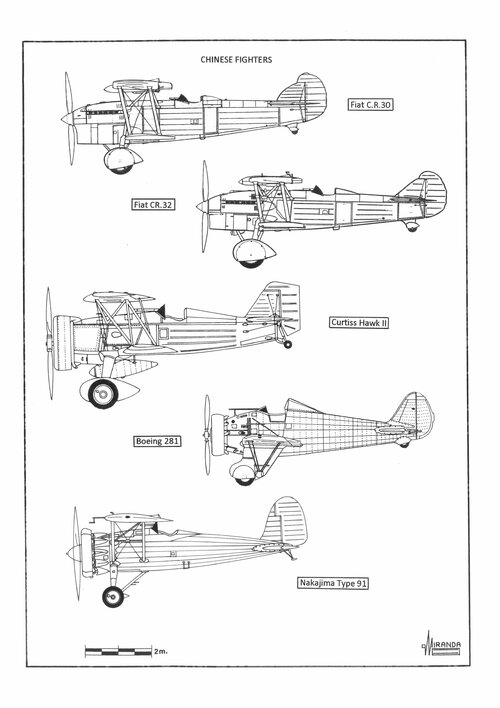

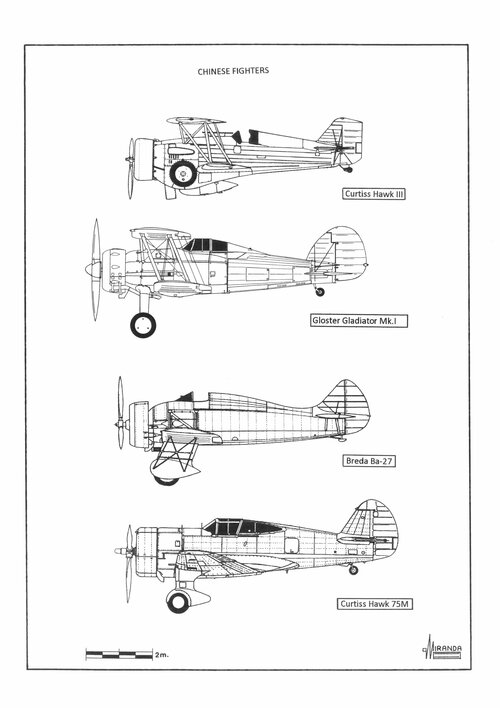

When the Japanese occupied the Jehol province in 1933, the Chinese Central Government started contacts with American and Italian aircraft manufacturers to import the modern fighters Curtiss Hawk II (335 kph), Curtiss Hawk III (386 kph), Fiat C.R.30 (370 kph), Fiat C.R.32 (375 kph) and Breda 27 (380 kph).

In 1934 they also acquired 10 monoplane fighters Boeing 281 (376 kph) and components to assemble ninety Hawk III in the new CAMCO-Shaoguan plant.

On 7 July 7 1937, an international incident was used by the Japanese to declare war on China and begin the occupation of a large part of its territory.

At that time, the Chinese Air Force (C.A.F.) strength consisted of twenty-nine Curtiss Hawk II, seventy-six Curtiss Hawk III, ten Boeing 281, ten Breda 27, three Fiat C.R. 32 fighters and hundred-and-seventy bombers of the types Northrop 2E, Douglas O2MC, Curtiss A-12, Fiat B.R.3, Heinkel He 111A, Martin 139, Savoia S.M. 72 and Vought V-92C.

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) started its attacks with 76 fighters of the types Nakajima A1N-2 Type 3 (239 kph), A2N-3 Type 90 (300 kph) AN4-1 Type 95 (352 kph), 148 bombers Aichi D1A-2, Mitsubishi B1M-3, B2M-2, G2M-1 and G3M-1 and twenty-seven Nakajima E8N-1 Type 95 floatplanes. The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) initially used 72 fighters Ki.10 Kawasaki type 95 (400 kph), 105 bombers Nakajima Ki.1, Ki.2 and Ki.3 and 12 reconnaissance airplanes Nakajima Ki.4 Type 94.

Again the use of easily replaceable self-manufactured aircraft and expert pilots favoured the Japanese. On the contrary, the level of training of the Chinese pilots was low and the maintenance of their aircraft so poor, that only a third of them were in flying condition. During the month of August, the Hawk II of the 28th Pursuit Squadron obtained some successes against the bombers G3M operating without an escort of fighters, but suffered large losses against the Ki.10 of the 16th Hiko Rentai. Henceforth the Hawk II were used in training and night fighter duties only.

The Hawk III were biplane fighters with retractable undercarriage and a very robust airframe, originally designed to operate from the U.S. Navy aircraft carriers. Superior in manoeuvrability to the A4N-1 and Ki.10, they were too slow to intercept the G3M2 Type 21 which arrived to China in September. The Hawk fought hard for two months, but lost the initiative with the appearance of the new monoplanes fighters Mitsubishi A5M1 Type 96 (370 kph) from IJN Kaga, based in Kunda airfield, which surpassed them in manoeuvrability, shooting down three Hawk without suffering any losses. The C.A.F. tried to counter the new threat by using mixed formations of Hawk III and Boeing 281, a monoplane fast enough to intercept the G3M2 but inappropriate for the dog fight because of its high wing load.

It was expected that the Hawk, fitted with oxygen equipment, would flew at 6,000 m in order to surprise the Type 96 with ‘hit and run’ attacks, but they rarely managed to achieve at height for lack of time. The available reserves of oxygen was not enough to make high-altitude patrols in a systematic way. The Chinese technical units used oxygen from the repair depots, without checking its quality and at altitude the tubes and masks sometimes frozen causing accidents.

The Chinese Air Raid Warning Net (VNOS) was not a sufficiently effective organization, its alarm signal often sounded only 5-10 minutes before the Japanese fast bombers flew over the target. As a result the Hawk III were often surprised by the Type 96 climbing at medium level, suffering heavy combat losses. Neither the Boeing achieved much success because of its scarce armament. A single fighter equipped with two 0.30 in machine guns, attacking three G3M2 in an auto defensive formation, should face nine rear gunners firing from several angles.

The same thing occurred with the Fiat C.R. 32 fighters, which armament proved insufficient when confronting the Kirasazu Kokutai G3M1 bombers during the Battle of Nanking. Its manoeuvrability turned out to be inferior to the new Mitsubishi A5M2 (370 kph). The Italian engines ran with a mixture of gasoline/alcohol/bencene and its maintenance was very problematic at that time. On October 1937 just one Fiat was in flying condition.

In China, poor maintenance of aircraft and airfields, insufficiently trained pilots and lack of spares, managed to disable three times the number of aircraft than all the Japanese attacks. By the beginning of November there was not more than forty serviceable aircraft and the best Chinese pilots had died, the C.A.F. retired to the western region of Hankow, far from the reach of the Aichi dive bombers.

Until 1945 the Japanese aircraft practically every year annihilated the C.A.F. systematically destroying aircraft, airfields and aircraft assembling factories and firing on its pilots as they descended in parachutes.

Each year the C.A.F. should be reconstructed with aircraft acquired abroad and new promotions of inexperienced pilots with little chance of survival.

Each year was more difficult to compensate losses and each year the Japanese aircraft were more numerous and more technologically advanced.

In 1937 China needed a 'Panic Fighter' able to rein the Japanese aggressor and believed found in the Polikarpov I-16, a small monoplane that had achieved good results in Spain last year, fighting against the Heinkel He 51 of the Condor Legion.

The Chinese Central Government decided to request military assistance to the USSR acquiring Soviet aircraft worth 100 million of gold dollars.

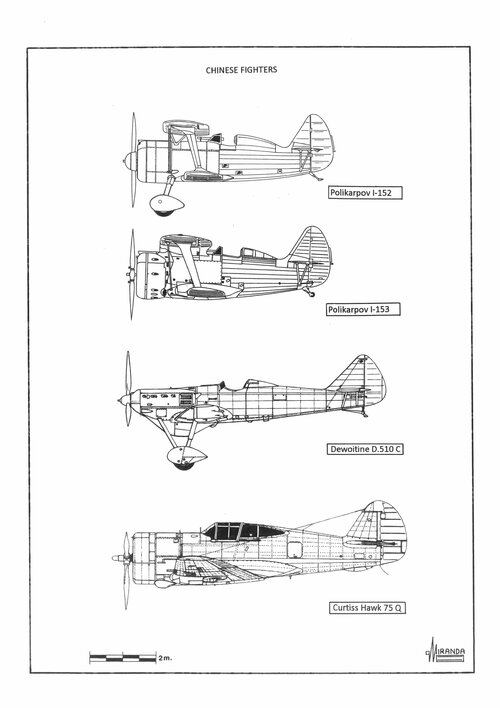

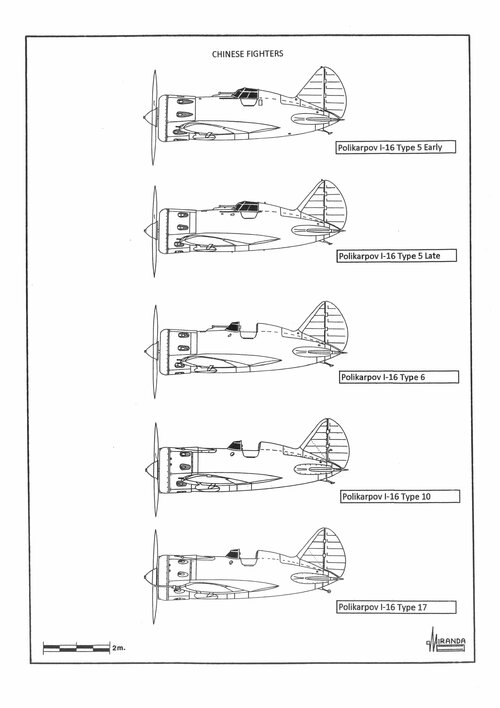

Between September 1937 and April 1941, the C.A.F. received 656 Polikarpov fighters, of which 272 were classic biplanes of the type I-152 (379 kph), 93 were biplanes with retractable landing gear of the type I-153 (444 kph) and various other versions of the I-16: twenty Type 5 (457 kph), thirty Type 6 (440 kph), ninety-two Type 10 (448 kph), seventy-five Type 17 (425 kph) and seventy-four UTI-4 two-seat trainers. They also acquired 292 modern Tupolev SB-2 bombers and a large amount of auxiliary equipment for the maintenance of the aircraft.

The contract with the Soviets also included support technique, searchlights, acoustic detectors, squads of 'voluntary' Russian pilots with combat experience in Spain and training of Chinese pilots and mechanics in the USSR, but the Japanese remained invincible in China until the end of the World War Two.

The Soviets tried to use their numerical superiority in combat tactics based on the use of large mixed formations of biplanes and monoplanes, which supported each other flying at different heights. But, as occurred during the Battle of Britain, the use of large formations only managed to aggravate the problem of rapid interception.

The Polikarpov fighters lacked the automatic starting system of the Boeing and Hawks. Their engines were to be put into operation using a Hucks starter truck that made the axis propeller turn through a system of pulleys. The procedure was slow and it was customary for the biplanes to take off first to protect the I-16s which small wings without flaps were inefficient to operate from the poorly equipped Chinese airfields.

This delayed even more the formation of a fighting force, because according to Soviet air doctrine, the monoplanes were to occupy the higher level. The slowness and clumsiness of the system benefited the Japanese, and their fast bombers often managed to surprise the Chinese fighters in the ground, causing heavy losses.

The I-152 (379 kph) was superior in armament and manoeuvrability to the Japanese fighters. It could turn 360 degrees in 11 seconds, against the 15 seconds of the A5M2 and 17 seconds of the Ki.10, but it had already given bad results in Spain because of the poor design of the central section of the upper wing, which made it lose excessive height during the horizontal turns. Besides, its armament and armour made it too heavy, making it inferior to the Japanese fighters in climb rate and maximum speed.

At the beginning of 1938 it became evident that the I-152/I-16 combination did not work against the A5M2. On February, during the defense of Hankow, the pilots of the 4th FG were forced to use the ramming against the fighters of the 13rd Kokutai. On April, the I-152 clashed for the first time with the new monoplanes Nakajima Ki.27 (460 kph) of the IJA 2nd Daitai, suffering serious losses on Kuei Teh.

By mid-thirties, the design teams of the firms Fokker Nakajima and Mitsubishi independently arrived at the same aerodynamic solution: a detailed study showed that, with the engines of less than 1,000 hp that were available at the time, it would not be effective to provide a fighter monoplane with a retractable undercarriage.

The designers estimated that disadvantages in increased weight and mechanical problems would not justify the three per cent increase in overall speed and decided to build the D.XXI, Ki.27 and A5M2 fighters with fixed undercarriage streamlined to the greatest extent possible.

During the flight tests with the prototype of the Fokker D.XXI, it was found that the drag generated by the undercarriage was only 10 per cent of the generated by the entire airframe. Subsequent experiments carried out in Finland with a D.XXI equipped with retractable landing gear, confirmed the calculations of the contractor. On the contrary, the Type 5 fastest version of the Polikarpov I-16 did not exceed the overall speed of the Ki.27 and was only 20 kph faster than the A5M2. The cause was the poor aerodynamic design of the engine cowling, equipped with a shuttered front plate.

The Type 5 also proved to be inferior in manoeuvrability regarding the Japanese monoplanes. The too short fuselage created longitudinal instability, affecting the accuracy of the weapons, and its small wings did not generate sufficient lift, penalizing their rate of climb, which was just of 73 per cent compared to the climbing rate of the Japanese fighters. The absence of flaps made manoeuvrability difficult at low speeds and caused so many landing accidents in the poorly equipped Chinese airfields that it was necessary to import several two-seat trainers of the UTI-4 type to re-training the pilots.

The firepower was increased in Type 6 with two additional 1,800 rpm rapid-fire ShKAS machine guns, to improve its effectiveness against the G3M bombers. But excess weight caused by the extra weaponry, the ammunition and the dorsal plate armour, was not fully compensated by the installation of a more powerful engine and Type 6 turned out to be even slower than its predecessor. During his first combat on Nanking, on 21 November, the Type 6 proved inferior to the A5M2.

In the spring of 1938 the Soviets introduced the Type 10 in China, armed with four ShKAS, effective against the G3M but too heavy for a dogfight against the agile Japanese fighters. The designers tried to solve the problem of excessive landing speed installing flaps powered by compressed air, but its use required some practice and even veteran pilots continued to suffer accidents. Numerical superiority was not enough to defeat the Japanese planes, which continued occupying territories. The Polikarpov fighters were abundant and cheap but they lost all the wars in which intervened.

At the beginning of 1938, faced with the failure of the Soviet material, the Chinese decided to try their luck with British technology acquiring thirty-six Gloster Gladiator Mk.I, considered the biplane fighters more effective of his time. On March the A5M2 began to use oxygen equipment that allowed them to fly at more than 6,000 m. The only Chinese fighters who could fight at that point were the Gladiator of the 5th PG that finally obtained some successes against the Mitsubishi fighters, to which they exceeded in manoeuvrability and armament.

Unfortunately for the C.A.F. the British could only give away 36 planes that were soon affected by the usual problems in the maintenance of oxygen equipment. The Gladiators also suffered frequent stoppages in the four Browning M1919 machine guns, due to the poor quality of the Belgian ammunition they used. Weapons failing, some Chinese pilots carried out ramming against the A5M2. At the end of 1939 only three Gladiators were serviceable.

During the summer of 1938 the scale of resistance of C.A.F. dramatically decreased, a third part of its 200 pilots had died and the survivors avoided the confrontation with the Japanese fighters, limited themselves to carrying out missions of strafing or night fighter with their I-152. At the end of August, the C.A.F. began its annual retreat to Western bases, leaving the burden of combat to Soviet 'volunteers'.

To keep in touch, the Ki.27 and A5M2 were equipped with belly fuel tanks that increased its operational range. They used to escort the bombers at a distance, to surprise the Chinese fighters who dared to take off believing that the bombers attacked without protection. On November, the Soviets received an order to temporarily discontinue their participation in battle.

At the end of 1938 the C.A.F. had lost 202 aircraft and had only 170 in flying condition, but the country was too large to be completely defeated. In any case the IJA started a long-range annihilation campaign against Chinese aircraft based on Lanchow and Chungking using its new Mitsubishi Ki.21 Type 97 and Fiat B.R.20 bombers. For their distant targets, bombers were to carry out missions of 1,600 km, without an escort of fighters, being occasionally intercepted by the I-16 Type 10 that the Chinese still kept. On February 1939, the losses of the IJA reached 10 per cent and the offensive was limited only to night attacks.

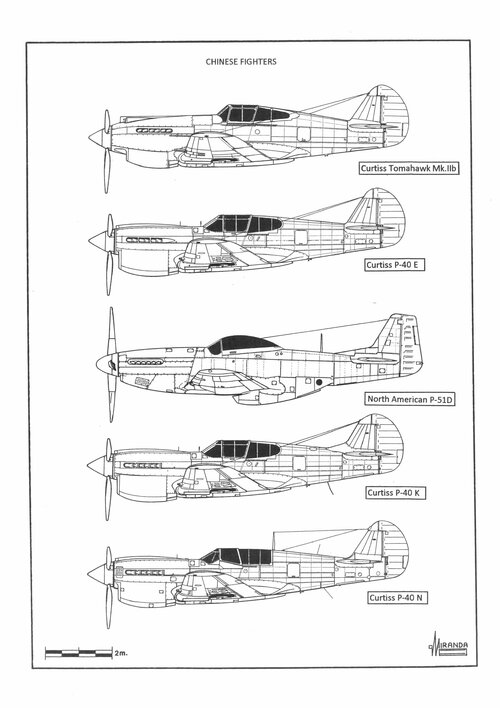

On May the IJA received orders to relocate their planes to Manchuria to fight against the Soviets in Nomonhan and the IJN preferred to concentrate their attacks only on Chungking, the new Chinese capital. The city was defended by the new American fighters Curtiss H-75M (450 kph). They were monoplanes with fixed undercarriage, as fast as the Ki.27 but less manoeuvrable and with lower rate of climb due to the large weight of auxiliary equipment: armour plates, R/T device, oxygen equipment and 12.7 mm machine guns.

Its structural resistance prevented the H-75 of suffering too many losses. But they suffered numerous accidents due to a defect in the design of the undercarriage which used to lock the wheels. The Curtiss stayed in the front line until the arrival of the Mitsubishi A6M2 Type 11 Zero-Sen (533 kph) in September 1940.

The G3M bombers also evolved becoming faster and harder to shoot down. At the end of 1939 the C.A.F. began to fight them with some French fighters Dewoitine D.510C (367 kph) armed with a 20 mm H.S. 404 cannon that allowed them to shoot the G3M without exposing themselves to the defensive fire of the rear gunners.

The Dewoitine was only 55 kph faster than the G3M and had to attack it from a higher altitude using the half-roll diving technique. But it was discovered during the first combats that this manoeuver impeded the proper functioning of the cannon that had a tendence to jam when firing in a dive This design flaw forced the French fighter to attack flying at the same level as the G3M, losing the speed advantage and increasing its exposure to defensive fire.

The situation worsened with the entry into service of the new G3M2 Model 21, as fast as the Dewoitine and armed with a 20 mm cannon Type 99 on a dorsal turret.

The D.510 were used in the defence of Chengdu until 4 December 1940, when they were decimated by the Zeros in one single combat. The two surviving aircraft continued to operate as night fighters with the 17th PS.

After the IJA failure in its ambitious offensive of strategic bombing, the IJN decided to accelerate the entry into service of the Mitsubishi A6M2 Type 11 Zero-Sen, a predator able to fly to any place of China, overcoming any opposition, thanks to its manoeuvrability and powerful armament.

On July 1940, 15 pre-production Zeros were sent to China to perform operational tests with the 12th Kokutai. They entered combat for the first time over Chungking on 13 September, against twenty-seven Polikarpov I-152 and I-16, shooting down all them without losses of their own.

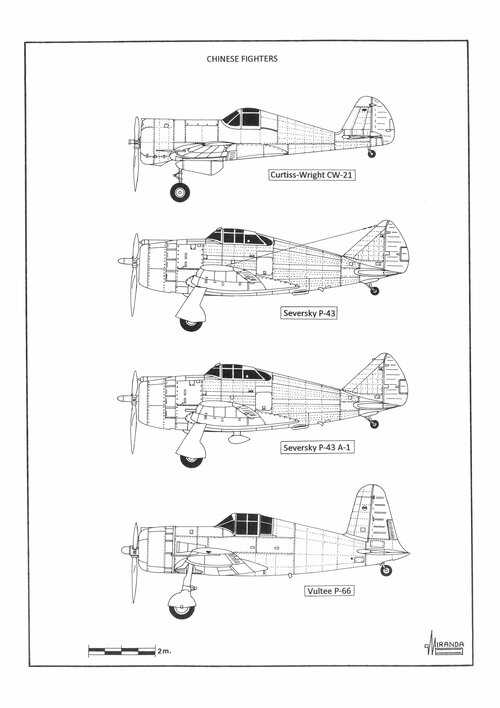

The C.A.F. tried to counter the threat using mixed formations of Curtiss H-75 Q (490 kph) and Curtiss-Wright CW-21 (476 kph).

The first model was an improved version of the H-75M equipped with retractable landing gear. It was not as fast as the Zero but armed with two 23 mm Madsen cannons, which were more powerful than the 20 mm Oerlikon Type 99-1 of the Japanese fighter. The Madsen would be lethal for the G3M2 and could also be used in ground attack duties. The CW-21 ‘Interceptor’ was a high-altitude light fighter with a phenomenal climb rate of 24.4 m/sec.

On March 1939 the demonstration prototype was flown in mock combats against Chinese I-152, I-16 and D.510 fighters proving its superiority in climb rate and speed. Surprisingly, the CW-21 also proved to be superior in manoeuvrability through usage of step climbs and wing overs by an experienced driver.

The Central Government acquired the prototype, three pre-production aircraft and thirty sets of components for local assemblage at CAMCO-Loiwing facilities. It was to carry an armament of two 7.62 mm Madsen machine guns, with 1,000 rounds per gun and two 11.35 mm Madsen heavy machine guns with 400 rounds per gun, mounted in the cowl.

In the production version, the original Pyrolin plastic windscreen was to be replaced by a three-piece armour-glass assembly. Provision for belly tanks to be added. The modifications would increase the take-off weight to 1,975 kg with 4 per cent reduction of the maximum speed.

On 26 October 1940 the CAMCO factory was bombarded by fifty-nine G3M2 Model 21 from 15th Kokutai, escorted by forty Zeros, many of the partially assembled CW-21 were destroyed. In the autumn of 1941 the three pre-production machines were transferred to the A.V.G's 3rd Squadron operating from the Rangoon-Mingaladon airfield.

The slow climbing P-40B could not catch the high flying reconnaissance airplanes Mitsubishi Ki.46-II Dinah of the IJA 8th Sentai and three CW-21 were sent to the A.V.G. base at Kyedaw with the mission to intercept them. Unfortunately, all the ‘Interceptors’ were destroyed during the ferry flight, consequence of the poor quality of the 70-74 octane fuel supplied by the C.A.F.

There are no reliable data on the career of the CW-21 in China. A to some authors the prototype shot down a Fiat B.R.20 over Chungking on 2 April 1939, but this was not confirmed by Japanese sources. In 1942 the Chinese rebuilt at least two aircraft with parts recovered in CAMCO, but it is ignored if they were even involved in fight.

The ‘Interceptor’ surpassed in climb and roll the Ki.27-II, Mitsubishi A5M4 Type 96 and A6M2 Model 11. It was the only Allies fighter in the Far East able to match the performance of the Japanese fighters, but did not have the opportunity to prove it, neither in China nor in the Dutch East Indies, for reasons beyond their original design.

China (28 January 1932 to August 15 1945)

On September 1931, taking advantage of a period of political weakness in China, Japan declared the independence on Manchuria and proclaimed it the new protectorate of Manchukuo.

At the beginning of 1932, Mitsubishi B1M-3 bombers from IJN carrier Kaga, escorted by Nakajima A1N-2 (239 kph) fighters from IJN carrier Hosho, launched a series of attacks against Shanghai. China's air defense consisted of two Blackburn Lincock III (264 kph) fighters, the prototype Boeing 218 (304 kph) and five Vought V-65C (269 kph) fighter-bombers.

The Chinese fighters were superior to the Nakajima in speed and rate of climb, but were surprised by the exceptional manoeuvrability of the Japanese planes. During the combats over Shanghai on the 5, 22 and 26 February, the Japanese downed the Boeing, one Blackburn and two Vought.

As opposed to the heterogeneous collection of aircraft that the Chinese strove to acquire overseas, the Japanese had the advantage of the standardization of models and excellent maintenance onboard the Kaga and Hosho, as well as the local numerical superiority they could achieve by displacing the aircraft carriers.

When the Japanese occupied the Jehol province in 1933, the Chinese Central Government started contacts with American and Italian aircraft manufacturers to import the modern fighters Curtiss Hawk II (335 kph), Curtiss Hawk III (386 kph), Fiat C.R.30 (370 kph), Fiat C.R.32 (375 kph) and Breda 27 (380 kph).

In 1934 they also acquired 10 monoplane fighters Boeing 281 (376 kph) and components to assemble ninety Hawk III in the new CAMCO-Shaoguan plant.

On 7 July 7 1937, an international incident was used by the Japanese to declare war on China and begin the occupation of a large part of its territory.

At that time, the Chinese Air Force (C.A.F.) strength consisted of twenty-nine Curtiss Hawk II, seventy-six Curtiss Hawk III, ten Boeing 281, ten Breda 27, three Fiat C.R. 32 fighters and hundred-and-seventy bombers of the types Northrop 2E, Douglas O2MC, Curtiss A-12, Fiat B.R.3, Heinkel He 111A, Martin 139, Savoia S.M. 72 and Vought V-92C.

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) started its attacks with 76 fighters of the types Nakajima A1N-2 Type 3 (239 kph), A2N-3 Type 90 (300 kph) AN4-1 Type 95 (352 kph), 148 bombers Aichi D1A-2, Mitsubishi B1M-3, B2M-2, G2M-1 and G3M-1 and twenty-seven Nakajima E8N-1 Type 95 floatplanes. The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) initially used 72 fighters Ki.10 Kawasaki type 95 (400 kph), 105 bombers Nakajima Ki.1, Ki.2 and Ki.3 and 12 reconnaissance airplanes Nakajima Ki.4 Type 94.

Again the use of easily replaceable self-manufactured aircraft and expert pilots favoured the Japanese. On the contrary, the level of training of the Chinese pilots was low and the maintenance of their aircraft so poor, that only a third of them were in flying condition. During the month of August, the Hawk II of the 28th Pursuit Squadron obtained some successes against the bombers G3M operating without an escort of fighters, but suffered large losses against the Ki.10 of the 16th Hiko Rentai. Henceforth the Hawk II were used in training and night fighter duties only.

The Hawk III were biplane fighters with retractable undercarriage and a very robust airframe, originally designed to operate from the U.S. Navy aircraft carriers. Superior in manoeuvrability to the A4N-1 and Ki.10, they were too slow to intercept the G3M2 Type 21 which arrived to China in September. The Hawk fought hard for two months, but lost the initiative with the appearance of the new monoplanes fighters Mitsubishi A5M1 Type 96 (370 kph) from IJN Kaga, based in Kunda airfield, which surpassed them in manoeuvrability, shooting down three Hawk without suffering any losses. The C.A.F. tried to counter the new threat by using mixed formations of Hawk III and Boeing 281, a monoplane fast enough to intercept the G3M2 but inappropriate for the dog fight because of its high wing load.

It was expected that the Hawk, fitted with oxygen equipment, would flew at 6,000 m in order to surprise the Type 96 with ‘hit and run’ attacks, but they rarely managed to achieve at height for lack of time. The available reserves of oxygen was not enough to make high-altitude patrols in a systematic way. The Chinese technical units used oxygen from the repair depots, without checking its quality and at altitude the tubes and masks sometimes frozen causing accidents.

The Chinese Air Raid Warning Net (VNOS) was not a sufficiently effective organization, its alarm signal often sounded only 5-10 minutes before the Japanese fast bombers flew over the target. As a result the Hawk III were often surprised by the Type 96 climbing at medium level, suffering heavy combat losses. Neither the Boeing achieved much success because of its scarce armament. A single fighter equipped with two 0.30 in machine guns, attacking three G3M2 in an auto defensive formation, should face nine rear gunners firing from several angles.

The same thing occurred with the Fiat C.R. 32 fighters, which armament proved insufficient when confronting the Kirasazu Kokutai G3M1 bombers during the Battle of Nanking. Its manoeuvrability turned out to be inferior to the new Mitsubishi A5M2 (370 kph). The Italian engines ran with a mixture of gasoline/alcohol/bencene and its maintenance was very problematic at that time. On October 1937 just one Fiat was in flying condition.

In China, poor maintenance of aircraft and airfields, insufficiently trained pilots and lack of spares, managed to disable three times the number of aircraft than all the Japanese attacks. By the beginning of November there was not more than forty serviceable aircraft and the best Chinese pilots had died, the C.A.F. retired to the western region of Hankow, far from the reach of the Aichi dive bombers.

Until 1945 the Japanese aircraft practically every year annihilated the C.A.F. systematically destroying aircraft, airfields and aircraft assembling factories and firing on its pilots as they descended in parachutes.

Each year the C.A.F. should be reconstructed with aircraft acquired abroad and new promotions of inexperienced pilots with little chance of survival.

Each year was more difficult to compensate losses and each year the Japanese aircraft were more numerous and more technologically advanced.

In 1937 China needed a 'Panic Fighter' able to rein the Japanese aggressor and believed found in the Polikarpov I-16, a small monoplane that had achieved good results in Spain last year, fighting against the Heinkel He 51 of the Condor Legion.

The Chinese Central Government decided to request military assistance to the USSR acquiring Soviet aircraft worth 100 million of gold dollars.

Between September 1937 and April 1941, the C.A.F. received 656 Polikarpov fighters, of which 272 were classic biplanes of the type I-152 (379 kph), 93 were biplanes with retractable landing gear of the type I-153 (444 kph) and various other versions of the I-16: twenty Type 5 (457 kph), thirty Type 6 (440 kph), ninety-two Type 10 (448 kph), seventy-five Type 17 (425 kph) and seventy-four UTI-4 two-seat trainers. They also acquired 292 modern Tupolev SB-2 bombers and a large amount of auxiliary equipment for the maintenance of the aircraft.

The contract with the Soviets also included support technique, searchlights, acoustic detectors, squads of 'voluntary' Russian pilots with combat experience in Spain and training of Chinese pilots and mechanics in the USSR, but the Japanese remained invincible in China until the end of the World War Two.

The Soviets tried to use their numerical superiority in combat tactics based on the use of large mixed formations of biplanes and monoplanes, which supported each other flying at different heights. But, as occurred during the Battle of Britain, the use of large formations only managed to aggravate the problem of rapid interception.

The Polikarpov fighters lacked the automatic starting system of the Boeing and Hawks. Their engines were to be put into operation using a Hucks starter truck that made the axis propeller turn through a system of pulleys. The procedure was slow and it was customary for the biplanes to take off first to protect the I-16s which small wings without flaps were inefficient to operate from the poorly equipped Chinese airfields.

This delayed even more the formation of a fighting force, because according to Soviet air doctrine, the monoplanes were to occupy the higher level. The slowness and clumsiness of the system benefited the Japanese, and their fast bombers often managed to surprise the Chinese fighters in the ground, causing heavy losses.

The I-152 (379 kph) was superior in armament and manoeuvrability to the Japanese fighters. It could turn 360 degrees in 11 seconds, against the 15 seconds of the A5M2 and 17 seconds of the Ki.10, but it had already given bad results in Spain because of the poor design of the central section of the upper wing, which made it lose excessive height during the horizontal turns. Besides, its armament and armour made it too heavy, making it inferior to the Japanese fighters in climb rate and maximum speed.

At the beginning of 1938 it became evident that the I-152/I-16 combination did not work against the A5M2. On February, during the defense of Hankow, the pilots of the 4th FG were forced to use the ramming against the fighters of the 13rd Kokutai. On April, the I-152 clashed for the first time with the new monoplanes Nakajima Ki.27 (460 kph) of the IJA 2nd Daitai, suffering serious losses on Kuei Teh.

By mid-thirties, the design teams of the firms Fokker Nakajima and Mitsubishi independently arrived at the same aerodynamic solution: a detailed study showed that, with the engines of less than 1,000 hp that were available at the time, it would not be effective to provide a fighter monoplane with a retractable undercarriage.

The designers estimated that disadvantages in increased weight and mechanical problems would not justify the three per cent increase in overall speed and decided to build the D.XXI, Ki.27 and A5M2 fighters with fixed undercarriage streamlined to the greatest extent possible.

During the flight tests with the prototype of the Fokker D.XXI, it was found that the drag generated by the undercarriage was only 10 per cent of the generated by the entire airframe. Subsequent experiments carried out in Finland with a D.XXI equipped with retractable landing gear, confirmed the calculations of the contractor. On the contrary, the Type 5 fastest version of the Polikarpov I-16 did not exceed the overall speed of the Ki.27 and was only 20 kph faster than the A5M2. The cause was the poor aerodynamic design of the engine cowling, equipped with a shuttered front plate.

The Type 5 also proved to be inferior in manoeuvrability regarding the Japanese monoplanes. The too short fuselage created longitudinal instability, affecting the accuracy of the weapons, and its small wings did not generate sufficient lift, penalizing their rate of climb, which was just of 73 per cent compared to the climbing rate of the Japanese fighters. The absence of flaps made manoeuvrability difficult at low speeds and caused so many landing accidents in the poorly equipped Chinese airfields that it was necessary to import several two-seat trainers of the UTI-4 type to re-training the pilots.

The firepower was increased in Type 6 with two additional 1,800 rpm rapid-fire ShKAS machine guns, to improve its effectiveness against the G3M bombers. But excess weight caused by the extra weaponry, the ammunition and the dorsal plate armour, was not fully compensated by the installation of a more powerful engine and Type 6 turned out to be even slower than its predecessor. During his first combat on Nanking, on 21 November, the Type 6 proved inferior to the A5M2.

In the spring of 1938 the Soviets introduced the Type 10 in China, armed with four ShKAS, effective against the G3M but too heavy for a dogfight against the agile Japanese fighters. The designers tried to solve the problem of excessive landing speed installing flaps powered by compressed air, but its use required some practice and even veteran pilots continued to suffer accidents. Numerical superiority was not enough to defeat the Japanese planes, which continued occupying territories. The Polikarpov fighters were abundant and cheap but they lost all the wars in which intervened.

At the beginning of 1938, faced with the failure of the Soviet material, the Chinese decided to try their luck with British technology acquiring thirty-six Gloster Gladiator Mk.I, considered the biplane fighters more effective of his time. On March the A5M2 began to use oxygen equipment that allowed them to fly at more than 6,000 m. The only Chinese fighters who could fight at that point were the Gladiator of the 5th PG that finally obtained some successes against the Mitsubishi fighters, to which they exceeded in manoeuvrability and armament.

Unfortunately for the C.A.F. the British could only give away 36 planes that were soon affected by the usual problems in the maintenance of oxygen equipment. The Gladiators also suffered frequent stoppages in the four Browning M1919 machine guns, due to the poor quality of the Belgian ammunition they used. Weapons failing, some Chinese pilots carried out ramming against the A5M2. At the end of 1939 only three Gladiators were serviceable.

During the summer of 1938 the scale of resistance of C.A.F. dramatically decreased, a third part of its 200 pilots had died and the survivors avoided the confrontation with the Japanese fighters, limited themselves to carrying out missions of strafing or night fighter with their I-152. At the end of August, the C.A.F. began its annual retreat to Western bases, leaving the burden of combat to Soviet 'volunteers'.

To keep in touch, the Ki.27 and A5M2 were equipped with belly fuel tanks that increased its operational range. They used to escort the bombers at a distance, to surprise the Chinese fighters who dared to take off believing that the bombers attacked without protection. On November, the Soviets received an order to temporarily discontinue their participation in battle.

At the end of 1938 the C.A.F. had lost 202 aircraft and had only 170 in flying condition, but the country was too large to be completely defeated. In any case the IJA started a long-range annihilation campaign against Chinese aircraft based on Lanchow and Chungking using its new Mitsubishi Ki.21 Type 97 and Fiat B.R.20 bombers. For their distant targets, bombers were to carry out missions of 1,600 km, without an escort of fighters, being occasionally intercepted by the I-16 Type 10 that the Chinese still kept. On February 1939, the losses of the IJA reached 10 per cent and the offensive was limited only to night attacks.

On May the IJA received orders to relocate their planes to Manchuria to fight against the Soviets in Nomonhan and the IJN preferred to concentrate their attacks only on Chungking, the new Chinese capital. The city was defended by the new American fighters Curtiss H-75M (450 kph). They were monoplanes with fixed undercarriage, as fast as the Ki.27 but less manoeuvrable and with lower rate of climb due to the large weight of auxiliary equipment: armour plates, R/T device, oxygen equipment and 12.7 mm machine guns.

Its structural resistance prevented the H-75 of suffering too many losses. But they suffered numerous accidents due to a defect in the design of the undercarriage which used to lock the wheels. The Curtiss stayed in the front line until the arrival of the Mitsubishi A6M2 Type 11 Zero-Sen (533 kph) in September 1940.

The G3M bombers also evolved becoming faster and harder to shoot down. At the end of 1939 the C.A.F. began to fight them with some French fighters Dewoitine D.510C (367 kph) armed with a 20 mm H.S. 404 cannon that allowed them to shoot the G3M without exposing themselves to the defensive fire of the rear gunners.

The Dewoitine was only 55 kph faster than the G3M and had to attack it from a higher altitude using the half-roll diving technique. But it was discovered during the first combats that this manoeuver impeded the proper functioning of the cannon that had a tendence to jam when firing in a dive This design flaw forced the French fighter to attack flying at the same level as the G3M, losing the speed advantage and increasing its exposure to defensive fire.

The situation worsened with the entry into service of the new G3M2 Model 21, as fast as the Dewoitine and armed with a 20 mm cannon Type 99 on a dorsal turret.

The D.510 were used in the defence of Chengdu until 4 December 1940, when they were decimated by the Zeros in one single combat. The two surviving aircraft continued to operate as night fighters with the 17th PS.

After the IJA failure in its ambitious offensive of strategic bombing, the IJN decided to accelerate the entry into service of the Mitsubishi A6M2 Type 11 Zero-Sen, a predator able to fly to any place of China, overcoming any opposition, thanks to its manoeuvrability and powerful armament.

On July 1940, 15 pre-production Zeros were sent to China to perform operational tests with the 12th Kokutai. They entered combat for the first time over Chungking on 13 September, against twenty-seven Polikarpov I-152 and I-16, shooting down all them without losses of their own.

The C.A.F. tried to counter the threat using mixed formations of Curtiss H-75 Q (490 kph) and Curtiss-Wright CW-21 (476 kph).

The first model was an improved version of the H-75M equipped with retractable landing gear. It was not as fast as the Zero but armed with two 23 mm Madsen cannons, which were more powerful than the 20 mm Oerlikon Type 99-1 of the Japanese fighter. The Madsen would be lethal for the G3M2 and could also be used in ground attack duties. The CW-21 ‘Interceptor’ was a high-altitude light fighter with a phenomenal climb rate of 24.4 m/sec.

On March 1939 the demonstration prototype was flown in mock combats against Chinese I-152, I-16 and D.510 fighters proving its superiority in climb rate and speed. Surprisingly, the CW-21 also proved to be superior in manoeuvrability through usage of step climbs and wing overs by an experienced driver.

The Central Government acquired the prototype, three pre-production aircraft and thirty sets of components for local assemblage at CAMCO-Loiwing facilities. It was to carry an armament of two 7.62 mm Madsen machine guns, with 1,000 rounds per gun and two 11.35 mm Madsen heavy machine guns with 400 rounds per gun, mounted in the cowl.

In the production version, the original Pyrolin plastic windscreen was to be replaced by a three-piece armour-glass assembly. Provision for belly tanks to be added. The modifications would increase the take-off weight to 1,975 kg with 4 per cent reduction of the maximum speed.

On 26 October 1940 the CAMCO factory was bombarded by fifty-nine G3M2 Model 21 from 15th Kokutai, escorted by forty Zeros, many of the partially assembled CW-21 were destroyed. In the autumn of 1941 the three pre-production machines were transferred to the A.V.G's 3rd Squadron operating from the Rangoon-Mingaladon airfield.

The slow climbing P-40B could not catch the high flying reconnaissance airplanes Mitsubishi Ki.46-II Dinah of the IJA 8th Sentai and three CW-21 were sent to the A.V.G. base at Kyedaw with the mission to intercept them. Unfortunately, all the ‘Interceptors’ were destroyed during the ferry flight, consequence of the poor quality of the 70-74 octane fuel supplied by the C.A.F.

There are no reliable data on the career of the CW-21 in China. A to some authors the prototype shot down a Fiat B.R.20 over Chungking on 2 April 1939, but this was not confirmed by Japanese sources. In 1942 the Chinese rebuilt at least two aircraft with parts recovered in CAMCO, but it is ignored if they were even involved in fight.

The ‘Interceptor’ surpassed in climb and roll the Ki.27-II, Mitsubishi A5M4 Type 96 and A6M2 Model 11. It was the only Allies fighter in the Far East able to match the performance of the Japanese fighters, but did not have the opportunity to prove it, neither in China nor in the Dutch East Indies, for reasons beyond their original design.

post-2

CW-21 technical data

Wingspan: 10.66 m, length: 8.03 m, height: 2.60 m, wing area: 16.19 sq.m, max weight: 1,896 kg, maximum - speed: 476 kph, range: 853 km, power plant: one 1,000 hp Wright Cyclone R-1820-G5 air-cooled radial engine.

The contract with the firm Curtiss included the import of an H-75Q and components for the manufacture of forty-nine H-75Q in CAMCO. Unfortunately for the Chinese, the Zero could fly for 3,100 km, remaining more than 8 hours in the air. This capacity allowed them to escort the G3M2 to the most remote sanctuary-bases of the C.A.F. preventing its annual re-organization

On May 1940 the G3M2 Model 22 started to be used in China. They used oxygen equipment and 87 octane fuel to fly at 7,000 m, attacking the Chinese airfields with the new bombs Type 2, Mk 21 of 52.5 kg. Each of them consisting of a canister containing thirty-six H.E. submunitions. The G3M2 used to operate in collaboration with the Mitsubishi C5M2 Type 88 fast reconnaissance airplanes that informed them by radio when the Chinese fighters landed for refuelling.

During August the IJA continued the attacks against Kunming and Chengtu using the new Mitsubishi Ki.21 bombers. Between 19 August 1940 and 15 September 1941 the Zeros downed 103 planes of the C.A.F. and destroyed other 162 in strafing missions. The Soviets tried to fight the Zeros using mixed formations of I-153, I-16 Type 10 and Type 17 fighters flying in three levels at 7,500 m, 7,000 m and 6,500 m.

After numerous tests with an A5M2 captured in China, the Soviets came to the conclusion that the Polikarpov I-153 (444 kph) were more capable of tracking the Japanese monoplane on equal terms.

The I-153 was as fast as the I-16 Type 6, its climb rate the highest of all Soviet fighters and its gull wing configuration allowed it to turn 360 degrees in 13.3 seconds, without losing height at every turn. It was very well armed with four rapid-fire ShKas machine guns and equipped with a PAK-1 reflex gunsight, oxygen, armour plates and RSI-3 R/T device. The I-16 Type 17 was more slow, with a rate of climb of just 9.4 m/sec (the Zero had 15.75 m/sec) consequence of the additional weight of the two 20 mm ShVAK cannons and their ammunition.

The Soviets considered this armament was necessary to combat the new G4M1 weapons bombers. But it turned out that both the Zero and the G4M1 were equally armed with cannons and the Japanese fighter not only was 100 kph faster than the I-153, but it could also turn on only 11.2 seconds.

Confronted with the Zero, the Polikarpov I-153 could not flee and, if they decided to fight, they were systematically shot down. On 14 March 1941, in their first combat over Shuang-Liu airfield, the I-153 lost 13 to 0. After this last failure, the USSR decided to abandon the China adventure to concentrate on defending its European borders.

Foreign observers doubted the combat potential of the C.A.F. remaining force. On April 1941 the situation alarmed the US Administration, who authorized the creation of the A.V.G., an expeditionary force consisting of three squadrons of Curtiss P-40B (566 kph) Flying Tigers. On August the U.S. Administration imposed an oil embargo on Japan and the 87-octane gasoline would no longer available.

On September, the IJN started to concentrate its forces in Japan and Taiwan to prepare the attack against Philippines and Pearl Harbour. Until then, the Japanese losses were of 287 aircraft shot down in combat and 100 in accidents. Those of the C.A.F. were 355 aircraft downed and 1,230 in strafing and accidents. By early November the C.A.F. had been reduced to 29 fighters, 60 bombers and 42 various other aircraft.

After the destruction of the only Curtiss ‘Interceptor’ available in China, the A.V.G. had no means to intercept the high-flying Mitsubishi Ki.46-II Dinah reconnaissance airplanes from the IJA 8th Sentai. To provide high-altitude cover to the slow P-40B, the U.S. Administration authorized the export to China of seventy-two fighters Republic P-43 ‘Lancer’ and hundred-and-eight P-43 A-1‘Chinese Lancer’, through Lend-Lease Act.

The long sea voyage damaged the Fairplane cement used to seal the wing fuel tanks, a circumstance that went unnoticed during its assembly in India and that caused the loss of 139 aircraft during the Karachi-Chengtu ferry flight. Most of the accidents were fires caused by the fuel dripping under the fuselage belly until reaching the hot turbo-exhaust.

On July 1942, ten P-43A were delivered to the A.V.G. The turbo-supercharger provided the Lancer good power through 9,000 m and American pilots who tested it in flight were satisfied with its good handly and rapid rate of roll, but the A.V.G. staff did not trust them as interceptors and chose to use them as reconnaissance airplanes. However, one of them managed to shoot down a Dinah over Bhamo.

The P-43 A-1 were used by the C.A.F. against the Ki.46, with little success, since both models had the same speed at 6,000 m. On 24 October 1942, the 24th Sqn ‘Chinese Lancers’ downed a Dinah, from 18th Dokuritsu Chutai, over Si Bao and one Kawasaki Ki.48 from 16th Sentai over Han-Sou on 12 January 1943.

The turbo-supercharger was a complex piece of equipment and the C.A.F. simply did not have the resources to train people to properly maintain the units. The P-43 A-1 had a limited use in combat and the Dinah completely lost its immunity only when the Lockheed P-38 began operating in the Far East.

P-43 A-1 technical data

Wingspan: 10.97 m, length: 8.68 m, height: 4.26 m, wing area: 20.72 sq.m, max weight: 3,846 kg, max speed: 573 kph, range: 2,333 km, power plant: one 1,200 hp Pratt & Whitney R-1830-57 air-cooled radial engine, armament: two 12.7 mm heavy machine guns mounted in the cowl and two 12.7 mm in the wings.

In 1939 the firm Vultee Aircraft developed the Model 48C, a monoplane light fighter based on the airframe of the Valiant trainer.

On 6 February 1940 the Swedish government ordered 144 fighters Vultee Model 48C but, fearing that the airplanes might fall into Soviet hands, the U.S. State Department placed an embargo on the export of military aircraft to Sweden in October 18. On February 1942 the Roosevelt Administration allowed the export to China via Karachi of 119 fighters Model 48C, under the designation P-66 ‘Vanguard’.

They fought against the Ki.48 Type 99 bombers of the 90th Sentai and their escort fighters Nakajima Ki.43-I east of Enshih airfield on 6 June. In August, twenty-one Type 97 bombers from 58th Sentai performing a raid over Chungking, escorted by thirty-one Ki.43-I from 25th and 33rd Sentais, were intercepted by ten P-40B, eight P-43 A-1 and eleven P-66. Two ‘Vanguards’ were shot down by the Nakajima fighters.

On October 1942, the C.A.F. tried to use them against the Dinah, again without any success. In China, the ‘Vanguard’ did exhibit some handling problems during high speed dives, poor lateral stability and undesirable stalling characteristics during landing. Corrosion problems resulting from an inadequate maintenance of the weak landing gear, caused frequent ground loops and broken tailwheels. On December 1943 the 53 serviceable Vanguards were removed from to combat status and used only for training duties.

P-66 technical data

Wingspan: 10.97 m, lenght: 8.66 m, height: 2.87 m, wing area: 18.30 sq.m, max weight: 3,221 kg, max speed: 574 kph, range: 1,386 km, power plant: one 1,200 hp Pratt & Whitney R-1830-33 air-cooled radial engine, armament: two 12.7 mm heavy machine guns mounted in the cowl and four 7.62 mm in the wings.

At the time of their acquisition the Polikarpov I-16 Type 5, the Dewoitine D.510C, the Curtiss H-75M, the Curtiss CW-21, the Republic P-43 and the Vultee P-66 were considered 'Panic Fighters' although none of them managed to overcome its Japanese equivalents in this long war. But the real Chinese 'Panic Fighters' were some indigenous aircraft designed and built in desperate circumstances.

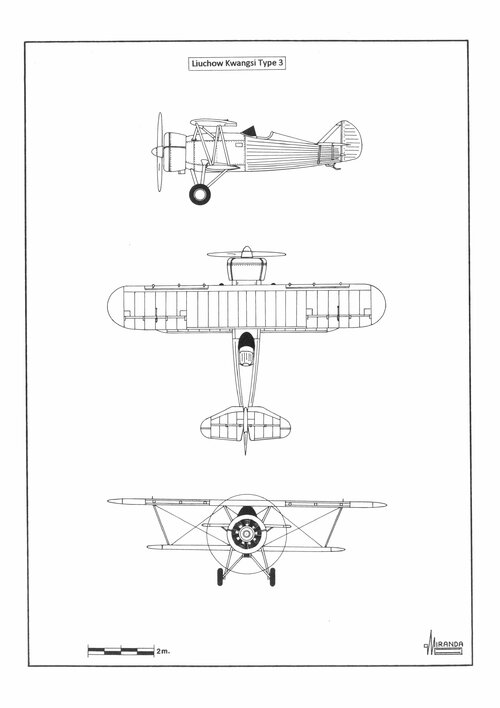

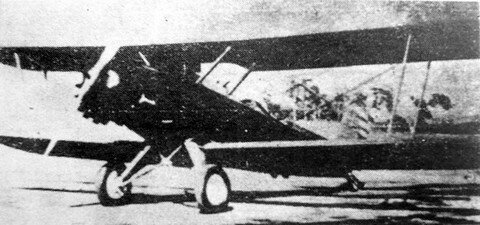

At the beginning of 1937, the designer Chee Wing Jeang built the Kwangsi Type 3, a biplane fighter developed at the Liuchow Mechanical Aircraft Factory for the Kwangsi Independent Air Force. The only prototype was built with wood/plywood wings and steel-tube/fabric fuselage. It flew for the first time on July, powered by a 260 hp Armstrong Siddeley Cheetah IIA air-cooled radial engine. Its performances proved insufficient to justify further development.

Kwangsi Type3 technical data

Wingspan: 8.0 m, length: 6.25 m, height: 2.5 m, wing area: 22 sq.m, max weight: 1,043 kg, max speed: 283 kph, rate of climb: 5.28 m/sec, armament: one 7.7mm machine gun synchronized with the propeller.

In the summer of 1937 Japanese bombers bombarded the Shaoguan Aircraft Factory, where the Hawk III fighters were assembled, and the Factory was moved to Hangzhou. But it was also bombed there before entering service. Production continued in the First Aircraft Factory of Kun-Ming in Yunnan Province in 1938. After a new attack they moved to Loiwing by mid-1939, but the new location was destroyed in the bombing of 26 October 1940 and occupied by Japanese troops on May 1942.

In 1943 the Aircraft Factory was dispersed in several locations, around Kun-Ming, where seven Hawk 75 A-5 and two CW-21 were built using parts recovered from the destroyed factories. The Aviation Research Institute was installed in one Yangling cave, where General Major Chu Chia-Jen designed the new Chinese XP-0 fighter in 1941.

A unique prototype was manufactured in 1943 by AFAMF-Yangling, using the tail surfaces of a Hawk 75, the centre section of the wing and the landing gear of a North American NA-6, the tailwheel from P-43 and the engine and cockpit of a P-66. The wings were built in wood/plywood. It made its first flight in Yangling, without weapons, and being destroyed during the landing.

XP-0 technical data

Wingspan: 11.4 m, length: 8.8 m, height: 3.70 m, wing area: 22 sq.m, max weight: 2,990 kg, estimated max speed: 504 kph, range 1,400 km, armament: four 20 mm Hispano cannons mounted in the wings.

The next attempt, called XP-1, was designed in 1942 by Constantin Zakharchenko and built in Guiyang in 1944. It also being destroyed during its first flight, with fixed undercarriage, on January 1945. The XP-1 was powered by one 1,200 hp Wright Cyclone R-1820-71 from one C-49D. It had wood/plywood inverted-swept wings, with automatic flaps, and the fuselage was built in steel tube/fabric.

XP-1 technical data

Wingspan: 12.10 m, length: 8.72 m, max weight: 2,930 kg, estimated max speed: 580 kph, armament: two 12.7 mm machine guns in the wings.

In the meantime, the availability of advanced U.S. fighters had removed the need for Chinese indigenous fighters and further development was discontinued.

Books

Cheung, R., Aces of the Republic of China Air Force, Osprey aircraft of the Aces 126, 2015.

Cuny, J., Curtiss Hawk 75, DOCAVIA nº 22, Editions Lariviere, 1985.

Green, W., The Complete Book of Fighters, Salamander Books, 2001.

Bowers, P., Curtiss Navy Hawks in action, nº 128, Squadron/Signal publications, 1992.

Apostolo, G., Fiat C.R.32, Ali d’Italia 4, La Bancarella Aeronautica, 1996.

Publications

O’Leary, M., ‘Boeing P-26 Peashooter’, Aeroplane, August 2006.

Sakaida, H., ‘La Guerre des deux Soleils 1937-1941’, le Fanatique de l’Aviation, Juillet 1996.

Demin, A., ‘Soviet Fighters in the Sky of China’, Aviatsiia Kosmonavtika, 2000.

Demin, A., ‘Changing from Donkeys to Mustangs’, Aviamaster 6/2000, Twin Cities Aero Historians.

Anderson, L., ‘Chinese Junks’, Air Enthusiast/Autumm 1994.

Hooton, E., ‘Airwar Over China’, Air Enthusiast/Thirty-Four.

Johnson, R. ‘Before the Tigers: China’s Air Forces in the Struggle Against Japan’, http://worldatwar.net/chandelle/v2/v2n2/china30s.html

Hackett, B., ‘Rising Storm-The Imperial Japanese Navy and China 1931-1941’, http://www.combinedfleet.com/Rising.htm 2012

Gustavsson, H., ’Sino-Japanese Air War 1937-1945’

http://surfcity.kund.dalnet.se/sino-japanese-1937.htm

CW-21 technical data

Wingspan: 10.66 m, length: 8.03 m, height: 2.60 m, wing area: 16.19 sq.m, max weight: 1,896 kg, maximum - speed: 476 kph, range: 853 km, power plant: one 1,000 hp Wright Cyclone R-1820-G5 air-cooled radial engine.

The contract with the firm Curtiss included the import of an H-75Q and components for the manufacture of forty-nine H-75Q in CAMCO. Unfortunately for the Chinese, the Zero could fly for 3,100 km, remaining more than 8 hours in the air. This capacity allowed them to escort the G3M2 to the most remote sanctuary-bases of the C.A.F. preventing its annual re-organization

On May 1940 the G3M2 Model 22 started to be used in China. They used oxygen equipment and 87 octane fuel to fly at 7,000 m, attacking the Chinese airfields with the new bombs Type 2, Mk 21 of 52.5 kg. Each of them consisting of a canister containing thirty-six H.E. submunitions. The G3M2 used to operate in collaboration with the Mitsubishi C5M2 Type 88 fast reconnaissance airplanes that informed them by radio when the Chinese fighters landed for refuelling.

During August the IJA continued the attacks against Kunming and Chengtu using the new Mitsubishi Ki.21 bombers. Between 19 August 1940 and 15 September 1941 the Zeros downed 103 planes of the C.A.F. and destroyed other 162 in strafing missions. The Soviets tried to fight the Zeros using mixed formations of I-153, I-16 Type 10 and Type 17 fighters flying in three levels at 7,500 m, 7,000 m and 6,500 m.

After numerous tests with an A5M2 captured in China, the Soviets came to the conclusion that the Polikarpov I-153 (444 kph) were more capable of tracking the Japanese monoplane on equal terms.

The I-153 was as fast as the I-16 Type 6, its climb rate the highest of all Soviet fighters and its gull wing configuration allowed it to turn 360 degrees in 13.3 seconds, without losing height at every turn. It was very well armed with four rapid-fire ShKas machine guns and equipped with a PAK-1 reflex gunsight, oxygen, armour plates and RSI-3 R/T device. The I-16 Type 17 was more slow, with a rate of climb of just 9.4 m/sec (the Zero had 15.75 m/sec) consequence of the additional weight of the two 20 mm ShVAK cannons and their ammunition.

The Soviets considered this armament was necessary to combat the new G4M1 weapons bombers. But it turned out that both the Zero and the G4M1 were equally armed with cannons and the Japanese fighter not only was 100 kph faster than the I-153, but it could also turn on only 11.2 seconds.

Confronted with the Zero, the Polikarpov I-153 could not flee and, if they decided to fight, they were systematically shot down. On 14 March 1941, in their first combat over Shuang-Liu airfield, the I-153 lost 13 to 0. After this last failure, the USSR decided to abandon the China adventure to concentrate on defending its European borders.

Foreign observers doubted the combat potential of the C.A.F. remaining force. On April 1941 the situation alarmed the US Administration, who authorized the creation of the A.V.G., an expeditionary force consisting of three squadrons of Curtiss P-40B (566 kph) Flying Tigers. On August the U.S. Administration imposed an oil embargo on Japan and the 87-octane gasoline would no longer available.

On September, the IJN started to concentrate its forces in Japan and Taiwan to prepare the attack against Philippines and Pearl Harbour. Until then, the Japanese losses were of 287 aircraft shot down in combat and 100 in accidents. Those of the C.A.F. were 355 aircraft downed and 1,230 in strafing and accidents. By early November the C.A.F. had been reduced to 29 fighters, 60 bombers and 42 various other aircraft.

After the destruction of the only Curtiss ‘Interceptor’ available in China, the A.V.G. had no means to intercept the high-flying Mitsubishi Ki.46-II Dinah reconnaissance airplanes from the IJA 8th Sentai. To provide high-altitude cover to the slow P-40B, the U.S. Administration authorized the export to China of seventy-two fighters Republic P-43 ‘Lancer’ and hundred-and-eight P-43 A-1‘Chinese Lancer’, through Lend-Lease Act.

The long sea voyage damaged the Fairplane cement used to seal the wing fuel tanks, a circumstance that went unnoticed during its assembly in India and that caused the loss of 139 aircraft during the Karachi-Chengtu ferry flight. Most of the accidents were fires caused by the fuel dripping under the fuselage belly until reaching the hot turbo-exhaust.

On July 1942, ten P-43A were delivered to the A.V.G. The turbo-supercharger provided the Lancer good power through 9,000 m and American pilots who tested it in flight were satisfied with its good handly and rapid rate of roll, but the A.V.G. staff did not trust them as interceptors and chose to use them as reconnaissance airplanes. However, one of them managed to shoot down a Dinah over Bhamo.

The P-43 A-1 were used by the C.A.F. against the Ki.46, with little success, since both models had the same speed at 6,000 m. On 24 October 1942, the 24th Sqn ‘Chinese Lancers’ downed a Dinah, from 18th Dokuritsu Chutai, over Si Bao and one Kawasaki Ki.48 from 16th Sentai over Han-Sou on 12 January 1943.

The turbo-supercharger was a complex piece of equipment and the C.A.F. simply did not have the resources to train people to properly maintain the units. The P-43 A-1 had a limited use in combat and the Dinah completely lost its immunity only when the Lockheed P-38 began operating in the Far East.

P-43 A-1 technical data

Wingspan: 10.97 m, length: 8.68 m, height: 4.26 m, wing area: 20.72 sq.m, max weight: 3,846 kg, max speed: 573 kph, range: 2,333 km, power plant: one 1,200 hp Pratt & Whitney R-1830-57 air-cooled radial engine, armament: two 12.7 mm heavy machine guns mounted in the cowl and two 12.7 mm in the wings.

In 1939 the firm Vultee Aircraft developed the Model 48C, a monoplane light fighter based on the airframe of the Valiant trainer.

On 6 February 1940 the Swedish government ordered 144 fighters Vultee Model 48C but, fearing that the airplanes might fall into Soviet hands, the U.S. State Department placed an embargo on the export of military aircraft to Sweden in October 18. On February 1942 the Roosevelt Administration allowed the export to China via Karachi of 119 fighters Model 48C, under the designation P-66 ‘Vanguard’.

They fought against the Ki.48 Type 99 bombers of the 90th Sentai and their escort fighters Nakajima Ki.43-I east of Enshih airfield on 6 June. In August, twenty-one Type 97 bombers from 58th Sentai performing a raid over Chungking, escorted by thirty-one Ki.43-I from 25th and 33rd Sentais, were intercepted by ten P-40B, eight P-43 A-1 and eleven P-66. Two ‘Vanguards’ were shot down by the Nakajima fighters.

On October 1942, the C.A.F. tried to use them against the Dinah, again without any success. In China, the ‘Vanguard’ did exhibit some handling problems during high speed dives, poor lateral stability and undesirable stalling characteristics during landing. Corrosion problems resulting from an inadequate maintenance of the weak landing gear, caused frequent ground loops and broken tailwheels. On December 1943 the 53 serviceable Vanguards were removed from to combat status and used only for training duties.

P-66 technical data

Wingspan: 10.97 m, lenght: 8.66 m, height: 2.87 m, wing area: 18.30 sq.m, max weight: 3,221 kg, max speed: 574 kph, range: 1,386 km, power plant: one 1,200 hp Pratt & Whitney R-1830-33 air-cooled radial engine, armament: two 12.7 mm heavy machine guns mounted in the cowl and four 7.62 mm in the wings.

At the time of their acquisition the Polikarpov I-16 Type 5, the Dewoitine D.510C, the Curtiss H-75M, the Curtiss CW-21, the Republic P-43 and the Vultee P-66 were considered 'Panic Fighters' although none of them managed to overcome its Japanese equivalents in this long war. But the real Chinese 'Panic Fighters' were some indigenous aircraft designed and built in desperate circumstances.

At the beginning of 1937, the designer Chee Wing Jeang built the Kwangsi Type 3, a biplane fighter developed at the Liuchow Mechanical Aircraft Factory for the Kwangsi Independent Air Force. The only prototype was built with wood/plywood wings and steel-tube/fabric fuselage. It flew for the first time on July, powered by a 260 hp Armstrong Siddeley Cheetah IIA air-cooled radial engine. Its performances proved insufficient to justify further development.

Kwangsi Type3 technical data

Wingspan: 8.0 m, length: 6.25 m, height: 2.5 m, wing area: 22 sq.m, max weight: 1,043 kg, max speed: 283 kph, rate of climb: 5.28 m/sec, armament: one 7.7mm machine gun synchronized with the propeller.

In the summer of 1937 Japanese bombers bombarded the Shaoguan Aircraft Factory, where the Hawk III fighters were assembled, and the Factory was moved to Hangzhou. But it was also bombed there before entering service. Production continued in the First Aircraft Factory of Kun-Ming in Yunnan Province in 1938. After a new attack they moved to Loiwing by mid-1939, but the new location was destroyed in the bombing of 26 October 1940 and occupied by Japanese troops on May 1942.

In 1943 the Aircraft Factory was dispersed in several locations, around Kun-Ming, where seven Hawk 75 A-5 and two CW-21 were built using parts recovered from the destroyed factories. The Aviation Research Institute was installed in one Yangling cave, where General Major Chu Chia-Jen designed the new Chinese XP-0 fighter in 1941.

A unique prototype was manufactured in 1943 by AFAMF-Yangling, using the tail surfaces of a Hawk 75, the centre section of the wing and the landing gear of a North American NA-6, the tailwheel from P-43 and the engine and cockpit of a P-66. The wings were built in wood/plywood. It made its first flight in Yangling, without weapons, and being destroyed during the landing.

XP-0 technical data

Wingspan: 11.4 m, length: 8.8 m, height: 3.70 m, wing area: 22 sq.m, max weight: 2,990 kg, estimated max speed: 504 kph, range 1,400 km, armament: four 20 mm Hispano cannons mounted in the wings.

The next attempt, called XP-1, was designed in 1942 by Constantin Zakharchenko and built in Guiyang in 1944. It also being destroyed during its first flight, with fixed undercarriage, on January 1945. The XP-1 was powered by one 1,200 hp Wright Cyclone R-1820-71 from one C-49D. It had wood/plywood inverted-swept wings, with automatic flaps, and the fuselage was built in steel tube/fabric.

XP-1 technical data

Wingspan: 12.10 m, length: 8.72 m, max weight: 2,930 kg, estimated max speed: 580 kph, armament: two 12.7 mm machine guns in the wings.

In the meantime, the availability of advanced U.S. fighters had removed the need for Chinese indigenous fighters and further development was discontinued.

Bibliography

Books

Cheung, R., Aces of the Republic of China Air Force, Osprey aircraft of the Aces 126, 2015.

Cuny, J., Curtiss Hawk 75, DOCAVIA nº 22, Editions Lariviere, 1985.

Green, W., The Complete Book of Fighters, Salamander Books, 2001.

Bowers, P., Curtiss Navy Hawks in action, nº 128, Squadron/Signal publications, 1992.

Apostolo, G., Fiat C.R.32, Ali d’Italia 4, La Bancarella Aeronautica, 1996.

Publications

O’Leary, M., ‘Boeing P-26 Peashooter’, Aeroplane, August 2006.

Sakaida, H., ‘La Guerre des deux Soleils 1937-1941’, le Fanatique de l’Aviation, Juillet 1996.

Demin, A., ‘Soviet Fighters in the Sky of China’, Aviatsiia Kosmonavtika, 2000.

Demin, A., ‘Changing from Donkeys to Mustangs’, Aviamaster 6/2000, Twin Cities Aero Historians.

Anderson, L., ‘Chinese Junks’, Air Enthusiast/Autumm 1994.

Hooton, E., ‘Airwar Over China’, Air Enthusiast/Thirty-Four.

Johnson, R. ‘Before the Tigers: China’s Air Forces in the Struggle Against Japan’, http://worldatwar.net/chandelle/v2/v2n2/china30s.html

Hackett, B., ‘Rising Storm-The Imperial Japanese Navy and China 1931-1941’, http://www.combinedfleet.com/Rising.htm 2012

Gustavsson, H., ’Sino-Japanese Air War 1937-1945’

http://surfcity.kund.dalnet.se/sino-japanese-1937.htm

bunnystar211

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 22 April 2019

- Messages

- 33

- Reaction score

- 42

thanks

thanks your information, that too much, i need to read it.From the book "Enemy at the gates, panic fighters of the WWII"

China (28 January 1932 to August 15 1945)