You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Canadair CL-41 Projects

- Thread starter hesham

- Start date

- Joined

- 25 July 2007

- Messages

- 4,299

- Reaction score

- 4,189

Re: Canadair CL-41R project

According to Pickler/Milberry, there were 28 unbuilt CL-41 variants. Unfortunately no details are listed. However, there are a few hints in designations and powerplants.

Since the Tebuan was a CL-41G-5, obviously at least four other CL-41Gs were planned. Flight reports that a CL-41G model was Canadair's specific proposal for Joint RAAF-RNZAAF trainer. Engine options give futher hints to planned variants.

Initial CL-41 planning was for the AS Viper engine (presumably the ASV.10 since a Viper 5 wouldn't have enough thrust). Among engine options, Flight says that "Production versions, the company state, can be supplied with either the Fairchild J83, General Electric J85, Pratt and Whitney JT-12 or Armstrong Siddeley Viper, and a version of the Rolls-Royce RB.108 has also been proposed."

http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1958/1958-1-%20-%200262.html

Flight even stated erroneously that the two CL-41 prototypes would fly with Fairchild J83s (speculating that Orenda would build the J83s if that engine was chosen by the RCAF).

Flight mentions other engine options: "Production versions, the company state, can be supplied with either the Fairchild J83, General Electric J85, Pratt and Whitney JT-12 or Armstrong Siddeley Viper, and a version of the Rolls-Royce RB.108 has also been proposed."

http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1958/1958-1-%20-%200262.html

According to Pickler/Milberry, there were 28 unbuilt CL-41 variants. Unfortunately no details are listed. However, there are a few hints in designations and powerplants.

Since the Tebuan was a CL-41G-5, obviously at least four other CL-41Gs were planned. Flight reports that a CL-41G model was Canadair's specific proposal for Joint RAAF-RNZAAF trainer. Engine options give futher hints to planned variants.

Initial CL-41 planning was for the AS Viper engine (presumably the ASV.10 since a Viper 5 wouldn't have enough thrust). Among engine options, Flight says that "Production versions, the company state, can be supplied with either the Fairchild J83, General Electric J85, Pratt and Whitney JT-12 or Armstrong Siddeley Viper, and a version of the Rolls-Royce RB.108 has also been proposed."

http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1958/1958-1-%20-%200262.html

Flight even stated erroneously that the two CL-41 prototypes would fly with Fairchild J83s (speculating that Orenda would build the J83s if that engine was chosen by the RCAF).

Flight mentions other engine options: "Production versions, the company state, can be supplied with either the Fairchild J83, General Electric J85, Pratt and Whitney JT-12 or Armstrong Siddeley Viper, and a version of the Rolls-Royce RB.108 has also been proposed."

http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1958/1958-1-%20-%200262.html

meredithwill

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 8 August 2024

- Messages

- 3

- Reaction score

- 4

Was there any consideration or speculation about converting the Canadair Tutor from trainer to attack aircraft similar to what was done with the Cessna Tweetybird to Dragonfly?

- Joined

- 26 May 2006

- Messages

- 34,828

- Reaction score

- 15,709

Welcome aboard,

you must see this topic,

you must see this topic,

- Joined

- 29 July 2009

- Messages

- 1,767

- Reaction score

- 2,456

- Joined

- 29 July 2009

- Messages

- 1,767

- Reaction score

- 2,456

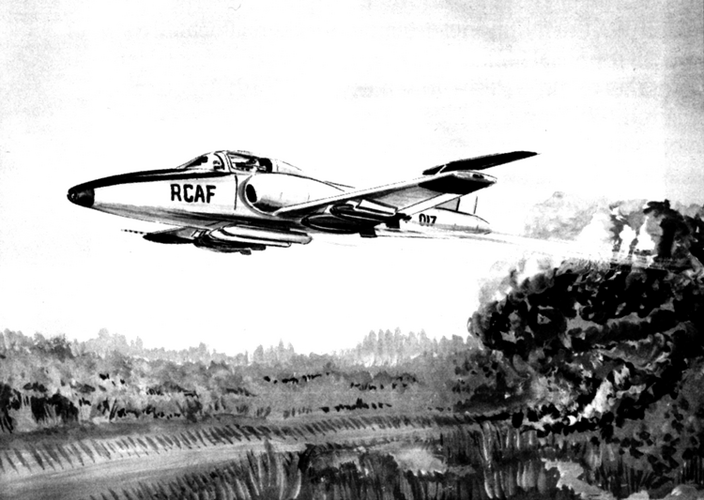

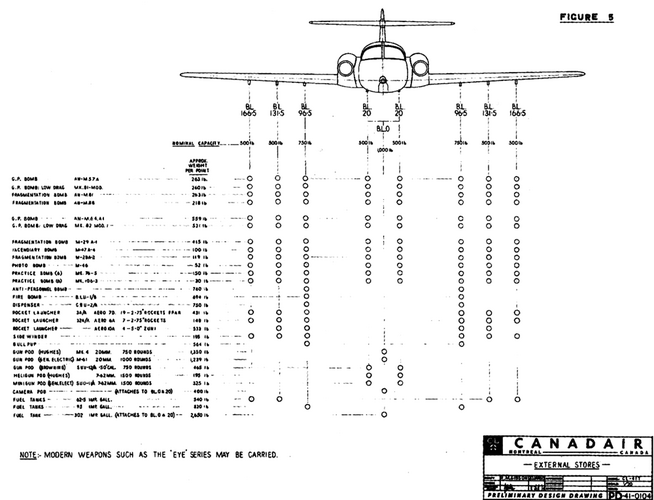

Malaysia called it the Tebuan:CL-41G is a combat variant of the CT-114. Only Malaysia took up the CL-41G aircraft as an attack/trainer aircraft.

Attachments

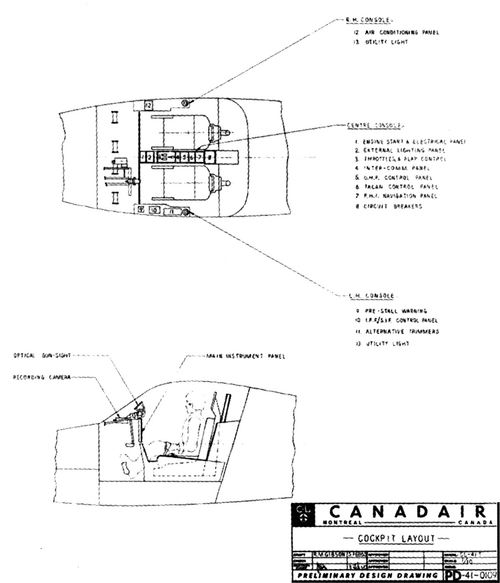

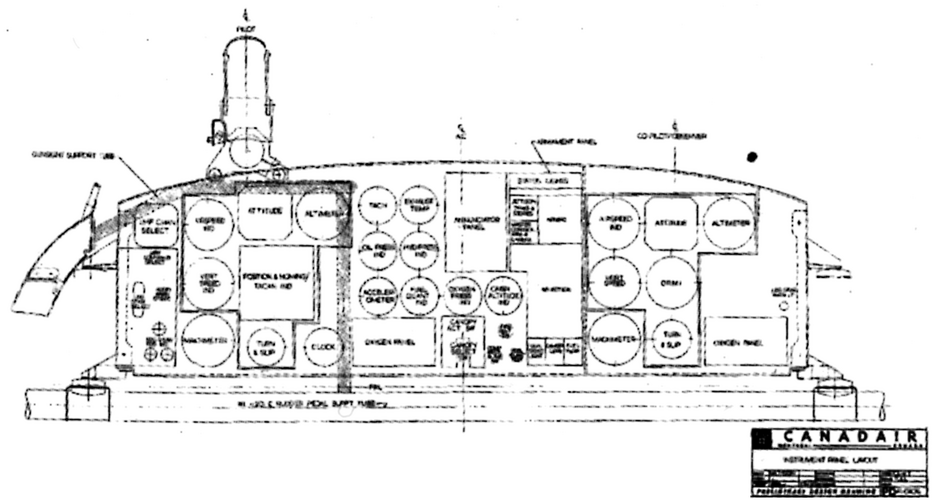

Canadair designed a ground attack version of the CL-41 in part because it was aware of what is happening on the international scene, decolonisation and conflicts in Africa and Asia for example. The Quebec firm and its parent company, General Dynamics, (briefly?) considered the possibility of producing in the United States some, many or most of the aircraft that the American government might order - and possibly donate to friendly countries. A prototype of the "Shooter Tutor" flew in June 1964. A series of demonstration flights in South America carried out subsequently did not lead to a single order. In 1966, however, the Malaysian Air Force acquired twenty CL-41Gs which entered service from May 1967 onward.

Some background info on the CL-41...

The Royal Canadian Aviation (RCAF) began to consider replacing its Lockheed/Canadair T-33 Silver Star trainers in the mid-50s. In 1956, for example, it became increasingly interested in a concept put forward by the RAF: all-through jet training. The RCAF actually considered the possibility of proposing that a Canadian firm acquire the production rights for the Hunting Percival Jet Provost, the aircraft which was to be used by the RAF. Quebec-based Canadair hoped to land that potential order.

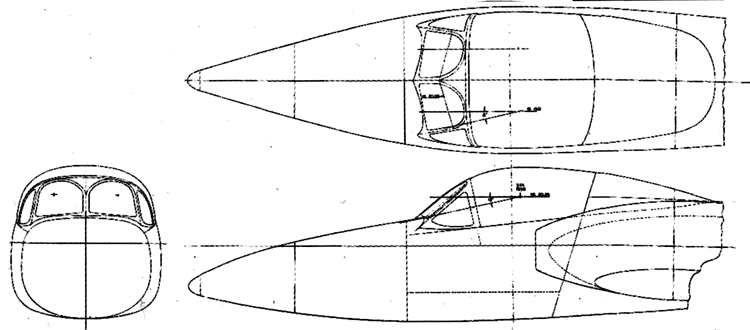

This project having fallen by the wayside, Canadair changed its strategy. One project in particular was gaining support: the design and production of a jet trainer. Management weighed the pros and cons; there were many risks in such a private venture. In late 1957, Canadair began to work on that jet trainer, its first fully original design.

In the summer of 1958, the Budget Sub-Committee of the House of Commons voted in favour of all-through jet training. Even so, the RCAF was in no hurry to choose an aircraft, which suited Canadair just fine. Indeed, its CL-41 benefited from what the firm could learn about similar aircraft under development elsewhere. The CL-41 was in fact designed to meet the requirements of the RCAF, RAF and U.S. Air Force.

In any event, there were several factors which contributed to significant delay in the modernisation of RCAF equipment, from the problems surrounding the development of the Avro CF-105 Arrow all-weather supersonic fighter aircraft to the reequipment of Canadian squadrons stationed in Western Europe.

Canadair preferring to concentrate its efforts on slightly less risky projects than its private venture trainer, the reequipment the squadrons stationed in Western Europe for example, the prototype of the CL-41 only flew in January 1960. By then, the RCAF was becoming more and more interested in that machine because some of its flying schools still used outdated piston-powered North American Harvards. Unfortunately for the RCAF and Canadair, the federal government was keen to control its expenditures. It did not want to buy new aircraft.

Months went by. In August 1961, Canadair decided to undertake a promotional tour in Europe. The CL-41 prototype flew in several NATO member countries (West Germany, Netherlands, Belgium) as well as in Switzerland and Sweden. In September, before the return of the aircraft, the RCAF announced its intention to purchase 190 Canadair CL-41s, to be designated CT-114 Tutors.

There was still a catch, however. The parties could not agree on which engine to use. The Department of National Defence favoured the General Electric J85 while Canadair favoured the engine which powered its prototype, the Pratt & Whitney JT12, an engine originally developed by Quebec-based Canadian Pratt & Whitney Aircraft. The Department of Defence Production organised a competition in the fall of 1961. A lengthy review process began.

Months went by. In the meantime, many Canadair workers lost their jobs. Their furious union representatives visited the Minister of Defence Production in March 1962. Raymond O'Hurley reassured them; a decision was coming. Days went by. You see, the Tutor’s production project was going through a difficult period. All potential customers in Europe had withdrawn and an increasingly concerned Treasury Board suggested to the Cabinet that the CL-41 be abandoned.

The Department of Defence Production announced its decision in May 1962, a month or so before a federal election. The Tutors would be powered by J85s made under license in Ontario by the Orenda Division of Hawker Siddeley Canada. This eminently political decision allowed the government to share the pie between Quebec and Ontario.

Canadair delivered the first Tutor in December 1963.

By then, the party in power in May 1962 had been relegated to the status of official opposition. It would remain in that position between April 1963 and September 1979

The Royal Canadian Aviation (RCAF) began to consider replacing its Lockheed/Canadair T-33 Silver Star trainers in the mid-50s. In 1956, for example, it became increasingly interested in a concept put forward by the RAF: all-through jet training. The RCAF actually considered the possibility of proposing that a Canadian firm acquire the production rights for the Hunting Percival Jet Provost, the aircraft which was to be used by the RAF. Quebec-based Canadair hoped to land that potential order.

This project having fallen by the wayside, Canadair changed its strategy. One project in particular was gaining support: the design and production of a jet trainer. Management weighed the pros and cons; there were many risks in such a private venture. In late 1957, Canadair began to work on that jet trainer, its first fully original design.

In the summer of 1958, the Budget Sub-Committee of the House of Commons voted in favour of all-through jet training. Even so, the RCAF was in no hurry to choose an aircraft, which suited Canadair just fine. Indeed, its CL-41 benefited from what the firm could learn about similar aircraft under development elsewhere. The CL-41 was in fact designed to meet the requirements of the RCAF, RAF and U.S. Air Force.

In any event, there were several factors which contributed to significant delay in the modernisation of RCAF equipment, from the problems surrounding the development of the Avro CF-105 Arrow all-weather supersonic fighter aircraft to the reequipment of Canadian squadrons stationed in Western Europe.

Canadair preferring to concentrate its efforts on slightly less risky projects than its private venture trainer, the reequipment the squadrons stationed in Western Europe for example, the prototype of the CL-41 only flew in January 1960. By then, the RCAF was becoming more and more interested in that machine because some of its flying schools still used outdated piston-powered North American Harvards. Unfortunately for the RCAF and Canadair, the federal government was keen to control its expenditures. It did not want to buy new aircraft.

Months went by. In August 1961, Canadair decided to undertake a promotional tour in Europe. The CL-41 prototype flew in several NATO member countries (West Germany, Netherlands, Belgium) as well as in Switzerland and Sweden. In September, before the return of the aircraft, the RCAF announced its intention to purchase 190 Canadair CL-41s, to be designated CT-114 Tutors.

There was still a catch, however. The parties could not agree on which engine to use. The Department of National Defence favoured the General Electric J85 while Canadair favoured the engine which powered its prototype, the Pratt & Whitney JT12, an engine originally developed by Quebec-based Canadian Pratt & Whitney Aircraft. The Department of Defence Production organised a competition in the fall of 1961. A lengthy review process began.

Months went by. In the meantime, many Canadair workers lost their jobs. Their furious union representatives visited the Minister of Defence Production in March 1962. Raymond O'Hurley reassured them; a decision was coming. Days went by. You see, the Tutor’s production project was going through a difficult period. All potential customers in Europe had withdrawn and an increasingly concerned Treasury Board suggested to the Cabinet that the CL-41 be abandoned.

The Department of Defence Production announced its decision in May 1962, a month or so before a federal election. The Tutors would be powered by J85s made under license in Ontario by the Orenda Division of Hawker Siddeley Canada. This eminently political decision allowed the government to share the pie between Quebec and Ontario.

Canadair delivered the first Tutor in December 1963.

By then, the party in power in May 1962 had been relegated to the status of official opposition. It would remain in that position between April 1963 and September 1979

Last edited:

Similar threads

-

Canadair/General Dynamics CL-84 Projects

- Started by overscan (PaulMM)

- Replies: 118

-

-

-

-