For comparison:

There is too much "noise" between data from totally different engines for this to pick up something like a 5>20% change in fuel economy, I have been attempting to

say this for several posts. The only way to do this is to get two engines which are basically identical and do a with carburettor / with DI.

A good example of this is the DB600, which early versions had carburettors from about 1931>1934 and the first experimental version with D.I. in 1934.

Luckily I have the datasheets for both engines from Daimler-Benz AG corporate archives in Germany, I think this is about as good a comparator basis as is

possible with aero engines of that era (similar will exist for the Jumo210, but I dont think I have the datasheets at hand for that sadly, as the Jumo documents

are less well preserved than Daimler - another mystery for discussion !). These engines also had the same compression-ratio (6.5:1), which is utterly fundamental to

fuel economy.

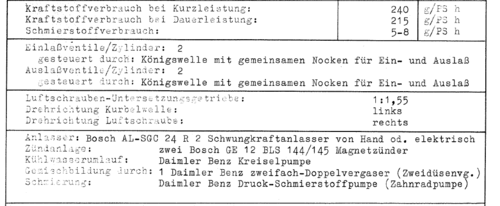

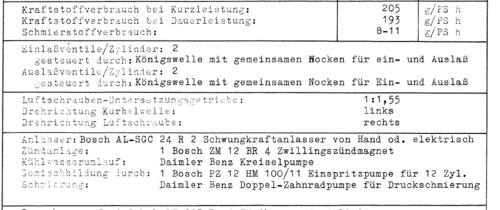

(DB archive ref "DBAG DB 2MA-121")

Not sure what your German is like, but you must be reasonable if reading the FT documents, but for everyone else "Doppelvergaser" = Twin-Carburettors

and "Einspritz" = Injection (lower pic = DB600 prototype with injection, Upper pic = DB600 prototype with carburettors).

Gain is 17% better economy at full boost and 11% better at max economy with D.I over the

carburettor.

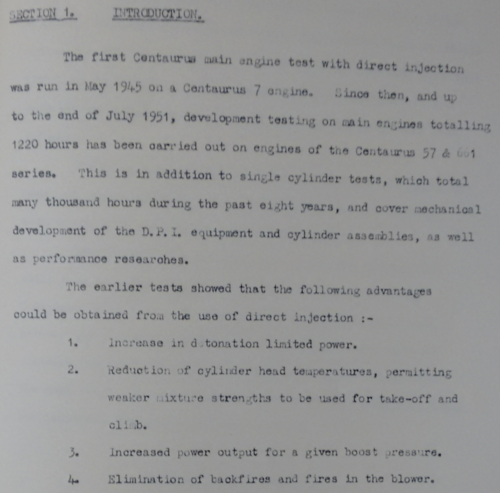

As for Radials and Bristol, Bristol put Direct Injection on the Civil-Centaurus (661) in late 1945, and found it

exceptionally advantageous. (I have the Bristol documents from Rolls-Royce Bristol archives). The best improvments were at high boost, with a

large gain in economy at max boost, and only slight at the lowest boost setting.

0.965 > 0.870 pints/bhp/hr @55.5 " HG boost 2800rpm (10% better economy)

0.540 > 0.536 " " @37" HG Boost 2500rpm (1% better economny

(Point #2 relates to the better fuel economy).

You can see there is no "rule" for the gain you`ll get, and its totally dependant on each individual

engine, its thermal and combustion characteristics. The DB has a min gain of 11%, the centaurus

just 1%, so you can see how if you use a different engine to try to compare DI to Caburettor

or single point injection, you can easily see such differences vanish in the noise. They can only

be seen reliably in data such as these tests where you convert an existing engine which is

otherwise identical from one system to the other.

Now, without just posting my entire book here in this thread just to satisfy you, thats where I`m leaving this matter as closed. If you wish

to carry on with your original views thats totally alright.