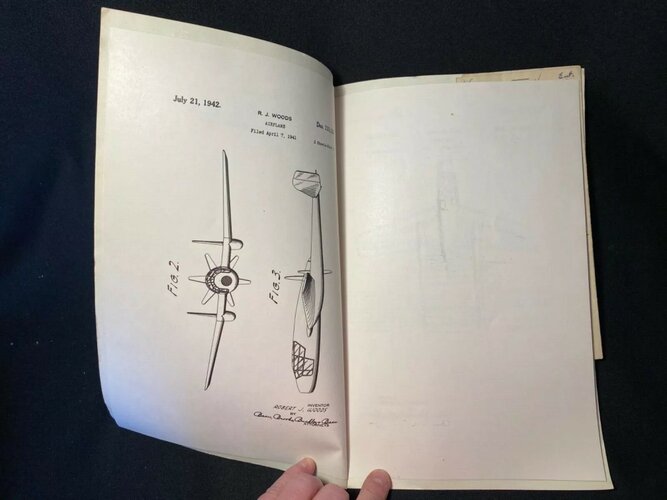

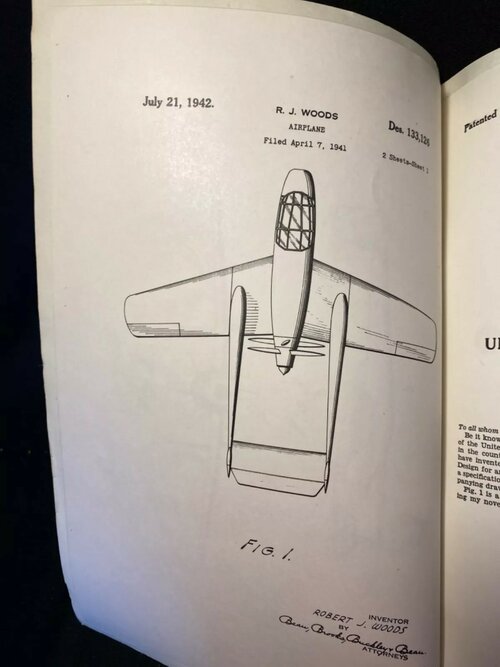

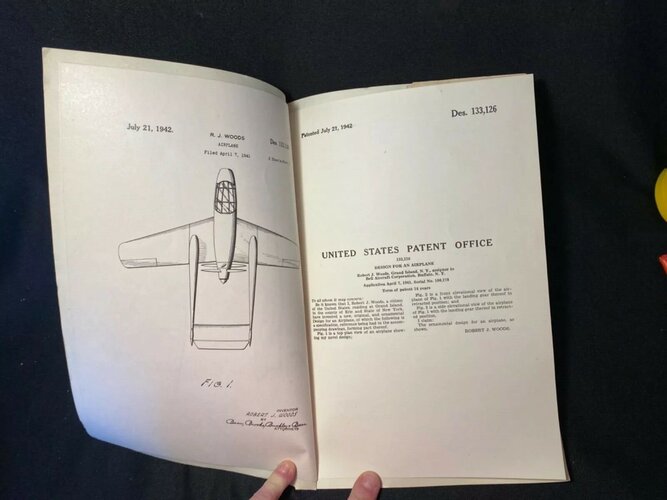

Japanese Shinden suffered many of the same problems as the contemporary Curtiss Ascender.

First, the propeller worked in turbulent air coming off the fuselage.

Secondly, lowering flaps meant even more turbulent air hitting the propeller.

Thirdly, both air planes suffered balance problems, compounded by canards that were too small.

Fourthly, rudders were too small and mounted on moments that were too short.

Fivethly, designers failed to compensate for P-factor, which means the the descending propeller blade hits the air at a steeper angle of attack, creating more thrust on one side and trying to turn the airplane. P-factor is worst while climbing. Since Shinden's propeller rotated counter-clockwise (as seen from the rear), it imparted a right-turning tendency.

Shinden had difficulty raising its nose for take-off because the canard was too small and at too shallow an angle of attack.

P-factor (asymmetric thrust) soon over-whelmed rudder authority and aileron authority, giving Shinden a difficult, right-turning tendency.

During the 1970s, Burt Rutan solved those problems by shifting centre of gravity forward to load the (larger) canard more heavily. Rutan also mounted rudders farther aft on swept wings or long tail booms. The end result was Rutan canards that cruised very efficiently, but were not extremely maneuverable.