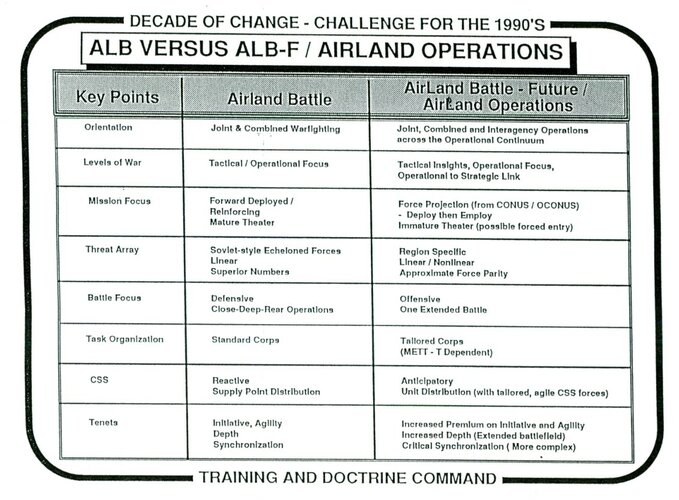

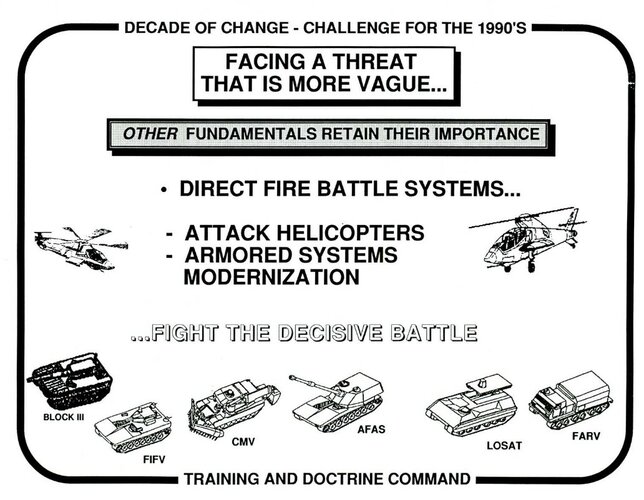

TAC-TRADOC collaboration reflected the two services' recognition of their mutual interdependence in modern warfare and their need to establish commonly understood procedures for cooperation in a variety of tactical functions. An important first step was to develop a common vision of the future battlefield, a step taken as the Air Force participated with the Army in developing scenarios at Fort Leavenworth. Implicit here was the growing realization that combat on land was not an autonomous activity sometimes supported by air operations but that ground and air operations were integral, inseparable parts of the whole effort to apply force against and defeat the enemy. Inspired by Major General Cushman, who wrote about air-ground integration as early as 1965, officers at Fort Leavenworth began to use the terms "air-land" and "air-land battle" to express this idea. While the component parts of air-land battle (air defense, tactical air support, and airspace management) were not new problems to officers of either service, a heightened consciousness of their importance and the difficulties inherent in synchronizing them with traditional missions of both services suggested the need for a new, three-dimensional concept of the battlefield. Thus, Major General Cushman included a chapter titled "Air/Land Operations" in the draft of FM 100-5 that he prepared for the first meeting at Fort A. P. Hill, implying that this new concept was as important to the Army's thinking about warfare as were the concepts of offense, defense, and intelligence, the subjects of other chapters. Cushman described the inherent problems of the air-land battle concept: "The basic problem facing the air and land commanders is to work together so that each part of the air/land force can operate to its full potential without needlessly restricting the operations of any other part. The combined air/land battle force that solves this problem best will most likely prevail."32

Major General Cushman's version of FM 100-5 did not survive that first meeting, but ideas about air-land battle did. Using a team composed of officers from the USACGSC student body, CACDA, and the TAC liaison office to CAC, Cushman prepared a briefing on the air-land battle concept and presented it to TAC and TRADOC staff officers in March and April 1975. The concept posited a corps-size Army element with appropriate Air Force support in a scenario set in the Middle East and attempted to portray a "conceptualization of the integrated Air-Land tactical battle." Despite some initial misgivings by the TAC staff members, Major General Cushman and his team briefed Generals DePuy and Dixon on 10 April 1975.33

DePuy and Dixon expressed reservations about the concept. They believed the concept implied a misuse of tactical air support assets, calling for flights of two aircraft for missions requiring a hundred. Furthermore,they doubted that the joint combat operations center called for in the briefing would work. They sent the briefing team back to Fort Leavenworth with a new set of instructions for developing the concept further and postponed staff work on a proposed joint memorandum of agreement on air-land battle.34

Major General Cushman's concept of air-land battle did not become an agreed-on doctrine of the U.S. Army and Air Force in the spring of 1975, but the reasons transcend Generals Dixon and DePuy's reservations expressed at the briefing. First, the TAC staff officers who heard the pre-briefing were not enthusiastic about the concept from the beginning. They believed it dealt with too many specific details, required decisions from the TAC commander that he was not yet prepared to make, and reflected a misunderstanding of the current Air Force Air-Ground Operations System. These misgivings, combined with the reservation that the concept misused tactical aircraft, suggested considerable Air Force opposition to the concept.

Second, Cushman did not have DePuy's full confidence in the spring of 1975. One almost feels the clash of the two men's personalities in the brief notes recording the instructions given the briefing team after their presentation: "Reorient [the] effort to align with substantive problems: Winning the war tomorrow ... Europe present forces ... Limited to defense suppression. "Finally, what Cushman suggested to DePuy and Dixon was a substantive change in doctrine, and they had agreed to coordinate procedures only, not doctrine.

This last point is a fine one because, as we have seen, all parties agreed on the component issues of air-land battle. However, Major General Cushman was urging that both services agree that these issues constituted the core of battle as it would occur in the foreseeable future. Purely air or ground roles would be the exception and would take second priority to articulating the doctrine and equipping, training, and fielding the forces necessary for the air-land fight. For this reason, a joint task force commander of either service needed his own combat operations center with which to control the unified battle on the ground and in the air, to include controlling the assets of both services. Neither service was yet willing to go that far because, to do so, could require significant redefinition of service roles and apportionment of assets. By rejecting Cushman's air-land battle concept, Generals DePuy and Dixon agreed on a safer, more productive approach: tacit acceptance of two arenas of battle, one on the ground and one in the air, each the primary province of a respective service, and explicit acknowledgment that the two arenas are mutually interdependent, leading to procedural, but not doctrinal, collaboration. Rather than serving as a platform for doctrinal revolution, the TAC-TRADOC dialogue of the mid-1970s reflected an unprecedented degree of Army-Air Force cooperation in peacetime.