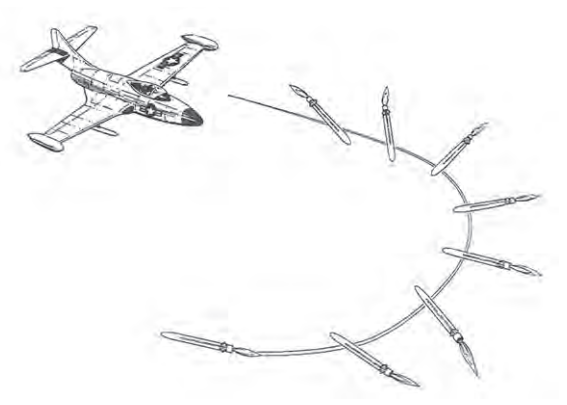

The third application of TVC was investigated with Project Quickturn. Air-to-air missiles are launched at relatively high speeds, and turning the missile quickly after launch offers a huge tactical advantage to the shooter. However, aerodynamic control surfaces do not provide the desired maneuverability when the launched missile’s speed is only slightly above the speed of the launching aircraft. TVC has the ability to change the heading of a missile 180 degrees in seconds, which dramatically improves the ability of the missile to intercept targets at high off-boresight angles. This application was still a high risk technology, because the missile would be nearly always in an aerodynamically unstable state.

[..]

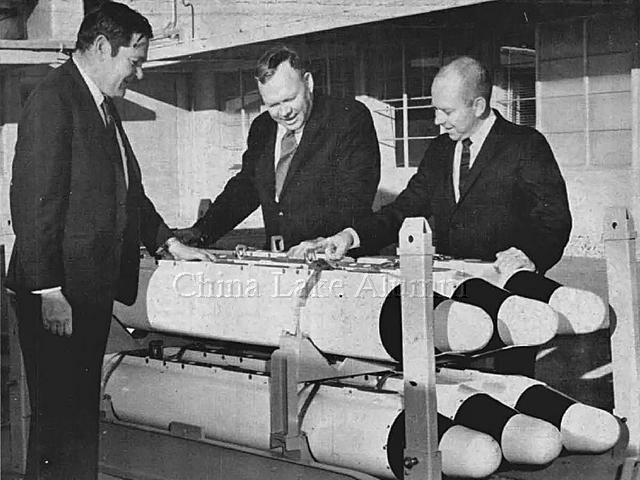

Leroy J. Krzycki, head of the Propulsion Development Department’s Engineering Applications Branch, set up the Quickturn program. “He got a lot of quick support directly out of NAVAIR for the innovative and creative things he was talking about doing,” said Bob Dillinger, head of the Propulsion Components Branch (later renamed the Systems Technology Branch).

“He was the kind of guy that would give you a job to do and if you didn’t have it done in 3 days, he’d do it himself.”

In 1969, NWC tested two Thiokol Chemical Corp. gimbaled nozzles and two Lockheed Propulsion Co. flex-seal nozzles. Jim Andrews, an engineer group, explored the various nozzle concepts. Tests that year “proved that small, lightweight movable TVC nozzles are capable of vector angles to 20 degrees, with very fast response times of 20 to 30 milliseconds (that is, a nozzle slewing rate of 600 to 900 deg/sec).”

[..]

Dave Carpenter in Ray Feist’s Engineering Projects Branch was the chief engineer for developing the rocket motor: an 8-inch-diameter solid-propellant

motor with an average thrust of 3,500 pounds for 7 seconds and better than 24,000 pound-seconds total impulse. This burn-versus-time profile (a function of the internal geometry of the motor) permitted the missile to make the turn toward the target in minimal distance before increasing thrust to obtain high velocity until impact.

The motor design later evolved to a 32,000 pound-seconds thrust boost/ sustain rocket motor. Speed and endurance were paramount. “It was all

reaction steering,” said Scott O’Neil, “so when the rocket motor burned out, you better have hit the target, the fuze better have gone off, or else you just

wasted a bullet.”

Flight tests soon followed, using a Thiokol omniaxis gimbal-ring TVC nozzle and a Sparrow hydraulic power supply system. Several flight tests were conducted. In the most impressive one, “a Quickturn flight vehicle demonstrated a 55-g 118-degree angle-of-attack maneuvering capability under a high dynamic-pressure environment.”

Meanwhile, NWC management was itching to get the new technology incorporated in a weapon system— and not just the TVC technology. “The general Agile concept evolved from numerous discussions with fighter pilots on their desires and insights concerning an air-to-air dogfight weapon system,” stated one report. “The basic desire was for an if-I-can-see-him-I-can-hit-him weapon system.”

China Lake had proposed a new version of the Sidewinder called the AIM-9K. The concept, developed by Dr. E. E. “Mickie” Benton, had very similar performance to that envisioned for Agile but was aerodynamically, not thrust-vector, controlled. However, opposition from the Air Force killed further efforts on the program.

In 1969, Justin W. Malloy, director of NAVAIR’s Advanced Weapons Systems Division, proposed a new missile system for the Navy, called Agile,

that would use China Lake’s Quickturn technology as well as seekers with large gimbal angles being developed by Hughes Aircraft Company and Philco-

Ford. The weapon would be given the formal designation AIM (Air InterceptMissile)-95.

Agile gave China Lake an opportunity to propose the incorporation of other new technologies, all at various stages of maturation. In 1970, NWC

described the candidate next-generation air-to-air weapons system:

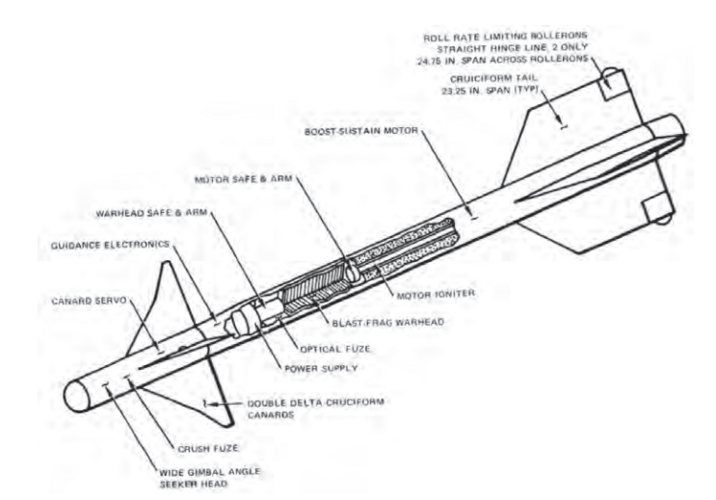

The principal features of the current Agile base-line design are

(1) a head coupled visual target-acquisition system;

(2) passive all-target-aspect guidance, with a large gimbal angle capability;

(3) a relatively clean body airframe incorporating thrust vector control; and

(4) an all-aspect ordnance package with an active optical fuze and an annular blast fragmentation warhead.

Denny Kline served during the Agile years as technical presentations coordinator and later as the Center’s public affairs officer. He recalled:

Here was this extraordinary capability, it skipped a generation, it went from a forward-hemisphere Sidewinder to something that looked, locked, and launched, where you could look over your shoulder and actually do something, which was an incredible Star Wars jump in those days.

The Agile team wasn’t the only group looking to build the next great dogfight missile. The Air Force had its own concept, the AIM-82, which was intended for use with the then-in-development F-15 fighter. The AIM-82, like Agile, was planned as an “all-aspect” missile—that is, it could track the target from any angle, unlike the Sidewinder of the day that had to be aimed from behind the target aircraft to lock on the hot engine exhaust.

The Navy wanted a more generalized missile with both interceptor and self-protection applications, one that could be used on ordnance-toting attack aircraft, such as the A-7, which were generally less maneuverable than the F-15 or the current threat fighters. Captain Tommy Wimberly, Technical Officer at China Lake during Agile development, said:

We briefed and said, “Put this Agile on an attack airplane, and if somebody attacks him, he’ll shoot them down.” The fighter pilots didn’t like that idea. The Air Force guys claimed they didn’t want any 8-inch diameter missile. It was too big, give them something that was smaller and let them fly the airplane to get on the guy’s tail, that’s what they wanted to do.

That issue—whether to rely on the maneuverability of the aircraft or of the missile—was decided in favor of the Navy, and Agile was given the go-ahead.

According to Technical Director Walt LaBerge:

The basis for the decision was in part a belief by DDR&E [Dr. John S. Foster] that the Navy had a better solution and in part a Connolly/Glasser agreement

[Deputy CNO (Air) Vice Admiral Thomas F. Connolly and USAF Deputy Chief of Staff R&D Lieutenant General Otto J. Glasser] that if the Air Force did not contest an Agile assignment to the Navy, the Navy would not contest the Air Force assignment of high energy laser application to air-to- air warfare.

Interservice politics aside, the Agile program faced many technical obstacles. Perfecting a TVC nozzle that could operate precisely and at extremely high slew rates through the full range of the Agile envelope posed both engineering and materials challenges. Agile also required the design and development of a new lightweight 8-inch-diameter annular-blast warhead that would yield aircraft structural kills at the anticipated miss distances. The missile would need a very sophisticated autopilot because, as Phil Arnold (who would later manage the program) pointed out,

“Agile routinely flew through low to zero to negative airspeed regimes while rapidly turning with high angles of attack and with a continually shifting center of gravity.”

Agile’s revolutionary airframe, unlike any seen before in a Navy missile, had no wings at all and only six (later eight) small aft-mounted fins for initial flight stability. As the missile left the launcher, the fins precluded yaw that could lead to impact with the launch aircraft. The TVC was locked down as well so that the missile wouldn’t come back on the shooter’s wingman—which it well could do; the fins kept the missile stable and straight until it was away from the vicinity of the aircraft. Once TVC guidance commenced, the fins had no purpose.

Because of Agile’s extraordinary speed and maneuverability, Center designers wanted to replace the traditional hemispherical seeker dome with a much-lower-drag pyramidal window made of triangular flat segments cemented together—a goal that had eluded engineers since the 1950s.

Agile needed an all-aspect seeker that could track the target tail-on, side‑on, or head-on. It had to be capable of locking on the target when the pilot pointed his head in the direction of the target (rather than, as with Sidewinder, pointing his aircraft at the target). This required a gimbal that could slew the seeker to high off-boresight angles at slew rates of 200 degrees per second. The look-and-lock capability also required a means of slaving the seeker to the pilot’s helmet. That feat was accomplished by computing the helmet’s position using light sensors in the cockpit and light-emitting diodes in the helmet. The concept was called the Visual Target Acquisition System (VTAS).

Initially, four seekers were Agile candidates—three of them IR, one electro-optical (EO). One was a Philco-Ford product using an NWC-built seeker head platform. Another was a Hughes Aircraft Company-built seeker, which underwent major redesign in 1971. A third was a Sidewinder AIM-9D seeker mounted in two extra sets of gimbals to provide the wider gimbal angle required for the Agile envelope. Finally, NWC was developing an EO TV-type seeker—in early testing with a Honeywell Inc. helmet-mounted sight, the EO system demonstrated pointing accuracy of less than 1 degree of error out to 90 degrees off-boresight.

In addition to the four candidate seekers, a two-color sandwich-type IR detector was being developed at China Lake under an Independent Exploratory Development (IED) program that began in early 1971. Operating in two bands would minimize the effects of clutter and decoys and would optimize terminal homing by biasing the missile trajectory away from the target’s engine plume and onto the aircraft itself. China Lake was also developing a sophisticated fuzing system for Agile involving an aft-mounted active optical target-detecting device.

Supporting equipment for the Agile system was in the pipeline as well. For example, Center engineers and human-factors experts were investigating the

incorporation of a voice advisory system in which audio displays by a simulated human voice would alert the aircrew to onboard aircraft problems. The goal was to minimize the time the crewmember spent scanning cockpit displays and maximize the eyes-out-of-the-cockpit time. The technical challenges presented by Agile were significant but not, China Lake felt, insurmountable. Political, personality, and management issues, however, affected the program from the outset.

Late in 1968, Dr. Frosch, Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research and Development (ASN R&D), asked Dr. Joel S. Lawson, Director of Navy

Laboratories (DNL), “whether or not we could assign a major project to the laboratories, and if so, which laboratories would be assigned the projects?”

Lawson told Frosch, “You could assign a major project to China Lake anytime you wanted, but on the other laboratories I didn’t think so.” He went on to explain:

My personal motivation was two-fold. The leading one was that I thought it would do the laboratories good. It would make them a little bit more tolerant

of headquarters if they had to go through this rat race. The other one was the fact that in most of our development programs, the real problems are technical and I felt, and so did Dr. Frosch, that we ought to put some of the more technical programs into the hands of the technical people. We could afford a few goofs in the bookkeeping ends of the game.

Dr. Frosch assigned control of the Agile program directly to China Lake, bypassing NAVAIR. Phil Arnold said:

Agile was part of an experiment by the Assistant Secretary for RDT&E by assigning management authority directly to China Lake . . . I happened to be attending a meeting in NAVAIR on the A-7 FLIR when the announcement was made and saw first-hand the reaction in NAVAIR. As you might expect, the reaction wasn’t positive.

LaBerge later stated:

To my knowledge, no effort to obtain for NWC this anomalous reporting assignment had been undertaken by Rear Admiral Moran [NWC Commander]or Mr. Wilson [Technical Director]. Notwithstanding, the arrangement, when announced, engendered apprehension and resentment on the part of our major customer, NAVAIR.

“Dr. Frosch is the one who tried to force the issue of project management by laboratories,” said John Rexroth, who was, at the time, NAVAIR’s technical assistant for the Aircraft and Weapons Systems Division. It was he who decreed that the Agile missile would be under the management control of the Naval Weapons Center and I thought that was a loser. I worked with Hack Wilson to arrive at a working arrangement between HQ and the Center that I think would have seen the project through. According to Arnold, “They prepared a memorandum of agreement that acknowledged China Lake’s assignment as manager, but gave NAVAIR responsibility for ‘handling the Washington scene.’ ” Justin Malloy, who had been the principle Navy salesman for the Agile concept, was designated the Agile project coordinator in NAVAIR-03.

It was at that point, early 1971, that LaBerge reported to China Lake as Deputy Technical Director, being groomed by Wilson for the Technical Director’s position. Wilson’s first instruction was “figure out how to get Agile done.”

LaBerge lamented the early elimination of the AIM-9K from the competition:

It was estimated to be considerably cheaper in development and probably 15 percent less expensive than the TVC Agile in production. However, [Agile]

had been sold to DDR&E on the basis of the riskier, less well performing, probably more costly TVC design. . . . NWC had viewed the problem of rationalizing a more expensive, less performing Agile as NAVAIR’s problem, not its own. When we got the Dr. Frosch letter [assigning China Lake management responsibility], the problem became ours.

Neither NAVAIR nor NWC was familiar with this type of a working arrangement, and there was a lack of communication and trust between the two organizations. At one point, for example, NAVAIR and Hughes Aircraft supported the use of a rate-stabilized platform seeker in Agile. China Lake

engineers believed that such an approach would cause friction coupling that could jeopardize airframe stability, so they opted instead for a momentum-stabilized rotating-mass optical system similar to Sidewinder’s. LaBerge cited this example in a 1973 background memo on Agile to the newly arrivedNWC Commander, Rear Admiral Paul Pugh. LaBerge called it a “question of arithmetic” and stated, “If we cannot agree on items of fact, we can never agree on questions where the facts are less clear.”

Bob Hillyer, who headed the Fuze Department and would later become NWC Technical Director, blamed the conflicts on Secretary Frosch’s decision to assign program management to the Center.

He forgot to change the rest of the system when he did that. The result was resentment in the Naval Air Systems Command and some other places in the development chain, and authoritarianism on the part of China Lake. That resulted in poor communications between us and the Systems Command, and we didn’t change the fundamental way we did business.

LaBerge had his marching orders from Wilson and quickly took action. At the time, the Agile program was being managed at China Lake by D. P. “Phil”

Ankeney, assisted by Clarence “Zip” Mettenberg in Dr. Highberg’s Systems Development Department. In mid-1971, acting with the concurrence of Wilson and Moran, LaBerge switched department heads, putting Highberg in charge of the Engineering Department and moving Chenault to head the Systems Development Department where the Agile program resided. LaBerge felt that while Highberg was “bright and well intentioned,” he “characteristically did not involve himself with detail and was very slow to action.” Leroy Riggs saw the replacement of Highberg as a personality- and management-style issue. Walt was trying to do Agile as Bill McLean did Sidewinder. . . . that relationship just didn’t work like it did way back in the ’50s with a McLean [Technical Director] to a Newt Ward as the department head . . . . So he pulled Highberg . . . Highberg and Walt didn’t hit it off, so Highberg wasn’t the man.

Next LaBerge hired Frank Cartwright, who was working at Philco-Ford, to return to the Center and manage the Agile Division in Chenault’s department. Cartwright was a renowned engineer and missile designer who had worked on the original Sidewinder and had won the L. T. E. Thompson Award for his management of the Sidewinder 1C program (which developed the AIM-9C and the AIM-9D). He had left the Center in 1961 to go to Philco-Ford, where

he worked on the Sidewinder AIM-9E. After his return to China Lake and assignment to Agile, there were some mumblings of cronyism; Cartwright and LaBerge had long worked together at China Lake, and both had worked for Philco-Ford.

LaBerge’s next step was to start development of a backup version of Agile that did not use TVC but instead maneuvered with traditional aerodynamic control surfaces—forward-mounted cruciform canards and a cruciform tail. Called the aerodynamically controlled vehicle (ACV), it was a 5-inch diameter missile. An NWC report stated that in comparison with the TVC, the ACV missiles were allowed to have less performance while having the imposed design constraints of low risk and cost. However, the ACV missiles were designed to be much superior in performance to existing air-to-air missiles

Despite the ACV program’s low level of effort (LaBerge estimated it would be about 5 percent of the overall Agile program), it drew on some of China Lake’s top talent: Ralph Carter, Art Gross, John Skoog, Steve Benson, Don Quist, Harry Loyal, Doug Turner, Mel McCubbin, and William Holzer. James R. Bowen, who would later head Project 2000, was the development manager.

In mid-1972, a setback occurred for the Agile program when Captain William Mohlenhoff was selected as the point of contact between NWC and NAVAIR. “He had spent a tour at Point Mugu and considered himself competent to make technical decisions,” opined Arnold. The captain had a different idea of how he should exercise his responsibility for the “Washington scene” than did China Lake managers. There was constant friction between Mohlenhoff and the China Lake Agile project management.

“There was nobody in town [Washington] to be the spokesman for the Agile program,” Hillyer said. “There was so much contention between the organizations that instead of its proponent he [Mohlenhoff] became its critic.”

Again, personalities were at play. Arnold said that Cartwright “had little to no tolerance for the disputatious maneuvers of Mohlenhoff who was determined to gain control of the project.” Even LaBerge, who had selected and recruited Cartwright, described him as a “very brittle” person who “does not do well with people he considers dishonest or absolutely incompetent.”

Hillyer, admitting that he was exercising “20-20 hindsight,” contended that the Center should have hired two program managers. One should be a civilian technical manager to run the program; the other should have been a Navy captain that you bought a credit card for, to use on the airlines, so he could go to Washington three times a month and defend the program. Because Washington requires that you do that. So the management scheme was poorly thought out.

At that time, there were numerous versions of Agile in the works, with different combinations of TVC systems, seekers, airframes, and launching systems. The Agile ACV alone came in three different versions—the ACV, the All-Boost ACV, and the Austere ACV.

LaBerge justified this profusion of models:

DDR&E wanted NWC to design a cost effective missile usable by both services. It wanted demonstration of alternatives by DSARC review, and Dr. Foster said that he was relying on the technical integrity of NWC to do what was right to develop the alternatives for cost/performance selection. DDR&E, or at least Dr. Foster, was in no way constrained to the baseline Navy proposal.

But from the outside—and even to some on the inside—there seemed to be too much indecision in the program. “All of these things were going in parallel,” Hillyer said. “Nobody bothered to make their mind up. Nobody bothered to say, ‘Hey, let’s settle this down.’ "

Despite the apparent confusion, real advances were being made. A then-secret 1972 technical film describes the progress on the various components

and technologies. One sequence shows a June 1972 test of a preprogrammed Agile flight-test vehicle. Launched from the ground, it accelerated to 1,525 feet per second, turned to an angle of attack of 110 degrees, and then turned back to its original heading. The film recounts that despite angular accelerations of up to 4,000 degrees per second squared, roll rate and yaw remained under good control. Evaluations not only showed no unfavorable flight characteristics, but proved the Agile airframe to be more stable than predicted.

In January 1972, China Lake physicist Floyd Kinder received a patent for a head-coupled aiming device that he developed for Agile. In 1973, George S. Burdick, head of the Avionics Branch, received the Technical Director Award for a successful demonstration of the Agile seeker, avionics, and visual acquisition system. Burdick’s team had taken a Honeywell-produced VTAS, modified it to meet Agile operational requirements, and installed it in the front and rear cockpits of an F-4J carrying an Agile. Reported the Rocketeer:

The Agile infrared seeker was slaved to the pilot’s or radar observer’s VTAS, positioned on target, and put into the automatic tracking mode. Successful acquisition, lock-on, and tracking operations were achieved by both crew men during operational maneuvers throughout the Agile missile launch envelope.

In January 1973, David S. Potter succeeded Dr. Frosch as ASN R&D. Unlike Frosch, Potter had no stake in the Agile laboratory program management experiment. Six months later, on 30 May, Rear Admiral Pugh assumed command of the Center, and a week later, LaBerge was formally selected as Technical Director. (His previous 23 months of trying to “figure out how to get Agile done,” per Wilson’s instruction, had been as deputy Technical Director).

On the same day he took over his new post, LaBerge briefed Pugh for an up‑and-coming Agile conference. Among his recommendations were that both Mohlenhoff and Cartwright be moved. No time was wasted. On 29 June 1973, the Rocketeer reported that Cartwright “had been selected by Dr. Walter B. LaBerge to serve as a senior technical consultant with Dr. H. A. Wilcox [Howie Wilcox, Technical Consultant to the Technical Director].” Phil Arnold was chosen to replace Cartwright.

“The China Lake Agile office functioned as a division with the program manager as division head,” Arnold said.

This arrangement was similar to that of Sidewinder where it functioned well. My preference would have been a matrix arrangement with a small program office supported by the line organization so that I could be relieved of much of the supervisory responsibility. But Agile was underway and I accepted the job as it was organized.

Captain Mohlenhoff was removed by the NAVAIR Commander and replaced with Mohlenhoff’s assistant, Captain James Quinn. Arnold and Quinn “immediately developed a partnership based on mutual respect,” said Arnold. “The management ambiguities were removed, the program had a competent representative in Washington, and I was relieved of a major inhibitor to focus on other issues.”

Arnold’s leadership team consisted of Lee Gaynor (administration), George Burdick (avionics, including helmet-mounted sight), Irv Witcosky (missile

engineering), Jim Oestrich (system synthesis and simulation), and Don Quist— and later Fay Hoban—(seeker development). As well as a large in-house team, the program had contracts with Hughes for guidance and system integration and Thiokol for propulsion and TVC. “Probably half the base worked on Agile,” Scott O’Neil remembered 40 years later. “It was a huge program.”

Technical progress continued under Arnold’s leadership. One advantage Agile had over earlier missile development programs was a sophisticated simulation capability for use as a design tool and to augment flight testing. “The Agile simulation was a technological marvel that was absolutely necessary to design a vehicle operating in the missile’s flight regime,” said Arnold. As an example, the team had recorded radar tracks of aircraft flying mock combat—the location and velocity vectors of aircraft engaged in simulated dogfights. These tracks were then flown in simulation to test the ability of the propulsion-autopilot of the TVC airframe to handle launches anywhere in the engagement. The most stressful launch conditions, called the “hard shots,” were used in defining the missile design specifications.

1973, the program was using data from 400 actual one-on-one aerial engagements plus 350 “dog fights” conducted in the Ling-Temco-Vought (LTV) manned combat simulator. Monte Carlo simulations, conducted by Arnold Moline, were used to determine the effects of various missile modifications on

the missile’s overall capabilities.

A troubled Navy budget in fiscal year 1973 caused heavy cutbacks, delaying the Agile flight-test program. Major changes were still being made in various subsystems. By the end of the year, the Tech History commented that “the current project tactical Agile was changed significantly from previous designs.”

The pyramidal seeker window was one casualty of the funding cutbacks. When Secretary Potter reviewed the Agile program, Hillyer, as head of the Fuze Department, participated in the review. “He said to the Naval Weapon Center, ‘Folks, what did you do with $70 million?’ ” recalled Hillyer.

And so we spent a day telling him how we spent $70 million, and at the end of the day he said, “Folks, what did you do with $70 million?” So we regrouped spent all night working, and tried again the next day, and he went back to Washington and hired Doc Freeman to change that damn place. That’s not

much of an exaggeration. [Freeman arrived at China Lake in June 1974.] We didn’t answer his question well. The fact is we didn’t spend $70 million on Agile. We spent about $20 million on Agile, and we spent about $50 million on technologies which may have had application to Agile. We should have settled the program down faster.

Burrell Hays also viewed the Potter meeting as the harbinger of Agile’s end:

When Agile was killed, they were still working on five different Agiles. They had three different seeker gimbal limits, and they had two airframes. They had the tail thrust vector control and they had the canard. And, they were working on all five of them simultaneously, and they just didn’t want to stand up to tell Potter that. They hadn’t wasted any money in the sense that they were buying furniture or something, but they were working on five systems instead of one.

LaBerge, who had been trying to fix the Agile program since he arrived in 1971, left the Center suddenly in September 1973, when he accepted the

position of Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Research and Development.

Leroy Riggs stepped into the Technical Director’s position behind him in an acting capacity. In his wake, LaBerge left organizational confusion; during his short tenure as Technical Director, he had instituted the directorate system, essentially adding another layer of management between the Technical Director and the department heads and elevating his three most senior department heads to lead the new directorates. How well the new organizational structure would work was moot. “It was never given an opportunity to work,” said Riggs. “Walt left a few months later. I moved over to the Ad Building [as Acting Technical Director]. I wasn’t about to upset the applecart at that stage of the game.”

As the ’70s progressed, funding became an increasing problem. Arnold said:

The need for funding deficiencies in other programs receiving high priority in OPNAV proved stronger than support for Agile. Each October at the start of the fiscal year, the program received an injection of cash and we ramped up the team. Around December or January, funds were reprogrammed from Agile, our budget was halved, and we had to ramp back down.

“I remember poor Phil Arnold just getting beat to death,” Kline said. “Three months into [the fiscal year] they reclaimed half of their money . . . and then halfway through they came for more and just absolutely sucked the program dry. They cut its head off and let it die.”

Meanwhile, the Air Force was criticizing Agile as too costly and complicated and offered its own candidate - Dillinger referred to it as a “paper missile” - that was called, pointedly, Concept for a Low-Cost Air-to-Air Missile (CLAW).

In their briefings, the Air Force officers argued that the maneuverability issue, which Agile was designed to address, would be resolved with their anticipated new high-performance fighters.

Toward the end of Agile, Arnold cut back on the program, realizing that ACV with the pyramidal dome “wasn’t going to be ready on the Agile schedule, if ever.” So he cancelled the ACV effort. In an interview, Arnold stated that his action

made me pretty unpopular with many smart and competent people at China Lake who had no love for the TVC. I make no apologies for canceling [the ACV] under the circumstances when we were fighting for the life of the program.

Agile did well in its 1974 Defense System Acquisition Review Council (DSARC) review. However, Tony Battista, staff director for the R&D Subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee, applied the program’s coup de grace. As an engineer, Battista had worked at Dahlgren for Chuck Bernard, a former China Laker. On many weapons systems and weapon development issues, Battista was a strong supporter of China Lake’s positions.

According to Ray Miller, Battista had a very influential position, short of having been elected to serve on the committee. He could influence programs very readily because he had the smarts and the access to the people who made the votes and signed the legislation.

Arnold claimed that former Technical Director Tom Amlie convinced Battista that Agile was terribly expensive, wouldn’t work, and wasn’t needed. Tony

killed Agile. I talked to Tony during the period leading up to the Committee markup, and he was friendly enough, he just thought proceeding with the Agile program was a mistake.

Although Battista may have been the immediate agent of Agile’s demise, the cause was a combination of factors. Lack of effective communication and cooperation between China Lake and NAVAIR in the early years of the program was one factor, which may be blamed, in part, on Frosch’s assignment of the program to China Lake management without clearly articulating the relationships and apportionment of functions between the laboratory and its

principal customer.

An attempt to make one missile that would be “all things to all people” was another weakness. A reaction-controlled missile of that size could not

be an effective mid-range or long-range weapon, which gave rise to the ACV variant (which could continue maneuvering after motor burnout). “When you develop a missile to do a specific job, you shouldn’t knock it because it won’t do something else. You want it to do what it’s designed for, and do it well,” said Highberg.

The absence of a single overarching vision of what Agile should be and how it should be developed was a significant problem. LaBerge might have had a vision, but once he left for the Air Force, the program began to drift. Because the direction and goals were ambiguous to NWC, it was impossible for the Center to convince powerful people in the upper reaches of the Navy and DoD that Agile was doable and necessary.

Dr. Dick Kistler, noted warfare analyst and long-time head of the Office of Finance and Management, blamed the program’s failure on NWC’s inability

to sell the program.

I can remember something that Admiral Freeman said which I’ll remember for a long time: that China Lake did a very good job in NAVAIR, but never got

to the “E” Ring [the Admirals’ offices] of the Pentagon. . . . the cancellation of the Agile program seemed incomprehensible here but the admiral’s point was nobody ever sold it to the flag levels. They didn’t even know what it was. It was an aggregation of NAVAIR technology programs which people thought could be put together into something pretty spectacular, but when the money started drying up it disappeared quickly, and the senior military in the Navy just couldn’t care less.

Ernest G. Cozzens, who worked with many major weapon systems, including a stint as project manager for Shrike, argued that the problem with Agile was one of conflicting priorities.

When China Lake originally proposed Agile, it was as a long-term program: The conceptual phase, a year or 2 years, then an advanced development phase of 3 or 4 years, and then a fullscale development of 2 or 3 more years, and at a cost of something like a hundred and some million dollars. Well, the Navy needed the weapon, needed it badly. . .

[China Lake] kept massaging three or four different versions, and the people in NAVAIR, the sponsors in 03, said, “Freeze on one and let’s get into engineering development on it.” And our people said, “No, we’re not through,” and they just kept saying that. And they just kept spending money. And when they got to $82 million and they had not yet even gotten to engineering development, the sponsor says, “They aren’t going to get there. Kill it.”

Cozzens added, “I firmly believe that it was one of the most utterly and completely mismanaged programs the Center ever undertook.”

For the people who had worked on Agile, battered morale was part of the collateral damage from the program’s termination. Phil Bowen explained:

You spend a number of years of your career working on something that doesn’t go anywhere. . . . A lot of blood, sweat, and tears and a lot of long hours and it’s kind of frustrating . . . I think people do it, like myself, because it’s a challenge and we want to do it, we want to prove we can do it. But it wouldbe nice to have it go somewhere.

The morale effects of program termination were part and parcel of the RDT&E world, where far many more programs were started than would ever wind up in the Fleet. Richard Hughes commented on the phenomenon:

A number of people said “Everything I’ve done, everything I’ve designed is laying in a corner, never to be used.” . . . Bright guys and girls left the Station because they wanted to be useful and they couldn’t be useful. . . . In general, nothing they did followed on to anything, and I think this should be expected in any organization. You’re given a job and, oh, this contract runs out, or we didn’t get the money for this, or we proved it wouldn’t work, or whatever. That’s to be expected. What bothered me was that we lost a lot of really, really good engineers that tried to work themselves into a position where could be meaningful and they couldn’t do it. This was not a management problem, this is just part of the system, part of being engineers and scientists.

The millions spent on Agile were not a total loss, because technologies developed for the missile resurfaced in programs as disparate as Sidewinder seekers, helmet-mounted targeting devices, the vertical-seeking ejection seat, and Navy vertical-launch systems.

One example is the trapped-ball nozzle. Agile was originally designed with the same hot-gas trapped-ball (ball-and-socket) nozzle that had been used in

Quickturn. That nozzle had been designed by Thiokol, under contract to the Navy. The first Agile had a 24,000 pound-force second impulse motor, and engineers expressed concern that the Thiokol nozzle, which had 10 critical components, might exhibit overheating in sensitive areas of the nozzle.

When the Agile motor specification was increased to 30K impulse, combustion pressure rose by nearly 20 percent. In anticipation of the potential inadequacy of the 10-component nozzle, China Lake engineer Bill Thielbahr led a design team consisting of Richard Purcell, Richard Thompson, and John Patton, with assistance from Milt Wolfson, to design an entirely new cold trapped-ball nozzle. The team used their experience in materials, heat

transfer, and thermostructural analysis to create a nozzle with only three major components and a 70 percent reduction in parts over the Thiokol design. The team also introduced a new nozzle graphitic material, ATJS (used in atmospherereentry nose cones), to the nozzle-design community. The nozzle performance was demonstrated in a series of nine rocket motor/nozzle tests. The team’s work,resulted in a state-of-the-art TVC nozzle that employed a pneumatic actuator system.

After Agile ended, China Lake retained the documentation for the nozzle. When the Tomahawk Mk 111 TVC booster was being developed, the contractor was having difficulty with gas leaks in a hot trapped-ball nozzle. China Lake transferred the Navy-owned documentation and drawings of the cold trapped-ball nozzle to the contractor, which introduced it successfully into the booster. Subsequently, the same contractor used the China Lake-developed nozzle technology in the Mk 72 booster for the Standard Missile.

Agile, in concept and technology, was well ahead of its time. Even the enemy knew it. Several years after Agile’s cancellation, according to Dillinger, one of the first questions asked by a defecting MiG pilot was “what’s the status of Agile?” They were convinced it had “gone into the black world” of hidden,

more highly classified programs, but were obviously still concerned about it.

Ironically, the Soviets’ belief that Agile was being developed in the black caused them to ramp up efforts on their own high-tech dogfight missile—the

Vympel R-73 Archer, with TVC, helmet-mounted sight, and high off-boresight capability—that began development in 1973 and was fielded in 1982.

Today, U.S. Navy and Air Force pilots rely on the Sidewinder AIM-9X as the principal weapon for short-range air-to-air combat. This $600,000-perround missile employs TVC (jet vane, rather than movable nozzle), a helmet-mounted cueing system, and the ability to lock on targets up to 90 degrees off-boresight. The -9X’s technology and materials are far more advanced than its predecessor missiles, but its technological and conceptual roots go back

40 years, to the AIM-95, the ill-fated Agile.