1. Background

In 1961, the NATO Basic Military Requirement (NBMR) #3 project was initiated as an attempt to find an alliance-wide solution to a common requirement for a VTOL light strike reconnaissance aircraft for the NATO Air Forces. In January 1962, NBMR 3 ended in an impasse after which each competing nation pursued its national project(s) on its own.

[1] The French continued with their VTOL Mirage II

[2], the British with their VTOL Hawker P.1127 (which eventually evolved into the Hawker Siddeley AV-8A Harrier and later the McDonnell Douglas AV-8B Harrier), and finally the U.S. and FRG with their respective efforts which will be covered shortly.

2. Organization

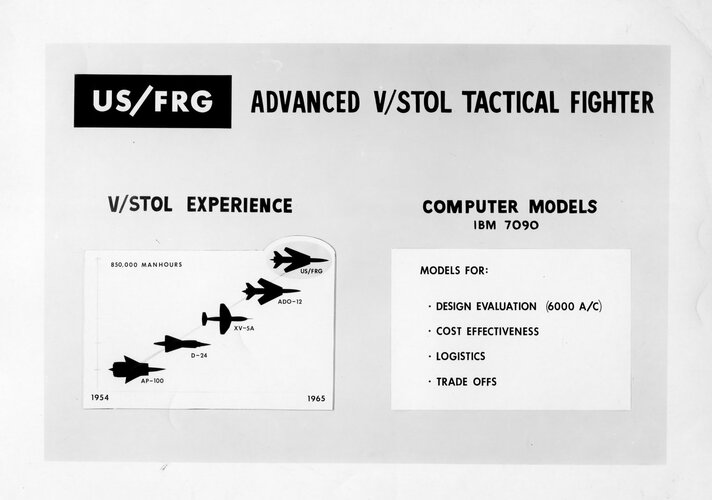

Unlike the purely unilateral approach of France and Britain, the U.S. and the FRG decided to establish a working group to study the feasibility of combining their separate V/STOL fighter aircraft projects into one joint development project. This was part of the wider effort to launch joint development projects that would pick up where the existing joint production projects were about to leave off. (The American-German MBT-70 was the other major transatlantic project emendating from this effort. All the successful ones, how ever, were to exclude the U.S.) The study group recommended that the program be undertaken jointly and consist of three distinct phases: Conceptual; Prototype Definition; and Acquisition. At the conclusion of each phase a new joint agreement would be signed prior to proceeding to the next phase. The first phase commenced subsequent to MOD'S dated August 1, 1963 and February 5, 1965. In addition, there was an International Agreement on Cooperation in R&D for V/STOL aircraft signed on November 14, 1964.

Within the NATO Armament Committee (replaced by CNAD in 1966), the U.S. and FRG's Senior National Representative (SNR) coordinated policy for the project. Under them came a joint study group, and later, one for joint evaluation.

Development costs were to be shared on a 50 - 50 basis, but work sharing was expected to be somewhere around a 60 - 40 ratio in consideration of the U.S.- FRG troop offset arrangements. The two nations agreed that English would be the official language for the program and the Anglo-Saxon system of weights

[3] and measurements would be used.

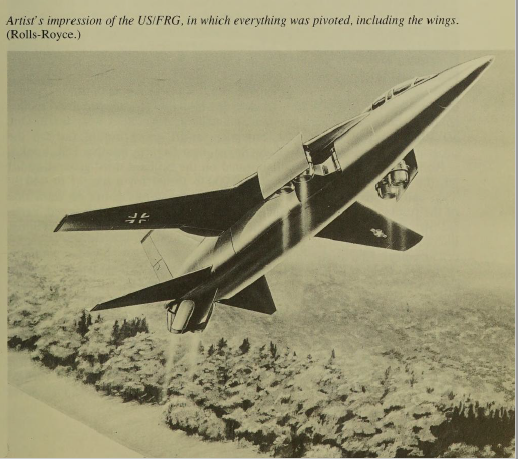

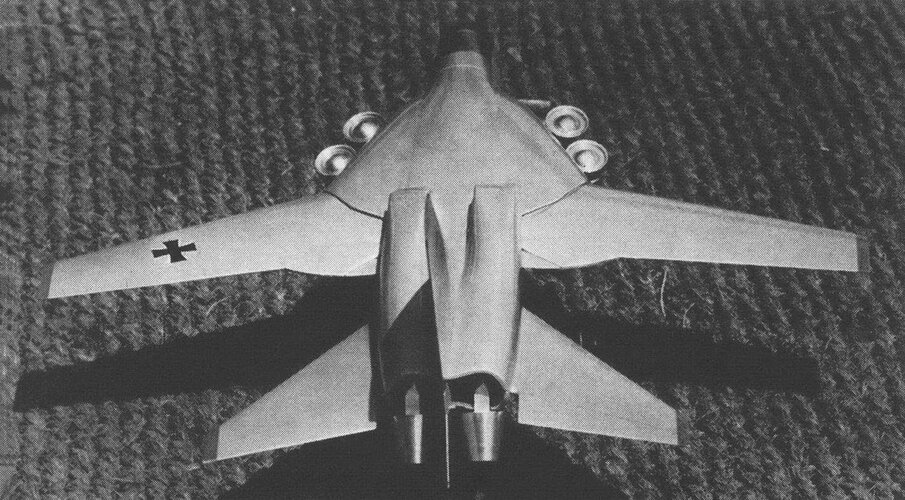

The ultimate weapon system was to be a V/STOL tactical fighter aircraft with the following capabilities:

- All-weather, low-level, high-speed penetration, for delivery of either nuclear or non-nuclear ordnance at medium ranges.

- Air-to-ground strikes in support of ground combat operations at short range.

- All-weather, low-level, high-speed penetration reconnaissance and/or strike reconnaissance at medium to long ranges.

- Air-to-air combat of a self-defensive nature.[4]

The engines for the fighter were covered in an independent parallel program involving the joint funding by the U.K. and the U.S. of the Pegasus engine (later to power the Harrier). The RolIs-Royce / Bristol Siddeley Pegasus was a vectored-thrust vertical-lift engine and had represented a breakthrough in turbojet engine design.

The Pegasus engine dates back to 1957 when the U.S., through its Mutual Weapons Development Program (MWDP), provided funding to Britain's Bristol Siddeley corporation for its development. One estimate put the U.S. contribution through 1965 at $26 million or 56% of the total development cost. On October 20, 1965, the U.S. and U.K. signed an MOU for the development of a 5 direct lift engine for V/STOL aircraft.

[5] The U.S. contracted with the Allison Division of General Motors and the U.K. contracted with Rolls-Royce. A joint Project Board and an Industrial Program Manager for the vertical lift engine provided support to the U.S./FRG V/STOL project.

[6]

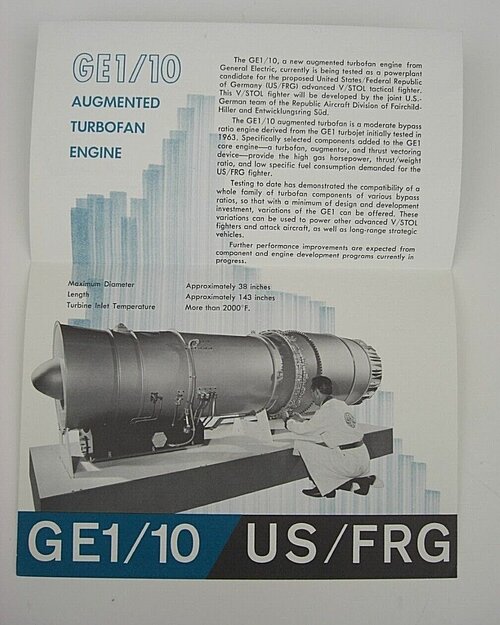

In addition, two other U.S. contractors, Pratt & Whitney and General Electric, were both engaged in a contract definition competition for a lift-cruise engine that would be applicable either for the AVS project or the USAF's FX and the USN's VFAX projects

.[7]

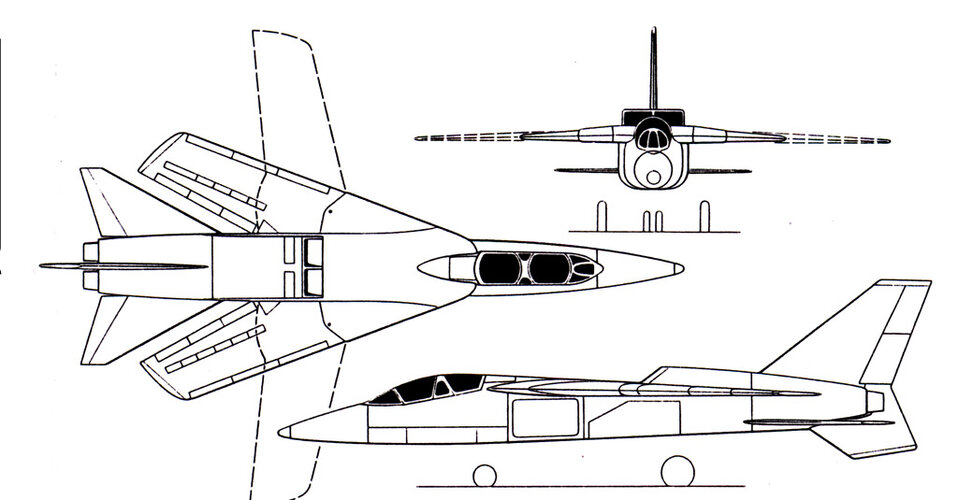

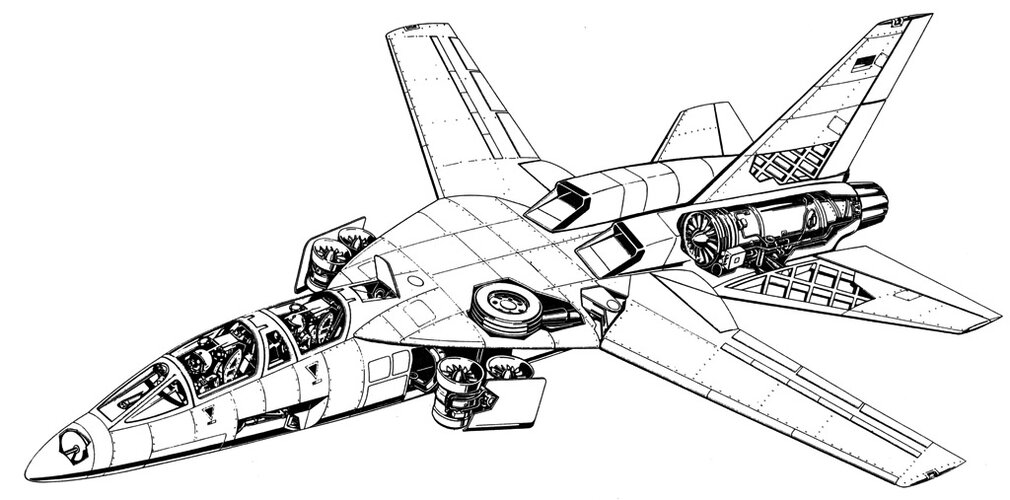

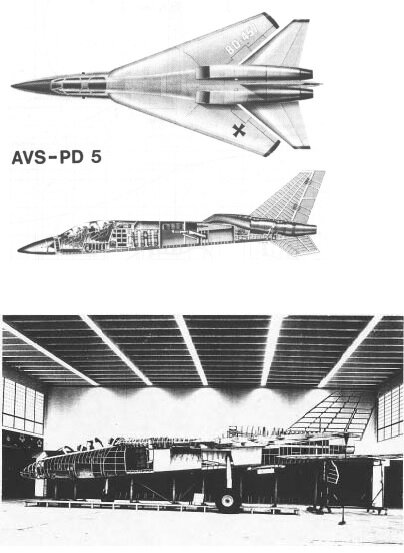

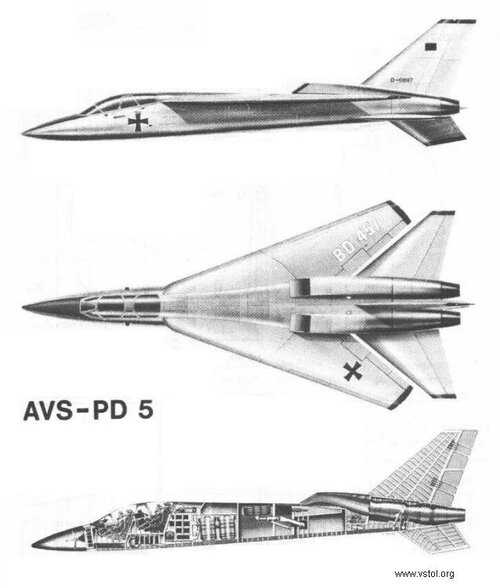

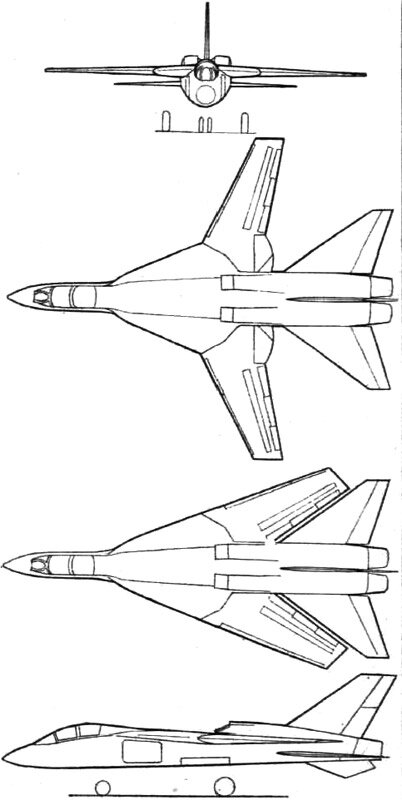

3. Design Study Program

There were two German contractors, and eventually two U.S. contractors, submitting proposals during the Design Study phase. Each country was to hold its own source selection with the understanding that its selectee must be able to work with any one of the contractors from the other country

. [8] Subsequently, the joint evaluation group was to select the best design characteristics from any or all proposals submitted and come up with a single configuration.

Whereas VTOL activity died down in the U.S. after the NBMR 3 impasse in January 1962, the German aerospace industry (along with the British and French) had continued its.national programs.

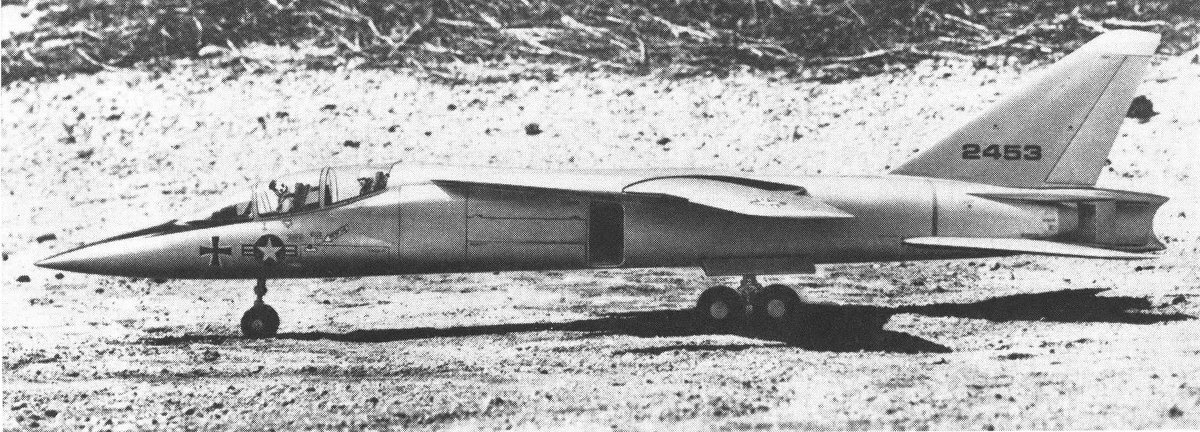

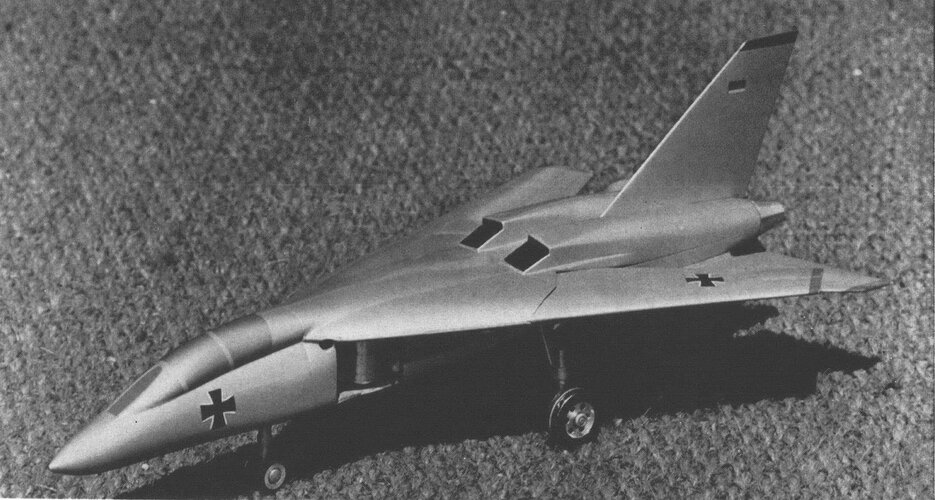

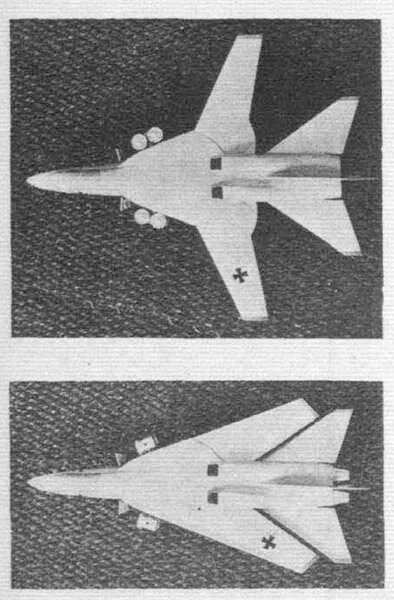

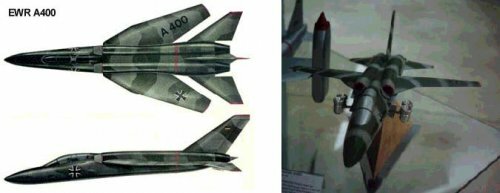

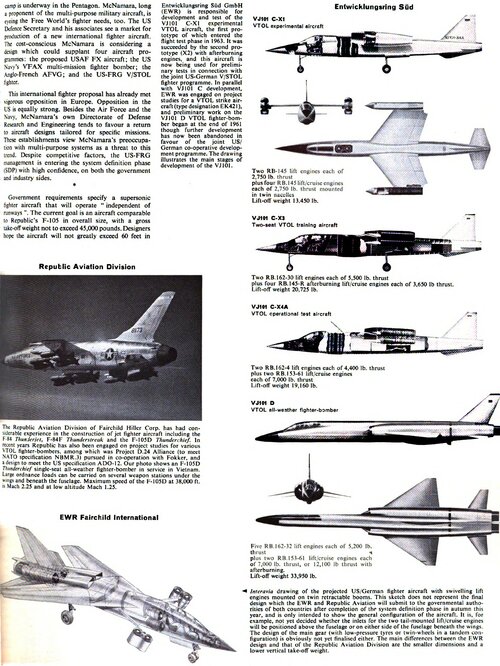

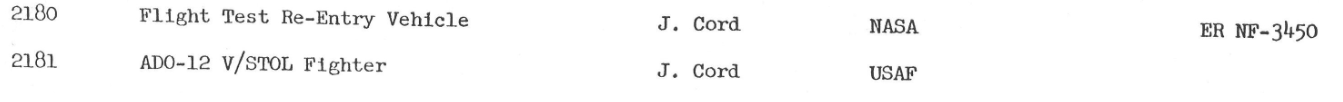

The two firms selected by the German Defense Procurement Agency, The Bundesamt fuer Wehrtechnik und Beschaffung (BWB), were VFW GmbH and Entwicklungring Sud (EWR) GmbH. Both EWR and VFW were brought under contract in late 1963.

Messerschmitt had previously developed and flown its VTOL VJ-101 prototype, and VFW its VAK-91 prototype. EWR, a jointly owned subsidiary of Messerschmitt, Boelkow and Siebelwerke took over the VJ-101 from Messerschmitt in 1964

[9]

EWR had a staff of about 250 working on the AVS alone, with an additional but smaller staff supporting F-104G reliability and maintainability efforts. Most of the AVS staff was to later reappear in the MRCA Tornado project, providing the core personnel. Representative of this, EWR's AVS Program Manager was Gero Madelung, later the MRCA's third Program Manager, and AVS Deputy Program Manager was Helmut Langfelder, the MRCA's second Program Manager.

[10]

In the fall of 1964, Boeing was given the first of three subcontracts by EWR to provide technical support. Manning levels for the Boeing team in Munich working with EWR started out at seven people in October 1964, and increased to 14 the following month with the signing of the intergovernmental MOU. In January 1965 Boeing received its second subcontract and its Munich detachment stabilized at approximately 40 people between May 1965 and January 1967. EWR, for its part, had a small team averaging around a half dozen men in Seattle during this period.

[11]

The rationale behind the teaming up of the two firms was relatively simple. Both firms could see the NATO-wide VTOL interest in fighters. On EWR's side, Boeing, as one of the world's leaders in aerospace and as one third owner of Boelkow, was a logical choice for a partner for its first post-war fighter design effort. Boeing for its part, was interested in getting back into the fighter business (the last Boeing fighter to enter series production dated from the 1930's).

[12]

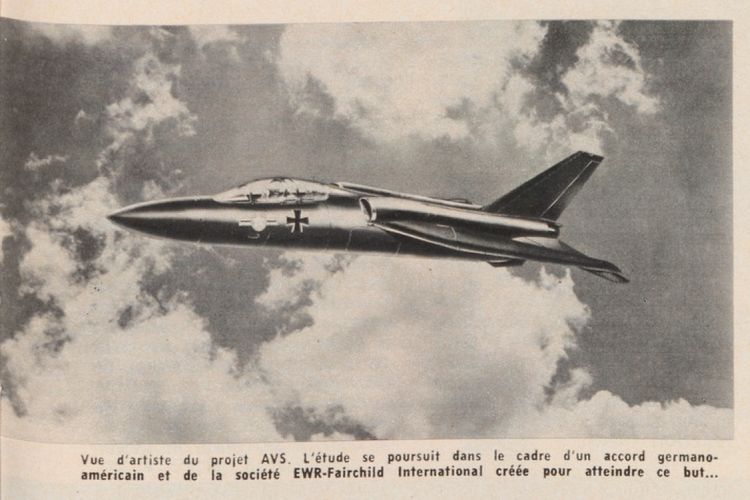

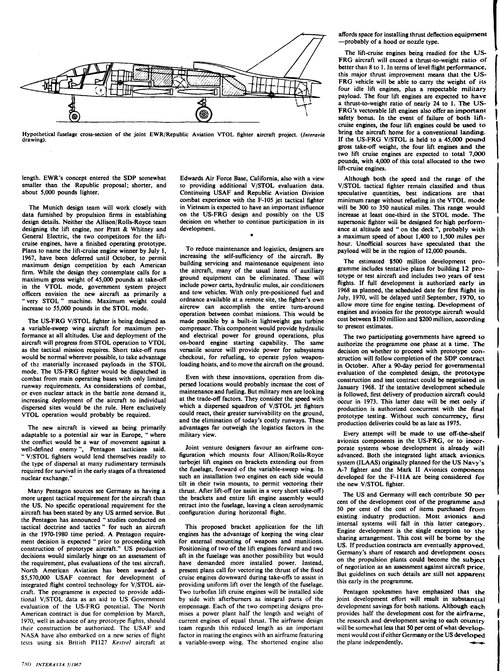

As the U.S. side of the project came on stream later than that of the FRG, Republic-Fairchild entered the picture in early 1966. Reflecting a similar but looser teaming relationship between the other two firms, Republic-Fairchild sent a team to VFW (Bremen) in early 1966, be it a smaller one than the Boeing team. VFW also sent a small group over to Republic-Fairchild in the U.S. The tight EWR-Boeing collaboration not surprisingly led to considerable cross fertilization, so that in the end, among the four designs presented in late 1966, the EWR and Boeing designs were virtually identical. The U.S.A.F. took exception to this and at the last minute Boeing was required to revise its proposed design. In the end the EWR design was judged by the two Air Forces

[13] to have been the best of the four.

Although this would eventually present the U.S.A.F. with a dilemma, it was cognizant of the close EWR-Boeing relationship throughout, and even encouraged it. Moreover, the USAF SPO requested both U.S. contractors submit, as an element in their proposals, their teaming arrangements. Republic-Fairchild had taken another tact than that of Boeing's, however. Feeling this represented an endorsement of collusion that threatened to bias the competition, they let it be known they would protest on these grounds if the Boeing design was selected. The Source Selection Evaluation Board had trouble dealing with this rather ticklish issue, and opted not to score this part of the proposal, only noting it. Thus Boeing's successful teaming relationship served, in the

[14] end, as a penalty in yet a second way.

The January 1967 parallel source selections following a joint evaluation by the SPO, led to the award of a $6 million contract by the USAF's ASD to Republic- Fairchild and a comparable award to EWR by BWB for the prototype definition phase. By the month following source selection Boeing scaled down its 40-man team at EWR to seven (which continued to support EWR under a third subcontract), while Republic-Fairchild built up its team at EWR to about 70 to 80 men. As a residual of the tight EWR-Boeing relationship, and the Boeing content in the EWR design, the Boeing team in Munich gradually tapered off during 1967 and into early 1968.

[15]

An agreement had been reached early in this phase allowing each country's representative to have unlimited access to all data generated and submitted to the joint study group.

[16] One of the important deficiencies of the project, which appeared during this phase and continued through to cancellation, was to be the lack of a definition

[17] of the system's operational role.

4. Prototype Definition Phase

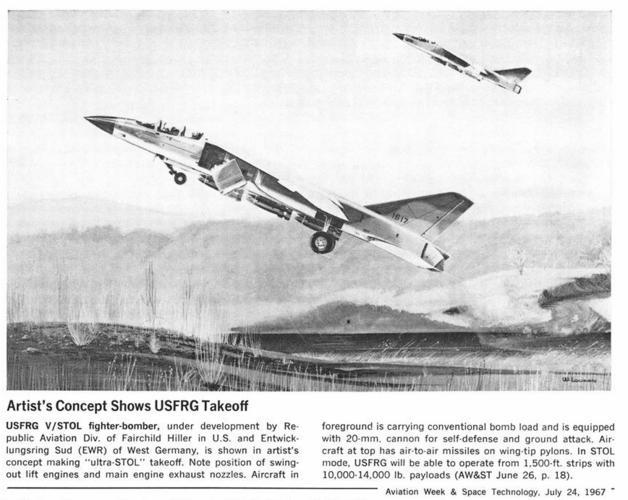

On April 12, 1967, the individual national efforts, i.e., the German Study Group and the U.S. project personnel, were combined into a single group known as the U.S./FRG V/STOL Tactical Fighter SPO (and the SNR established a project steering committee). Also in April 1967, the German and American contractors

[18] set up EFJ, headquartered in Munich.

During the Prototype Definition phase EWR and Republic-Fairchild jointly developed a detailed plan for contractor production of the prototype aircraft. This plan called for the assembly of seven prototypes in the U.S. and five in the FRG. The estimated cost of this stage was $500 million.

By June, 1967, interest within the two customer governments seemed to be drifting toward a more limited prototype program, rather than committment to a production program. When the evaluation report of the Prototype Definition phase study was completed in late 1967, it indicated that the contractor had satisfactorily accomplished the objective of defining general system design and performance specification. This was qualified, however, by the statement, "the contractor's Definition phase final report revealed some omissions and treatments in less depth than was expected." Since this was the contractor's initial proposal, it was generally felt however, that these deficiences could have been resolved through negotiation between the SPO and the contractor so as to insure the quality needed by the Acquisition Phase contract. Instead, in January 1968, the Steering Committee decided to cancel the program for an assortment of reasons to be discussed in Section 5 of this sub-chapter.

The principal technical deficiencies of the proposal involved a need for additional analysis in the engineering and technical spheres concerning reliability and maintainability, plus a need to further refine cost estimates. The first two problems of reliability and maintainability were particularly significant for such a V/STOL aircraft since it would be operating from dispersed and unprepared sites, and thus requiring a high degree of self-sufficiency.

Another problem concerning cost estimation involved an apparent unwillingness of the contractor to share cost risk and its use of an inappropriate learning curve. These, however, were not the primary reasons for the project's demise.

[19]

5. Cancellation and the Issues

The SPO was in the process of validating the final reports of the Prototype Definition phase submitted by the contractor EWR, when the U.S./FRG Steering Committee decided on January 29, 1968 not to enter the Prototype Acquisition phase. The reasons given by the U.S. for the project's termination were that increasing monetary constraints created by the operational demands of the Vietnam War were limiting R & D projects, and that the USAF had not established an operational requirement for the aircraft. Consequently, the SPO and the program were disbanded by June, 1968.

The lack of a firm USAF operational requirement had haunted the project from the beginning. The Luftwaffe's interest in a VTOL fighter had been stronger than the USAF's, but was conditional on having a NATO partner. The Luftwaffe had no plans to go it alone. Boeing, and later Republic-FairchiId, attempted to integrate the technology into a specific design, and persuade the USAF that such an aircraft was needed. The USAF kept edging up to the line, producing draft Required Operational Capability (ROC) documents, but wouldn't cross over.

[20]

a. On the Plus Side

One objective that was stated as applying to the program generally, but was not explicitly stated as such in any one of the phases, was the goal of advancing the technology of both nations. The U.S. advanced its technology through the investigation of V/STOL concepts as applied to fighter aircraft, while the FRG received valuable knowledge in jet engine technology.

[21] EWR went on to use the design staff and knowledge to jointly design, develop and produce the Tornado multi-role combat aircraft (MRCA) with the U.K. and Italy.

Another accomplishment of the program was its promotion of the on-going exchange of V/STOL technical data between the two countries. When the program terminated, the two countries agreed to a semi-annual conference where researchers from the AFSC V/STOL Technology Branch would exchange data with their counterparts in the Luftwaffe.

[22]

The 1976 GRC study cited the AVS project as an example of the valuable intermediary role that SPO can play in improving communications and facilitating the work of industrial firms in a collaborative development project. The SPO was located at Wright Patterson AFB, Dayton, Ohio, and incorporated about 20 German engineers. One of the bright spots of this ill-fated program was the smooth functioning of government and industry people at the technical level.

[23]

Yet another plus for the project according to Baas, was German government and industry having obtained valuable insight from its U.S. partners (first Boeing from 1964-1967 and then Republic-Fairchild from 1967-1968) into the systems approach to the design and development of complex weapon systems. The U.S.Government and its aviation industry had developed sophisticated management and production practices that had been proven in past programs. The German participants were therefore introduced to advanced management concepts, and the knowledge acquired in the U.S. in systems development.

[24]

In the words of one Boeing engineer assigned to the EWR technical assistance team, "German government and German industry got out of it 80% of what they wanted in both technology transfer and systems management know-how".

[25]

Three additional justifications for pursuing the project were that: it complemented the U.S./U.K. Pegasus engine effort; it would probably have had some net Balance of Payments (BOP) benefits for the U.S.; and it would contribute to the increased standardization of the two countries' equipment. But since the project never advanced beyond the paper studies phase, these obviously came to naught

. [26]

b. Reasons for Terminating

One factor contributing to the demise of the U.S./FRG V/STOL fighter program was "not invented here" (NIH) syndrome. As a means of minimizing competition head-on with the highly developed U.S. industrial base, European industries began actively seeking out in the early '60's those special fields wherein the U.S. had expressed little interest. One of these in which a large amount of development work had been accomplished by the Europeans was VTOL aircraft.

[27]

Considerable criticism was directed at the U.S. for not taking advantage of this know-how through direct purchase or license agreements, but rather learning what Europe had already learned. In any case, with the decision in the early '70's to directly purchase the AV-8A Harrier from Britain to provide the U.S. Marines with a VTOL fighter, plus obtain a complete data package for further development of that system (the AV-8B), as well as produce the Franco-German Roland II missile system under license, the U.S. attitude belatedly began to show signs of change on this point. One underlying reason for the program's termination was reportedly the reluctance on the part of the Air Force, with some backing in DDR&E, to place the development of a front-line fighter in the hands of another country. This concern involved both considerations of security and the difficulties anticipated in international R&D.

[28] Just compare this project, or the MBT-70for that matter, with the successful NATO Seasparrow project, where the DoO was willing to risk joint engineering development and production of an improved version of the USN (Basic) Seasparrow system (with only about 10% European content).

An additional factor, which is probably the most important single factor contributing to the program's demise, was the DoD's budget scrimping on all non-Vietnam-oriented programs. This resulted in the DoD's curtailing of several high-risk research projects, including the V/STOL fighter and an Army competition for a high-speed helicopter.

[29] Although less important, the FRG, as well, was experiencing financial problems at the time. The Ministry of Defense was feeling this strain and was reducing its research expenses in favor of operating expenses and the direct purchase of U.S. military equipment (e.g., the F-4 Phantom covered in Chapter 11). Finally, there are the implications of the lack of an operational mission, a point already covered under the Design Study phase. Neither during the Design phase nor the Prototype Definition phase was there any evidence that the USAF had defined an operational mission for a V/STOL fighter aircraft, a condition, which persists to this day. This lack of definition contributed to the complexity of the aircraft which the industry-government team was attempting to design. The engineers had to design an aircraft that would possibly be used in interdiction, close air support, and reconnaissance roles. The concept of dispersal with minimal support further increased the need for a complex aircraft.

But this complexity in turn resulted in decreased reliability and maintainability which either increases the quantity required, or increases theneed for logistic support. These alternatives proved to be both expensive and working at cross-purposes with the original concept of concealment and mobility

[30]

6. Summary

According to the Baas study the program cannot be considered a complete failure. Part of its objective was to advance technology and promote the exchange of data, both of which were accomplished, though the desirability of the latter point was somewhat debatable as far as the Germans were concerned. The German government, along with Messerschmitt and Boelkow, also obtained valuable insight into the systems approach to design and development of complex weapon systems. This was transferred directly to the subsequent Tornado MRCA effort.

The difficulties of the program, which in any event never had more than luke-warm backing in the U.S.

[31] can be classified as financial and technical. Probably the most important single factor contributing to the program's early demise was the U.S. defense budget being stretched in order to support the war\in Vietnam, causing R&D efforts to be curtailed. The cost of the proposed program was highly uncertain with the government and industry differing as to the amount and the sharing of risk. The FRG was also forced to reduce R&D. The technical difficulties stemmed from the USAF's inability to define an operational mission for a V/STOL fighter. The anticipated problems in reliability and maintainability were a result of the complexity of the aircraft design. And finally, there was strong feeling in the U.S. and the DOD towards procuring only weapon systems of U.S. origin.

[33]

And as one final point, the teaming of firms from different nations prior to a common source selection surfaced a critical issue for joint design and development projects where the U.S. is one of the participants. The issue emanates from the differing U.S. and European competition policies (generally speaking, structural versus behavioral) and especially as they apply to defense procurement. The USAF's dilemma and the reversal of its position on the Boeing- EWR (i.e., Messerschmitt-Boelkow) teaming relationship in the final days of the competition provides yet another example of the difficulty of finding a good fit when the U.S. is a partner in a joint design and development project.

7. Sequel

As the FRG was depending on the AVS program (at least originally) to provide its next generation fighter, a feasible design and partnership was required to replace it. Fortunately for the Germans, the British as well had found themselves in a similar situation with half a fighter program, after the French had dropped out of the two year old Anglo-French Variable Geometry (AFVG) aircraft project in mid-1967. Discussions began in May 1968 between the British and German governments (joined by several others) in Brussels within a NATO working group and led to the signing of an MOD later in the year. The new aircraft was to be Multi-Role Combat Aircraft (MRCA) Tornado (See Chapter 8).

Meanwhile the intra-German and interallied partnerships established during the AVS project were to have a decisive long-term impact, in parallel with the launching of the MRCA project. Consolidation of the German aerospace industry had proceeded with the owners of joint EWR subsidiary finally making the plunge. Messerschmitt, Boelkow and Siebelwerke merged in mid-1968 to form Messerschmitt-Boelkow which, now compliant with the German government's demands for concentration of the aerospace industry, was designated by the government to be the German partner firm in the new joint project, the MRCA Tornado. Furthermore, MB's selection to be the German industrial participant was the result of its having won the prior AVS competition. This in turn was the fruit of the intense collaborative relationship built up over the 1964 to 1967 period with Boeing. The year following the MB merger and the launching of the MRCA Tornado project, 1969, the consolidation efforts took another step further with MB-Hamburger Flugzeugbau (owned by the Blohm family) merger to form MBB.

The other AVS partner, the U.S. Government, followed its own course which indirectly led to another joint VTOL fighter project involving the U.S. and the U.K. during the 1970's. Though a VTOL mission never did surface in the USAF, another service, the U.S. Marine Corps, did have a requirement for a VTOL ground support fighter. In 1971 the USMC bought into the British AV-8A Harrier program with a purchase of 110 aircraft and the technical data package. The Pegasus engine utilized by the Harrier was the fruit of an earlier joint U.S.-U.K. effort interrelated with the AVS. After a series of joint and unilateral improvement programs the two governments went forward in 1981 with the 400 aircraft AV-8B Harrier program (See Chapter 9).

Notes

[1] See Chapter 5 for a description of the ill-fated NBMR procedures (1959- 66) and a short history of NBMR 3 in particular.

[2] The Mirage II flying test bed/prototype underwent a short history of considerable hover and flight testing prior to its crash in the summer of 1962. Deficiencies centered on the flight control system and engine instability. Following the crash, Dassault built a new and larger VTOL aircraft, the Balzac, which though externally similar to the Mirage II was a completely different aircraft. Back in 1959, Dassault and Boeing had signed a technical exchange agreement on VTOL aircraft. Boeing had been doing considerable wind-tunnel testing on a design similar to Dassault's Mirage II. Over the following three years Boeing provided Dassault with wind-tunnel test data in exchange for Dassault's flight test data. The agreement proved to be a very beneficial one from both firms' viewpoints. (Source: Tom Lollar, one of several Boeing engineers involved in the effort.)

[3] Capt. Melvin T. Baas, United States Involvement in Co-development: An Analysis of the US/FRG V/STOL Fighter Aircraft and NATO Sea Sparrow Project, a thesis presented to the Air Force Institute of Technology, August, 1971, pp. 26 and 32.

[4] Ibid.

[5] This issue resurfaced in the fall of 1971, during negotiations between the U.S. and U.K. Governments, and Rolls-Royce (having since absorbed Bristol Siddeley) and Pratt & Whitney and General Electric, over the licensed production of the Pegasus 11 (powering the AV-8A Harrier) and a joint license-development program based on the Pegasus 11. The U.S. Government claimed it retained limited proprietary patent rights to the Pegasus engine from the previous MWDP funding. This issue took several years of negotiations at the governmental level to resolve. (Aviation Week and Space Technology, October 8, 1971, p. 16).

[6] Baas, op. cit., pp. 17-18.

[7] "Cancellation of U.S./German V/STOL Fighter Won't Hinder Important Lift/Cruise Engine," Aerospace Technology, Feb. 12, 1968, p. 12.

[8] Baas, op. cit., p. 23.

[9] Interviews with Robert E. Kesterson, U.S. Roland Marketing Manager, Boeing Aerospace Company., February 1982, formerly of the Boeing AVS engineering staff in Munich from October 1964 to January 1968.

[10] The first MRCA Program Manager was Ludwig Boelkow himself.

[11] Kesterson, op. cit.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Baas, op. cit., p. 23.

[16] Ibid., p. 24.

[17] Ibid., p. 28.

[18] Ibid., p. 17.

[19] Ibid., pp. 28-30.

[20] Kesterson, op. cit.

[21] Baas, op. cit.

[22] This point was evidently somewhat debatable. A contrary view was expressed in the FRG a year after the project had ended— a view which also is a good example of the sensitivity of the issue of data exchange. At that time the next generation of fighters was expected to be V/STOL. This was a field in which the FRG had done considerable research and operational testing. In the words of the one official, "We exchange all our V/STOL information with the U.S. We are very much afraid that eventually we will be buying back our own know-how." "U.S. Pressure Against European Fighter Seen", Aviation Week & Space Technology, January 13, 1969, p. 20.

[23] GRC op. cit., p. 257.

[24] Baas, op. cit., p. 28.

[25] Kesterson, op. cit.

[26] Ibid., pp. 27-8 and 30-1.

[27] Another such area was all-weather, short-range, low altitude air defense systems, i.e., Roland, Crotale, and Rapier.

[28] Cancellation", op. cit., p. 12.

[29] Aviation Week & Space Technology, Feb. 12, 1968, p. 27.

[30] Baas, op. cit., pp. 33-4.

[31] Aviation Week and Space Technology, January 29, 1968, p. 28.

[32] Baas, op. cit., p. 35.

[33] Ibid.