Senior Prom

Advanced Tactical Cruise Missile (ATCM)

In early 1976, the Sk Wks began to look at the application of stealth to different vehicles and missions. One of the most attractive program was a stealthy Air Launch Cruise Missile (ALCM). We looked at small or short range and ALCM sized or long range cruise missiles. In Aug 76 Willis Hawkins was attending an AF Scientific Advisory Board meeting in San Diego, and one of their main topics was the improvement of the standard ALCM. That same week I had briefed Maj. Gen. Leaf of TAC on Have Blue who also discussed ALCM. Maj Gen Tom Stafford, who at that time was head of Edwards Flight Test Center, and would later become DCS for R+D at USAF Hdqts in Pentagon also thought we should look at stealthy ALCM. So we aggressively looked at various designs, all using the same faceted approach we used on Have Blue. We narrowed our design to one that would give about 2000 miles of range and weigh about 2500 lbs. In Nov. 1976, Tony Batista, staff director of the House Armed Services Committee visit the Sk. Wks for a HB briefing. He asked if we had looked at a cruise missile and I showed him our Stealthy ALCM.

He asked if I had shown this to National Security Council. I answered negative. I had been cautioned by Lt. Gen Al Slay, the DCS for R+D at USAF Hqts., not to do anything to jeopardize the B-1A program. I did not tell Batista this. Batista suggested I definitely talk to Gen Dave Jones, USAF Ch. Of Staff, and Lt Gen Al Slay about our stealthy ALCM.

In the mean time at the direction of Dr. Bill Perry and Gen Slay, the AF set up a group in the Air Staff at the Pentagon to handle all the Low Observable work under the program security umbrella called Senior High. The group would report to Maj. Gen Bobby Bond. This group of “tigers” consisted of Col. Dave Williams, Maj. Ken Staten, Maj. Joe Ralston, Maj. Jerry Baber, and Maj. Bob Swarts. Every one of them an aggressive “do-er”.

In late 1976, I called Dan Tellep, who at the time was the head of LMSC’s Aquila program for which they had a production contract. Aquila was an Army short range ground launched drone that would do low altitude reconnaissance and return to be retrieved in a net. Tellep (he is the current Charman + CEO of Lockheed) came down to Sk Wks and in a one day mtg. with Passon and myself laid out a cruise missile plan. The plan proposed a 30 month test program using 8 test vehicles for an estimated cost of $50 M in FY77 dollars, excluding engines, passive guidance systems and carrier aircraft. Gen Bond came to visit the Sk Wks on 14 Dec. 76 for a HB update and I showed him stealthy ALCM. He got very excited. In mean time I assigned Milt Jantzen to worth LMSC on a more detailed plan for an unsolicited proposal and presentation and have Passon cost. On 19 Dec. 76 I got an urgent call from Gen Bond to come to Wash DC with our cruise missile plan. I arrived in Wash on 21 Dec and briefed Slay and Bond on our ATCM, which I called Sr. High I. They were both impressed. Once again Jantzen + I met with Tellep and his troops to update our plan and quote. In Feb. Gen Bond + Col Tom Jones we given our updated material. Bond said he wanted to give us a study contract by May 15, 1977, but to keep my quote under $2 M so he wouldn’t have to go to Congress to get $’s. So on June 22, 1977 I received a study contract for Phase I for an ATCM (Senior High I) for $1.9 M. Phase I was to refine the requirements and vehicle configurations, conduct wind tunnel and RCS tests and prepare a plan to build a few prototypes. Phase II would build and test the prototypes. Phase III to be the Full scale development and finally full scale production. The ATCM would be air launched from either a B-52 or a B-1A bomber. The B-1A was later deleted as the program was cancelled in Aug 1977. I believe our ATCM influenced that decision. It coincided with a briefing I made to Dr. Bill Perry, and a group of National Security Advisors for Brezinski’s staff. Perry was impressed by our independent Hughes Co. Threat analysis showing the high survivability of our ATCM. He asked that we vary the altitude to see its sensitivity to vulnerability, and requested we then present it to him and his staff.

On 15th Oct. ’77 we got the go ahead for Phase II for the ATCM (Senior High I). It was not till Oct 1978 when program was transferred from Wright Field to the Low Observable Special Project Office (SPO) did the name change to Senior Prom. This coincided with Lt. Gen Slay’s promotion + transfer to command Air Force Sys. Command as a 4 star. He took the program + transferred it to Wright Field and set up to Wright Field Low Observable SPO to lead up all future stealth programs.

Phase II was tasked to design, develop and test a prototype configuration of an ATCM. A total of nine vehicle systems were to be produced, seven flyable ad two for ground test. A flight test program was set up with a goal of ten successive successful flights as the criteria. Since we were only building seven flyable system, it was necessary to build a parachute recovery system, so that the vehicle could be reused. (Some of the vehicle were reused 3 times during program) The overall objective of this phase was to ascertain the readiness of the ATCM for production (Phase III).

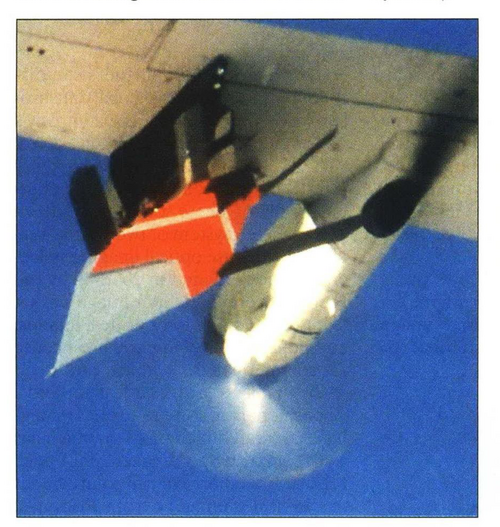

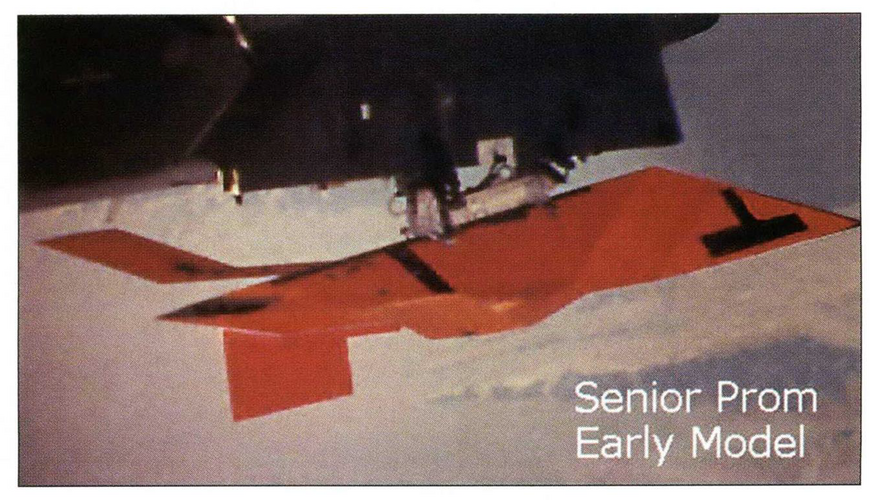

At the end of Phase One we came up with a vehicle design that look like an arrowhead that had a launch weight of 2420 lbs, including 1000 lbs of fuel, and had a range of 2000 miles at M=0.7. The vehicle fuselage looked like our Hopeless Diamond calibration except it had folding swept wing that folded underneath the fuselage during “carry out” and would unfold after launch. The vertical surface for rudder control were located at the wing tips, canted outboard 30⁰ from the vertical. The vehicle was about 18 feet long and 2 feet tall, and a wing span with wing unfolded of about 12 feet. The fuselage had a forward facet which held a trapezoidal gridded inlet to feed air to the turfan engine followed by a two dimensional vaned exit at the trailing edge. The engine was modified Williams F-107 turfan. The entire periphery of the leading edge of the vehicle utilized a fiberglass coated wedged honey comb step loaded with ferrites to a depth of 4 inches. The latter for low frequency absorption. The entire surface was then coated with a .0020 to .0040 in thick high frequency absorber. We froze the configuration was frozen on 1 Mar. 1978.

In addition the supply the vehicle, we had to develop + supply a guidance system, a passive navigation system and modify the turbofan engine for installation and flight profile.

We ran a mini competition for a guidance system and selected the St. Petersburg div of Minn. Honey. to develop and deliver prototype system. It was necessary for M-H to design a passive miniaturized precision guidance. We called the system PRECISE. We cleared only the top mgt + prog. mgr. of each subcontractor and briefed them on Sr. Prom program. Minn Hon completed successfully the develop of PRECISE on $10.5 M cost and schedule.

For the navigation system we first looked at the nav. system on the Boeing ALCM and G.D. Tomahawk cruise missiles. Unfortunately all these cruise missiles used a radar or active type system to generate their map matching system (very similar to terrain follower) and it emitted a signal, we could not use it. The only system or concept at the time was a passive laboratory research program using Radiometric Area Correlation being developed by Lockheed Missiles + Space Co. (LMSC). We therefore gave LMSC a contract to design, develop and demonstrate a prototype radiometric system. The system used a radiometer which would measure the surface temperature gradient of ¼⁰ F and generate a map that could be correlated to a map generated by the Defense Mapping Agency acquired by satellites. In this manner a “fix” could be attained throughout the route planned and navigation toward a target could be accurately made. To check the system out it was necessary to have a modified NASA Convair CV-990, operated by the Sk Wks, to flight test the prototype RAC system. The test flights began on 31 Aug 79 through 30 Apr. 1980. A total of 51 flights over continental U.S. and Canada. IT was necessary to fly the RAC system of all types of terrain, all types of weather, all times of day over land and water and all seasons of the year, since the generated maps dependant on the accurate measurement of temperature gradients. LMSC produced 4 RAC systems at a cost of $8 M. The system was late by about 6-9 months, however it did overcome a majority if its problems. The system was later used in the TASM program at Northrop after the Sr. Prom program was terminated.

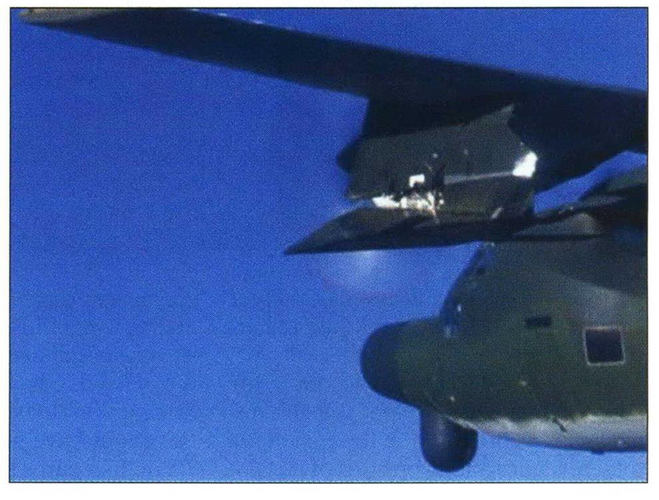

As part of the test program, we had to acquire a DC-130H, used to launch Teledyne drones. With help of Sperry-Univac we located a C-130 at Hill AFB at Wendover, Utah. It was necessary to redesign the launch station in the aircraft to meet the instrumentation and launch parameters needed to monitor our ATCM. It was necessary to modify the pylon and launch rack, since our requirement was to launch from a B-52 or B-1A aircraft. The purpose of the C-130 was to check out the launch, monitor the cruise and then execute the recovery system. As a backup it was necessary to duplicate a ground system in a van, that would duplicate all the systems in the C-130, collect all the telemetry data throughout the flight and act as a backup should the C-130 and the ATCM lose data link contact.

The launch rack had to be designed to handle our vehicle. It had to provide adequate clearance for our configuration, fit our attachments and structure, withstand our unique loads and yet had to be B-52 compatible, the ultimate goal of our vehicle, but the attachments had to be unique since those that were on our ATCM had to be retractable and covered over after launch to achieve our stealth requirements.

We contracted with Sperry-Phoenix to design our remote piloting data link and flight control system. We ordered 9 flight control systems.

We started out with 18 people in Phase I, 15 engrs. and 3 shop personnel. Senior Prom was the first vehicle to ever utilize Computer Aided Design (CAD) system. We had to be sure that our design system was compatible with Lockheed Georgia so that when we ever went to production, we could produce the airframe in Ga. I planned to use the Burbank facility for Senior High II, the fighter program later called Senior Trend. As we completed the design by the end of 1978, we had 193 on the program (86 engrs + 107 shop; by the end of 1979 as we produced the 9 vehicles (7 flight and 2 ground test) we reached our max. head count of 217 (103 engr. and 168 shop) The engineers included, designers, wind tunnel testors, dynamic ground test and flight test

We began Phase II in 15 Oct 1977, planning our first flight for July 1979.

As we continued aerodynamic wind tunnel tests and RCS model test, we achieved a fairly neat configuration. We were achieved L/D greater than 11, which allowed us to get our range and our RCS was lowest we had seen. The vehicle had its rudder control surface at the wing tips. We started to manufacture this configuration having frozen the design in Mar 78 based on W.T. and RCS tests. We developed a ground simulation testor at Rye Canyon which would simulate the entire flight profile from launch, cruise and recovery; we were able to take a ground test vehicle, put on this CARCO table. At the same time, we completed the redesign on the DC-130 launch vehicle and put the second vehicle on the pylon beneath the wing and exercise the flight control system in a capture mode. We developed a parachute recovery system so that at the end of cruise recover safely land land the vehicle to be refurbished for reuse. Since our contract stated we had to achieve 10 successive launch, cruise, flights before we got our Phase III (production contract) and we had only built 7 flight vehicles. The parachute design and stowage was not part of the production configuration, but it was one of the most difficult and would give us a lot of problems. The design required a large parachute to retrieve the 1500 lb empty ATCM. This large parachute had to packed very compactly and stowed in the main fuel tank. Then design a pyrotechnic system that would cut a large hole in fuselage below the tank, so that chute could be ejected and the drogue and main chute could be unfurled and deploy allowing the vehicle to land softly on ground. We ran into numerous pyrotechnic design problems, mainly reliability and repeatability. We had be sure pyrotechnics were safe and reliable and would not damage the vehicle other than replacing the large hole in the outer skin. After many months of test and redesign, we achieve a a design. It was a shame we put so much effort in this because the production ATCM did not require recovery.

As we proceeded with our ground base simulator, we ran into a major problem, which delay the program. Between May-June 1979 we ran into a structural coupling control surface problem. As much as we tried, we failed to find a solution to this problem with our rudder wing tip configuration. In mean time we were running wind tunnel tests and RCS tests to find a new acceptable tail location. On Aug 12, 1979 we stopped the vehicle production of wing rudder controls, and made a major decision to redesign the basic config. and moved the ruddertail to the trailing edge of the fuselage. This gave us much better stability and resolved our structural coupling problem. The results in aerodynamic performance of new config. was negligible and our RCS signature increased less than 1 db. Our launch weight for the new design increased 100 lbs or 2600 lbs, with 1000 lbs of fuel and maintained our 2000 mi. range. Since the change came pretty late in Phase II, we had to modify most of the vehicles and reduced our flight test prog from 10 to 6, however this was again reversed back to 10 because early tests on new config. were so successful.

We had planned in 1977 to have our first jettisoned vehicle in early 1979. We began our flight test program with mounted vehicle under C-130, to check out the flow characteristics surrounding vehicle and all the attendant loads from takeoff through the point of launch. These were dummy vehicles. We then began a series of flights to check out the launch cycle as well as the recovery. Unfortunately our first four launches were failures. All of these were with our old configuration. Three of the failures were chute failures, the basic vehicle deployed correctly; the first failure resulted from the explosive cord failing to cut open the fuselage panel, so parachute was unable to deploy.

We then had 3 successful jettison flights, the last two with the revised configuration. The last successful jettison launch was in Dec. 79.

As mentioned earlier when we began to program we planned a July 1979 first flight, but due to launch+recovery problems and the redesign of the configuration we moved the launch date to 15 Feb 80, which still was pretty good since it was only 24 months from go ahead. We achieved our first successful launch on 1 Mar 1980 and it did all it was planned to achieve. However we failed to recover vehicle due to a parachute failure. Our 2nd launch was a failure. However our third flight in June 1980 was a total success everything from launch to recovery. We then followed with 9 more successive successful flights – which met the contractual obligation and goal. The overall span of ATCM prototype program was to be 34 months for phases I and II. We actually completed it in 38 months in spite of all our early problems. The entire program including the the development of Precise, RACG, Williams engine + flight vehicles was $103 M. The met the contractual objective of development + flight test of 10 successful + successive flights, a precision flight control system, a radiometric area correlation guidance system, a modified engine and a production plan for full scale production.

During Phase II, it became evident that the Sr. Prom production program would be more than the Sk. Wks could handle, as we had already began the Sr. High II program. So in consultation and coordination with AF and Lockheed Senior Management, a transition plan was formulated to turn the overall management to Lockheed Missiles+Space Co, the airframe manufacture to Lockheed Georgia, and retain the stealth responsibility at the Sk Wks. So in mid 79, Howard Barnette of LMSC was made Program Mgr. replacing Milt Jantzen at Sk. Wks. Barnette moved temporarily to Burbank, bringing with him a team of about a dozen LMSC personnel to achieve the transition; similarly Ga. design personnel came to Burbank to transfer the design and manufacture of the hardware as well as assist in the flight test program. Therefore on May 8, 1981, the prime contract for Phase IIIA, the full scale development (FSD) was assumed by LMSC; the Sk. Wks acting as technical advisors for low observables and would supply all the specials absorbers and coatings required for the entire program.

There were 10 successful launches cruise flight and retrievals between June 80 and Mar. 81. The first successful stealth test flight occurred on 3 Oct. 1980. During this and subsequent stealth flights, Sr Prom’s RCS either met or favorably exceeded the predicted test. These tests were flown over the dynamic radar test range as well as against threat ground radars, F-15 fighters and AWACS radar system. None of these systems were able t track Sr Prom. The last flight of a Sr. Prom vehicle was made of 13 Mar 81. The new and refurbished vehicle were put into storage. Many proposals were later made to use these vehicles to test the capability of our latest ground tracking radars or the Navy’s Aegis system. However, due to politics and bureaucracy nothing happened.

Phase IIIA began in May 81 with LMSC now running the Sr Prom program’s full scale development from Sunnyvale. Turning the program over to LMSC was one of my biggest mistakes in my Sk Wks tenure. Because once it went North, even though it was a black program, LMSC staffed and ran it like a full blown “white world” program. The staff grew by hundreds, an integration program to launch the ATCM from the B-52 was given to Boeing, and a full blown hardware program was set up in Georgia. The program cost grew to a billion dollar program and the unit cost of the missile more than doubled. As a result in late 82 or 83, Dick Delauer, head of ODRE decided to consolidate the various cruise missile programs and decided it couldn’t afford the current Sr. Prom and terminated the FSD program. The Wright Field Low Observable SPO was directed to run a competition to design and develop a low-cost advanced Strategic Stealthy Cruise Missile. LMSC, Northrop and Gen Dynamics bid the program. G.D. in San Diego won the competition. Another competition was again setup but this time for a Tactical stealthy missile. The same competitors bid. LMSC with the Sr. Prom looked like they had an advantage, but their costs were too high. Northrop won this contract. We may have been lucky to lose. This program was called TASM. LMSC won contract to build the passive guidance system, also on a fixed price basis. Northrop failed to meet performance, cost or schedule and has lost about $200 M so far and is still not operational. LMSC has also lost money on their portion. The DOD has come numerous times come close to cancelling the program.

In summary, the prototype phase of Sr. Prom performed by Sk. Wks was very successful. We got numerous commendations from the Air Force for our performance. We achieved all our 4 basic objectives. We developed a configuration, which met its aerodynamic and RCS signature predictions, and developed all the subsystems. We completed our part of the program within four months of the original plan set nearly three years previously. Cost growth of less than 19% which was considered very modest considering the state of the art advances achieved and the technical difficulty of the task. Security was maintained throughout the program, even to this date, which involved several major subcontractors, the use of diverse and complex Govt resources and testing at a remote location. The level of RCS were some of the best ever achieved by any program to date.

(See Passon’s comments on Sr. Prom also)