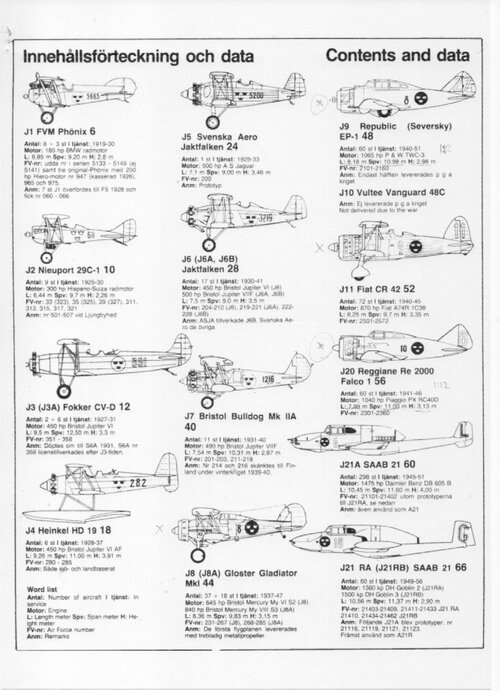

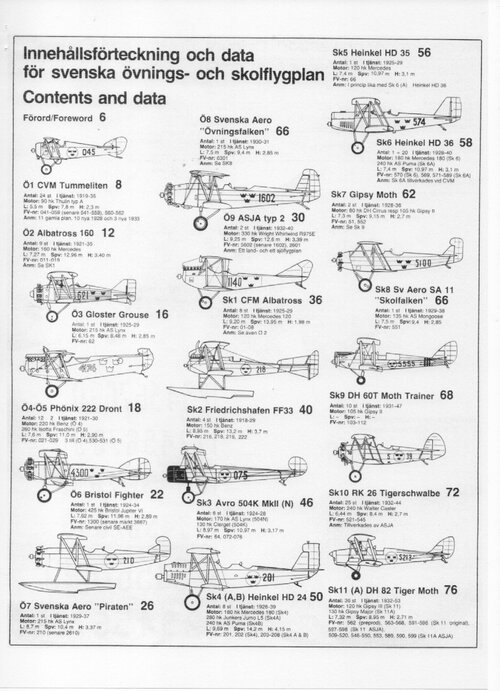

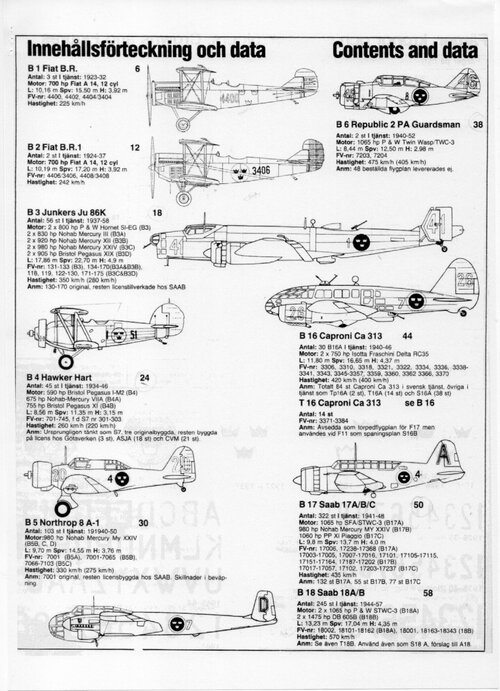

In 1919, the Swedish Army had an aircraft division formed by twelve war surplus Phönix D.III fighters joined by twenty-four FVM Ö1

Tummelisa advanced trainers in 1921.

Four years later they acquired ten units of the Nieuport-Delage NiD 29 ex-French fighters. The Swedish Air Force (

Flygvapnet) was created in 1926, unifying Army and Navy aviations. The new service required the use of two-seat long-range fighters. They acquired fifteen Fokker C.Vd in 1927 and the following year six Heinkel HD 19 seaplane fighters.

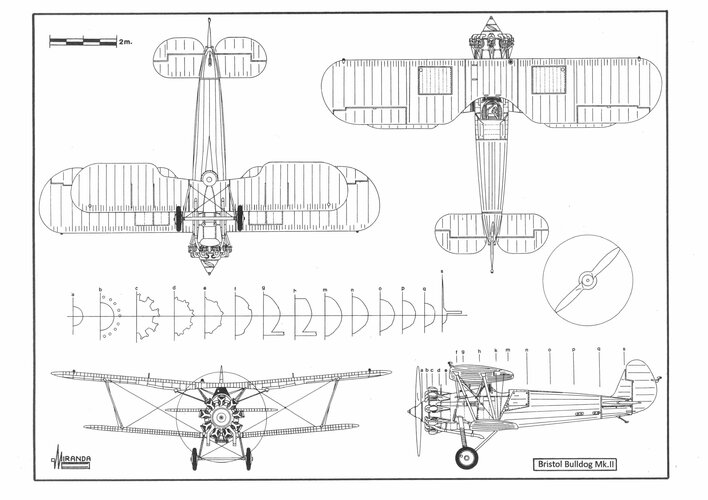

The weapons race started by the Soviet Five Years Plan in 1928, prompted the countries close to the U.S.S.R. to modernize their combat aircrafts. After the entry into service of the Polikarpov I-3, in August 1929, Lithuania ordered fifteen Fiat C.R. 20 fighters and Latvia seven Bristol Bulldog Mk.II. In Mach 1930 the prototype of the first Polish monoplane fighter P.W.S.10 flew for the first time and four months later the prototype of the Polikarpov I-5. At that time the VVS already had two-hundred-and-fifty I-3 in service.

In August Sweden ordered three Bristol Bulldog Mk.II and eight Bulldog Mk.IIA (286 kph) fighters in May 1931. That same year the Swedish Government ordered the construction of 18 units of the indigenous fighter Svenka Aero

Jaktfalk. The VVS fighter strength was of three-hundred-and-eighty-nine I-3 and sixt-six I-5. In 1932 the expansion of the

Flygvapnet was planned, with the construction under licence of thirty-six Tiger Moth and twenty-five

Tigerschwalbe elementary trainers, joined by ten

Sparmann S-1A advanced trainers in 1934.

Between 1936 and 1938, the U.S.S.R. made a demonstration of force by sending to Spain hundred-and-eight Polikarpov I-15, ninety-three Polikarpov I-152, ninety-three Polikarpov I-16 Type 5, sixty-eight Polikarpov I-16 Type 6, hundred-and--twenty-four Polikarpov I-16 Type 10, thirty-one Polikarpov R-5 Army cooperation airplanes, thirty-one Polikarpov R-5 Cht strafers, sixty-two Polikarpov RZ light bombers and ninety-three Tupolev SB-2 medium bombers. They also sent 347 tanks, 60 armoured vehicles, 1,186 cannons, 340 mortars, 20,486 machine guns, 497,813 rifles, 862 millions of cartridges, 3.5 millions of artillery shells, 10,000 aviation bombs and four torpedo boats.

Lithuania ordered thirteen Dewoitine D.501 L monoplane fighters.

With the publication of the Defence Act in December 1936, the second plan of expansion of the

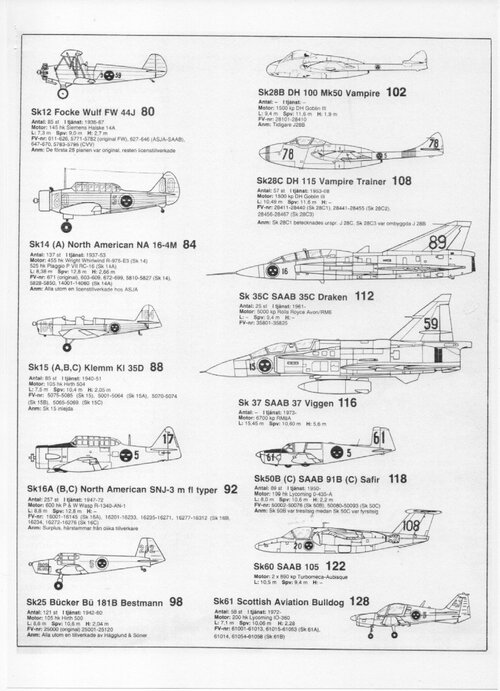

Flygvapnet to five combat wings was started. To equip these units with enough airplanes it was necessary to organize the indigenous production of forty-two Hawker Hart light bombers, eighty Junkers Ju 86 K-1 medium bombers, hundred-and-two Douglas 8 A-1 attack bombers, hundred-and-ninety SAAB 17 dive bombers, eighty-five Focke-Wulf Fw 44 elementary trainers and hundred-and-thirty-six North American NA-16-4M advanced trainers, which should be delivered between 1937 and 1941.

At 1937 the VVS strength was of 8,139 front-line aircraft, including 443 medium and heavy bombers. The Polikarpov I-152 started fighting in China.

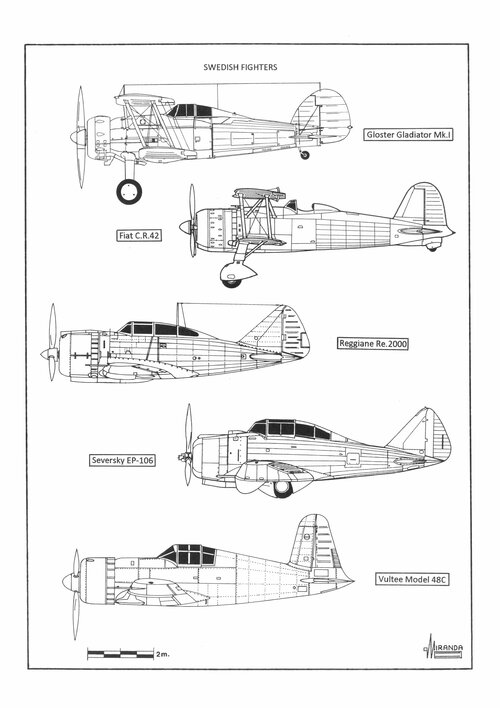

In June, Sweden ordered thirty-seven Gloster Gladiator Mk.I fighters. In 1938 the production of Polikarpov I-153 started and Sweden ordered eighteen Gloster Gladiator Mk.II (414 kph). At the end of that year the Soviet aviation was defeated in Spain thanks to the technological superiority of the Legion Condor.

On 11 May 1939, the VVS entered into combat against fighters of the Imperial Japanese Army in Khalkin Gol. In September, the Soviets were forced to sign an armistice, overcome by the technical quality of Japanese planes and pilots.

On 29 June, Sweden ordered fifteen Seversky EP-1-106 fighters.

After its defeat in Spain the U.S.S.R. was also forced to sign the German-Soviet non-aggression pact and be satisfied with 'freeing' weaker objectives by occupying eastern Poland when the Polish Army had already been defeated by the Wehrmacht. That same month the ANBO VIII indigenous dive bomber took its first flight in Lithuania and its Government ordered thirteen Morane-Saulnier M.S.406 fighters that the French never delivered because of the war. Nor did the British deliver the Spitfires acquired by Estonia or the Hurricanes acquired by Latvia.

On 11 October Sweden ordered a second batch of forty-five Seversky fighters.

Despite the losses suffered in Spain, Manchuria and China, the VVS strength was of 7,320 aircrafts. On 30 November, the Soviets began the invasion of Finland. At that time the

Flygvapnet possessed a front-line strength of only 140 aircraft (of which about one half consisted of Harts and Gladiators biplanes) but went to their aid forming the

Flygflottilj 19

, a volunteer unit with four Hawker Harts and twelve Gladiators equipped with skis undercarriages.

On 1 January 1940 the Swedish Government ordered a third batch of sixty Seversky EP-1-106 and two Republic 2PA attack bombers. On 6 February, they also ordered hundred-and-forty-four Vultee Model 48C fighters but, fearing that the airplanes might fall into Soviet hands, the U.S. State Department placed an embargo on the export of military aircraft to Sweden on 18 October.

The embargo also included the export of engines, so the Douglas 8 A-1attack bombers had to use the Bristol Pegasus XII, the SAAB 17 used the Bristol Pegasus XXIV and the Piaggio P.XII bis RC 40D and the North American trainers used the Piaggio P. VII RC 16, less powerful and reliable than the original Pratt & Whitney and Wright Whirlwind. The situation derived in panic and the Swedish Government ordered seventy-two Fiat C.R. 42 bis and sixty Reggiane Re.2000 fighters from Italy, as stop-gap solution until the indigenous industry could build their own fighters.

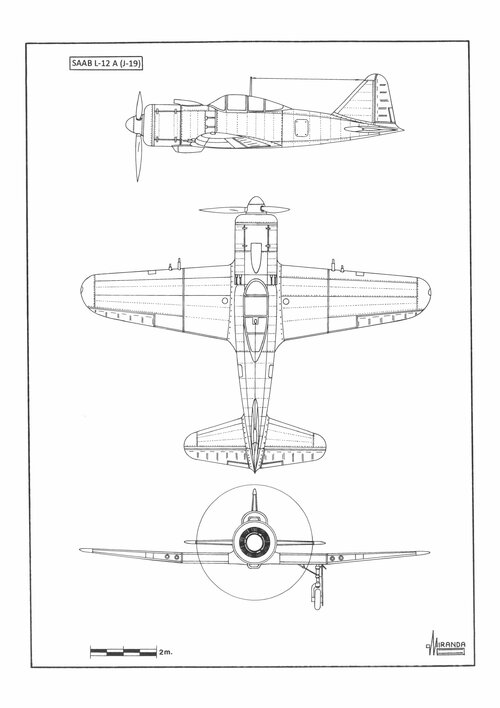

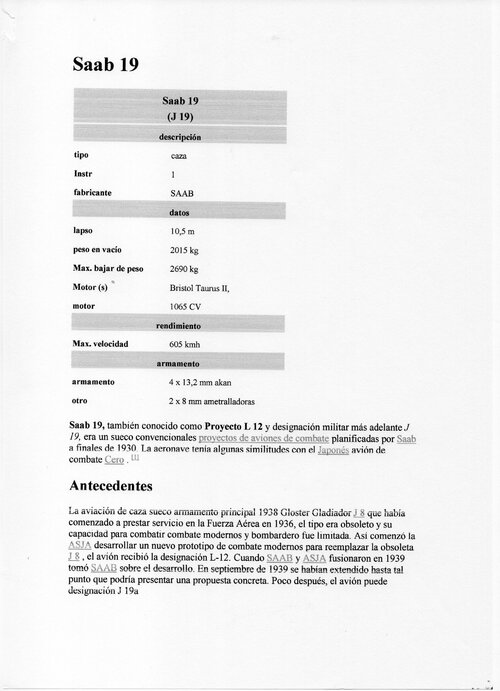

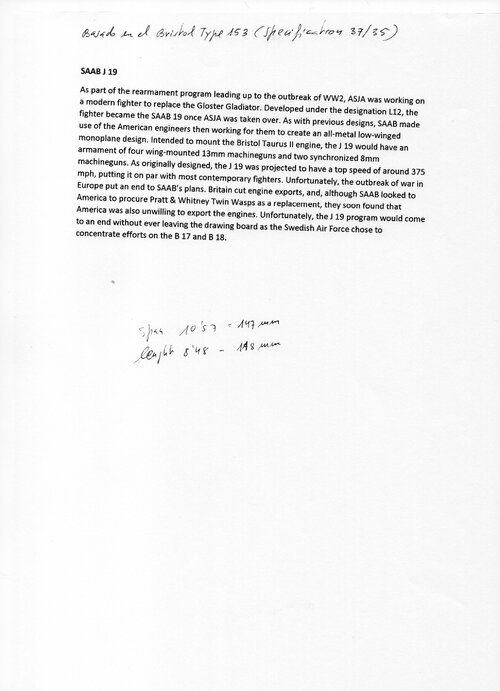

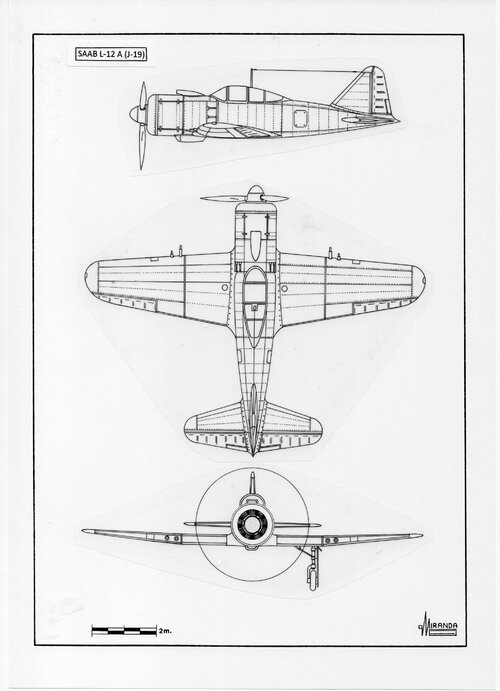

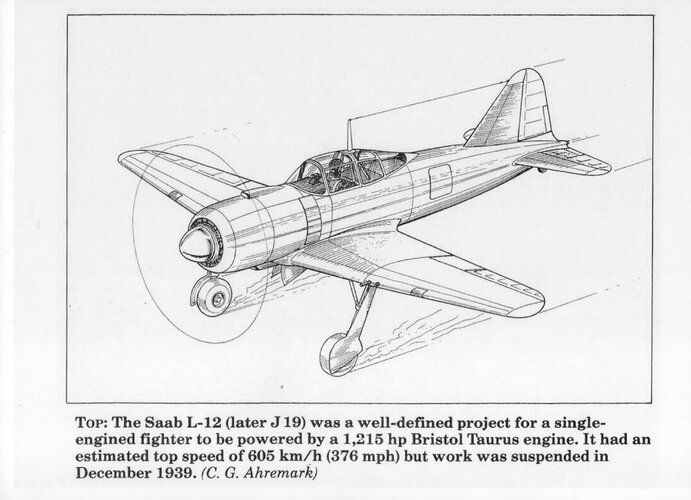

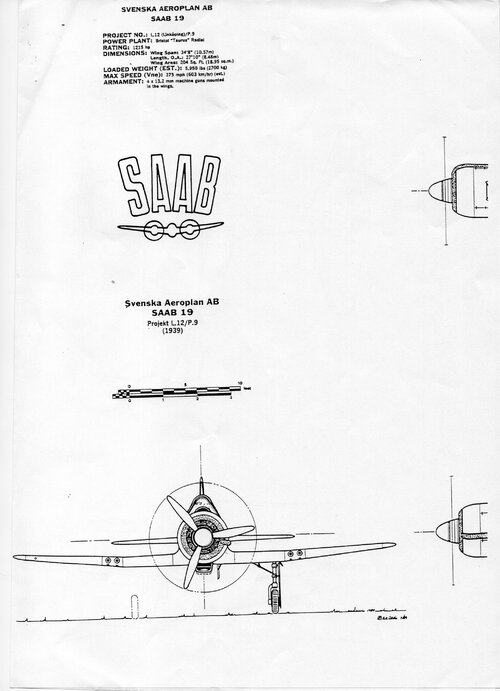

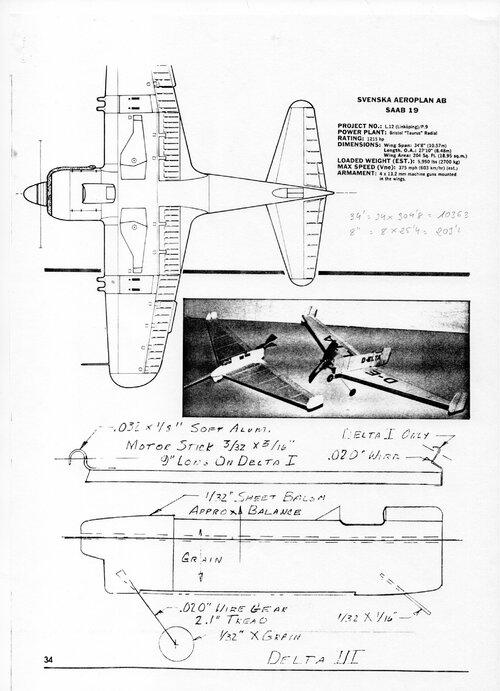

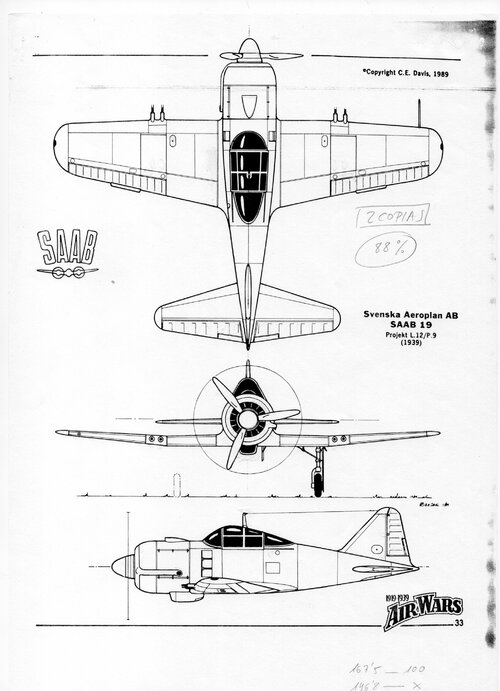

Unfortunately, the SAAB 19, a project of fighter based on the Bristol Type 153, whose manufacture was started in 1941, had been cancelled when the British rejected to continue the production of the 1,400 hp Bristol

Taurus II engine. The SAAB 19 would have been a low wing monoplane with 10.5 m wingspan, all-metal construction, retractable undercarriage and armed with four wing-mounted 13.2 mm m/39A machine guns. Its estimated maximum speed would have been 605 kph and his maximum take-off weight of 2,690 kg.

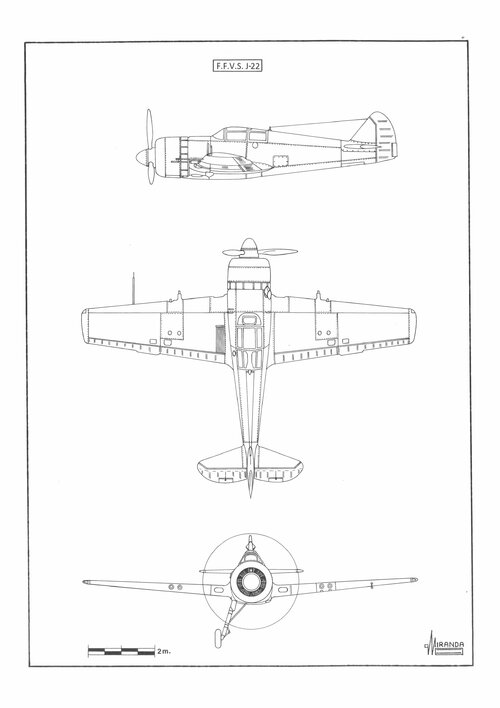

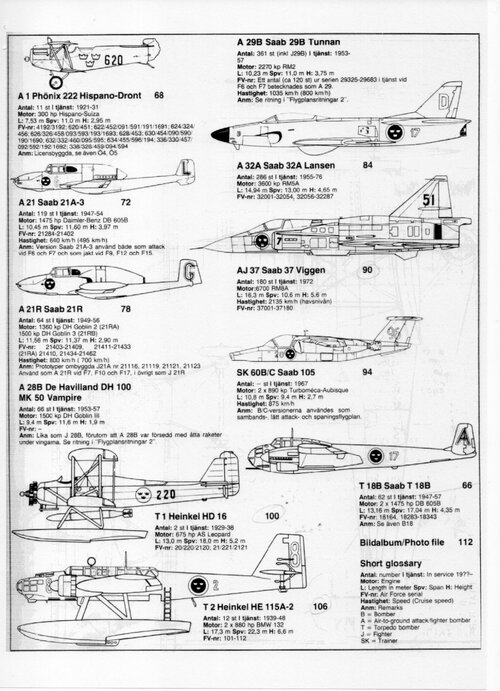

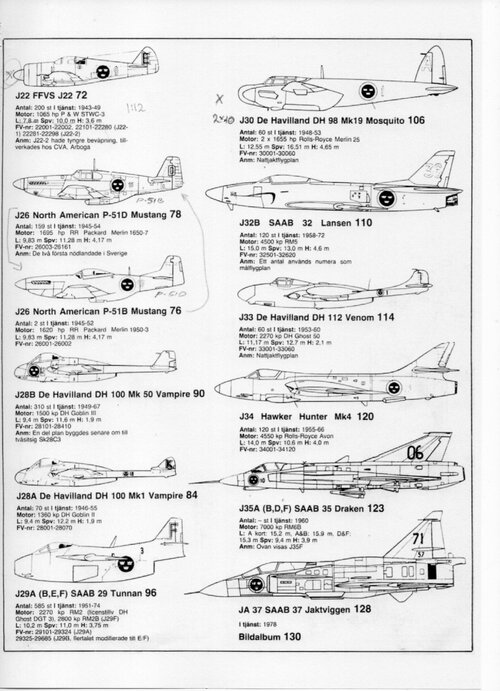

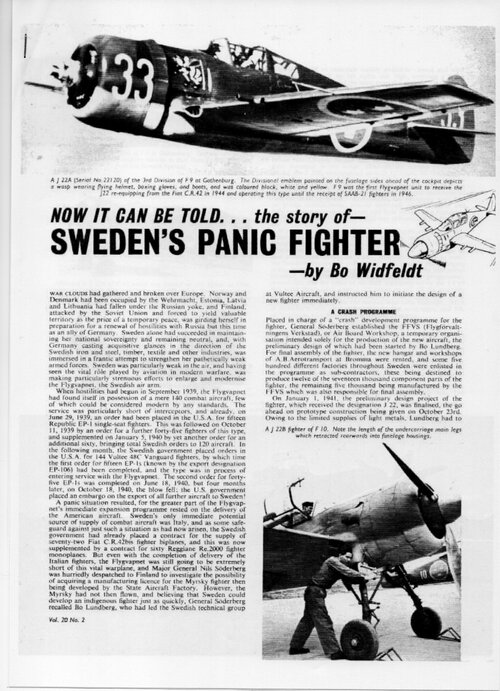

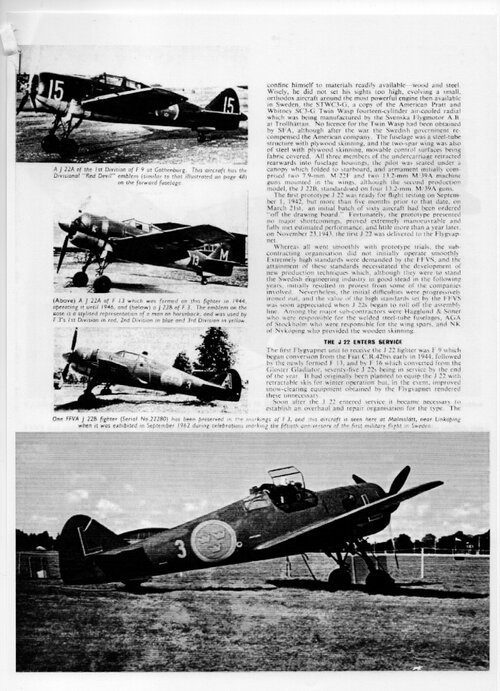

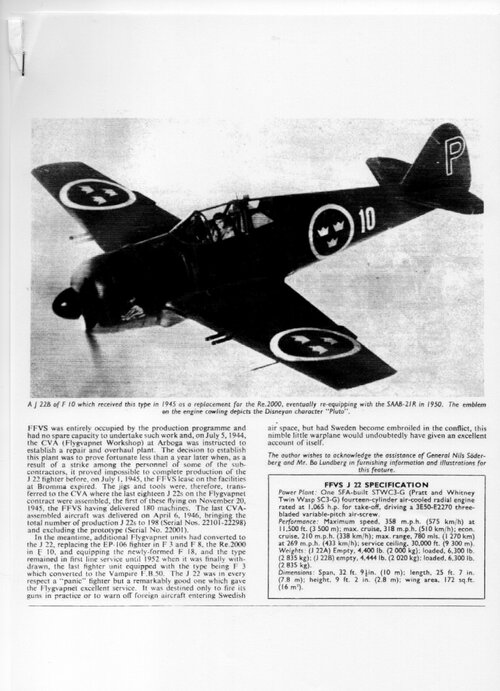

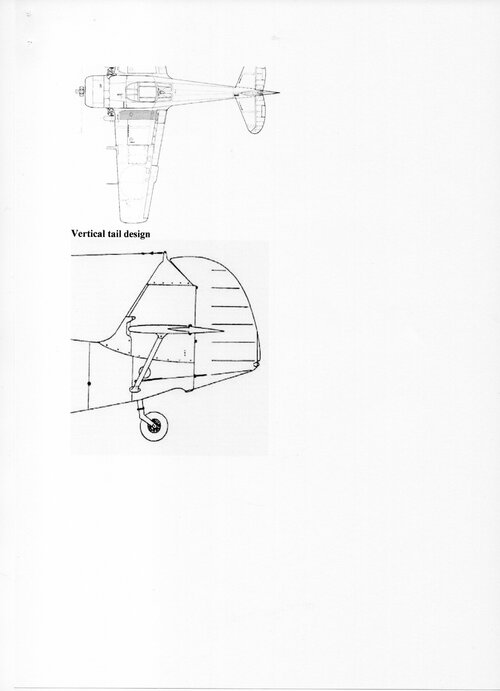

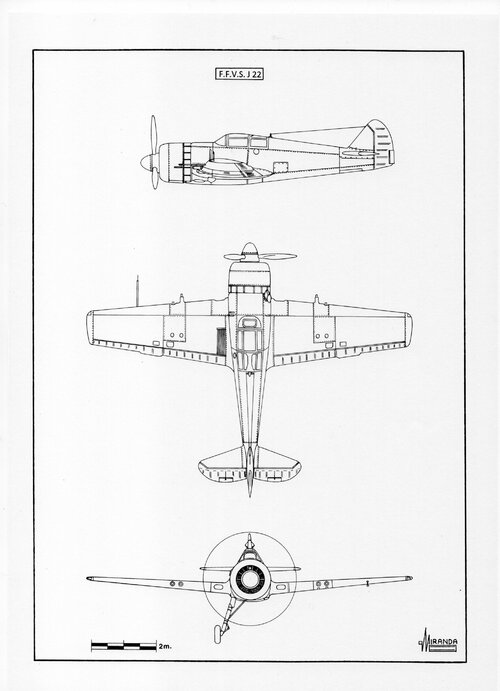

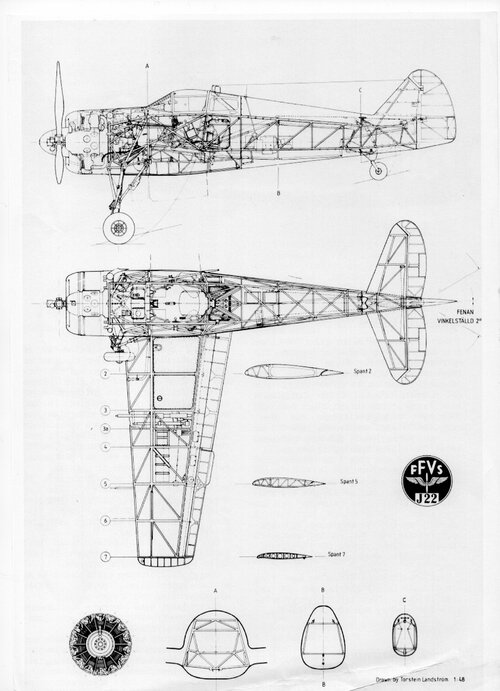

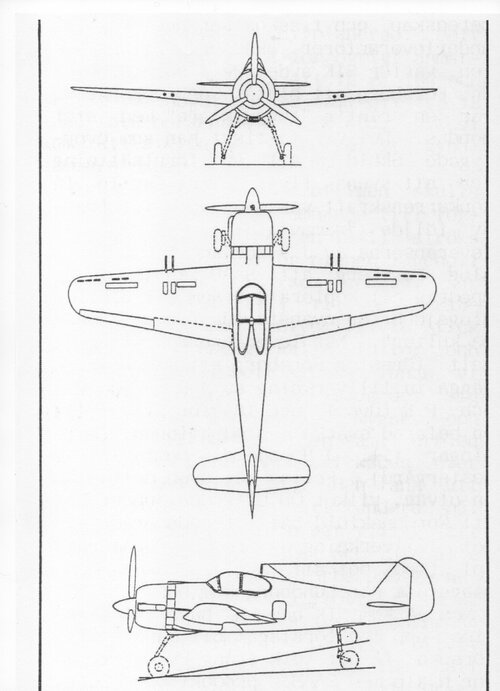

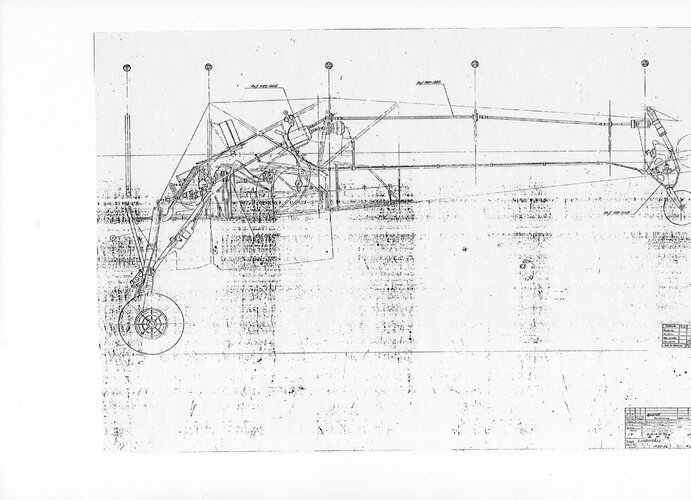

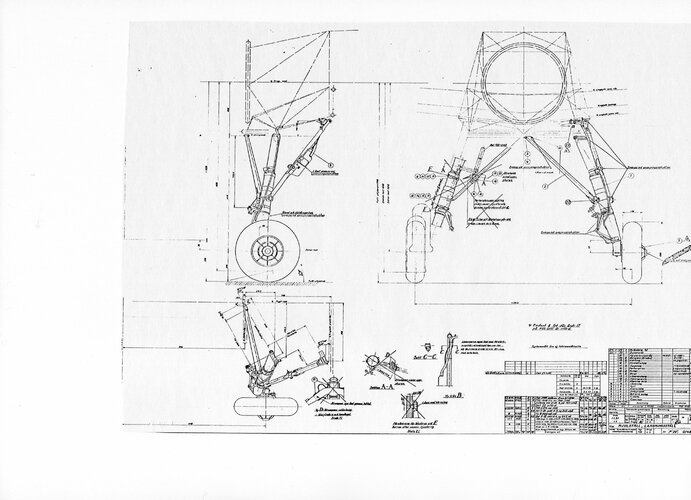

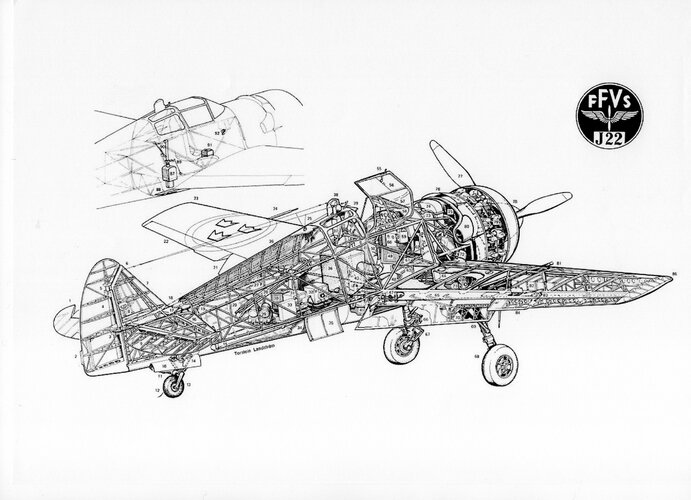

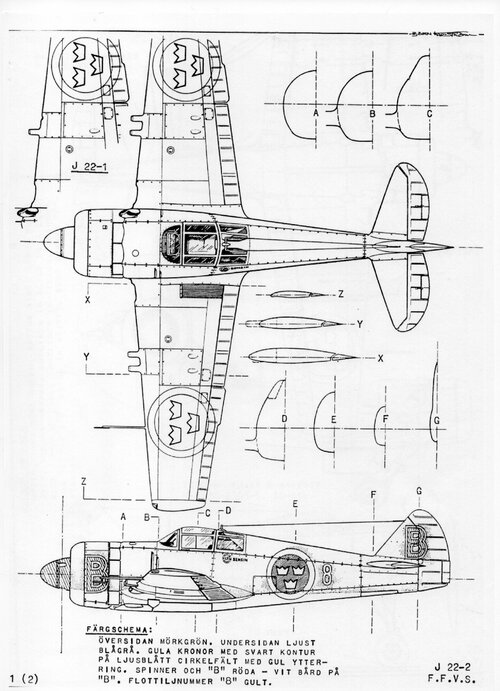

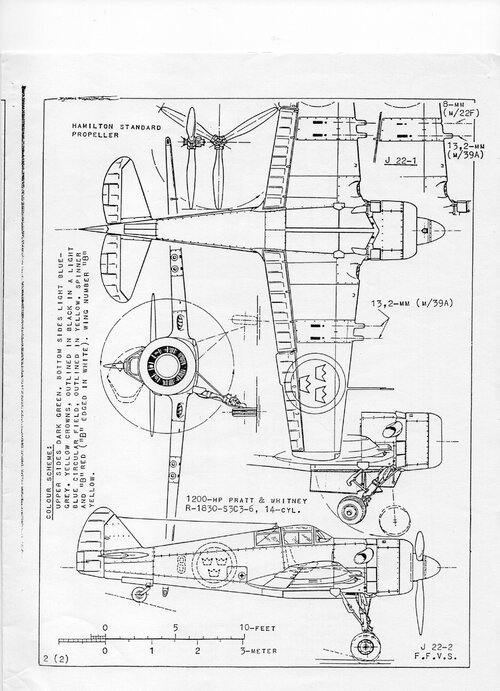

On 1 January 1941, the design work of the J 22 'panic fighter' was started, under the leadership of Bo Lundberg. The General Nils Söderberg established the FFVS workshop, to temporary organisation intended solely for the production of the new aircraft. As the Swedes expected to get the fighters in the USA, all available aluminium 2024 T3 was already being used in the production of the S 17 and S 18 bombers.

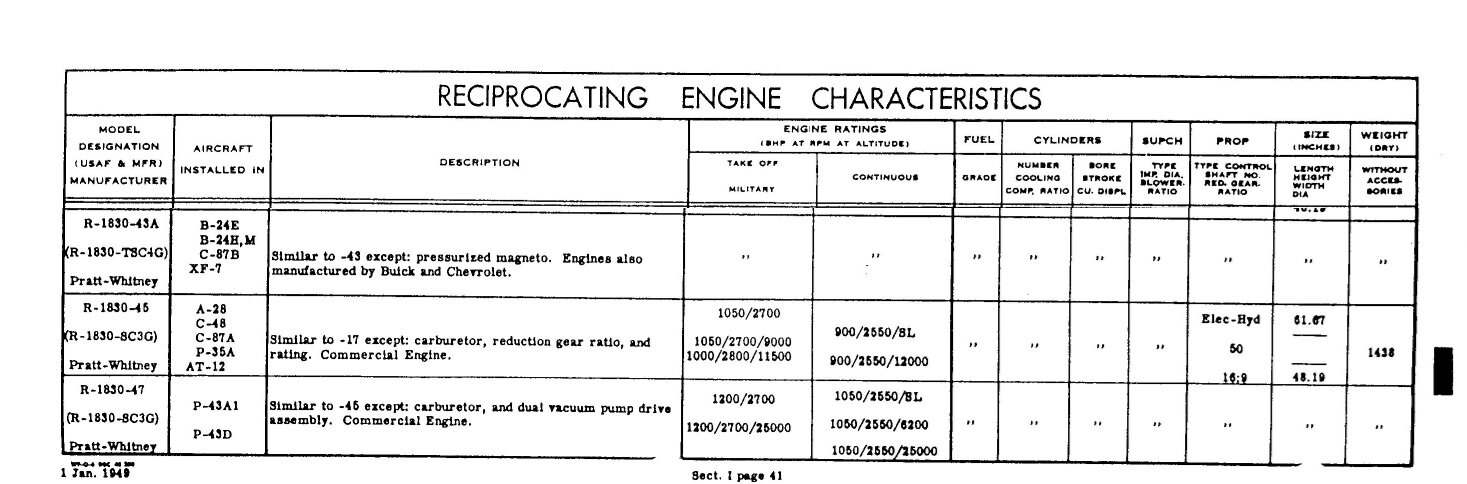

The construction system of the J 22, based on that of the Finnish

Myrsky, consisted of welded Chrome-Molybdenum steel tube structure covered with plywood panels. To circumvent the engines embargo, Sweden managed to purchase a batch of 100 Pratt & Whitney R-1830-45 Twin Wasp engines in 1942, from the Vichy-French Curtiss H-75 fighters, and

Svenska Flygmotor-Trollhättan started an programme to copy the

Twin Wasp as the Swedish-made 1,050 hp STWC-3G.

The J 22 prototype made its first flight on 20 September 1942, reaching 575 kph.

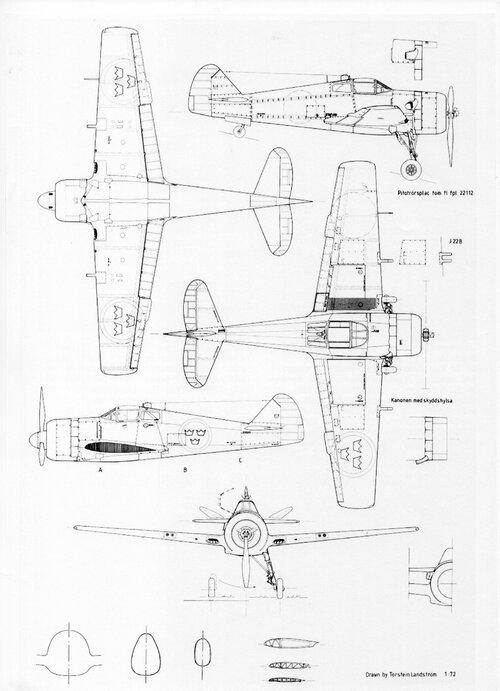

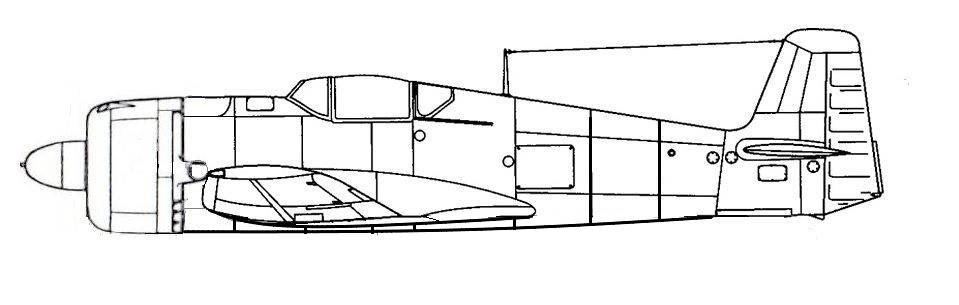

Between 1943 and 1946, 198 units were built. Of these, the first 143 units were J 22 A (with two 13.2 mm m/39A and two 7.9 mm Bofors m/22F machine guns) and 55 units of the J 22 B version (with four m/39 A). The J 22 was light and very manoeuvrable fighter equivalent to the Spitfire and Messerschmitt Bf 109 of 1940, but it could not compete with the latest German and British designs when entered service.

This did not represent a serious problem as Sweden already maintained good relations with both and the J 22 exceeded or equalled the Soviet fighters Polikarpov, LaGG, Hurricane Mk.II and Airacobra that posed the real threat. In March 1941, the

Flygvapnet Air Board managed to reach an agreement for

SFA-Flygmotor licence manufacture of the German Daimler-Benz DB 601 engine. Subsequently the licence upgraded to the latest version DB 605B with 1,475 hp. The new engine was acquired to improve the performances of the SAAB 18 bomber and to propel the fighter that would replace the J 22. On 5 April 1941 the design team of SAAB, under the leadership of Frid Wänström, proposed the construction of the J 21, an unconventional fighter with twin tail booms, nose wheel and pusher propeller.

The radical nature of the new fighter presented unknown development problems: the technological risk of the design of a high speed laminar flow wing, the serious cooling difficulties of the radiator installation buried inside of the wing (that never really overcome), the adoption of a nose wheel that required to train the pilots again using a specially modified North American NA-16 and the development of the SAAB-Bofors Mk.I ejector seat to prevent the pilot from being hit by the airscrew during the bail out.

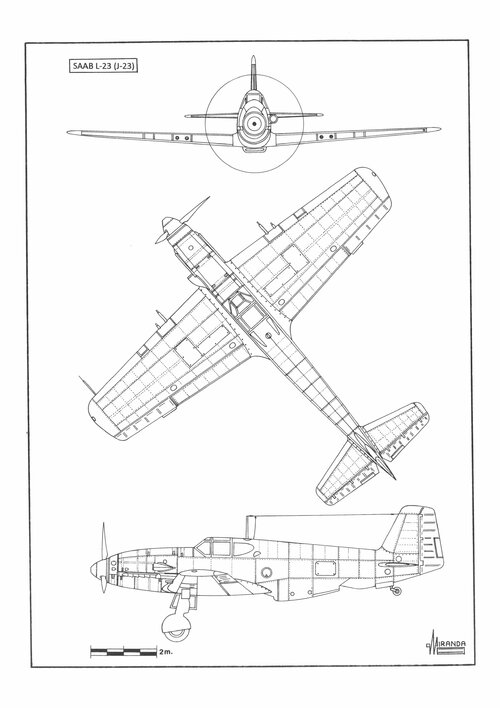

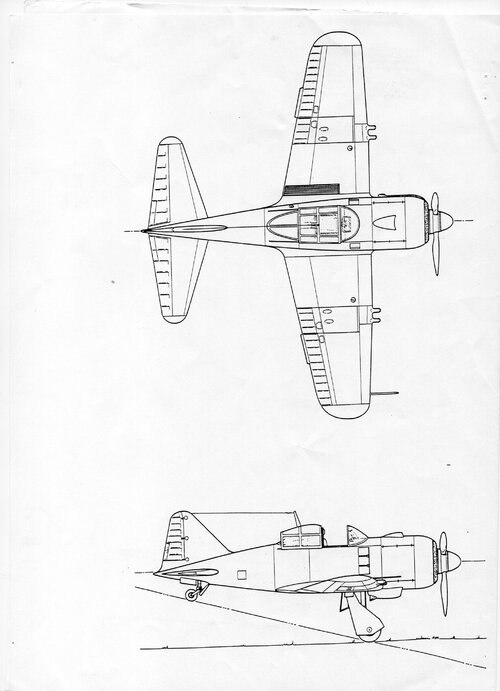

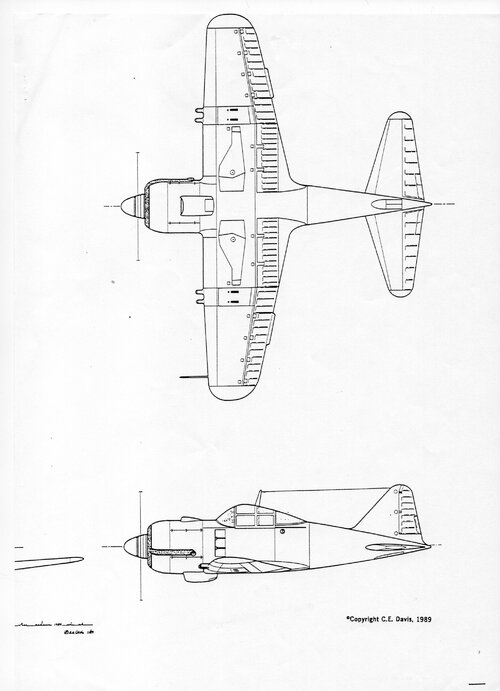

In October 1941, fearing that the J 21 presented insurmountable development difficulties, the

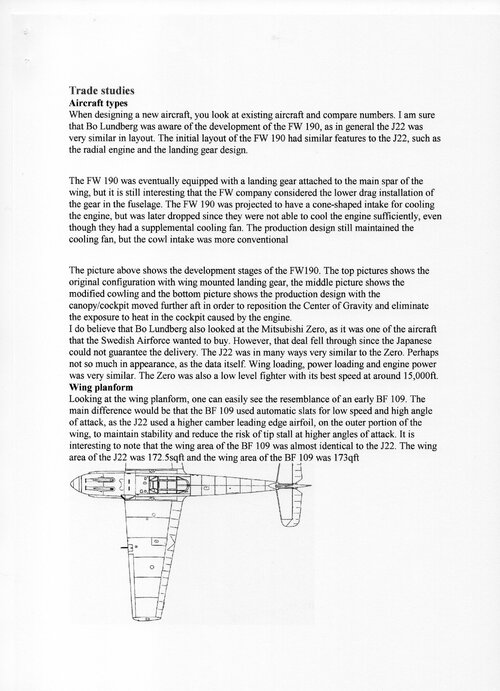

Flygvapnet suggested the design of a more conventional fighter, as a fall-back option, and the SAAB J 23 parallel project was proposed on November. It was a low wing monoplane with 11.28 wingspan, all-metal construction, conventional landing gear and armed with a 20mm Bofors M/45 engine-mounted cannon and four 13.2 mm Bofors m/39A wing-mounted machine guns.

The J 23 would be propelled by one DB 605B driving a VDM propeller and cooled by one Mustang-style ventral radiator. Wind tunnel tests in the Technical High School-Stockholm showed that the J 23 would have superior maximum speed and climb, but the J 21 was more manoeuvrable thanks to the central position of the engine. When the J 21 development problems were surmounted, the J 23 design work was discontinued on 5 December 1941.

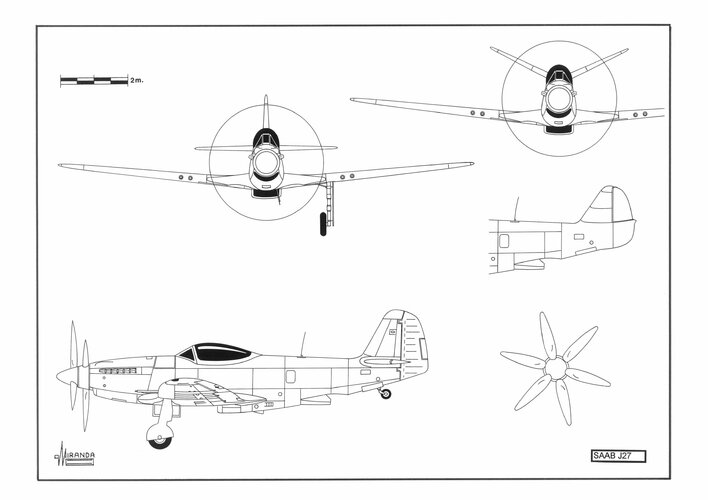

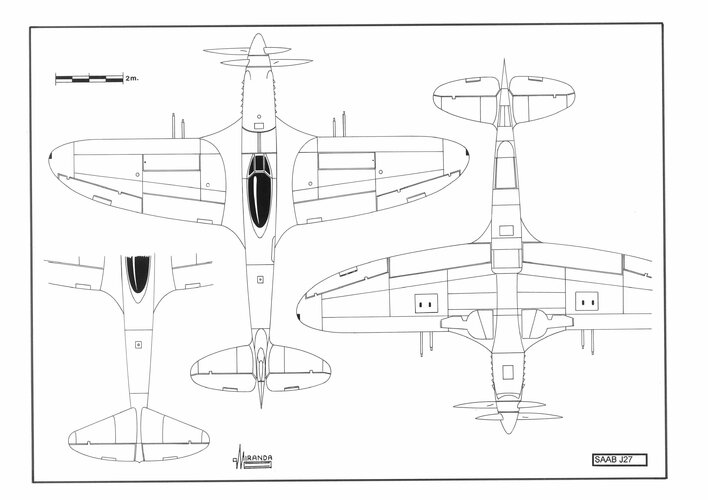

At the end of 1944 the latest models of German and British fighters already reached speeds that the J 21 could not match, because of the excessive drag generated by their tail surfaces. In April 1945, SAAB started the design work on the J 27, a conventional fighter with elliptical wings, Youngman flaps, tear drop canopy and ejector seat, capable of flying at 700 kph powered by a 2,200 hp Rolls-Royce

Griffon engine driving contra-rotating airscrews.

The foreseen armament was four 13.2 mm Bofors-Colt m/39A wing-mounted machine guns.

It was expected to build a more advanced version, with butterfly tail, four 20 mm Hispano cannons and 740 kph maximum speed, when the 2,500 hp

Svenka Flygmotor AB Mx would be available, a 54 litres engine with 24 cylinders in 'X' configuration to be ready in 1947.

At the end of 1945 the

Flygvapnet chose one

brute force solution, acquiring the manufacture license of the Havilland Goblin Mk.II British turbojet (1,360 kg thrust), to power an advanced version of the J 21 that flew at 800 kph in 1947.

Bibliography

Books

Davis, C.,

Aircraft Three View Drawings for Collectors, B.C.F.K. Publications, 1989.

Di Terlizi, M.,

Reggiane Re.2000 Falco, Héja, J.20, Aviolibri Special 6, IBN Editore, 2002.

Punka, G.,

Reggiane Fighters in action, Aircraft nº 177, Squadron/ Signal publications, 2001.

Davis, L

., P-35, Mini in action number 1, Squadron/ Signal publications, 1994.

Cattaneo, G.,

Reggiane Re.2000, Profile Nº 123.

Cattaneo, G.,

Fiat C.R. 42, Profile Nº 16.

Wildfelt, B.,

The SAAB 21 A & R, Profile Nº138.

Crawford, A.,

Hawker Hart Family, Casemate Publishers, 2008.

Publications

Green, W., “A SAAB half-century”, Air Enthusiast/Thirty-Three.

Billing, P., “A fork tailed Swede”, Air Enthusiast/Twenty-Two.

Sgarlato, N., “Le Fiat C.R. 42”, Le Fanatique de l’Aviation Nº 166 to 169.

Waligorsky, M., “Adventures into the Esoteric”, IPMS Stockholm Magazine, 2002.

Knutsson, G., “SAAB J 23”, Flyg Specialnummer Nº20, 1945.

Drawings from SAAB Svenska Aeroplan Aktiebolaget, Linköping, 1946.

Drawings from Bo Wildfelt, Chuck Davis and Torstein Landström.