nuuumannn

Cannae be ar*ed changing my personal text

- Joined

- 21 October 2011

- Messages

- 276

- Reaction score

- 538

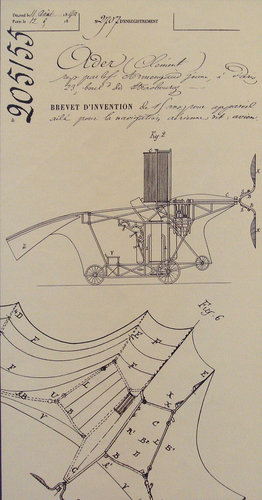

Following from an analysis I have written on this aircraft, I though I might share some information and images I took whilst visiting Paris last year. The following text accompanying the images comes from an article I wrote on the subject.

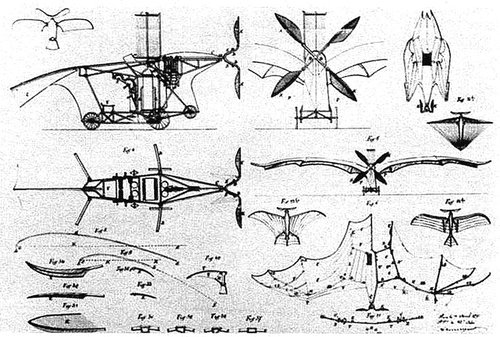

Completed in 1897, today the Avion III hangs from the ceiling of a grand staircase in the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris, re-covered and refurbished and as captivating as it was on its first unveiling. Configured to look like an organic creature, this was deliberate as Ader had seen birds-of-prey circling high in the desert skies of North Africa and had derived ideas of fight from watching them. Allegedly modelled on a fruit bat, in descriptions of the Avion III’s working mechanisms Ader uses biological terms; fingers, arms, elbows, shoulders - as the lexicon of the aeronautical engineer had yet to be invented. Comprising a central rhomboidal cage in elevation and resembling two isosceles triangles butted together at their shortest edge, the rearmost tapering to a sharper point than the foremost, in planform, the Avion IIIs fuselage abruptly widened to a horizontal double pronged structure resembling the horns of a giant minotaur from above. Constructed of split laminated bamboo, the primary construction medium of the entire aircraft, the structure was enclosed in permeable silk, with an opening to the rear of the tapered rear section for the occupant.

Avion III fuselage

Avion III fuselage

A flat pan seat was provided and was open to the elements, the occupant’s feet mounted in stirrups outside the fuselage at the lower forward edge of the enclosure. These actuated the machine’s only moveable control surface, a large fabric vertical rudder. Mounted midway up a vertical framework ahead of the seat were two wheels that actuated an alteration of the wing camber in flight via cables. The only form of instrumentation was a prominent pressure gauge mounted ahead of the occupant.

Avion III cockpit

Avion III cockpit

Its undercarriage comprised three wheels of standard wire braced construction with rubber tyres arranged in a reverse tricycle layout, the front wheels mounted at the widest point of the fuselage ahead of the engine bay, with the rearmost wheel mounted directly forward of the rudder. This was configured to actuate with the rudder’s deflection. Designed to be independently castoring, the wheels could be locked into running straight.

Avion III fuselage rear view

Avion III fuselage rear view

Its novel lightweight steam engine, two separate devices coupled together to drive a propeller each sat ahead of the occupant enclosure, with a boxy heat exchanger protruding above the upper fuselage into the airflow. Each engine comprised two cylinders, high and low pressure and were mounted in tandem as a single unit. Each bank of two pistons extended at right angles upwards and outwards from the firebox assembly and actuated connecting rods, to which were coupled the propeller shafts.

Avion III engine left side

Avion III engine left side

The motor was configured to produce 15 kg or 16 atmospheres of pressure, rotating at a maximum speed of 480 rpm. Bore and stroke was 120mm and 76mm respectively. Weighing a combined total of 117kg, the engine was a masterpiece of weight conservation; its two-cylinder banks weighed a total of 42kg, the firebox and boiler weighed 60kg and the condenser 15kg. With a total of 40hp being produced, this equates to a power to weight ratio of little less than 3kg per hp. Its operator claims the Avion III had a maximum theoretical endurance of four hours, but this is questionable to say the least.

Avion III engine arms

Avion III engine arms

Its twin four bladed propellers rotated on drive shafts mounted within the horns at the upper extremity of the forward fuselage. With a diameter of 2.82m, their pitch was 2m. These were staggered slightly, with the left-hand propeller rotating to the rear of the right hand one. These were made of laminated bamboo, with ribs constructed of canvas paper reinforced with strips of bamboo tapering toward the tips and resembling feathers in profile and curvature. When rotating at speed, the blades flexed outwards, increasing the propeller disc diameter.

Avion III propellers

Avion III propellers

With a total span of 17m, the Avion III’s wing structure followed the layout of that of the fruit bat it emulated, comprising a single spar of hollow laminated bamboo, with what Ader describes as fingers radiating away from a shoulder pivot point approximately midway along the span of each wing. Incorporating an intricately designed hinge, at this point the wing could be articulated to enable it to fold alongside the fuselage for ease of transport and storage. Cables running from control wheels in the occupant’s enclosure to the laterally extending fingers tautened these, enabling the increase of the wing’s top surface curvature. The entire wing surface was covered in permeable silk, which was held in place by tiny fasteners located across the structure at 30 to 50mm intervals. Each silk wing panel weighed 3.5 kg.

Avion III wing

Avion III wing

In conclusion, the Avion III’s system of control was certainly novel and might have enabled some means of control when the wheels were operated differentially, which would have enabled a wing to rise and the opposing one to descend to induce a turn. How effective this might have been depended on the aircraft’s forward speed, which is difficult to predict, given the low power output of its steam engine. The large hinged rudder would have enabled a yawing motion, but the lack of an elevator meant that the only means of ascending and descending was variation of the engine power output, thus affecting the propeller rpm. This all would have made the Avion III a very trying juggling act in flight. In examination of the engine data provided, given that the engine weighed slightly less than its total power-to-weight ratio, the Avion III was terribly underpowered.

Avion III rear view

Avion III rear view

It appears that in conceptualising the Avion III, Ader could not see the wood through the trees – he focussed on complex details that appear baffling in hindsight, but appeared logical to him, yet did nothing to assist in the making of a successful flying machine. In designing his aircraft, Ader carried out little research into airflow, believing that emulation of birds in flight would suffice in building a man carrying flying machine, disregarding the effects of scale on his aircraft. In closing, there is one aspect of Ader’s remarkable creation that lingers to this day; it is the machine that gave the French language its word for aircraft: Avion.

Avion III

Avion III

Information for this article comes largely from Lissarigue’s report titled Ader, Inventeur d’Avions published privately in 1990, sections of which are publicly available through Icare, Revue del’Aviation Française No.134; Le Dossier Ader, written in part by Lissarigue and his fellow colleagues of the Musée de l’Air and published the same year.

Images here: https://www.flickr.com/photos/147661871@N04/albums/72157714763230952/with/50018384551/

Completed in 1897, today the Avion III hangs from the ceiling of a grand staircase in the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris, re-covered and refurbished and as captivating as it was on its first unveiling. Configured to look like an organic creature, this was deliberate as Ader had seen birds-of-prey circling high in the desert skies of North Africa and had derived ideas of fight from watching them. Allegedly modelled on a fruit bat, in descriptions of the Avion III’s working mechanisms Ader uses biological terms; fingers, arms, elbows, shoulders - as the lexicon of the aeronautical engineer had yet to be invented. Comprising a central rhomboidal cage in elevation and resembling two isosceles triangles butted together at their shortest edge, the rearmost tapering to a sharper point than the foremost, in planform, the Avion IIIs fuselage abruptly widened to a horizontal double pronged structure resembling the horns of a giant minotaur from above. Constructed of split laminated bamboo, the primary construction medium of the entire aircraft, the structure was enclosed in permeable silk, with an opening to the rear of the tapered rear section for the occupant.

Avion III fuselage

Avion III fuselage A flat pan seat was provided and was open to the elements, the occupant’s feet mounted in stirrups outside the fuselage at the lower forward edge of the enclosure. These actuated the machine’s only moveable control surface, a large fabric vertical rudder. Mounted midway up a vertical framework ahead of the seat were two wheels that actuated an alteration of the wing camber in flight via cables. The only form of instrumentation was a prominent pressure gauge mounted ahead of the occupant.

Avion III cockpit

Avion III cockpit Its undercarriage comprised three wheels of standard wire braced construction with rubber tyres arranged in a reverse tricycle layout, the front wheels mounted at the widest point of the fuselage ahead of the engine bay, with the rearmost wheel mounted directly forward of the rudder. This was configured to actuate with the rudder’s deflection. Designed to be independently castoring, the wheels could be locked into running straight.

Avion III fuselage rear view

Avion III fuselage rear view Its novel lightweight steam engine, two separate devices coupled together to drive a propeller each sat ahead of the occupant enclosure, with a boxy heat exchanger protruding above the upper fuselage into the airflow. Each engine comprised two cylinders, high and low pressure and were mounted in tandem as a single unit. Each bank of two pistons extended at right angles upwards and outwards from the firebox assembly and actuated connecting rods, to which were coupled the propeller shafts.

Avion III engine left side

Avion III engine left side The motor was configured to produce 15 kg or 16 atmospheres of pressure, rotating at a maximum speed of 480 rpm. Bore and stroke was 120mm and 76mm respectively. Weighing a combined total of 117kg, the engine was a masterpiece of weight conservation; its two-cylinder banks weighed a total of 42kg, the firebox and boiler weighed 60kg and the condenser 15kg. With a total of 40hp being produced, this equates to a power to weight ratio of little less than 3kg per hp. Its operator claims the Avion III had a maximum theoretical endurance of four hours, but this is questionable to say the least.

Avion III engine arms

Avion III engine arms Its twin four bladed propellers rotated on drive shafts mounted within the horns at the upper extremity of the forward fuselage. With a diameter of 2.82m, their pitch was 2m. These were staggered slightly, with the left-hand propeller rotating to the rear of the right hand one. These were made of laminated bamboo, with ribs constructed of canvas paper reinforced with strips of bamboo tapering toward the tips and resembling feathers in profile and curvature. When rotating at speed, the blades flexed outwards, increasing the propeller disc diameter.

Avion III propellers

Avion III propellers With a total span of 17m, the Avion III’s wing structure followed the layout of that of the fruit bat it emulated, comprising a single spar of hollow laminated bamboo, with what Ader describes as fingers radiating away from a shoulder pivot point approximately midway along the span of each wing. Incorporating an intricately designed hinge, at this point the wing could be articulated to enable it to fold alongside the fuselage for ease of transport and storage. Cables running from control wheels in the occupant’s enclosure to the laterally extending fingers tautened these, enabling the increase of the wing’s top surface curvature. The entire wing surface was covered in permeable silk, which was held in place by tiny fasteners located across the structure at 30 to 50mm intervals. Each silk wing panel weighed 3.5 kg.

Avion III wing

Avion III wing In conclusion, the Avion III’s system of control was certainly novel and might have enabled some means of control when the wheels were operated differentially, which would have enabled a wing to rise and the opposing one to descend to induce a turn. How effective this might have been depended on the aircraft’s forward speed, which is difficult to predict, given the low power output of its steam engine. The large hinged rudder would have enabled a yawing motion, but the lack of an elevator meant that the only means of ascending and descending was variation of the engine power output, thus affecting the propeller rpm. This all would have made the Avion III a very trying juggling act in flight. In examination of the engine data provided, given that the engine weighed slightly less than its total power-to-weight ratio, the Avion III was terribly underpowered.

Avion III rear view

Avion III rear view It appears that in conceptualising the Avion III, Ader could not see the wood through the trees – he focussed on complex details that appear baffling in hindsight, but appeared logical to him, yet did nothing to assist in the making of a successful flying machine. In designing his aircraft, Ader carried out little research into airflow, believing that emulation of birds in flight would suffice in building a man carrying flying machine, disregarding the effects of scale on his aircraft. In closing, there is one aspect of Ader’s remarkable creation that lingers to this day; it is the machine that gave the French language its word for aircraft: Avion.

Avion III

Avion III Information for this article comes largely from Lissarigue’s report titled Ader, Inventeur d’Avions published privately in 1990, sections of which are publicly available through Icare, Revue del’Aviation Française No.134; Le Dossier Ader, written in part by Lissarigue and his fellow colleagues of the Musée de l’Air and published the same year.

Images here: https://www.flickr.com/photos/147661871@N04/albums/72157714763230952/with/50018384551/

Attachments

-

Avion III cockpit.jpg346.4 KB · Views: 33

Avion III cockpit.jpg346.4 KB · Views: 33 -

Avion III engine arms.jpg305.7 KB · Views: 32

Avion III engine arms.jpg305.7 KB · Views: 32 -

Avion III engine left side.jpg406.2 KB · Views: 24

Avion III engine left side.jpg406.2 KB · Views: 24 -

Avion III fuselage.jpg400.9 KB · Views: 21

Avion III fuselage.jpg400.9 KB · Views: 21 -

Avion III propellers.jpg333.7 KB · Views: 18

Avion III propellers.jpg333.7 KB · Views: 18 -

Avion III rear view.jpg324.1 KB · Views: 15

Avion III rear view.jpg324.1 KB · Views: 15 -

Avion III wing.jpg360.4 KB · Views: 16

Avion III wing.jpg360.4 KB · Views: 16 -

Avion III.jpg346.7 KB · Views: 33

Avion III.jpg346.7 KB · Views: 33