hesham said:

I ran the web page above, which is in Russian through the Google translator. Then I cleaned it up using my best judgement to make it more flowing in English. I believe it's correct but I can't be 100% sure as I do not know Russian. The first half of the page is about the Ginga. Below is the 2nd half of the writeup, where it talks about the Tenga project.

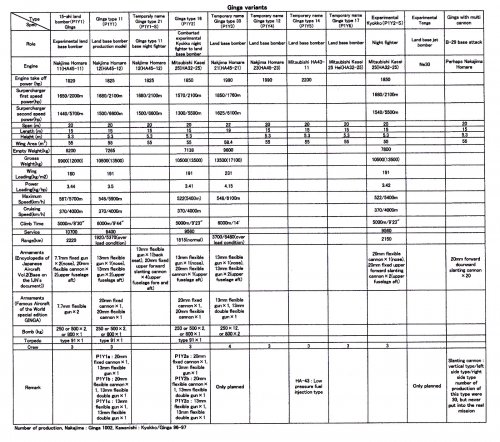

====

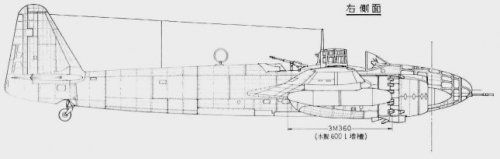

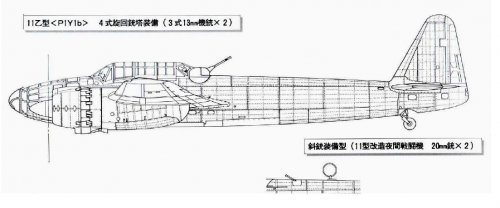

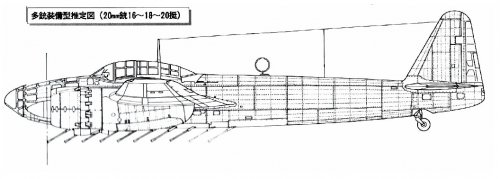

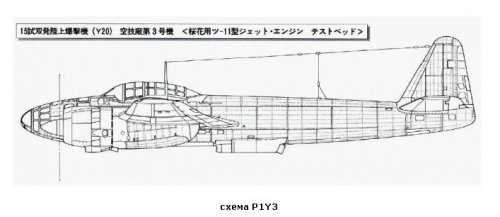

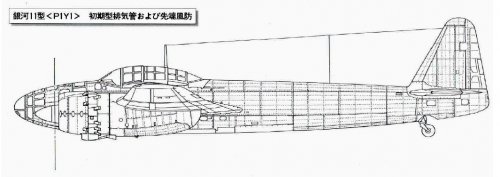

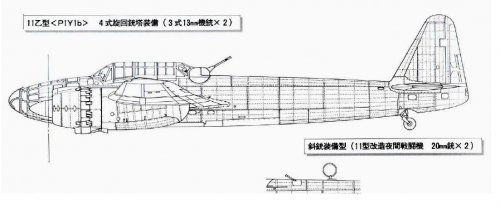

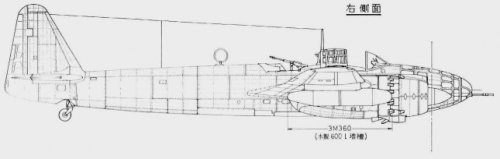

Ginga was developed in several versions, and there were plans to use the bomber as a carrier aircraft for special attack missions using the Ohka Model 21 and Ohka Model 22. The company also build a night fighter version, the P1Y2-S, which was produced for IJN in 1944, under the designation Kyokko (极光 - dawn ). Kyokko was equipped with 1,850 hp Mitsubishi Kasei 25a radial engines, as the scale of production of Ginga's original Homare 12 engine could not meet the demand. Armament included two Type 99 Model-2 20 mm cannon obliquely angled forward and upward, and the nose guns were removed. Test flights were held in July 1944. The first flight showed that the high altitude characteristics of Kyokko where it would engage the Boeing B- 29 were not satisfactory. This discovery was so disappointing that the oblique guns were removed and the Kyokko was returned to the interceptor role as Ginga Model 16 (P1Y2). Nakajima also built a similar version as the night fighter P1Y1-S Byakko (白 光 - White Light). Byakko performed a little better than Kyokko, but also did not enter service. Other modifications and modernization projects included the replacement of engines with the Homare 23, the Kasei 25c and the Mitsubishi MK9A, as well as the idea of an assault option with sixteen forward and downward firing 20 mm cannons, as well as the use of steel and wood in the aircraft structure. The most interesting version was the P1Y3 Model 33. This version was to be built from the ground up as a Ohka carrier and had to have a special bomb bay to accommodate Ohka Model 21 or 22, and included an increased wingspan and fuselage length. P1Y3 did not go beyond the drawing board.

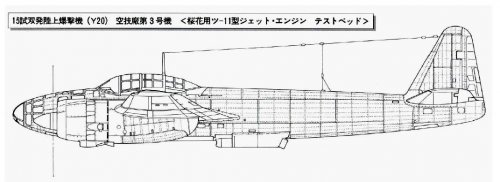

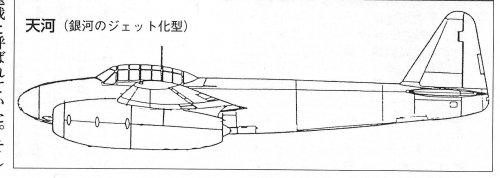

The good flight characteristics of the Ginga easily explain why there was an interest in modifying the plane for turbojet propulsion. The Tenga concept was certainly real, but other than the name and the main intention of replacing the radial engines with turbojets nothing more is known. Thus it is necessary to consider other projects in order to make assumptions about what challenges would be encountered when creating a flying example of the Tenga.

The first thing to consider is that the only turbojet used in the production of the Nakajima Kitsuka was the Kugisho Ne 20. If installed under the wing of the Tenga these could not provide this plane with a sufficient thrust. One Ne 20 has a static thrust of 487 kg, a couple of these engines could accelerate the Kitsuka to a speed of 623 km/hr, which was not particularly fast compared to conventional high-speed piston aircraft. Kitsuka was a light aircraft and, therefore the heavier Tenga, using two Ne 20's, would be an unlikely possibility.

It was necessary to make some of the planned improvements to Ne 20 closer to reality and thus be able to provide an adequate Tenga power plant. It was expected that Ne 30 turbojet engine would develop a thrust of 850 kg (better than the German BMW 003 turbojet engine's 800 kg), while the Ishikawajima Ne 130 was designed to create a static thrust of 900 kg, comparable to the thrust of the Junkers Jumo 004. According to calculations the Nakajima Ne 230 [Note: some sources say the Ne 230 was Hitachi instead of Nakajima - Windswords] and the Mitsubishi Ne 330 could develop 885 kg and 1300 kg of static thrust, respectively.

The improved Ne 30 would be the original engine for installation in the Tenga, if they were available. For comparison, the German jet bomber Arado Ar 234B used two Jumo 004 engines. The size of Ar 234B was similar to P1Y1, the noticeable differences between the German and Japanese machines were the smaller wingspan and high mounted wing, and the weight with a full load was lighter by 680 kg. Accordingly, two Jumo 004 engine allowed Ar 234B to reach speeds of 742 km/hr. Of course, installing two Ne 30 engines on a P1Y1 airframe would not provide such a speed, but it would be a logical starting point. It is possible that to improve take-off performance of the Tenga rocket boosters could be installed. It is also clear that the Ne 130 would be a better choice, giving a marked improvement in speed. The problems associated with the development of Ne 30 engines, are cited as reasons for cancellation of the Tenga. Indeed the Ne 30 was an offshoot of the Ne 12, whose development ceased, being surpassed by developments of the Ne 20, Ne 130, Ne 230 and 330.

But could the original Ginga aircraft, which used radial engines, have successfully been replaced with the installation of jet engines? This could be ispolzovaon [?] when trying to improve the design of Tenga. Even changing from radial to turbojet engines would require fairly substantial adjustments of the wing, but, a redesign of the wing for turbojet engines is an easier task than the redesign of the entire aircraft.

However, if we consider the history of military aviation, it will be difficult to find a regular bomber, who piston engines were replaces with turbojets with only a simple change of the power plant and redesigned wing. For example, even among the dozens of projects made by the German jet bombers, alteration piston bombers to turbojets were accompanied by a significant change, if not a complete redesign. One such example was the Messerschmitt Me 264, which during the test flight was equipped with four Jumo 9-211 radial engines. However, the proposed version with four turbojet engines bore little resemblance to the original design.

Perhaps the only noticeable alteration of an existing airframe from propeller to turbojet was the Russian Tupolev Tu-12, which was the successor of one of the most successful Soviet light bombers - the Tu-2. The Tu-2 was built from 1941 to 1948. TU-2 featured high speed, excellent maneuverability, was heavily armed and had a respectable bomb load. When Tupolev responded to the demand of creating a jet bomber, he took the TU- 2 as the basis for his Tu- 12. He used the fuselage, wing and tail of the Tu-2 and adapted them to suit the installation of two Rolls-Royce Nene-1 turbojet engines. Although one can see in the Tu-12 the features of its predecessor, the Tu-2 , it still required total redesign of aircraft to fit the new engines and features, all of this does not seem like a simple replacement of the radial engines with turbojets. Design of the Tu-12 began in 1946, and its first flight took place in June 1947.

It can be concluded that in the original version of the Tenga the designers tried to use as much as possible the structural elements of the Ginga, which had proven flight characteristics. This would reduce development time, as the need for such bombers was extremely urgent. It would also serve as a starting point for aerodynamic testing. However, one can count on one hand the number of bomber converted from piston to turbojet. Most of the jet bombers were developed from the ground up instead of adapting existing aircraft. Tenga designers would have come to a similar conclusion, if they were able to continue their work. If so, the final draft of the Tenga and the prototype may have had little in common with the Ginga with whom it shared its origin.