blockhaj

Swedish "want to be" aviation specialist

- Joined

- 9 February 2017

- Messages

- 389

- Reaction score

- 462

This post might get removed but i couldn't find any rules against pre-historic ships so why not.

This is a thread dedicated to Viking Age ironclads. Viking military ships, so called longships, were clinker-built made of wood and often as large as possible. A number of Viking Age stories tell of such ships being clad in iron plating. This was not common but appears to not be a foreign concept in the scripts.

The most described Viking ironclad can be found in Old Norse stories retelling the Battle of Svolder, a huge Viking naval battle around 1000 AD (kinda cool battle, look it up). In this battle, a perculiar ship is mentioned, Earl Erik's Járnbarðinn (The Iron Bard). It is described as a barða or járnbarða (iron-bard), indicating a specific type of ship. The saga Fagrskinna says it was the largets ship (of the battle), indicating bigger than the described ship Long Serpent with 34 rowing benches, meaning that Eriks barda might have been 40-50 meters long (compared to the largest longship today of 35 meters).

The saga Heimskringla gives more detail:

These Old Norse texts are all poetically written (initially based on so called Scaldic Poetry), meaning that objects, terms and the like, often get described using other words as per poetry. No one really knows what barda and bard (border/edge) actually mean in this story. Old Norse "bard" is an extrememy broad term, found today in for example the name Svalbard (Cold Edge) and halberd (from bard meaning axe). With that said, i think i have found a runestone carving which fits in with this described ship, what is believed to be Naglfar on the Tullstorp Runestone.

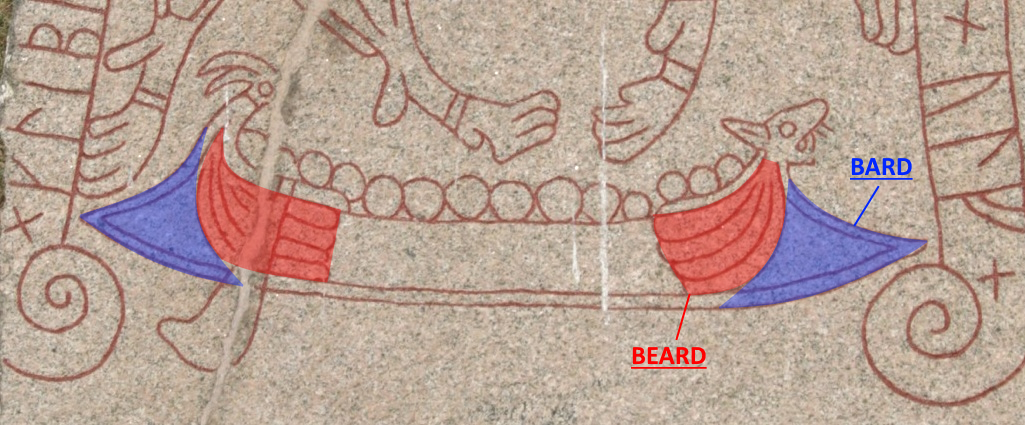

This ship carving differs greatly from other ship carvings, most notably by having protruding stems like the front of a galley or trireme, but also, above it, some type of coverig along the strakes at each end of the ship. Lets assume bard in the story simply refers to edge, as per these angular protruding stems, and beard referring to these strake covers, then the description sort of make sense (although the carving lacks a visible ram). Barda, a derivation of bard, makes sense as a name for this type of ship, as it features characteristic "edges". Its also a possibility that the entire protrusion in the carving might actually be the "iron beam" itself (although maybe slightly exaggerated), with Old Norse "spǫng" actually meaning protrusion here, as in: "a beneath iron protrusion, thick (tall) and wide as the bard (the stem). Although, now when i think about it, spǫng doesnt really set well with that meaning.

Some other connections of note, Naglfar is supposed to be a ginormous combat ship for the battle at the end of the world, so a carving of it makes sense to be a monstrous ironclad combat ship. Here is a link for those who want more details on why its supposedly Naglfar being depicted on the stone: https://k-blogg.se/2016/10/02/nar-fenrir-fick-farg/

Addition: 2023-12-20

Here is a snippet from Þorsteins saga Víkingssonar:

Addition: 2023-12-25

Here is a snippet from Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar

Same ship type found on the Ledberg stone of the same period (ca 1000 AD).

This is a thread dedicated to Viking Age ironclads. Viking military ships, so called longships, were clinker-built made of wood and often as large as possible. A number of Viking Age stories tell of such ships being clad in iron plating. This was not common but appears to not be a foreign concept in the scripts.

The most described Viking ironclad can be found in Old Norse stories retelling the Battle of Svolder, a huge Viking naval battle around 1000 AD (kinda cool battle, look it up). In this battle, a perculiar ship is mentioned, Earl Erik's Járnbarðinn (The Iron Bard). It is described as a barða or járnbarða (iron-bard), indicating a specific type of ship. The saga Fagrskinna says it was the largets ship (of the battle), indicating bigger than the described ship Long Serpent with 34 rowing benches, meaning that Eriks barda might have been 40-50 meters long (compared to the largest longship today of 35 meters).

The saga Heimskringla gives more detail:

Original Old Norse text: Eiríkr jarl hafði barða einn geysimikinn, er hann var vanr at hafa í víking; þar var skegg á ofanverðu barðinu hváru tveggja; en niðr frá járnspǫng þykk ok svá breið sem barðit ok tók alt í sjá ofan. |

Open translation: Earl Eirik owned a mighty great barda which he was accustomed to take on his viking expeditions; it had beard (assumed to be iron plating) above each of both bards (assumed to be the stems); beneath, an iron beam (a ram) protruded, thick and wide as the bard (the stem), which took all at sea above. |

These Old Norse texts are all poetically written (initially based on so called Scaldic Poetry), meaning that objects, terms and the like, often get described using other words as per poetry. No one really knows what barda and bard (border/edge) actually mean in this story. Old Norse "bard" is an extrememy broad term, found today in for example the name Svalbard (Cold Edge) and halberd (from bard meaning axe). With that said, i think i have found a runestone carving which fits in with this described ship, what is believed to be Naglfar on the Tullstorp Runestone.

This ship carving differs greatly from other ship carvings, most notably by having protruding stems like the front of a galley or trireme, but also, above it, some type of coverig along the strakes at each end of the ship. Lets assume bard in the story simply refers to edge, as per these angular protruding stems, and beard referring to these strake covers, then the description sort of make sense (although the carving lacks a visible ram). Barda, a derivation of bard, makes sense as a name for this type of ship, as it features characteristic "edges". Its also a possibility that the entire protrusion in the carving might actually be the "iron beam" itself (although maybe slightly exaggerated), with Old Norse "spǫng" actually meaning protrusion here, as in: "a beneath iron protrusion, thick (tall) and wide as the bard (the stem). Although, now when i think about it, spǫng doesnt really set well with that meaning.

Some other connections of note, Naglfar is supposed to be a ginormous combat ship for the battle at the end of the world, so a carving of it makes sense to be a monstrous ironclad combat ship. Here is a link for those who want more details on why its supposedly Naglfar being depicted on the stone: https://k-blogg.se/2016/10/02/nar-fenrir-fick-farg/

Addition: 2023-12-20

Here is a snippet from Þorsteins saga Víkingssonar:

Original Old Norse text: Hálfdán átti dreka stóran, ok var hann kallaðr Járnbarði, hann var allr járni varðr fyrir ofan sjó, borðhár ok hinn bezti gripr |

Open translation: Halvdan had a big dragon (a longship), and which he called Járnbarði (The Iron Barde), he was all iron wrapped afore above sea, freeboard-high and the best possession |

Addition: 2023-12-25

Here is a snippet from Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar

Original Old Norse text: (note the erronous spelling in my copy) Oc siðan býsc Eríkr jarl med lið sitt; hann hafði þat skip er callat var Jarnbarðiɴ. þat var mikit skip oc akaflega harðgert. stafniɴ huorr tueggi þakiðr með miklu iarni. oc huossum eggia broddum |

Original Old Norse text: And then came Earl Erik with his lead; he had that ship which was called The Iron Barde. It was a large ship and very heavily covered (protected). The stem was twofold (on both sides) covered with much iron. and sharp edged spikes |

Same ship type found on the Ledberg stone of the same period (ca 1000 AD).

Last edited: