In the late 1970s, two companies, Chrysler and General Motors, had competing prototypes of the M-1. General Motors had a large and traditional diesel engine in the tank, and Chrysler, which had tried and failed to develop turbine engine technology for cars and trucks for the commercial market, wanted to recoup their costs and put a risky and complicated turbine engine in their tank. The Army was ready to give the contract to General Motors, but politics intervened. In 1987, the Washington Monthly laid out the scene around the all-important decision of what tank was to be chosen:

On a July afternoon ten years ago, Lt. Colonel George Mohrmann sat at his desk on Capital Hill awaiting a phone call. As head of the Army’s congressional liaison office, he was ready to deliver a stack of sealed letters to members of Congress announcing the winning contractor in the multi-billion dollar competition to build the Army’s M-1 tank.

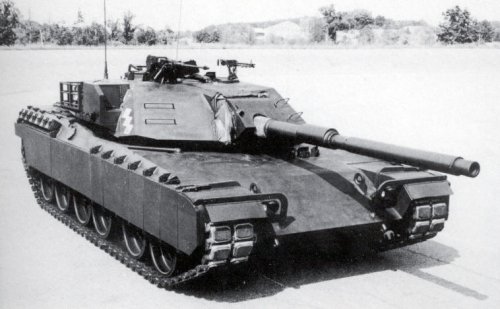

The two competing contractors, Chrysler and General Motors, offered a clear choice. Chrysler had built its tank around a radically different and unproven tank engine, the turbine; GM had used a more conventional diesel engine. The two tanks had undergone months of head-to-head trials at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland.

GM had won.

The Army, it seemed, was not going to risk adding the M-1 to its growing list of overly sophisticated weapons that cost too much and don’t work. “We were sitting there poised to deliver [the envelopes],” Mohrmann recalls. “The decision [to select GM] had been made. We were just waiting for the Secretary of Defense to be briefed.”

The call, however, was surprising. The Pentagon told Mohrmann not to deliver the letters. The next day, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld ordered a whole new round of competition. A week later, Rumsfeld turned the M-1 tank program upside down. He mandated that the tank be redesigned to incorporate the turbine engine. Four months later the award-which promised to generate $20 billion in sales – went to Chrysler and the Army was on its way to getting a weapon suited more for a paved interstate than a battlefield.

… That isn’t another story about the Army’s incompetent bureaucracy. “You can blame the Army for a lot of things,” says Anthony Battista, a staff member of the House Armed Services Committee, “but not for the troubles of the M-1.” Rather, it’s a story of how outside factors can overwhelm military considerations in the Pentagon decision-making process, how narrow interests – in this case the ailing Chrysler Corporation and, by a strange twist, the U.S. Air Force – can outweigh the need for a reasonably-priced and effective military. The M-1 was never just a weapon; it was also a bail-out package.