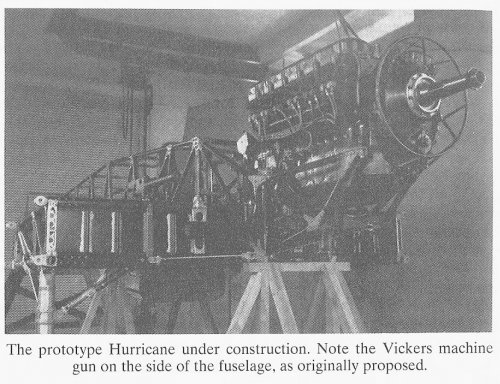

Robunos: The picture is of a Hurricane mock up with two fuselage mounted fixed forward firing 0.303s? Correct?

it's the actual Hurricane prototype, under construction. Armament was to have been four machine guns; this from

Putnam's 'Hawker', page 286 :-

"...a new specification, F.36/34, was drafted around the design as it stood in August, 1934...

The F.36/34 design was accepted and in February 1935...

manufacture of a prototype to have... an armament of four guns - a Vickers gun on each side

of the nose, and either a Browning or Vickers gun in each wing. Arguments in favour of a

heavier armament were, however, accepted and the contract was amended to provide for the

inclusion of...eight Browning machine guns."

Bailey: The picture shows the Dolphin's Lewis gun's at different angles - does this mean that only one gun could be used at a time (in which case it is properly a two-gun armament with two additional one gun stations)? Or were they fitted with a crossbar to link the two guns?

If I may...

From Putnam's 'Sopwith', page 208 :-

"Details of how the Lewis guns were to be installed...and to limit the training (aiming) of these guns a three position

ratchet was the approved fitting.The extent to which two Lewis guns were actually fitted as well as the two 'built-in'

Vickers, remains unclear; although a single Lewis was far more common in the field, a familiar picture of ...C3786...

with both Lewis guns fitted, while others have their Vickers guns only..."

The revised Sopwith Salamander "trench fighter" was to have three guns. This was a pusher aeroplane.

The Sopwith Salamander was *never* a pusher design. I think you are confusing the Salamander with the Vickers FB.26

Vampire, which *was* a pusher, and *was* tested with the Eeman triple gun mounting.

The Salamander, AFAIK a development of the snipe, had two guns angled downwards,

firing through the armoured nose section and a single forward gun.

The Salamander was originally intended to have this armament arrangement, but following evaluation of the similarly armed

Sopwith TF.1 Camel, it was decided that this armament scheme was unworkable, and the Salamander's guns were re-arranged

as two forward firing Vickers guns. See 'the First British Armoured Brigade', Air International, March 1979, pp.149-153, and

April 1979, pp.182-190, and pp.199-200.

The Salamander was a development of the Snipe, although with a strengthened structure to cope with the added weight of the

armour. It was fortunate that the war ended when it did, for in December 1918, it was discovered that a large number of the

Salamanders thus far built had been fitted in error with Snipe centre-sections, which rendered the aircraft dangerously weak.

Fortunately, they could be grounded without any problems...

cheers,

Robin.