- Joined

- 19 October 2012

- Messages

- 1,953

- Reaction score

- 1,842

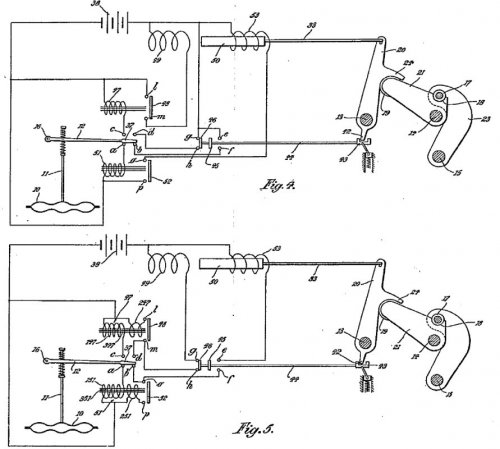

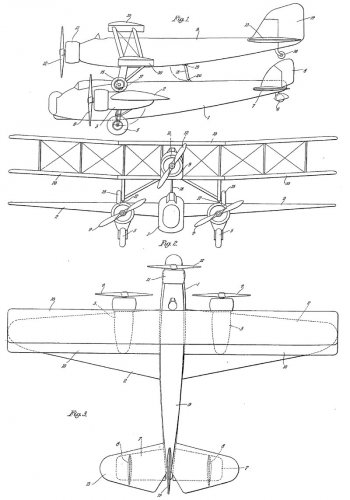

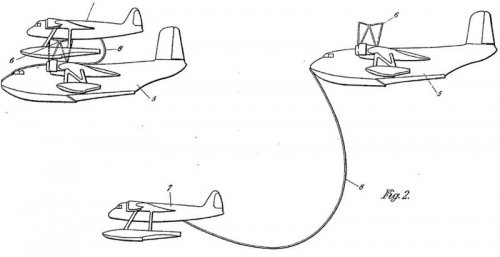

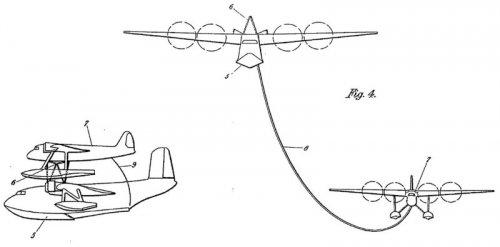

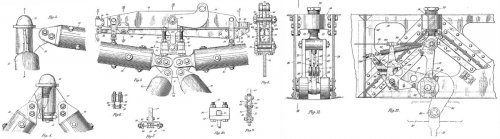

Major Robert Mayo, aviation consultant and General Manager (Technical) at Imperial Airways Ltd (IAL) conceived the idea for a composite aircraft, the lower component serving to enable take-off of the heavily-loaded upper component, which was carried on its back. The concept, and the operation of the key attachment and release mechanism, was patented in 1932 with follow-up patents in 1933, 34 and 36.

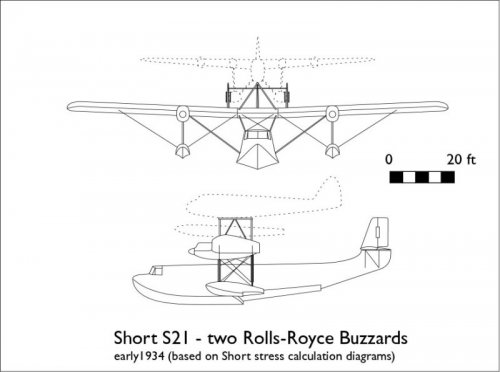

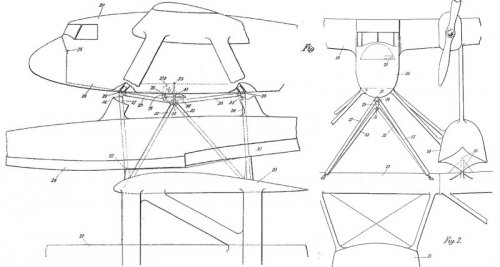

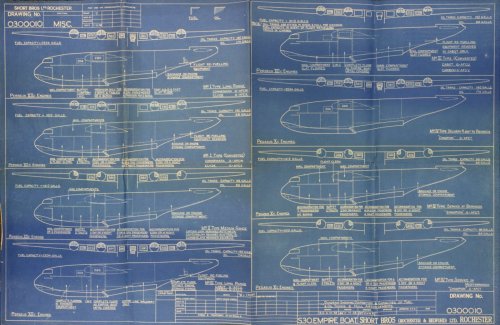

Short Bros were invited to tender for both aircraft in 1933 (there does not appear to have been a competitive tendering process) and they carried out some preliminary tests and calculations which were presented to Mayo, IAL and the Air Ministry. IAL and the Ministry agreed to finance the construction of aircraft, for which they drew up spec. 13/33. Shorts submitted their final proposal in September 1934 and were authorised to proceed.

The two aircraft, Maia, a seaplane, as the lower component and Mercury, a float plane, as the upper component were flown in 1937 and achieved the first separation in early 1938. This and subsequent tests were all successful and proved the concept.

Mayo, naturally, was keen to sell the composite concept for other applications and came up with a variety of ideas, both commercial and military.

After Maia/Mercury had proven the viability of the concept Short were asked to tender for a landplane upper component, basically a landplane version of Mercury, for use as a trans-Atlantic or Empire mailplane. Three and four-engined options were tendered; either to be carried by one of IAL’s Armstrong-Whitworth Ensigns re-engined with Armstrong-Siddeley Deerhounds. However by this point IAL were losing interest in the concept and the Deerhound was proving problematic; the flight test aircraft was lost in a crash.

In 1939 Mayo made tentative suggestions for two further mailplanes; a small one to be carried by a DC3 and a medium size one to be carried by a DC4. Nothing came of this.

On the military front Mayo saw the composite as an ideal way to launch a small, high-speed, long-range, bomber. In 1935 Gloster were asked to submit a design for a two-man bomber with a range of 2000 miles carrying 2000lb of bombs. No lower component was specified by Mayo. In Gloster’s tender it is implied, but not stated, that Mayo had specified a single engine. Gloster’s calculations showed that the idea was flawed, the performance of the heavily laden bomber required separation at high speed and high altitude, both considerably above those to be assessed by Maia/Mercury. The project was dropped. Mayo, however, was not deterred and continued to push the concept in 1936 and again in 1939, suggesting a performance by the bomber far in excess of that estimated by Gloster, but without explanation. The lower component would be an Armstrong Whitworth Whitley MkIV.

In 1940 he tried again, but now focussed on reconnaissance applications and suggested a 25,000 lb aircraft with two or three-engines, total of around 1700 hp. This, too, fell on deaf ears.

But then things took a turn for the better. In late 1940 Air Commodore Marix, of Coastal Command, asked whether it would be feasible to carry a Supermarine Spitfire on the back of a Whitley. The idea was to patrol up to 500 miles into the North Atlantic and to launch the Spitfire against prowling anti-shipping aircraft. The Spifire could then fly back to land after the engagement. Mayo responded in the positive. The project was then redefined to be a Hawker Hurricane carried by a Consolidated Liberator, and this was given sanction to proceed at the end of 1940. Hawker produced drawings for the modification required for the Hurricane; mounting points, control locks, enlarged oil tanks etc. while Rolls-Royce collaborated on the system to enable the Hurricane to draw fuel from the Liberator. Shorts in Belfast commenced work on the cradle and other parts required for fitment on the Liberator. All seemed to be proceeding well. In early April Hawker had nearly completed all the new parts and a Hurricane had been selected for modification and would arrive shortly. The modifications were expected to take one week. However there was no sign of the Liberator and Shorts were unable to complete their work until it arrived when they would be able to make a detailed assessment of its structure. The Air Ministry, or Ministry of Aircraft Production, for reasons unknown, pulled the plug, leaving Mayo to send one last desperate letter hoping to get the decision reversed. The project was dead.

Nothing more was heard of Mayo’s Composite Aircraft concept.

Short Bros were invited to tender for both aircraft in 1933 (there does not appear to have been a competitive tendering process) and they carried out some preliminary tests and calculations which were presented to Mayo, IAL and the Air Ministry. IAL and the Ministry agreed to finance the construction of aircraft, for which they drew up spec. 13/33. Shorts submitted their final proposal in September 1934 and were authorised to proceed.

The two aircraft, Maia, a seaplane, as the lower component and Mercury, a float plane, as the upper component were flown in 1937 and achieved the first separation in early 1938. This and subsequent tests were all successful and proved the concept.

Mayo, naturally, was keen to sell the composite concept for other applications and came up with a variety of ideas, both commercial and military.

After Maia/Mercury had proven the viability of the concept Short were asked to tender for a landplane upper component, basically a landplane version of Mercury, for use as a trans-Atlantic or Empire mailplane. Three and four-engined options were tendered; either to be carried by one of IAL’s Armstrong-Whitworth Ensigns re-engined with Armstrong-Siddeley Deerhounds. However by this point IAL were losing interest in the concept and the Deerhound was proving problematic; the flight test aircraft was lost in a crash.

In 1939 Mayo made tentative suggestions for two further mailplanes; a small one to be carried by a DC3 and a medium size one to be carried by a DC4. Nothing came of this.

On the military front Mayo saw the composite as an ideal way to launch a small, high-speed, long-range, bomber. In 1935 Gloster were asked to submit a design for a two-man bomber with a range of 2000 miles carrying 2000lb of bombs. No lower component was specified by Mayo. In Gloster’s tender it is implied, but not stated, that Mayo had specified a single engine. Gloster’s calculations showed that the idea was flawed, the performance of the heavily laden bomber required separation at high speed and high altitude, both considerably above those to be assessed by Maia/Mercury. The project was dropped. Mayo, however, was not deterred and continued to push the concept in 1936 and again in 1939, suggesting a performance by the bomber far in excess of that estimated by Gloster, but without explanation. The lower component would be an Armstrong Whitworth Whitley MkIV.

In 1940 he tried again, but now focussed on reconnaissance applications and suggested a 25,000 lb aircraft with two or three-engines, total of around 1700 hp. This, too, fell on deaf ears.

But then things took a turn for the better. In late 1940 Air Commodore Marix, of Coastal Command, asked whether it would be feasible to carry a Supermarine Spitfire on the back of a Whitley. The idea was to patrol up to 500 miles into the North Atlantic and to launch the Spitfire against prowling anti-shipping aircraft. The Spifire could then fly back to land after the engagement. Mayo responded in the positive. The project was then redefined to be a Hawker Hurricane carried by a Consolidated Liberator, and this was given sanction to proceed at the end of 1940. Hawker produced drawings for the modification required for the Hurricane; mounting points, control locks, enlarged oil tanks etc. while Rolls-Royce collaborated on the system to enable the Hurricane to draw fuel from the Liberator. Shorts in Belfast commenced work on the cradle and other parts required for fitment on the Liberator. All seemed to be proceeding well. In early April Hawker had nearly completed all the new parts and a Hurricane had been selected for modification and would arrive shortly. The modifications were expected to take one week. However there was no sign of the Liberator and Shorts were unable to complete their work until it arrived when they would be able to make a detailed assessment of its structure. The Air Ministry, or Ministry of Aircraft Production, for reasons unknown, pulled the plug, leaving Mayo to send one last desperate letter hoping to get the decision reversed. The project was dead.

Nothing more was heard of Mayo’s Composite Aircraft concept.