SPANGENBERG: []Then in '59 we started the Eagle/Missileer competition. We did the Eagle and then later the Missileer which was a forerunner of the TFX and of the F-14. The whole development series really started back in '55.

RAUSA: Was the Missileer an actual aircraft?

SPANGENBERG: The whole thing started with the threat projections being such that it was becoming very difficult to protect the fleet against Mach 2 raids coming in. You had to have something better than we had with F4/Sparrow capability aircraft. All the studies said you just couldn't get there in time to shoot down enough and the surface-to-air missiles just couldn't handle the degree of the threat either. It turned out that studies in the mid-fifties indicated that the state of the art in radar was such that we could do a long-range radar search type of thing and get it into an airplane. Took about a five foot dish to do it. This then led to probably the biggest study effort in the Op analysis field that at least the Navy had done up to that point on how best to do the fleet defense mission. That study was known as RAFAD and out of that came the determination that the only real way to do the job was with a CAP airplane and long-range missiles. It was far superior to trying to do the high speed intercept and so on. With the threat then being projected as Mach 2 kind of performance and launching missiles against you it was imperative that they get stopped or at least well thinned out by one hundred miles out or thereabouts.

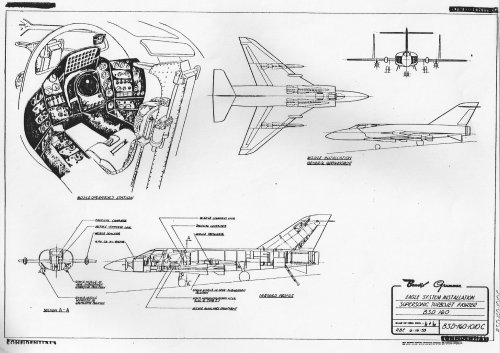

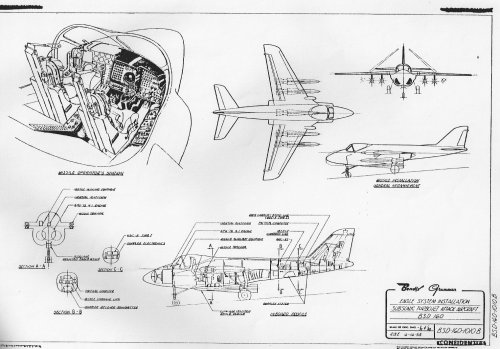

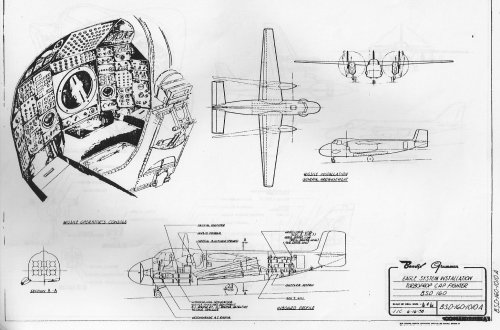

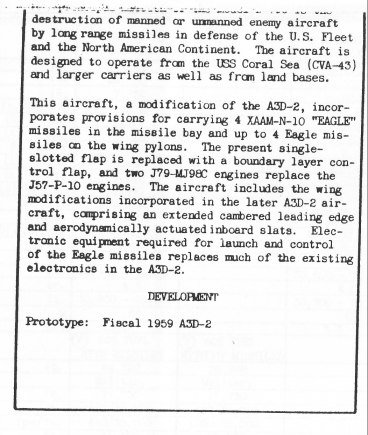

At the time we started on that the Air Force had gone the other way and started the XF-12 airplane which eventually became the SR-71, with Mach 3 kind of performance but using single shot missiles. That airplane as you know was a very large airplane, 100,000 pound category and very long, impossible to operate from a carrier unless we got much, much larger carriers. That option of going that way really wasn't open to us and also it was a very expensive way to do it. All those Op analysis studies said that we couldn't get there from here. So Navy sold to the Congress a program to do Eagle Missileer. Eagle was about a 100 mile missile with mid-course guidance and terminal homing. The missile itself weighed on the order of as I recall 1300 pounds a piece, something on that order. Then the fire control system was being done by Westinghouse. I just mentioned there was a five-foot dish. The Eagle missile and fire control system part of the program started a couple years before the airplane did and the TF-30 engine got started about that time in order to provide the engine and the missile system in time to match the airplane. Our habit in those days was to get the long lead items under way before you did the air frame because really the air frame has a shorter development time required. At the time of the Eagle competition, Grumman had won a whole batch of competitions. They had the E-2 going on, the Mohawk going on. They had won the A-6 competition. The Chief of the Bureau then was Adm. Bob Dixon and he told Grumman unofficially that he didn't think that they should win the next competition coming up. They were going to get overloaded. Unfortunately, Grumman was really on a roll there. They had done a reorganization, put good guys in charge of all the forward looking programs and had a good crew. Grumman ended up by foxing the Navy by not bidding as a prime but as a sub-contractor to Bendix. Bendix won the Eagle competition and Grumman was heavily involved in the effort.

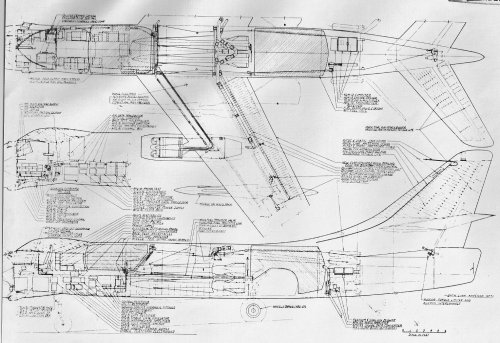

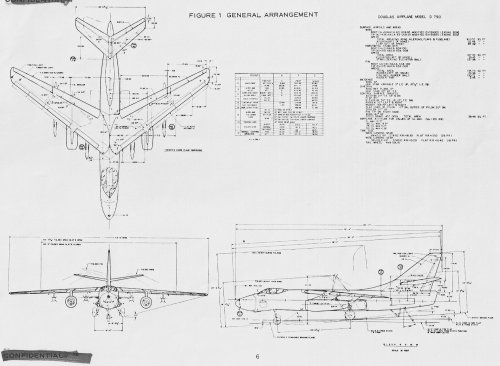

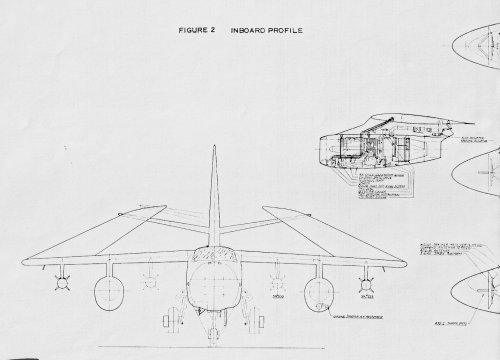

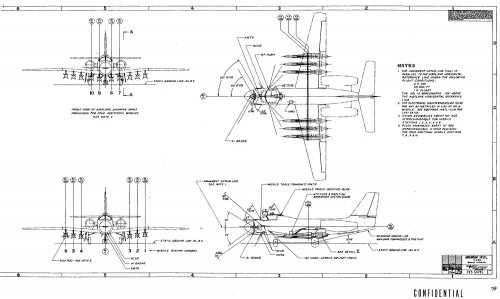

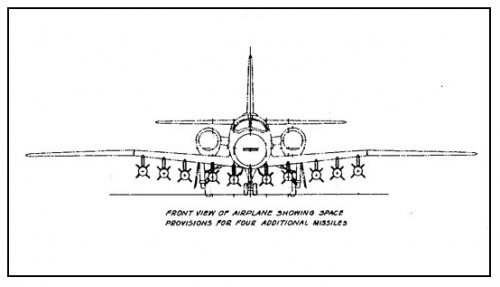

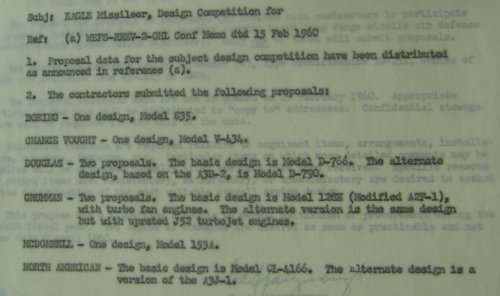

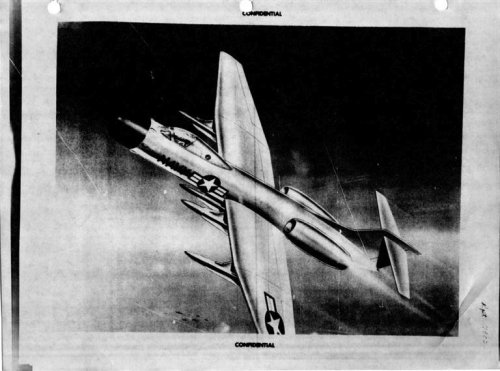

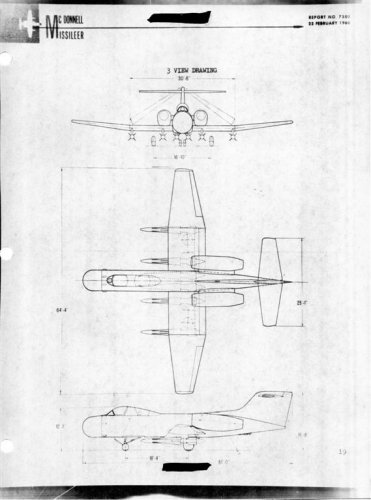

The Eagle program went along fairly well, well enough that the airplane part of it got started on schedule in 1959. That was a pretty tough competition. It was a controversial airplane in the sense it was such a low performance airplane. It was to be a subsonic airplane, two turbo fan engines, two place side by side and as I said with this five foot radar dish in the nose. The air frame part of the game was really not too difficult a technical job. It would have been obviously a lot easier than it would have been doing a supersonic type of airplane. That competition then ended with Douglas winning it with a very straightforward design with six missiles mounted on the wings, three on each side, externally. Straightforward airplane.

One of the interesting things out of the competition was a Vought entry which had predicted extremely low missile drag as mounted on their airplane based on wind tunnel tests. What it had amounted to in effect was that they ended up with positive interference drag. Usually you can take the drag of a pylon, the drag of a missile, put the two together and you add another hunk of drag to it for interference. In the case of Vought they were showing that the combination of a pylon and the missiles was less than the total of the two individual drags. Our aero guys didn't believe that and it became a big issue. If they had been right they would have been a more serious contender for getting the award than they were. With our performance estimate they were definitely in second place.

Subsequent to the award to Douglas, Vought turned all their drag data over to Douglas. This was not the first time that this type of thing had happened but it's worth mentioning that in these competitions that the losing contractors if they have something worthwhile in it will normally give it to their competitor in order to get a better plane for the fleet. It's worth mentioning because every once in a while there's a federal program or an OSD directive that we should do "technology transfer" or try to pick the best items out of each airplane and so on. It happens automatically if it's worth doing. Unfortunately with the Missileer, McNamara's arrival on the scene came along. The outgoing administration did not want to let a full development contract until the incoming administration approved the program. So we kept Douglas on a low level engineering effort probably under $1 million to do some preliminary engineering but then left the decision whether to go ahead in May to the incoming administration.

McNamara's crew, as you know, then said the Navy has a new airplane started, the Air Force has a new fighter started called TFX in the Air Force terminology. They're going to fight the same enemy, why don't they do it with one airplane? And the general impression that the working level guys had was the conversation must have been almost that casual, if they're going to fight the same enemy they can do it with one airplane. It later developed into a God awful mess. The whole TFX story has had books written about it. As a sidelight I guess I read three of the books and in no case did the authors of those books talk to me. Never. And most of them are wrong. All of them are wrong. Parts of the books are correct but the inferences drawn as to why we did things and why we didn't do things are all wrong. The first one was supposed to be McNamara proving to the services that he could wear them down. The military was fighting civilian rule and that wasn't the case at all. The Air Force and Navy were really only doing a technical job that McNamara's crew was screwing up and it was just awful.

RAUSA: And this hadn't happen before where you had the DOD staff intermingling into the development of an aircraft?

SPANGENBERG: No. Up to that time in my understanding, in my experience what happened, the OSD staff might question you on something but they'd accept the reasoning or the technical input from the services. McNamara's crew just didn't believe us and they had a bunch of honest to God incompetents. But the outcome of that mess was the McNamara group cancelled the airplane, the Eagle continued into early 1960 and it finally got cancelled I think in May of 1960. So thus ended the Eagle Missileer concept but it set the stage then for the things that came later, the TFX.