- Joined

- 12 November 2021

- Messages

- 43

- Reaction score

- 84

The successor to the X-15 was - a winged satellite? In the mid-1950s, NACA was pushing the boundaries of hypersonic flight. After the X-15, the Air Force's Project HYWARDS aimed to design a Mach 12 successor. Visionary engineer John Becker at NACA Langley proposed an even more ambitious goal: a hypersonic glider reaching Mach 18.

Becker's study group at Langley initially targeted Mach 15 but soon realized Mach 18 was more suitable, representing the peak heating environment for boost-gliders.

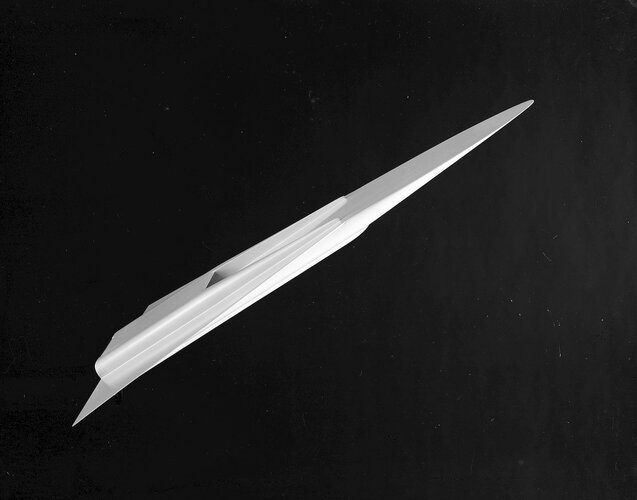

Key innovations included a delta wing with a flat bottom surface, which minimized heating area and reduced the need for coolant and thermal protection. The fuselage was positioned to cross the cooler, shielded region atop the wing, further reducing thermal protection needs. The design optimized wing loading and skin temperature to balance structural weight and thermal protection. Operating at a high angle of attack during reentry, the glider had enhanced aerodynamic efficiency and reduced the need for surface coolant.

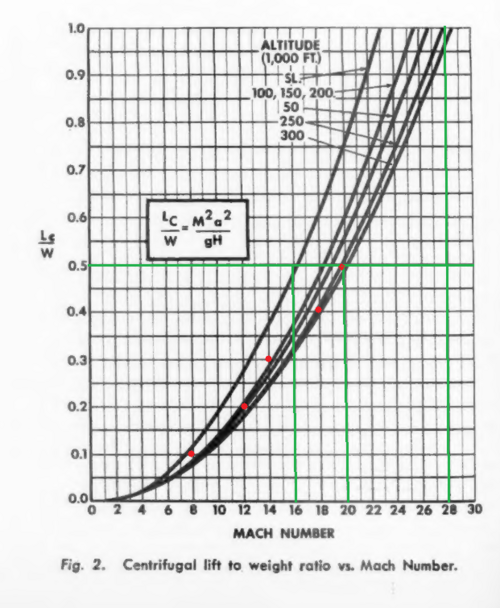

Becker's design utilized centrifugal lift at near-orbital speeds, carrying the glider's weight mainly by centrifugal force. This reduced the importance of the aerodynamic lift-drag (L/D) ratio, allowing a focus on reducing heating and structural weight: "at the near-orbital launch speed required for "once-around" or global range, the group found theoretically that the glider weight would be carried initially almost entirely by the centrifugal force produced by the launch. Considering this, the group perceived that aerodynamic L/D lost most of its importance. Thus, for global range, the study showed that a certain glider design with low L/D would require only about three percent higher launch velocity than a design with L/D four times higher."

A technical debate with Ames Laboratory, which focused on maximizing L/D ratio, led to a compromise. Langley's smaller wing design with a high-lift, high-drag trajectory increased the glider's range from 4,700 to 5,600 nautical miles.

Becker's work highlighted the importance of balancing aerodynamic efficiency with thermal protection. In 1957, as Sputnik launched, NACA held its last major conference on high-speed aerodynamics. Cones, lifting bodies, and gliders became differentiated opinions. Becker's paper, "Preliminary Studies of Manned Satellites, Winged Configurations", dissenting from the consensus favoring ballistic projectiles, presented a vision for a winged, hypersonic vehicle capable of precise reentry and landing, influencing future aerospace innovations. "According to Becker, this paper...created more industry reaction- "almost all of it favorable" -than any other he had written."

Were it not for Sputnik and consensus toward a ballistic projectile, "Becker today believes, "the first U.S. manned satellite might well have been a [one-man] landable winged vehicle," a miniature (3000-pound) version of the later (180,000-pound) space shuttle."

National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), "Engineer in Charge," Detailed report on Project HYWARDS, including technical details on centrifugal lift, aerodynamic heating, collaborative efforts between NACA Langley and Ames Laboratories, and John V. Becker's contributions. Published in 1986, all of the information contained herein has been in the public domain for 38 years.

Available at:

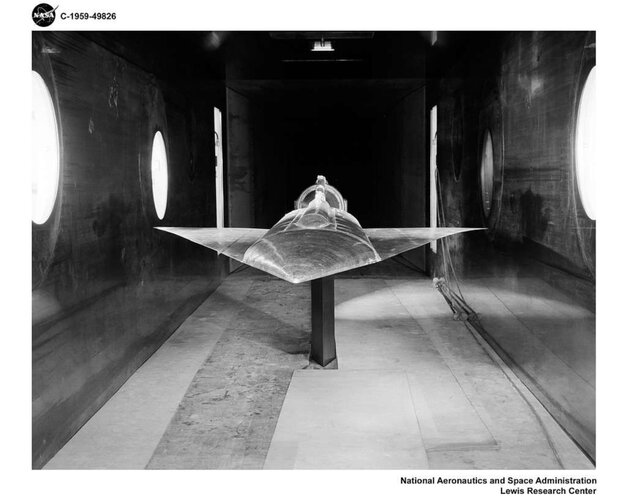

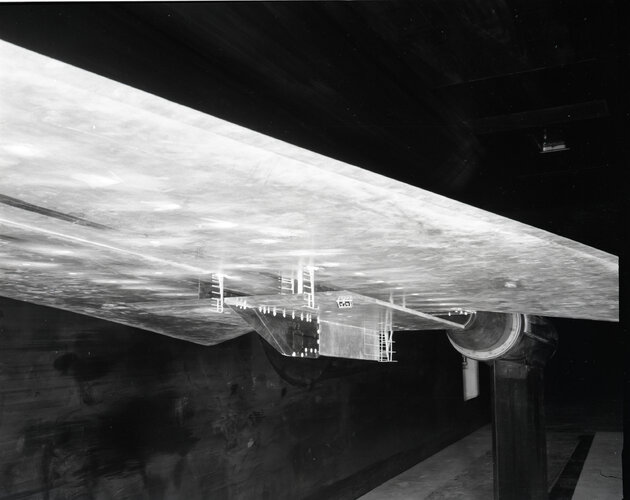

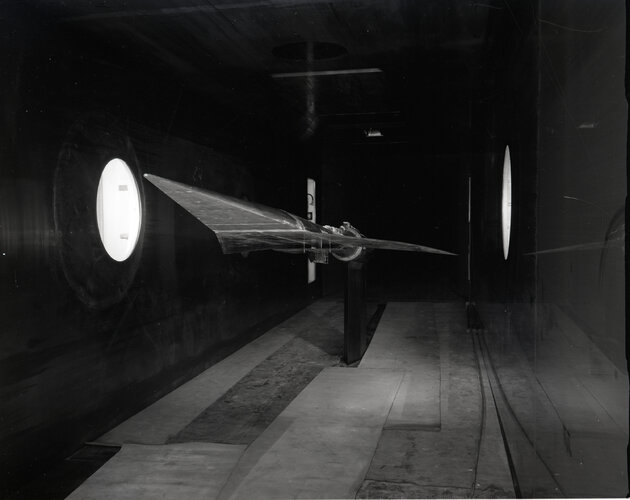

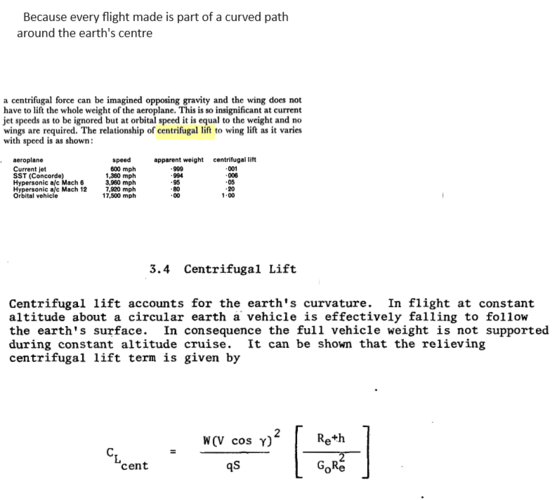

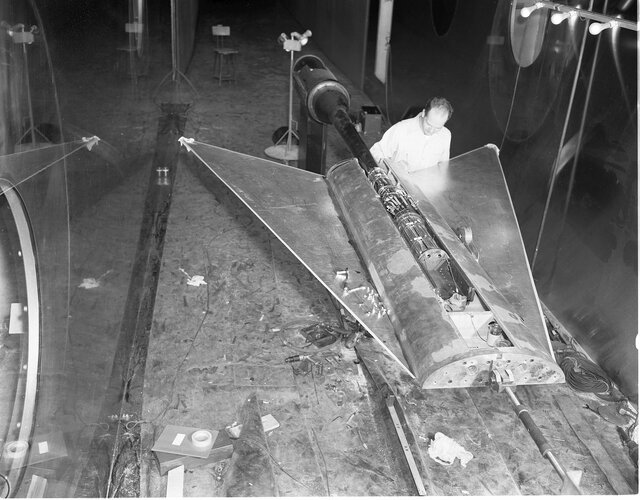

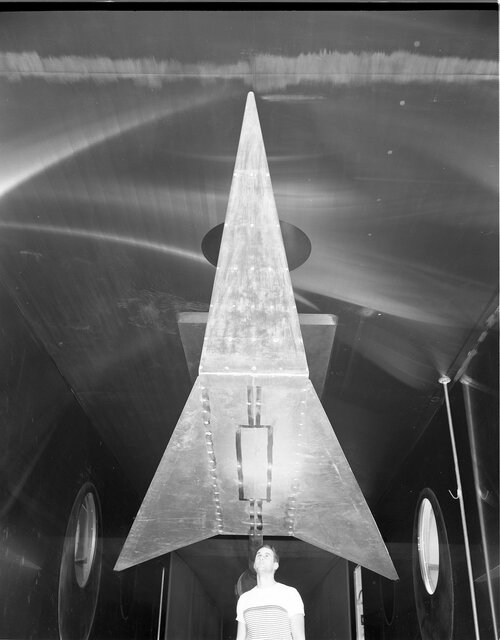

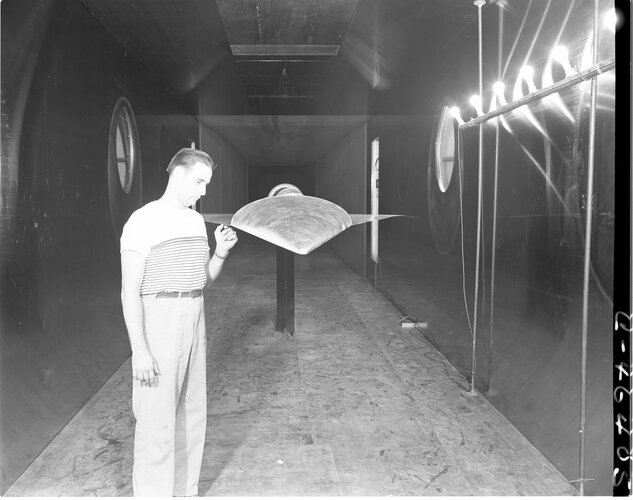

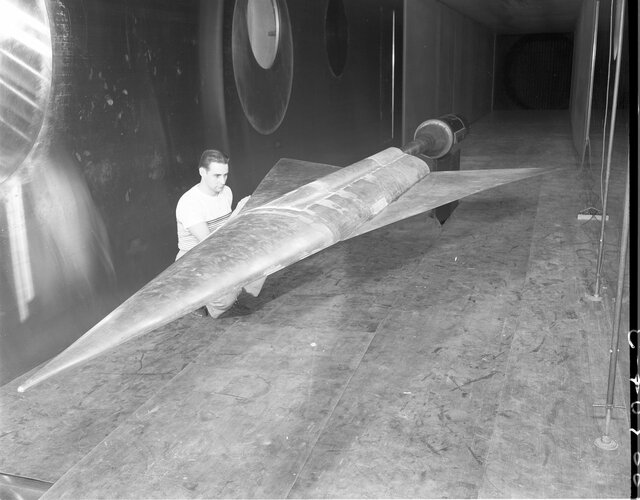

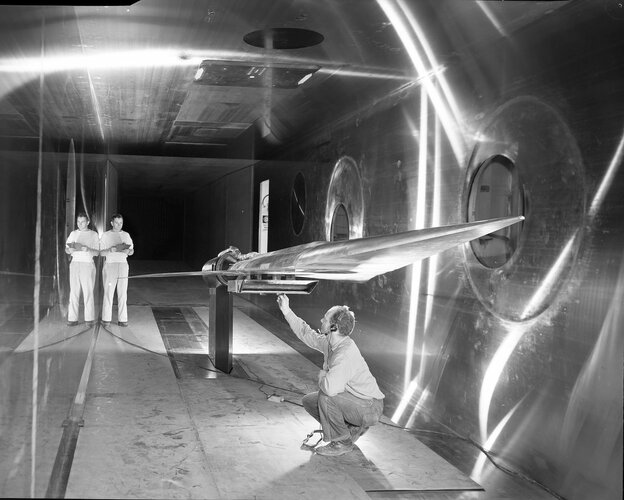

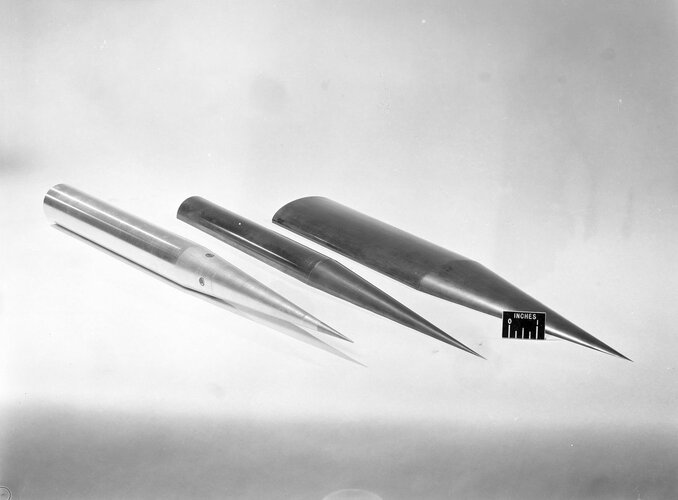

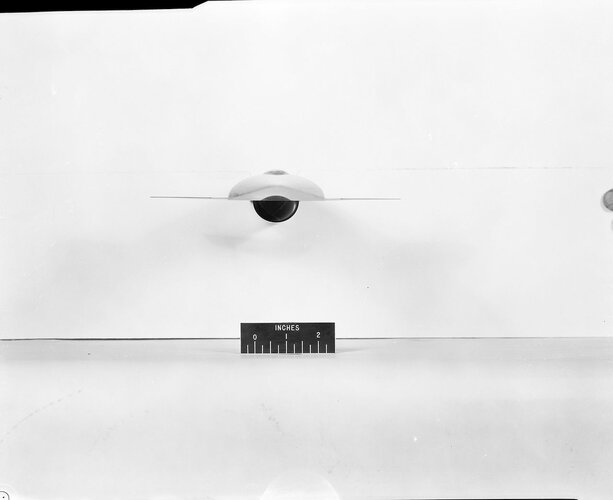

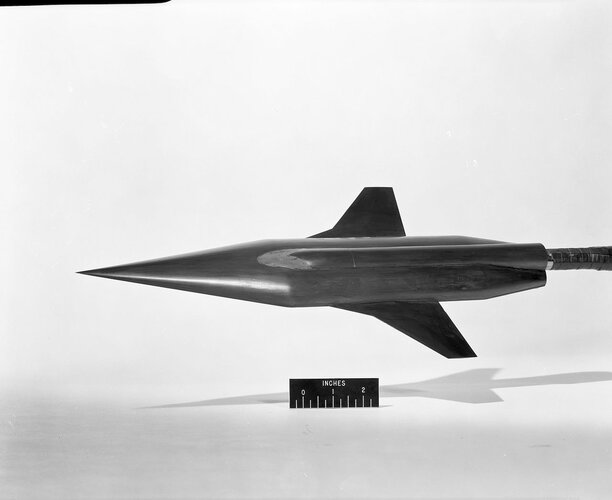

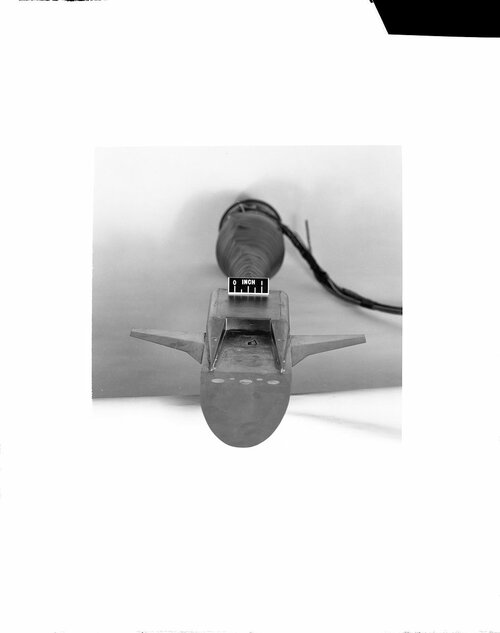

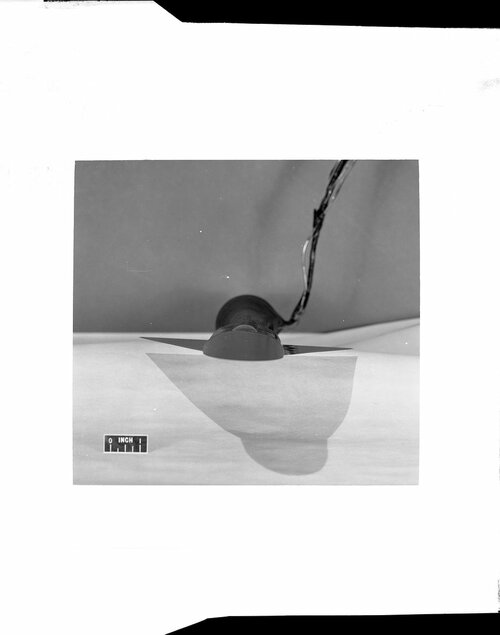

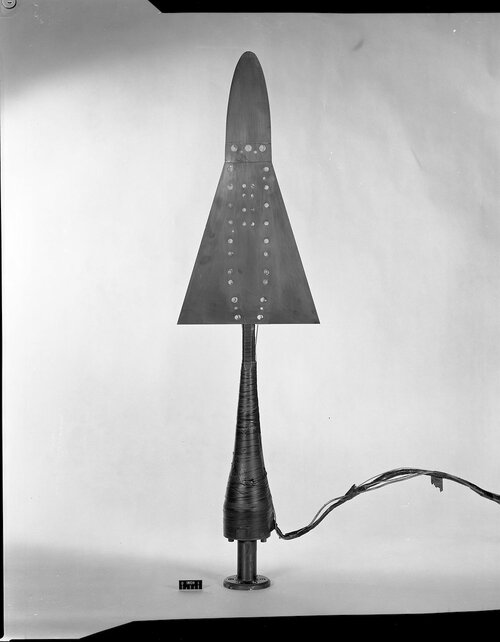

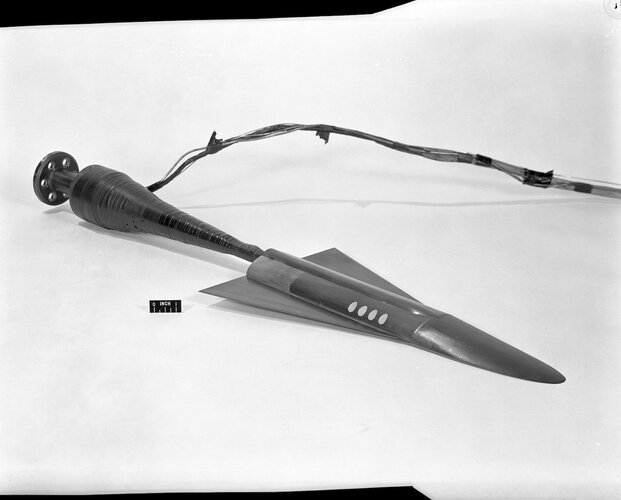

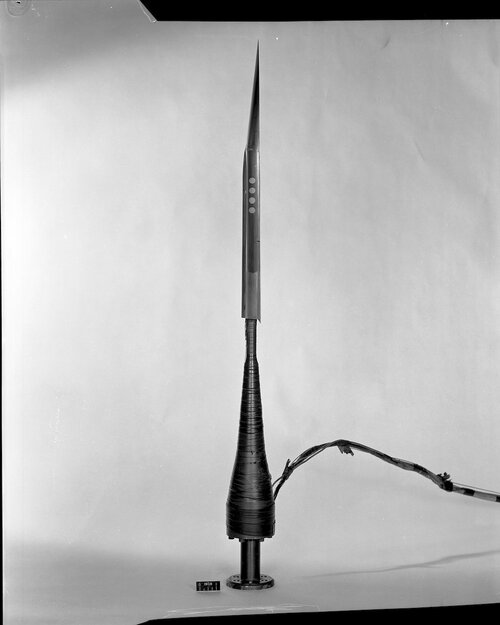

The image used in this document is sourced from the NACA archives, depicting early hypersonic glider testing in a wind tunnel. Available at: https://picryl.com/media/high-lift-...he-10x10-foot-wind-tunnel-test-section-6eaaae.

Becker's study group at Langley initially targeted Mach 15 but soon realized Mach 18 was more suitable, representing the peak heating environment for boost-gliders.

Key innovations included a delta wing with a flat bottom surface, which minimized heating area and reduced the need for coolant and thermal protection. The fuselage was positioned to cross the cooler, shielded region atop the wing, further reducing thermal protection needs. The design optimized wing loading and skin temperature to balance structural weight and thermal protection. Operating at a high angle of attack during reentry, the glider had enhanced aerodynamic efficiency and reduced the need for surface coolant.

Becker's design utilized centrifugal lift at near-orbital speeds, carrying the glider's weight mainly by centrifugal force. This reduced the importance of the aerodynamic lift-drag (L/D) ratio, allowing a focus on reducing heating and structural weight: "at the near-orbital launch speed required for "once-around" or global range, the group found theoretically that the glider weight would be carried initially almost entirely by the centrifugal force produced by the launch. Considering this, the group perceived that aerodynamic L/D lost most of its importance. Thus, for global range, the study showed that a certain glider design with low L/D would require only about three percent higher launch velocity than a design with L/D four times higher."

A technical debate with Ames Laboratory, which focused on maximizing L/D ratio, led to a compromise. Langley's smaller wing design with a high-lift, high-drag trajectory increased the glider's range from 4,700 to 5,600 nautical miles.

Becker's work highlighted the importance of balancing aerodynamic efficiency with thermal protection. In 1957, as Sputnik launched, NACA held its last major conference on high-speed aerodynamics. Cones, lifting bodies, and gliders became differentiated opinions. Becker's paper, "Preliminary Studies of Manned Satellites, Winged Configurations", dissenting from the consensus favoring ballistic projectiles, presented a vision for a winged, hypersonic vehicle capable of precise reentry and landing, influencing future aerospace innovations. "According to Becker, this paper...created more industry reaction- "almost all of it favorable" -than any other he had written."

Were it not for Sputnik and consensus toward a ballistic projectile, "Becker today believes, "the first U.S. manned satellite might well have been a [one-man] landable winged vehicle," a miniature (3000-pound) version of the later (180,000-pound) space shuttle."

National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), "Engineer in Charge," Detailed report on Project HYWARDS, including technical details on centrifugal lift, aerodynamic heating, collaborative efforts between NACA Langley and Ames Laboratories, and John V. Becker's contributions. Published in 1986, all of the information contained herein has been in the public domain for 38 years.

Available at:

The image used in this document is sourced from the NACA archives, depicting early hypersonic glider testing in a wind tunnel. Available at: https://picryl.com/media/high-lift-...he-10x10-foot-wind-tunnel-test-section-6eaaae.