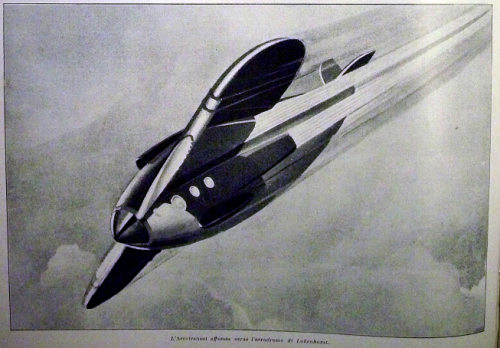

... mixed-powered future light transport airplane of 1931,it had a piston and rocket engines ... designer was De Bernardi,which developed this real aircraft...

We've got a number of problems here ...

First,

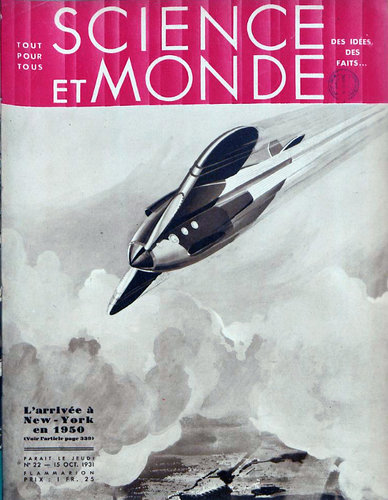

not a "real aircraft" design at all. This is an imaginary account of a transatlantic flight in an airliner of the 1950s written in 1931 by "

Ingénieur aéronautique", Jean Labadié for

Science et Monde. A full-sized airliner is implied ... so, not a "light transport" either.

De Bernardi

wasn't the "designer". At the end of the

l'Ala d'Italia article, it says "

Traduzione da "Science et Monde" ed adatiamento di J. da B. P.". That '

adatiamento' explains substituting Italian locations and personalities. So, instead of Paris-to-NY, its "Roma-New York". On take-off, the writer imagines himself sitting beside "pilota De Bernardi, ingegnere brevettato alla scuola Aeropolitecnica di Roma". But, of course Mario de Bernardi couldn't possibly teach at the Aeropolitecnica di Roma - no such school ever existed. The article simply translates the imaginary l'Ecole AéroPolytechnique and inserts the name of a famous Italian aviator (no French pilot is ever named in the original article).

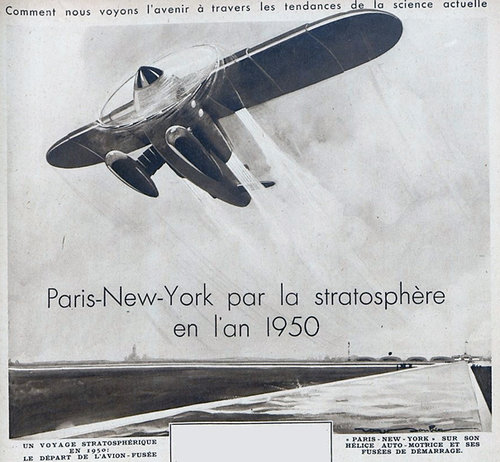

Labadié's description of the powerplant is quite fanciful and a bit vague. But neither a piston engine nor rocket motors are mentioned. Terms like "

aerobus-razzo" and "

aer-razzo" translate as '

x-rocket' today but, at the time, so did any type of 'reaction motor'. What the article is describing is some form of hybrid drive which can drive a propeller or use direct jet exhaust depending upon which is most efficient. The author says that the propeller acts as its own turbine motor. This occurs, he says, by venting hot gases through the hollow propeller blades. The prop would be used for take-off and then stopped in flight (presumably aligned with the wing to reduce drag). The gas from the reaction motors would then be vented directly to propel the aircraft at high altitude (~25,000 m being given as an optimal operational altitude for the jet engine).

In Italian introduction, the editor (or translator?) drops names of those working on concepts for ultra-fast, high-altitude transport in 1930-1931. These include De Grisogono and (Cosimo) Canovetti in Italy, Breguet, Michelin, and Bleriot in France, and Junkers in Germany. Labadié says that Junkers, Magni (Piero Magni/Magni Aviazione), and Esnault-Pelterie (R.E.P.) were then working on postal applications for reaction engines.

BTW: "Aerotransat" looks like the name of the craft in the Italian caption. Actually, Labadié gave his 1950s airline the name 'AéroTransat'.[/U]