Its funny how I can agree with everything here but disagree on the f-2, everything that wint wrong with that program happened in Japan. What design work happened in the us was done under GD and very little of that made it into the airframe, when Japan desired to widen the airframe to better fit there new radar they basically had to redesign the aircraft from the ground up. The us wanted a 400 foot^2 wing with a regular steel wing box and the base radar ( the f-16 couldn't handle the asea into the block 70 i think) not what Japan wanted, and all the issues the plane had was from Japan new tech. Then again that probably gave Japan more experience building planes then the f-15j upgrade would have (sense that was gust a tech upgrade with no structure changes).

Troubled Partnership. A History of U.S.-Japan Collaboration on the

For various reasons, the United States has generally tried to discourage its allies from developing their own major weapon sys- tems. Perhaps the most prominent example of this policy was Americas insistence on cooperative development in the case of Japans FS-X fighter aircraft. Did the...

apps.dtic.mil

The study group also stressed their claim that a domestic fighter would cost considerably less than a collaboration program, in complete opposition to American expert opinion. They repeated the same unit-production cost estimate used in the original mid-1985 TRDI study of ¥5 to 6 billion (excluding R&D costs), or only about half of the current cost oflicense-producing the F-15J.

Following the October briefings in Tokyo, American government and industry officials had to regroup and decide how to continue the effort in the face of the new information the Japanese provided. The need for political intervention had become increasingly evident. Most DoD officials agreed with the U.S. reporter who characterized the JDA as having "all but dismissed" the U.S. contractor proposals (Lachica, 1987a). The Japanese had made two fundamental points clear: (1) None of the U.S. contractor proposals fully met the FS-X operational requirements as first revealed in the October briefings, and (2) Japanese technology and subsystem development for an indigenous fighter were in advanced stages of development and could not be dropped or discarded. For the immediate future, the U.S. side believed it was now confronted with two basic options: either focus on further delaying the final Japanese source selection decision beyond the currently planned December deadline, or push for a broad agreement in principle now on a collaborative modification program and work to influence the content and details of such a collaboration later (Button, 1989b, p. 9). The Americans chose the first option.

Indeed, in March, right before the scheduled contractor visits to Tokyo, the U.S. companies mobilized their heavy political guns against the Japanese. Led by Senator Danforth, Congress increased pressure on the Reagan administration to press for an American-based FS-X. Senator Danforth wrote letters to the President, Secretary Weinberger, and Secretary of State Schultz warning that the adverse reaction to a decision in favor of indigenous development could damage U.S.-Japan relations. He argued that purchase of a U.S. fighter was necessary to help reduce the trade deficit and predicted a resurgence of protectionist sentiment in Congress if the Japanese persisted with their domestic program. As he told reporters in midmonth (Lachica, 1987a),

There's no excuse for Japan producing the airplane all by itself, not with a $60 billion trade surplus over the U.S. . . . This is one time the Japanese can't tell us that our products aren't good enough, or that they don't need what we make.

Japanese industry had been forced by U.S. political pressure and domestic budgetary realities to progressively retreat from each of its preferred positions, starting with domestic development, followed by codevelopment of a new design, then cooperative development of a radically modified U.S. fighter (SX-4, Super Hornet Plus), and ending with the SX-3 Upgrade.

FS-X was basically a revenge plot because of US trade deficits to Japan and an apparent one sided F-15 license agreement. FS-X was fundamentally a program to secure US jobs and interests in foreign aerospace industry rather than building Japan a new fighter.During the crucial negotiations in 1988, and even more so during the public controversy over FS-X that broke out in Congress in 1989, the U.S. government failed to develop a single, coordinated strategy toward the FS-X program that harmonized U.S. security and economic interests. Various elements within the U.S. government pressed differing agendas for the program, which often conflicted with each other. The Japanese side did not suffer from this problem. As one writer has pointed out, the Japanese working-level officials who negotiated the FS-X R&D MoU represented "the heart of the domestic development alliance: the Air Staff Office, TRDI and the [JDA] Equipment Bureau," supported by MITI (Noble, n.d., p. 20).

That isn't to say Japan is entirely fault free. There is mention that Japan went for the F-16 over the F-15 as it would never properly replace the F-4EJ and F-15 in Japanese service allowing for an actual proper domestic development down the line. This seems to be the case since F-X was planned from the get-go to replace the F-2 while the F-15 despite being older will remain in service. But with stuff like a massive increase in production costs for the program because US companies refused to match Japanese scale of production after a reduced procurement post cold war, it's really no different than the other examples provided.

The paper seems to agree that Japan was fully capable of producing it's own domestic fighter at the time. Even if the program wasn't even close to the "Half of F-15J license production" claim its still a much better than the F-2 because Japan wouldn't be actively trying to replace such a fighter only after 3 decades after introduction.

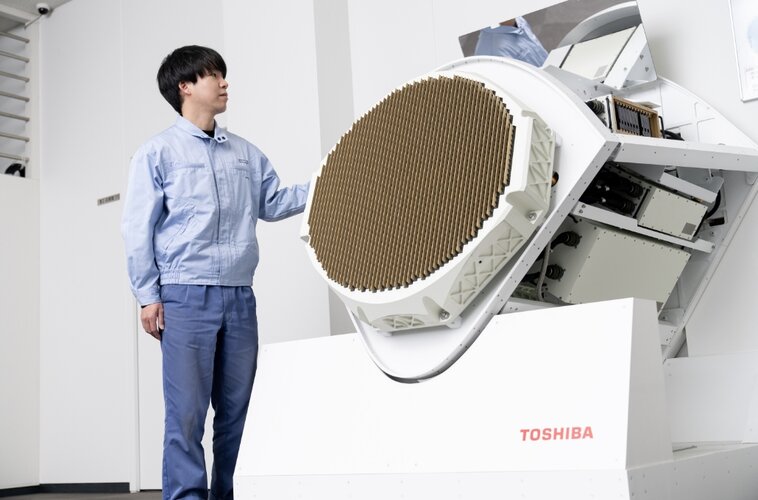

Joint collaboration on FS-X was objectively a failure in it's on paper function. It was there because Japan was seen as incapable of building an effective domestic fighter within a reasonable budget. The biggest criticisms from The Sullivan Visit shows a primary weariness in Japan's radar and composite air frame production capabilities because Japan refused to show the full capabilities of it's production lines and was used to discount domestic production. FFW to the F-2 and those are the 2 things Japan seemingly excelled at into world class status. If they left Japan to it's own devices the worst case scenario is you have an overbudget program with a limited production run exactly like the F-2, but this time it actually meets Japan's initial requirements. So wcs it's just a superior F-2 in terms of project goals.